Sound Symbolism and Synaesthesia: Synaesthetes’ Sensitivity to Sound Symbolism and the Role of Sound Symbolism in Lexical-Gustatory Synaesthesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saga Jacques Vabre/P.27-34

PAR JEAN WATIN-AUGOUARD (saga ars, de l’or en barre Mars, ou comment une simple pâte à base de lait, de sucre et d’orge recouverte d’une couche de caramel, le tout enrobé d’une fine couche de chocolat au lait est devenue la première barre chocolatée mondiale et l’un des premiers produits nomades dans l’univers de la confiserie. (la revue des marques - n°46 - avril 2004 - page 27 saga) Franck C. Mars ne reçu jamais le moindre soutien des banques et fit de l’autofinancement une règle d’or, condition de sa liberté de créer. Celle-ci est, aujourd’hui, au nombre des cinq principes du groupe . Franck C. Mars, 1883-1934 1929 - Franck Mars ouvre une usine ultramoderne à Chicago est une planète pour certains, le dieu de la guerre pour d’autres, une confiserie pour tous. Qui suis-je ?… Mars, bien sûr ! Au reste, Mars - la confiserie -, peut avoir les trois sens pour les mêmes C’ personnes ! La planète du plaisir au sein de laquelle trône le dieu Mars, célèbre barre chocolatée dégustée dix millions de fois par jour dans une centaine de pays. Mars, c’est d’abord le patronyme d’une famille aux commandes de la société du même nom depuis quatre générations, société - cas rare dans l’univers des multinationales -, non côtée en Bourse. Tri des œufs S’il revient à la deuxième génération d’inscrire la marque au firmament des réussites industrielles et commerciales exemplaires, et à la troisième de conquérir le monde, la première génération peut se glorifier d’être à l’origine d’une recette promise à un beau succès. -

Non-Wood Forest Products from Conifers

Page 1 of 8 NON -WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 12 Non-Wood Forest Products From Conifers FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-37 ISBN 92-5-104212-8 (c) FAO 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABBREVIATIONS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 - AN OVERVIEW OF THE CONIFERS WHAT ARE CONIFERS? DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE USES CHAPTER 2 - CONIFERS IN HUMAN CULTURE FOLKLORE AND MYTHOLOGY RELIGION POLITICAL SYMBOLS ART CHAPTER 3 - WHOLE TREES LANDSCAPE AND ORNAMENTAL TREES Page 2 of 8 Historical aspects Benefits Species Uses Foliage effect Specimen and character trees Shelter, screening and backcloth plantings Hedges CHRISTMAS TREES Historical aspects Species Abies spp Picea spp Pinus spp Pseudotsuga menziesii Other species Production and trade BONSAI Historical aspects Bonsai as an art form Bonsai cultivation Species Current status TOPIARY CONIFERS AS HOUSE PLANTS CHAPTER 4 - FOLIAGE EVERGREEN BOUGHS Uses Species Harvesting, management and trade PINE NEEDLES Mulch Decorative baskets OTHER USES OF CONIFER FOLIAGE CHAPTER 5 - BARK AND ROOTS TRADITIONAL USES Inner bark as food Medicinal uses Natural dyes Other uses TAXOL Description and uses Harvesting methods Alternative -

