A Roll of the Scottish Parliament, 1344 Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Set of Board Papers

Assynt House Beechwood Park Inverness, IV2 3BW Telephone: 01463 717123 Fax: 01463 235189 Textphone users can contact us via Date of Issue: Typetalk: Tel 0800 959598 23 November 2012 www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk HIGHLAND NHS BOARD MEETING OF BOARD Tuesday 4 December 2012 at 8.30 am Board Room, Assynt House, Beechwood Park, Inverness AGENDA 1 Apologies 1.1 Declarations of Interest – Members are asked to consider whether they have an interest to declare in relation to any item on the agenda for this meeting. Any Member making a declaration of interest should indicate whether it is a financial or non-financial interest and include some information on the nature of the interest. Advice may be sought from the Board Secretary’s Office prior to the meeting taking place. 2 Minutes of Meetings of 2 October and 6 November 2012 and Action Plan (attached) (PP 1 – 24) The Board is asked to approve the Minute. 2.1 Matters Arising 3 PART 1 – REPORTS BY GOVERNANCE COMMITTEES 3.1 Argyll & Bute CHP Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 31 October 2012 (attached) (PP 25 – 40) 3.2 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee Assurance Report of 1 November 2012 (attached) (PP 41 – 54) 3.3 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee – Terms of Reference for approval by the Board (attached) (PP 55 – 58) 3.4 Clinical Governance Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting of 13 November 2012 (attached) (PP 59 – 68) 3.5 Improvement Committee Assurance Report of 5 November 2012 and Balanced Scorecard (attached) (PP 69 – 80) 3.6 Area Clinical Forum – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 27 September 2012 (attached) (PP 81 – 88) 3.7 Asset Management Group – Draft Minutes of Meetings of 18 September and 23 October 2012 (attached) (PP 89 – 96) 3.8 Pharmacy Practices Committee (a) Minute of Meeting of 12 September 2012 – Gaelpharm Limited (attached) (PP 97 – 118) (b) Minute of Meeting of 30 October 2012 – Mitchells Chemist Limited (attached) (PP 119 – 134) The Board is asked to: (a) Note the Minutes. -

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 22 : Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 22: Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition January, 2012 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own communi- ty. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. Gaelic once was the dominant means of conversation in East Sutherland and the western districts of Caithness. Since the end of the 19 th century the language was on a relentless decline caused both by offi- cial ignorance and the low self-confidence of its speakers. A century later Gaelic is only spoken by a very tiny minority of inhabitants, most of them born well before the Second World War. Signs for the future still look not promising. Gaelic is still being sidelined officially in the whole area. Local council- lors even object to bilingual road-signs. Educational provision is either derisory or non-existent. Only constant parental pressure has achieved the introduction of Gaelic medium provision in Thurso and Bonar Bridge. -

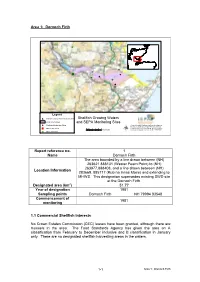

Area 1: Dornoch Firth Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites Report Reference No. 1 Name Dornoch Firth Location

