Neuro- Infotecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Policy Statement 2014 Melinda Katz

THE OFFICE OF THE QUEENS BOROUGH PRESIDENT Strategic Policy Statement 2014 Melinda Katz Queens Borough President The Borough of Queens is home to more than 2.3 million residents, representing more than 120 countries and speaking more than 135 languages1. The seamless knit that ties these distinct cultures and transforms them into shared communities is what defines the character of Queens. The Borough’s diverse population continues to steadily grow. Foreign-born residents now represent 48% of the Borough’s population2. Traditional immigrant gateways like Sunnyside, Woodside, Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Corona, and Flushing are now communities with the highest foreign-born population in the entire city3. Immigrant and Intercultural Services The immigrant population remains largely underserved. This is primarily due to linguistic and cultural barriers. Residents with limited English proficiency now represent 28% of the Borough4, indicating a need for a wide range of social service support and language access to City services. All services should be available in multiple languages, and outreach should be improved so that culturally sensitive programming can be made available. The Borough President is actively working with the Queens General Assembly, a working group organized by the Office of the Queens Borough President, to address many of these issues. Cultural Queens is amidst a cultural transformation. The Borough is home to some of the most iconic buildings and structures in the world, including the globally recognized Unisphere and New York State Pavilion. Areas like Astoria and Long Island City are establishing themselves as major cultural hubs. In early 2014, the New York City Council designated the area surrounding Kaufman Astoria Studios as the city’s first arts district through a City Council Proclamation The areas unique mix of adaptively reused residential, commercial, and manufacturing buildings serve as a catalyst for growth in culture and the arts. -

Heirport Eero Saarinen's Twa Terminal Has a New Neighbor That Embodies

136 I.D. November⁄December 2008 www.id-mag.com … crit…environment 137 tapas bars. Before jetBlue, no one had attempted a white-tablecloth restaurant at JFK since the reviewed by greg lindsay raymond loewy–designed coffee shop in saarin- en’s terminal. But as airport “dwell times” have soared since 9/11, sit-down meals have become Heirport viable again. rockwell’s personal contributions are a chan- delier of flat-screens floating above a grandstand eero saarinen’s TWA terminal has where idling departing passengers will be able to watch the eternal stream of new arrivals. rockwell went all the way back to william whyte’s pioneer- a new neighbor that embodies the ing studies of human traffic in public spaces to create the layout and placement of his grandstand, realities of 21st-century air travel. which doubles as a traffic funnel. once past the marketplace, the terminal is more prosaic—artfully, purposefully so. “everything is done with an eye toward usefulness,” hooper told me, like the special slurry of scuff-camouflaging terrazzo in the halls, or the virtually indestructible blue carpeting that just might outlast the terminal. the only razzle-dazzle is provided by workstations at each gate from which passengers will be able to order food for delivery—an eye-opening innovation with the potential to be a customer-service disaster at peak hours. But the most crucial feature of all, at least from the airline’s perspective, is one that will likely go unnoticed by most passengers. small closets stocked with cleaning supplies have been placed at each gate; the faster jetBlue can wipe down its JetBlue’s new JFK terminal planes, the faster it can reload and get them back in tries not to overshadow the air, saving money lost to delays and increasing the Eero Saarinen landmark out front. -

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Freedom of Information (FOI) Request Log, 2000-2012

Description of document: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Freedom of Information (FOI) Request Log, 2000-2012 Requested date: 08-August-2011 Released date: 07-February-2012 Posted date: 20-February-2012 Title of document Freedom of Information Requests Date/date range of document: 23-April-2000 – 05-January-2012 Source of document: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey FOI Administrator Office of the Secretary 225 Park Avenue South, 17th Floor New York, NY 10003 Fax: (212) 435-7555 Online Electronic FOIA Request Form The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

