NASA: Actions Needed to Improve the Management of Human Spaceflight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

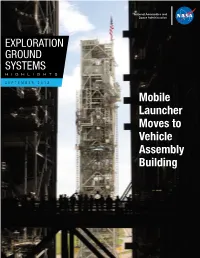

Mobile Launcher Moves to Vehicle Assembly Building EGS MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS

National Aeronautics and Space Administration EXPLORATION GROUND SYSTEMS HIGHLIGHTS SEPTEMBER 2018 Mobile Launcher Moves to Vehicle Assembly Building EGS MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS 3 Mobile launcher on the move 4 In the driver’s seat 5 Prepping for Underway Recovery Test 7 6 Employees, guests view ML move MOBILE LAUNCHER ON THE MOVE NASA’s mobile launcher is inside High Bay 3 at the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on Sept. 11, 2018, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Photo credit: NASA/Frank Michaux NASA’s mobile launcher, atop crawler-transporter 2, traveled from Launch Pad 39B to the Vehicle Assembly Building at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, on Sept. 7, 2018. Arriving late in the afternoon, the mobile launcher stopped at the entrance to the VAB. Early the next day, Sept. 8, engineers and technicians rotated and extended the crew access arm near the top of the mobile launcher tower. Then the mobile launcher was moved inside High Bay 3, where it will spend about seven months undergoing verification and validation testing with the 10 levels of new work platforms, ensuring that it can provide support to the agency’s Space Launch System (SLS). The 380-foot-tall structure is equipped with the crew access Cliff Lanham, NASA project manager for the mobile launcher, takes a break arm and several umbilicals that will provide power, environmental to attend the employee event for the mobile launcher move to the Vehicle control, pneumatics, communication and electrical connections Assembly Building on Sept. 7, 2018, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. -

ORION ORION a to Z APOGEE to Break the Frangible Joints and Separate the Fairings, Three Parachutes

National Aeronautics and Space Administration ORION www.nasa.gov ORION A to Z APOGEE to break the frangible joints and separate the fairings, three parachutes. The next two parachutes will then VAN ALLEN RADIATION BELTS The term apogee refers to the point in an elliptical exposing the spacecraft to space. LAS - LAUNCH ABORT SYSTEM deploy and open. Once the spacecraft slows to around The Van Allen Belts are belts of plasma trapped by orbit when a spacecraft is farthest from the Earth. Orion’s Launch Abort System (LAS) is designed to 100 mph, the three main parachutes will then deploy the Earth’s magnetic field that shield the surface of During Exploration Flight Test-1, Orion’s flight path will GUPPY propel the crew module away from an emergency on using three pilot parachutes and slow the spacecraft the Earth from much of the radiation in space. During take it to an apogee of 3,600 miles. Just how high is The Super Guppy is a special airplane capable of the launch pad or during initial takeoff, moving the to around 20 mph for splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. Exploration Flight Test-1, Orion will pass within the Van that? A commercial airliner flies about 8 miles above transporting up to 26 tons in its cargo compartment crew away from danger. Orion’s LAS has three new When fully deployed, the canopies of three main Allen Radiation Belts and will spend more time in the the Earth’s surface, so Orion’s flight is 450 times farther measuring 25 feet tall, 25 feet wide, and 111 feet long. -

The Orbital-Hub: Low Cost Platform for Human Spaceflight After ISS

67th International Astronautical Congress (IAC), Guadalajara, Mexico, 26-30 September 2016. Copyright ©2016 by the International Astronautical Federation (IAF). All rights reserved. IAC-16, B3,1,9,x32622 The Orbital-Hub: Low Cost Platform for Human Spaceflight after ISS O. Romberga, D. Quantiusa, C. Philpota, S. Jahnkea, W. Seboldta, H. Dittusb, S. Baerwaldeb, H. Schlegelc, M. Goldd, G. Zamkad, R. da Costae, I. Retate, R. Wohlgemuthe, M. Langee a German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Space Systems, Bremen, Germany, [email protected] b German Aerospace Center (DLR), Executive Board, Space Research and Technology, Cologne, Germany, c European Space Agency (ESA) Contractor, Johnson Space Center, Houston, USA, d Bigelow Aerospace, Las Vegas / Washington, USA, e Airbus DS, Bremen, Germany Abstract The International Space Station ISS demonstrates long-term international cooperation between many partner governments as well as significant engineering and programmatic achievement mostly as a compromise of budget, politics, administration and technological feasibility. A paradigm shift to use the ISS more as an Earth observation platform and to more innovation and risk acceptance can be observed in the development of new markets by shifting responsibilities to private entities and broadening research disciplines, demanding faster access by users and including new launcher and experiment facilitator companies. A review of worldwide activities shows that all spacefaring nations are developing their individual programmes for the time after ISS. All partners are basically still interested in LEO and human spaceflight as discussed by the ISECG. ISS follow-on activities should comprise clear scientific and technological objectives combined with the long term view on space exploration. -

NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences and Research Applications

NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences and Research Applications SLSPRA has 11 topics listed below and on the following pages for your consideration and possible involvement. (1) Program: Physical Sciences Program (2) Research Title: Dusty Plasmas (3) Research Overview: Dusty plasma research uses dusty plasmas – mixtures of electrons, ions, and charged micron-size particles as a model system to understand astronomical phenomena involving dust-laden plasmas, and as a simplified system modelling the behavior of many-body systems in problems of statistical and condensed matter physics. Dusty plasma research also addresses practical questions of dust management in planetary exploration missions. Proposals are sought for research on dusty plasmas, particularly on the transport of particles in dusty plasmas. 4) NASA Contact a. Name: Bradley Carpenter, Ph.D. b. Organization: NASA Headquarters Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications (SLPSRA) c. Work Phone: (202) 358-0826 d. Email: [email protected] 5) Commercial Entity: a. Company Name: na b. Contact Name: na c. Work Phone: na d. Cell Phone: na e Email: na 6) Partner contribution No NASA Partner contributions 7) Intellectual property management: No NASA Partner intellectual property concerns 8) Additional Information: All publications that result from an awarded EPSCOR study shall acknowledge NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications (SLPSRA). NNH20ZHA001C NASA EPSCoR Rapid Response Research (R3) NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences and Research Applications (continued) 1) Program: Fluids Physics and Combustion Science 2) Research Title: Drop Tower Studies 3) Research Overview: Fundamental discoveries made by NASA researchers over the last 50 years in fluids physics and combustion have helped enable advances in fluids management on spacecraft water recovery and thermal management systems, spacecraft fire safety, and fundamental combustion and fluids physics including low-temperature hydrocarbon oxidation, soot formation and flame stability. -

Race to Space Educator Edition

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grade Level RACE TO SPACE 10-11 Key Topic Instructional Objectives U.S. space efforts from Students will 1957 - 1969 • analyze primary and secondary source documents to be used as Degree of Difficulty supporting evidence; Moderate • incorporate outside information (information learned in the study of the course) as additional support; and Teacher Prep Time • write a well-developed argument that answers the document-based 2 hours essay question regarding the analogy between the Race to Space and the Cold War. Problem Duration 60 minutes: Degree of Difficulty -15 minute document analysis For the average AP US History student the problem may be at a moderate - 45 minute essay writing difficulty level. -------------------------------- Background AP Course Topics This problem is part of a series of Social Studies problems celebrating the - The United States and contributions of NASA’s Apollo Program. the Early Cold War - The 1950’s On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy spoke before a special joint - The Turbulent 1960’s session of Congress and challenged the country to safely send and return an American to the Moon before the end of the decade. President NCSS Social Studies Kennedy’s vision for the three-year old National Aeronautics and Space Standards Administration (NASA) motivated the United States to develop enormous - Time, Continuity technological capabilities and inspired the nation to reach new heights. and Change Eight years after Kennedy’s speech, NASA’s Apollo program successfully - People, Places and met the president’s challenge. On July 20, 1969, the world witnessed one of Environments the most astounding technological achievements in the 20th century. -

Mars, the Nearest Habitable World – a Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration

Mars, the Nearest Habitable World – A Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration Report by the NASA Mars Architecture Strategy Working Group (MASWG) November 2020 Front Cover: Artist Concepts Top (Artist concepts, left to right): Early Mars1; Molecules in Space2; Astronaut and Rover on Mars1; Exo-Planet System1. Bottom: Pillinger Point, Endeavour Crater, as imaged by the Opportunity rover1. Credits: 1NASA; 2Discovery Magazine Citation: Mars Architecture Strategy Working Group (MASWG), Jakosky, B. M., et al. (2020). Mars, the Nearest Habitable World—A Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration. MASWG Members • Bruce Jakosky, University of Colorado (chair) • Richard Zurek, Mars Program Office, JPL (co-chair) • Shane Byrne, University of Arizona • Wendy Calvin, University of Nevada, Reno • Shannon Curry, University of California, Berkeley • Bethany Ehlmann, California Institute of Technology • Jennifer Eigenbrode, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center • Tori Hoehler, NASA/Ames Research Center • Briony Horgan, Purdue University • Scott Hubbard, Stanford University • Tom McCollom, University of Colorado • John Mustard, Brown University • Nathaniel Putzig, Planetary Science Institute • Michelle Rucker, NASA/JSC • Michael Wolff, Space Science Institute • Robin Wordsworth, Harvard University Ex Officio • Michael Meyer, NASA Headquarters ii Mars, the Nearest Habitable World October 2020 MASWG Table of Contents Mars, the Nearest Habitable World – A Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... -

L AUNCH SYSTEMS Databk7 Collected.Book Page 18 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM Databk7 Collected.Book Page 19 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM

databk7_collected.book Page 17 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM CHAPTER TWO L AUNCH SYSTEMS databk7_collected.book Page 18 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM databk7_collected.book Page 19 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM CHAPTER TWO L AUNCH SYSTEMS Introduction Launch systems provide access to space, necessary for the majority of NASA’s activities. During the decade from 1989–1998, NASA used two types of launch systems, one consisting of several families of expendable launch vehicles (ELV) and the second consisting of the world’s only partially reusable launch system—the Space Shuttle. A significant challenge NASA faced during the decade was the development of technologies needed to design and implement a new reusable launch system that would prove less expensive than the Shuttle. Although some attempts seemed promising, none succeeded. This chapter addresses most subjects relating to access to space and space transportation. It discusses and describes ELVs, the Space Shuttle in its launch vehicle function, and NASA’s attempts to develop new launch systems. Tables relating to each launch vehicle’s characteristics are included. The other functions of the Space Shuttle—as a scientific laboratory, staging area for repair missions, and a prime element of the Space Station program—are discussed in the next chapter, Human Spaceflight. This chapter also provides a brief review of launch systems in the past decade, an overview of policy relating to launch systems, a summary of the management of NASA’s launch systems programs, and tables of funding data. The Last Decade Reviewed (1979–1988) From 1979 through 1988, NASA used families of ELVs that had seen service during the previous decade. -

Grail): Extended Mission and Endgame Status

44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2013) 1777.pdf GRAVITY RECOVERY AND INTERIOR LABORATORY (GRAIL): EXTENDED MISSION AND ENDGAME STATUS. Maria T. Zuber1, David E. Smith1, Sami W. Asmar2, Alexander S. Konopliv2, Frank G. Lemoine3, H. Jay Melosh4, Gregory A. Neumann3, Roger J. Phillips5, Sean C. Solomon6,7, Michael M. Watkins2, Mark A. Wieczorek8, James G. Williams2, Jeffrey C. Andrews-Hanna9, James W. Head10, Wal- ter S. Kiefer11, Isamu Matsuyama12, Patrick J. McGovern11, Francis Nimmo13, G. Jeffrey Taylor14, Renee C. Weber15, Sander J. Goossens16, Gerhard L. Kruizinga2, Erwan Mazarico3, Ryan S. Park2 and Dah-Ning Yuan2. 1Dept. of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02129, USA ([email protected]); 2Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technol- ogy, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; 3NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; 4Dept. of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; 5Planetary Science Directorate, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302, USA; 6 Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964, USA; 7Dept. of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC 20015, USA; 8Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, 94100 Saint Maur des Fossés, France; 9Dept. of Geophysics and Center for Space Resources, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO 80401, USA; 10Dept. of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912, USA; 11Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX 77058, USA; 12Lunar and Planetary Laborato- ry, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA; 13Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA; 14Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA; 15NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL 35805, USA, 16University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA. -