Area 1: Dornoch Firth ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ! ^_ # ^_ # ^_ ^_ Legend # Shellfish Growing Waters Monitoring Sites Shellfish Growing Waters Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites ! Shellfish Production Sites (c) 2004 Scottish Environment Protection Agency. Includes material based upon Ordnance Survey " Marine Fish Farms 00.51 2 3 4 5 mapping with permission of H.M. Stationery Office. Kilometers (c) Crown Copyright. Licence number 100020538. ^_ Major Discharges µ Report reference no. 1 Name Dornoch Firth The area bounded by a line drawn between (NH) 263621 888131 (Wester Fearn Point) to (NH) 263977,888408, and a line drawn between (NH) Location Information 283669, 885717 (Rub na Innse Moire) and extending to MHWS. This designation supersedes existing SWD site at the Dornoch Firth. Designated area (km2) 51.77 Year of designation 1981 Sampling points Dornoch Firth NH 79994 83548 Commencement of 1981 monitoring 1.1 Commercial Shellfish Interests No Crown Estates Commission (CEC) leases have been granted, although there are mussels in the area. The Food Standards Agency has given the area an A classification from February to December inclusive and B classification in January only. There are no designated shellfish harvesting areas in the waters. 1- 1 Area 1: Dornoch Firth 1.2 Bathymetric Information This shellfish water encompasses almost the entire area of the Dornoch Firth. The area is some 22 km long by a maximum of 5.5 km wide. The maximum charted depth (at LAT) is <10 m. Approximately half of the area is <0 m chart depth, ie intertidal area exposed at low tide. -

Highland Primary Care Nhs Trust

PHARMACY PRACTICES COMMITTEE MEETING Tuesday, 30 October, 2012 at 1.30 pm Seminar Room, Migdale Hospital, Cherry Grove, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3ER Application by Gareth Dixon of MITCHELLS CHEMIST LTD for the provision of general pharmaceutical services at The Former Bonar Bridge News, Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3EB PRESENT Okain Maclennan (Chair) Margaret Thomson (Lay Member) Michael Roberts (Lay member) Susan Taylor (GP Sub Committee Nominate) Fiona Thomson (APC Non Contractor Nominate) John McNulty (APC Contractor Nominate) In Attendance Andrew J Green (Area Regulations, Contracts & Controlled Drugs Governance Pharmacist) Helen M MacDonald (Community Pharmacy Business Manager) Gareth Dixon, Mitchells Chemist Ltd, Applicant Donna Gillespie, Mitchells Chemist Ltd, Applicant Support Christopher Mair, GP Sub Committee Andrew Paterson, Area Pharmaceutical Committee Observers Nicola Macdonald (APC Contractor Nominate NHS Highland PPC Member in training) 1. The Chair welcomed everyone to Bonar Bridge. He asked all members to confirm that they had all received the papers for the hearing and had read and considered them. All members affirmed these points. 2. APPLICATION FOR INCLUSION IN THE BOARD’S PHARMACEUTICAL LIST Case No: PPC – Bonar Bridge, Sutherland. Mitchells Chemist Ltd, The former Bonar Bridge News, Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3EB. The Chair asked each Committee member if there were any interests to declare in relation to the application being heard from Mitchells Chemist Ltd. No interests were declared. 3. The Committee was asked to consider the application submitted by Mitchells Chemist Ltd to provide general pharmaceutical services from premises sited at The former Bonar Bridge News, Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3EB under Regulation 5(10) of the National Health Service (Pharmaceutical Services) (Scotland) Regulations 2009, as amended. -

2014 2 Friendly Companion January 2014

TThhee Friendly Companion Friendly Companion “The L ORD hath made all things for Himself.” (Proverbs 16. 4.) January 2014 2 Friendly Companion January 2014 Editor: Mr. G.D. Buss, “Bethany,” 7 Laines Head, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN15 1PH. Tel: 01249 656910. Email: [email protected] All correspondence (except that which relates to subscriptions) to be sent to the Editor. Annual Subscriptions inc. postage: U.K. U.S.A. & Canada Australia Europe (Netherlands) £13.50 $36 A$38 €25.00 All correspondence concerning subscriptions should be addressed to Mr. D. Christian, 5, Roundwood Gardens, Harpenden, Herts. AL5 3AJ. Cheques should be made out to Gospel Standard Publications. For United States and Canada, please send to Mr. G. Tenbroeke, 1725 Plainwood Drive, Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081, USA. Volume 140 January 2014 CONTENTS Our Monthly Message 3 Our Front Cover Picture 4 Good Wishes 5 For The Very Little Ones: Naomi Returns 6 Colouring Text: Ruth 1. 22. 7 Bible Lessons: The Burial Of Jesus 8 Three ‘B’s For 2014 10 A Dark Episode 12 Naaman 17 Sin 17 The Necessity Of Divine Life 18 Editor’s Postbag 18 Fascinating Flowerpots 19 Bible Study For The Older Ones: Light And Darkness (I) 20 Bible Questions: Washing And Making Clean 22 Poetry: A Conversation Between Two Brothers 24 Friendly Companion January 2014 3 OUR MONTHLY MESSAGE Dear Children and Young People, As you pick up the Friendly Companion this month it will be to read the first issue of another year. How quickly, to those of us who are older, do the years fly past! When you are younger, often time seems to drag, and there is a danger that you might wish your time away faster than God intends. -