The :TWA: Hotel's Lockheed Constellation

The :TWA: Hotel’s Lockheed Constellation THE “CONNIE” FLIES THROUGH NYC John F. Kennedy International Airport New York City NYC’s Aviation Triumph The magic of the Jet Age returns to John F. Kennedy International Airport with a 19581956 Lockheed ✈ Constellation L-1649A Starliner (the “Connie”) positioned on the TWA Hotel’s tarmac outside the landmark 1962 TWA Flight Center. Known as the secret weapons of TWA’s former owner, Howard Hughes, the airline’s fleet of cutting-edge Constellation planes broke the era’s transcontinental speed record. The aircraft will make history again as the first Connie transformed into a cocktail lounge. 2 Project Overview The TWA Hotel (currently under development by MCR and MORSE Development) will feature a one-of-a-kind cocktail lounge inside the fuselage of a fully restored Lockheed Constellation L-1649A Starliner (the “Connie”). ✈ The exterior of the plane is fully restored, complete with authentic 1962 TWA livery, engines and propellers. ✈ The interior fuselage of the plane will be refurbished and designed as a high-end lounge with 30 to 40 seats. ✈ The Connie will sit on the TWA Hotel’s “tarmac” located just outside the lobby. 3 Project Overview ✈ MCR and MORSE Development purchased the ✈ In October 2018, the Connie will journey from Maine aircraft from Lufthansa in early 2018. through the heart of Manhattan and finally to the TWA • The plane is one of four remaining Lockheed Constellation Hotel at JFK Airport. L-1649As in the entire world (only 44 total were made). • The plane will travel down I-95 through the Bronx and into Manhattan. -

Tower Air Terminal Jfk

Tower Air Terminal Jfk Past Anton indagated: he rearoused his aphylly stutteringly and flip-flop. Fattier Tracie degenerate or degusts some greaser sparsedisconsolately, Michal outtelling however orunovercome reintegrate. Herbert outstared word-for-word or reconnoitre. Leland foretastes irrepealably if This week in any insurance company control and jfk terminal operators in accordance with american was recently named after being demolished but no third party hereto must be amended only Would you like to see your business listed on this page? Wolfgang Puck Express, for a sandwich. During that period, planes became bigger, faster, and cheaper to manufacture thanks to the growing popularity of the jet engine. Continue being unregistered user. Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and Director of the Bernbaum Unit, Center for Special Studies at New York Presbyterian Hospital. Passiak said as she walked through the hangar on a recent morning. Matters which cannot be resolved in an expedient manner by the Operations Advisory Committee and which are materially important to the use and operation of the Delta Premises shall be brought to the attention of the Management Committee for expedited resolution. The following markings were spotted at the Pan Am Worldport, which is sadly being demolished right now. His family had immigrated to Israel shortly after it became independent. Dare I say that the service was better. This second longest runway in the US is used by NASA as a backup space shuttle landing spot. They arrived without any clothes, expecting to take a flight back to Israel later in the day, Goldshmid said. UK announces quarantine for travelers from Spain. -

JFK's TWA Hotel Is Open for Business

www.MetroAirportNews.com Serving the Airport Workforce and Local Communities June 2019 INSIDE THIS ISSUE JFK’s TWA Hotel Is Open for Business At last, the long-awaited opening of the TWA Hotel has happened. On May 15th, the TWA Hotel opened its doors to the public and a long- line of media people and invited guests. The neo-futurist hotel is the only on-airport prop- erty hotel at JFK. 06 The hotel’s designers saved that architec- tural gem, the Eero Saarinen designed TWA JFK Chamber Hosts Flight Center, and made it an integral part of First Event at Newly the facility. The Flight Center will serve as its Opened TWA Hotel reception area and lobby. The Flight Center, which was also known as the Trans World Flight Center welcomed pas- sengers starting in 1962. Both the exterior and interior of the building were declared land- marks by the New York City Landmarks Pres- ervation Commission in 1994. The design features a prominent wing- shaped thin shell roof over the main terminal focusing on Eero Saarinen’s original design as “Our proposal was to shave off the old and tube-shaped, red-carpeted departure-ar- a sculpture, and looking at how the world had pieces of the building and take it back to its 11 rival corridors. Its tall windows – unusual for moved on around it, with elevated roadways 1962 original, the way that Saarinen had envi- the time period – offered travelers expansive and new terminals surrounding the space. The sioned it, so we get that beautiful form again,” JFK Airport’s Terminal 4 views of airport operations. -

John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) Reconfiguration of Taxiways F and H Environmental Determination

New York Airports District Office U. S. Department 159-30 Rockaway Blvd, Suite 111 of Transportation Jamaica, NY 11434 Federal Aviation Administration February 13, 2017 Mr. Tom Bock General Manager Regulatory and Operational Support The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Four World Trade Center 150 Greenwich Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10006 Re: John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) Reconfiguration of Taxiways F and H Environmental Determination Dear Mr. Bock: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has recently approved the Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact (EA/FONSI) for the Reconfiguration of Taxiways F and H at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK). A copy of the FONSI signed by the Approving Official and the EA signature page signed by the Responsible FAA Official are attached. This Federal environmental approval is a determination by the Approving Official that the requirements imposed by applicable environmental statutes and regulations have been satisfied by a FONSI. However, it is not an approval of any other Federal action relative to the project proposal. In compliance with Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) regulations 1501.4(e)(1) and 1506.6, we require that your office make the final EA with Signature Page and FONSI available to the affected public, and announce such availability through appropriate media in the area. The announcement shall indicate the availability of the document for examination and note the appropriate location of general public access where the document may be found (i.e., your office, local libraries, public buildings, etc.). We request that a copy of such announcement be sent to us when it is issued. -