AUGUST, 1940 TEN CENTS OFFICIAL STATE Vol

SMALL MOUTH BASS AUGUST, 1940 TEN CENTS OFFICIAL STATE Vol. 9—No. 8 PUBLICATION VNGLEIC AUGUST, 1940 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA PUBLISHED MONTHLY by the BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS PENNSYLVANIA BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS Publication Office: 540 Hamilton Street, Allentown. Penna. Executive and Editorial Offices: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Board of Fish Commis CHARLES A. FRENCH sioners, Harrisburg, Pa. Commissioner of Fisheries Ten cents a copy—50 cents a year MEMBERS OF BOARD • CHARLES A. FRENCH, Chairman Elwood City ALEX P. SWEIGART, Editor South Office Bldg., Harrisburg, Pa. MILTON L. PEEK Radnor HARRY E. WEBER NOTE Philipsburg Subscriptions to the PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER should be addressed to the Editor. Submit fee either by check or money order payable to the Common EDGAR W. NICHOLSON wealth of Pennsylvania. Stamps not acceptable. Philadelphia Individuals sending cash do so at their own risk. FRED McKEAN New Kensington PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contribu tions and photos of catches from its readers. Proper H. R. STACKHOUSE credit will be given to contributors. Secretary to Board All contributions returned if accompanied by first class postage. Entered as second class matter at the Post Office C. R. BULLER of Allentown, Pa., under Act of March 3, 1879. Chief Fish Culturist, Bellefonte -tJKi IMPORTANT—The Editor should be notified immediately of change in subscriber's address Please give old and new addresses Permission to reprint will be granted provided proper credit notice is given S Vol. 9. No. 8 ANGLERA"VI^ W i»Cr 1%7. AUGUST 1940 EDITORIAL CONTROLLED BASS CULTURE NTENSE investigation and study of bass culture has been taking place in Pennsylvania in the past few years. -

Phone Follow-Up Dietary Interviewer Procedures Manual

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey PHONE FOLLOW-UP DIETARY INTERVIEWER PROCEDURES MANUAL January 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL HEALTH AND NUTRITION EXAMINATION SURVEY ..................................................... 1-1 1.1 History of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Programs 1-1 1.2 Overview of the Current NHANES .................................................... 1-3 1.2.1 Data Collection.................................................................... 1-4 1.3 Sample Selection................................................................................. 1-6 1.4 Field Organization for NHANES ....................................................... 1-7 1.5 Exams and Interviews in the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) ..... 1-10 1.5.1 Exam Sessions..................................................................... 1-12 1.5.2 Exam Team Responsibilities............................................... 1-13 1.5.3 Examination Components. .................................................. 1-14 1.5.4 Second Exams ..................................................................... 1-18 1.5.5 Sample Person Remuneration. ............................................ 1-19 1.5.6 Report of Exam Findings. ................................................... 1-19 1.5.7 Dry Run Day. ...................................................................... 1-20 1.6 Integrated Survey Information System (ISIS) .................................... 1-21 1.7 Confidentiality and Professional Ethics............................................. -

{ Brad Brace } Pleated Plaid Pamphlet 4 [Accompanies Insatiable

{ brad brace } Pleated Plaid Pamphlet Volume 54 [accompaniment to insatiable abstraction engine] http://www.bbrace.net/abstraction-engine.html bbrace@eskimo. -

Volume Xxxi. Newtown. Conn., Friday, June 23 Idod

The Newtown Bee, VOLUME XXXI. NEWTOWN. CONN., FRIDAY, JUNE 23 IDOD. NUMBER 28 Stepney, GOLDEN WEDDING ANNIVER- - NETIIEION'S CREDITORS GET HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION HUNTINGTOWN JOTTINGS. SATURDAY'S TOWN MEETING SARY CHECKS. EXERCISES. METHODIST CHURCH NEWS. Un'PM som storekeeper! nnd ho.el Votci to Accept W. N. Northrou'i On Purrtny last on of tilt largest " their refuse Of Mr and Mrs C. Mitchell. A Dividend of 40 Cent. Procrara lor Friday Nieht. keeper stop dumping Ofcr. congregation!! which hud been present leroy Per on niuln ob- for a number of In and ashci the road, the yHur gathered the server will a collection and Mallinillut church to greet Miss Funnlo The numerous get up Saturday'! special meeting was at- - CELEBRATED ON WEDNESDAY creditors of the Rev Steele. ash-can- s, refuse-ca- m Crosby, tin celebrated composer of Invocation, Alexander pui chase a few CO noma of the of our AT estate of E. E. deceased, of tended by about voters. Daniel O. (Input religious EVENING THEIR HOME IN Nettloton, Song, "Soldiers' Chorus." and barrels and them to the Boers onus. Mr and Mra Abbott of ,Hlnpey whom there were a In present was chairman. After much POOTATUCK. reat many w't e of the brought the distinguished guest to tho this and re- Salutatory, Helen Francis Houlihan. parties, compliments discussion, the following resolution church in their One touring car at an locality adjoining towns, donatore. was 300 nt ceived checks on from the "The Founder of the Ameri- adopted: early hour. Over people were pres-e- Tuesday Essay, are renovat-'n- p to to do honor to the A Large Company of Relatives, can The Gilbert Brothers Resolveu, That the town of New- occasion administrator, Judge Beecher, for Navy," Florence GloverDeet her the house Many came from Kastoti, Monroe and Neighbors and Friends Present. -