1 COUNTYOFNEWYORK . in the Matter of Proving the Last Will And

1 COUNTY OF NEW YORK. In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and Testament of J ~ / Amended and Supplemental ANDREW CARNEGIE ( Notice of Probate. Deceased, > | Sec. 2616. And a Codicil thereto as a Will and Codicil of Real and\ ^ Personal Property. TO THE FOLLOWING NAMED PERSONS: TAKE NOTICE that the last will and testament of Andrew Carnegie, late of the County of New York, State of New York, deceased, has been offered for probate, and that the names and post-office addresses of the proponent and of the legatees, devisees and other beneficiaries, as set forth in the petition herein, who have not been cited or have not appeared or waived citation, are as follows: Home Trust Company, the proponent, whose post-office address is 51 Newark Street, Hoboken, New Jersey. Name of Legatee, Devisee or Beneficiary Post-Office Address Mrs. Leander M. Morris Oakmont, Allegheny County, Pa. Miss Cora B. Morris, 231 Hulton Road Oakmont, Allegheny County, Pa. Miss Mary B. Morris, 231 Hulton Road Oakmont, Allegheny County, Pa. Mrs. Thetta Quay Franks 135 East 66th Street, New York City. Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Cooper Square, cor. Third Aye,, New York. University of Pittsburgh , State Hall, Grant Boulevard, Pitts• burgh, Pa. Authors' Club, New York Carnegie Hall, New York City. Hampton Normal & Agricultural Institute Hampton, Virginia. Stevens Institute of Technology Castle Point, Hoboken, N. J. St. Andrews Society of the State of New York New York City. George Irvine - Fairfaaven, Watson Street,Baucbory, Kincardineshire, Scotland. Mrs. Eliza S. Nicoll InVerkip, Renfrewshire, Scotland. Miss Margaret Anderson 3.Roseburn Place, Murrayfield, Edin• burgh, Scotland. -

Cycle Routes Around Dornoch

Cycle Routes Around Dornoch quiet roads and glorious scenery Includes the Good Cycling Code his part of Sutherland was Spinningdale Mill T made for cycling – quiet (Route 5) roads, gentle gradients, and just so much to see. All our cycle routes start at the Tourist Information Centre in The Square, Dornoch, where you’ll find a vast amount of help, information, personal attention and local knowledge. Routes have been planned to avoid major roads and steep gradients wherever possible, whilst taking in the most spectacular scenery, historical sites and places where you’re most likely to see some of our more exotic Highland wildlife. Routes 1 and 2 take you past the fishing village of Embo to within sight of the old ferry port of Littleferry, visible across Loch Fleet, an internationally-renowned nature reserve where you can see an incredibly diverse range of ducks and waders. Route 3 extends the tour, beside the remains of the old “Dornoch Light Railway” line, along the edge of Loch Fleet to join the A9 at Cambusavie. Route 4 will show you the disused Dornoch Firth ferry terminal at Meikle Ferry, site of a great disaster in 1809 when 99 passengers were drowned in a storm. It took nearly 200 years to bridge the Firth here, although lighthouse designer George Stephenson drew up plans for a huge wooden bridge in 1831 which you can see in Dornoch’s “Historylinks” museum. Route 5 is for the energetic romantic, following the old A9 towards Bonar Bridge and ‘cutting the corner’ through Migdale’s “Fairy Glen,” an area of outstanding natural beauty. -