Skylab Attitude and Pointing Control System

I' NASA TECHNICAL NOTE SKYLAB ATTITUDE AND POINTING CONTROL SYSTEM by W. B. Chzlbb and S. M. Seltzer George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Marshall Space Flight Center, Ala. 35812 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, 0. C. FEBRUARY 1971 I I TECH LIBRARY KAFB, NM .. -, - ___.. 0132813 I. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMNT ACCESSION NO. j. KtLIPlbNl'b LAIALOb NO. - NASA- __ TN D-6068 I I 1 1. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE L February 1971 Skylab Attitude and Pointing Control System 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE __- I 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMlNG ORGANlZATlON REPORT # - W... -B. Chubb and S. M. Seltzer I 3. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. 908 52 10 0000 M211 965 21 00 0000 George C. Marshall Space Flight Center I' 1. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama 35812 L 13. TYPE OF REPORY & PERIOD COVERED - _-- .. .- __ 2. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AN0 ADORES5 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Technical Note Washington, D. C. 20546 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE -. - - I 5. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES Prepared by: Astrionics Laboratory Science and Engineering Directorate ~- 6. ABSTRACT NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center is developing an earth-orbiting manned space station called Skylab. The purpose of Skylab is to perform scientific experiments in solar astronomy and earth resources and to study biophysical and physical properties in a zero gravity environment. The attitude and pointing control system requirements are dictated by onboard experiments. These requirements and the resulting attitude and pointing control system are presented. 18 .- 0 1 STR inUT I ONSmTEMeNT Space station Control moment gyro Unclassified - Unlimited Attitude control -~ 9. -

Rex D. Hall and David J. Shayler

Rex D. Hall and David J. Shayler Soyuz A Universal Spacecraft ruuiiMicPublishedu 11in1 aaaundiiuiassociationi witwimh ^^ • Springer Praxis Publishing PRHB Chichester, UK "^UF Table of contents Foreword xvii Authors' preface xix Acknowledgements xxi List of illustrations and tables xxiii Prologue xxix ORIGINS 1 Soviet manned spaceflight after Vostok 1 Design requirements 1 Sever and the 1L: the genesis of Soyuz 3 The Vostok 7/1L Soyuz Complex 4 The mission sequence of the early Soyuz Complex 6 The Soyuz 7K complex 7 Soyuz 7K (Soyuz A) design features 8 The American General Electric concept 10 Soyuz 9K and Soyuz 1 IK 11 The Soyuz Complex mission profile 12 Contracts, funding and schedules 13 Soyuz to the Moon 14 A redirection for Soyuz 14 The N1/L3 lunar landing mission profile 15 Exploring the potential of Soyuz 16 Soyuz 7K-P: a piloted anti-satellite interceptor 16 Soyuz 7K-R: a piloted reconnaissance space station 17 Soyuz VI: the military research spacecraft Zvezda 18 Adapting Soyuz for lunar missions 20 Spacecraft design changes 21 Crewing for circumlunar missions 22 The Zond missions 23 The end of the Soviet lunar programme 33 The lunar orbit module (7K-LOK) 33 viii Table of contents A change of direction 35 References 35 MISSION HARDWARE AND SUPPORT 39 Hardware and systems 39 Crew positions 40 The spacecraft 41 The Propulsion Module (PM) 41 The Descent Module (DM) 41 The Orbital Module (OM) 44 Pyrotechnic devices 45 Spacecraft sub-systems 46 Rendezvous, docking and transfer 47 Electrical power 53 Thermal control 54 Life support 54 -

Space Rescue Ensuring the Safety of Manned Space¯Ight David J

Space Rescue Ensuring the Safety of Manned Space¯ight David J. Shayler Space Rescue Ensuring the Safety of Manned Spaceflight Published in association with Praxis Publishing Chichester, UK David J. Shayler Astronautical Historian Astro Info Service Halesowen West Midlands UK Front cover illustrations: (Main image) Early artist's impression of the land recovery of the Crew Exploration Vehicle. (Inset) Artist's impression of a launch abort test for the CEV under the Constellation Program. Back cover illustrations: (Left) Airborne drop test of a Crew Rescue Vehicle proposed for ISS. (Center) Water egress training for Shuttle astronauts. (Right) Beach abort test of a Launch Escape System. SPRINGER±PRAXIS BOOKS IN SPACE EXPLORATION SUBJECT ADVISORY EDITOR: John Mason, B.Sc., M.Sc., Ph.D. ISBN 978-0-387-69905-9 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York Springer is part of Springer-Science + Business Media (springer.com) Library of Congress Control Number: 2008934752 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. # Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2009 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a speci®c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here.