19 Gifts & Donations Register 2020

Salford Royal Foundation Trust Covid - 19 Gifts & Donations Register 2020 Date Item donated Quantity / Value Donor details (if available) Conditions (if any) (approximate if available) 30.03.20 Water Bottles Not recorded / £200 N/A None 30.03.20 Toiletries Not recorded/ £200 Faith in Nature Staff who need to use at work 30.03.20 Carex Soap. Body wash etc. Not recorded / £1000 Stacey Pollard B6 None 31.03.20 CE approved Gloves 3 boxes / £50 Radiology 2 @ SRFT None April IPad / tablets 10 / £3500 BNYMellon April Tablets/IPad 3 / £1000 Leona April Tablets/IPad 14 / £4500 Ann Marie Travers 2 x intensive care, 2 x high dependency, 2 x ward H2, 2 x H3, 2 xH4, 2 x H5, 1 x Christie's Salford Royal, 1 x H6 April Toys and crafts Not recorded / £4000 RMS International Bury Community services for vulnerable children and children of NHS staff April Bunches of Flowers 60 / £600 Government of Kenya 01.04.20 Milk Tray 200g boxes of Chocolates 100 / £400 West Road - Local shop Wards 1 and 2 and community 02.04.20 Survival packs 50 / £200 Tzu Chi foundation, None 02.04.20 Chocolates 1000 Thornton's None 03.04.20 Pizzas 100 / £500 Due Amici Restaurant. None 03.04.20 Weetabix drinks 76 / £50 Community - Gems at work None 03.04.20 Kind Protein Bars 4 large boxes / £40 Community - Gems at work None 04.04.20 Fresh Bakery produce Not recorded / £100 Polish Centre " Wimow" M/C None 04.04.20 Masks. Aprons, Gloves Not recorded / £100 Skin Clinic Manchester None 07.04.20 PPE Equipment Not recorded / 200 ITV None 07.04.20 Weetabix drinks Not recorded / £1000 Community -