SUTHERLAND Reference to Parishes Caithness 1 Keay 6 J3 2 Thurso 7 Wick 3 Olrig 8 Waiter 4 Dunnet 9 Sauark 5 Canisbay ID Icajieran

CO = oS BRIDGE COUNTY GEOGRAPHIES -CD - ^ jSI ;co =" CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND Reference to Parishes Caithness 1 Keay 6 J3 2 Thurso 7 Wick 3 Olrig 8 Waiter 4 Dunnet 9 SaUark 5 Canisbay ID IcaJieran. Sutherland Durnesx 3 Tatujue 4 Ibrr 10 5 Xildsjnan 11 6 LoiK 12 CamJbriA.gt University fi PHYSICAL MAP OF CAITHNESS & SUTHERLAND Statute Afiie* 6 Copyright George FkOip ,6 Soni ! CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, MANAGER LONDON : FETTER LANE, E.C. 4 NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN CO. BOMBAY | CALCUTTA !- MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD. MADRAS J TORONTO : THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TOKYO : MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND by H. F. CAMPBELL M.A., B.L., F.R.S.G.S. Advocate in Aberdeen With Maps, Diagrams, and Illustrations CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1920 Printed in Great Britain ly Turnbull &* Spears, Edinburgh CONTENTS CAITHNESS PACK 1. County and Shire. Origin and Administration of Caithness ...... i 2. General Characteristics .... 4 3. Size. Shape. Boundaries. Surface . 7 4. Watershed. Rivers. Lakes . 10 5. Geology and Soil . 12 6. Natural History 19 Coast Line 7. ....... 25 8. Coastal Gains and Losses. Lighthouses . 27 9. Climate and Weather . 29 10. The People Race, Language, Population . 33 11. Agriculture 39 12. Fishing and other Industries .... 42 13. Shipping and Trade ..... 44 14. History of the County . 46 15. Antiquities . 52 1 6. Architecture (a) Ecclesiastical . 61 17. Architecture (6) Military, Municipal, Domestic 62 1 8. Communications . 67 19. Roll of Honour 69 20. Chief Towns and Villages of Caithness . 73 vi CONTENTS SUTHERLAND PAGE 1. -

Creich Community Council

Minutes approved 21/03/2017 CREICH COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday 21st March 2017 at 7.30pm in Invershin Hall Present: Pete Campbell, Chair (PC), Ron Boothroyd, Vice Chair (RB), Russell Taylor, Treasurer (RT), Norman MacDonald (NM), Russell Smith (RS), John White (JW) Apologies: Brian Coghill (BC), Graham MacKenzie, Head of Roads Dept., THC (GM) Also present: Highland Councillor George Farlow (GF), Garry Cameron, Ward Manager THC, Christine Ross, VG-ES, Colin Gilmour (CG), Michael Baird (MB), Robert Howden Police Scotland: Sgt Peter Allan (PA) Secretary: Mary Goulder (MG) Item 1. Welcome/Apologies (as above). Chair Pete Campbell opened the meeting at 7.30pm, thanking Sgt Allan for attending and for his recent work regarding traffic/parking issues. Item 2. Police report/Police Scotland and Highland Council update re traffic/parking issues. Six incidents were noted in the monthly report, three were weather related, one road traffic accident, and two alarm calls which were also weather related. Eight incidents of speeding were recorded. PA indicated that speeding issues are a main focus for the Road Policing Department with numbers of reported cases on the increase. PA began his update with a further apology to the CC for the lack of response to its contacts and queries last year regarding the traffic/parking issues in Bonar Bridge and Spinningdale. Police Scotland has been experiencing major IT problems for some time, hopefully resolving. The issues raised did eventually come to the attention of the Area Commander, also Inspector Wilson and PA. He has worked on gathering information since then and has been in contact with THC through the Head of Roads Department, Graham MacKenzie and Joanna Sutherland. -