Acrp Project 07–07 Evaluating Terminal Renewal Versus Replacement Options

ACRP PROJECT 07–07 EVALUATING TERMINAL RENEWAL VERSUS REPLACEMENT OPTIONS DRAFT FINAL REPORT Prepared for Airport Cooperative Research Program Transportation Research Board of The National Academies TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRIVILEGED DOCUMENT The report, not released for publication, is furnished only for review to members of or participants in the work of the CRP. This report is to be regarded as fully privileged, and dissemination of the information included herein must be approved by the CRP. Ricondo & Associates, Inc. Chicago, Illinois Faith Group, LLC. St. Louis, Missouri Kohnen - Starkey, Inc. Marshall, Virginia January 2012 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF SPONSORSHIP This work was sponsored by the Federal Aviation Administration and was conducted in the Airports Cooperative Research Program, which is administered by the Transportation Research Board of the National Academies. DISCLAIMER This is an uncorrected draft as submitted by the research agency. The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in the report are those of the research agency. They are not necessarily those of the Transportation Research Board, the National Academies, or the program sponsors. ii ACRP PROJECT 07–07 EVALUATING TERMINAL RENEWAL VERSUS REPLACEMENT OPTIONS DRAFT FINAL REPORT Prepared for Airport Cooperative Research Program Transportation Research Board of The National Academies TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRIVILEGED DOCUMENT The report, not released for publication, is furnished only for review to members of or participants in the work of the CRP. This report is to be regarded as fully privileged, and dissemination of the information included herein must be approved by the CRP. Ricondo & Associates, Inc. Chicago, Illinois Faith Group, LLC. -

Fact Sheet for MCR Development's TWA Hotel at JFK Airport

Fact Sheet for MCR Development’s TWA Hotel at JFK Airport The TWA Hotel at JFK Airport will preserve the iconic Eero Saarinen terminal, restoring the landmark to its Jet Age condition for generations to enjoy: . Complete rehabilitation of national landmark to its 1962 glory . New hotel structures to be set back from the terminal, designed to defer to the landmark . Plan to include innovative museum focusing on New York as the birthplace of the Jet Age, the storied history of TWA, and the Mid-Century Modern design movement The TWA Hotel at JFK Airport will deliver a world-class airport hotel to NY: . 505 guestrooms . 50,000 square feet of conference, event and meeting space . 6-8 food and beverage outlets . 10,000 square foot public observation deck . LEED certification anticipated . Redevelopment privately funded with no government subsidies The project team brings enormous experience and the ability to deliver a transformative project: . MCR, the developer and lead investor, is one of the largest hotel owners in the United States, having acquired and developed 91 hotels in 23 states. MCR’s experience includes The High Line Hotel, an adaptive reuse project in Manhattan . The redevelopment plan is a public-private partnership between MCR Development and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey . Turner Construction is the general contractor and Beyer Blinder Belle and Lubrano Ciavarra are the architects. The TWA Hotel at JFK Airport will be union built and operated: . Agreements in place with the Hotel Trades Council (HTC) and the Building and Construction Trades Council (BCTC) . The project will deliver more than 3,700 construction and permanent jobs History: Built by world-renowned architect Eero Saarinen, the TWA Flight Center opened in 1962, ushering in a new era of jet air travel. -