Region 3 North-East Scotland: Cape Wrath to St. Cyrus

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 3 North-east Scotland: Cape Wrath to St. Cyrus edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody & N.C. Davidson Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1996 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, J.C. Brooksbank, F.J. Wright Administration & editorial assistance C.A. Smith, R. Keddie, E. Leck, S. Palasiuk, J. Plaza, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice comes from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group Prof. S.J. Lockwood MAFF Directorate of Fisheries Research C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment and Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. Pullen WWF UK (Worldwide Fund for Nature) N. -

Do More Cycling

Do more cycling EIGHT CYCLE ROUTES AROUND dornoch cYcLe routeS Around dornoch route 1 Loch Fleet Distance: 12.5 miles Grade: Easy Description: Route 1 takes you past the fishing village of Embo and to Loch Fleet, an internationally-renowned nature reserve where you can see a range of ducks, seals and wading birds. Directions: Travel out of Dornoch on Station Road towards Embo. Continue on this road for 3 miles. Turn left and ride along the shores of Loch Fleet for 2 miles until you reach the junction with the A9. Turn around and follow the same route back into Dornoch. An alternative off-road section is indicated on the map, following the disused railway line. Family Friendly RETURN VIA THE SAME ROUTE DORNOCH FLEET LITTLE FERRY SKELBO A9 FOURPENNY EMBO POLES RETURN VIA THE SAME ROUTE A9 B9168 PITGRUDY A949 EVELIX MAIN ROUTE CAMORE START ALTERNATIVE DORNOCH route 2 Skelbo Street Distance: 8 miles Grade: Medium Description: Route 2 takes you past the fishing village of Embo and past Skelbo Forest. Directions: Travel out of Dornoch on Station Road for 2.8 miles (past Embo junction) until you see a sign on the left for Skelbo Forest Walk. Follow this route over a staggered junction into Skelbo Street, then past the forest walk entrance. Turn left onto the A9 for 0.5 mile then left onto the B9168 (Poles Road) for 2 miles. Turn left onto Castle Street and back into Dornoch town centre. (Alternative route avoiding most of the A9 – turn left at the staggered junction to come out at the Trentham Hotel and Poles Road). -

Seasonal Highlights Our Top Three Things to Try Wildlife

Seasonal highlights Wildlife Spring and summer Although tricky to spot, there is an abundance Get up with sunrise for a wander in the woods of wildlife living here. Their ‘chip chip’ call from and immerse yourself in bird song. A warm spring the pinewoods alerts you to a flock of crossbills. day will tease pine cones open with a crack. As Redstarts and tree pipits arrive in spring. the season progresses, orchids together with Dragonflies, damselflies and butterflies patrol tasty blaeberries emerge. Take a deep breath, the the air in the warm sunny days of spring and aromas of the woods shift subtly as the days pass. summer, elaborate There is something special about a pinewood in fungi emerge later spring. in the year. Autumn and winter After a long As summer retreats enjoy the red and gold leaves absence, red of the aspen and oak. As the leaf litter grows look squirrels are being for fungi pushing through before icy winds from reintroduced to the north bring snow. the woodland in autumn 2019. Our top three things to try Loch Migdale The loch view is a must-see for every visitor - from the shore, or from the bench higher up the hill. Spinningdale view One of the most northerly oakwoods in the UK, this slightly longer walk takes you on an adventure though the trees to a wonderful view over the old Spinningdale mill and beyond to the Dornoch Firth. Speckled Wood John Bridges/WTML Peregrine John MacPherson/WTML Natural wonders From the chatter of birds and the rustling of leaves, to the colours of lichen and the chance sighting of a butterfly, there is always something to encounter in this wood.