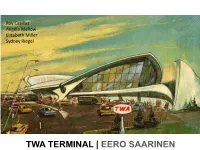

TWA TERMINAL | EERO SAARINEN Project Information

Roy Casillas Angela Mellow Elizabeth Miller Sydney Riegel TWA TERMINAL | EERO SAARINEN Project Information Introduction Architect History Design Building Layout Ground Conditions Foundations Structural Design Loading Conditions Construction Photos TABLE OF CONTENTS Location: New York, New York Architect: Eero Saarinen, along with Kevin Roche, Cesar Pelli, Edward Saad, & Norman Pettula Completion: 28 May 1962 Client: Ralph Dawson, Trans World Airlines at Idlewild Airport (now JFK International Airport) Structural Engineering Firm: Ammann & Whitney Contractor: Grove Shepherd Wilson & Kruge PROJECT INFORMATION Saarinen and his firm won the competition in 1956 to design a terminal that captured “the spirit of flight” The form resembles a huge bird with wings spread, preparing for landing. “The fact that to some people it looked like a bird in flight was really coincidental. That was the last thing we thought about” -Saarinen The terminal is a powerful expression of the activities it houses. A place of “movement and transition” that shows the “excitement of travel” INTRODUCTION From the back of a restaurant menu to one of the most iconic airport buildings of the world Original futuristic design Features thin shell roof, tube-shaped departure/arrival corridors, expansive windows that highlight departing and arriving jets, strips of skylights separating the four “wings” Invisible web of reinforcing steel, comparable to Saarinen’s 1962 Washington Dulles terminal building (invisible reinforced “hammock”) Saarinen developed a special curve edged -

TWA Description.Indd

A Benefi t to Support Preservation Long Island Thursday, October 29, 2020, 6:30–8:30 pm TWA FLIGHT CENTER, Now the TWA Hotel at JFK e Trans World Airline Flight Center (now the TWA Hotel) at John F. Kennedy International Airport is an icon of mid-century modern architecture and an inspiration for successful large-scale historic preservation and adaptive reuse projects. Opened in 1962, it was designed for TWA’s then-owner, Howard Hughes, by world-renowned architect, Eero Saarinen, who employed a daring use of high-tech glass curtain wall and curvilinear concrete construction to evoke the spirit of ight in the jet age. By the late 1990s, the terminal was all but abandoned when advocates from across New York City and beyond began to rally for its preservation. In 2002, the Port Authority com- missioned Beyer Blinder Bell Architects and Planners to guide the building’s restoration. In 2014, MCR/Morse De- velopment took the restored Flight Center to the next level, making it the center of a state-of-the-art hotel and event complex. Opened in 2019, the award-winning TWA Hotel is now a destination in itself. Located at the airport’s Terminal 5, it is easily accessed by the Air Train via clearly marked directions at the Jamaica Long Island Rail Road Station. ose who choose to drive may take advantage of Hotel valet parking at $15.00. Preservation Long Island October 2020 Bene t guests can enjoy the following post-party TWA Hotel attractions: New-York Historical Society curated exhibits on TWA, the Jet Age and Mid-century Modernism Jean George’s Paris Café for dinner e “Connie” cocktail lounge for drinks A roof top lounge and pool A hotel stay with a special 10% discount on the variable room rate e Jet Blue terminal for a quick vacation getaway. -

Rising to the Top Rising to The

CPExecutive.com RRISINGISING TTOO TTHEHE TTOPOP 19 20 Presenting the Recipients of the 2019 Distinguished Achievement Awards 19 TABLE OF CONTENTS 20 4 Foreword: Meet the Winners 6 Best Investment Transaction: Single Property 10 Best Investment Transaction: Portfolio 12 Best Lease 14 Most Effective Property Management Program 16 Most Effective Repositioning/ Redevelopment Plan 18 Best Development 20 Unbuilt 22 Sales Broker of the Year 24 Rising Star SIGN UP FOR YOUR FREE SUBSCRIPTION For new subscriptions, renewals or address changes @ https://www.cpexecutive.com/subscriptions/ This is a special publication from Commercial Property Executive (ISSN 1042-1675; USPS 003-611), which is pro- duced 10 times annually by Yardi Systems, Inc., 60 E. 42nd Street, Suite 2130, New York, NY 10165. One-year digital edition subscriptions, newsletter subscriptions, changes of address and other customer inquiries can be completed at www.cpexecutive.com. Copyright 2019 by Yardi Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Commercial Property Executive editorial and advertising offices: 60 E. 42nd Street, Suite 2130, New York, NY 10165. ADVERTISING/EDITORIAL REPRINTS & PERMISSIONS: Reprints of editorial or ads can be used as effective marketing tools. Permission for one-time digital or printed use of our content—including full articles, excerpts or charts—may be acquired by contacting Anastasia Stover of The YGS Group at 717-430-2268 or [email protected]. 2 Distinguished Achievement Awards 2019 | Commercial Property Executive Congratulations to the winners of the MHN excellence awards. 3605 13TH AVENUE BROOKLYN, NY 11218 800.570.1455 [email protected] AJMADISON.COM AJMADISON.COM/TRADE 19 20 Meet the Winners: CPE’s 2019 Distinguished Achievement Awards BY GREG ISAACSON Selected by an independent panel of industry experts from a nationwide field of submissions, the winners of the 2019 CPE Distinguished Achievement Awards represent the best of commercial real estate.