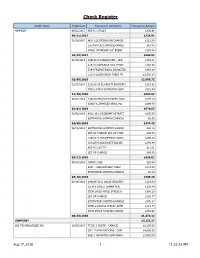

Check Register

Check Register Vendor Name Check Date Transaction Description Transaction Amount 4IMPRINT 09/21/2017 REF PO 175823 $326.91 09/21/2017 $326.91 10/19/2017 ADD' LOCATION RUN CHARGE $121.50 ESTIMATED SHIPPING/HANDLI $47.82 #8921 STANDARD 10" EVENT $391.50 10/19/2017 $560.82 02/08/2018 109148-S CUBANO PEN - OPA $348.21 119373 ADHESIVE CELL PHON $192.98 7194 PROMOTIONAL DRAWSTRI $489.19 2213 CLOSED BACK TABLE TH $1,050.34 02/08/2018 $2,080.72 02/15/2018 134226-10 ECONOMY BACKDRO $316.88 39212-STS-S STANDARD SHAP $322.94 02/15/2018 $639.82 03/01/2018 144160 RECYCLED PAPER TWO $275.14 85015-S ZIPPERED VINYL PO $699.79 03/01/2018 $974.93 03/08/2018 8922-36-L ECONOMY RETRACT $265.50 ESTIMATED SHIPPING/HANDLI $8.95 03/08/2018 $274.45 06/13/2018 ESTIMATED SHIPPING/HANDLI $40.18 SET-UP CHARGE SET-UP CHAR $49.50 146012-5 TRIUMPHANT ACRYL $296.34 110325-S ASSOCIATE RINGBI $249.49 REF PO 183779 $11.01 SET UP CHARGE $49.50 06/13/2018 $696.02 06/20/2018 CARRY CASE $25.00 5957 - CONVERTIBLE TABLE $174.89 ESTIMATED SHIPPING/HANDLI $8.49 06/20/2018 $208.38 08/16/2018 106836-1312 VALUE GROCERY $129.00 ITEM #102557 SAMBA PEN $250.44 ITEM 18035 APPLE STRESS R $248.28 SET UP CHARGE $209.77 ESTIMATED SHIPPING/HANDLI $165.17 ITEM #108/463 SMILEY ADHE $213.74 ITEM #6622 5-PRONG HIGHLI $256.92 08/16/2018 $1,473.32 4IMPRINT $7,235.37 806 TECHNOLOGIES INC 10/05/2017 TITLE 1 CRATE - CAMPUS $2,250.00 CIP - PLAN4LEARNING - CAM $4,000.00 BULLY REPORTER SOFTWARE - $3,600.00 Aug 17, 2018 - 1 - 11:22:13 AM Check Register Vendor Name Check Date Transaction Description Transaction -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13Ra MARCH 1973 3309

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13ra MARCH 1973 3309 Tom Weeks Limited Mini Cafeteria Limited Turner & Backhouse Limited Minx (Melton Mowbray) Limited Witro (Household Appliances) Manufacturing Co. Limited Opals Limited Zilkha Bros. Limited Pal (Melton Mowbray) Limited Zoom Too Limited Pedigree Chum Limited LIST 3013 Pet-A-Pet Limited Amco Metals Limited Petsaid Limited A. R. Gay Limited Petsway Limited A. W. Chambers Securities Limited Pettfish Limited Berjer Holdings Limited Revels (Confectionery) Limited Berjer Securities Limited Burnby Engineers Limited Bowers & Ford Limited Sam Limited Boyle & Coughlan Limited Spangles Limited Swoop Limited C. & F. Transport (Midlands) Limited Casilla (Brixham) Limited Topic (Confectionery) Limited Treets Limited Dry Cleaning Centre (Export) Limited, The Trill (Melton Mowbray) Limited Tunes Limited Farthing Films Limited Twix Limited Godalming Caterers Limited Whiska* Limited Graphotype Development Limited R. W. Westley, Registrar of Companies. Hallmark Garages Limited Home & Pleasure Loans Limited Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 353 (5) of the Hygenic Dental Brush Company Limited Companies Act, 1948, mat the names of the undermentioned Companies have been struck off the Register. Such Com- Integrant Improvements Limited panies are accordingly dissolved as from the date of the publication of this notice. J. & B. Erection Services Limited LIST 3021 K. & G. Supplies (Fulham) Limited A. E. Mann (Stanmore) Limited Albert Hahn & Son Limited Leagrave Motor Company Limited Arctic Food Limited Leman Street -

Trade Mark Opposition Decision (O/440/02)

TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION No. 2006992 BY SOCIÉTÉ DES PRODUITS NESTLÉ S.A. TO REGISTER THE TRADE MARK: IN CLASS 30 AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER No. 47138 BY MARS UK LIMITED TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF Application No. 2006992 by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A. to register a trade mark in Class 30 IN THE MATTER OF Opposition thereto under No. 47138 by Mars UK Limited BACKGROUND 1) On 20 December 1994 Société des Produits Nestlé S.A. applied to register the following trade mark: The application was examined and accepted and published on 2 April 1997 in respect of a specification in Class 30 which reads: sugar confectionery. It was published with the following description: “This mark consists of the three-dimensional shape represented above”. 2) On 2 July 1997 Mars UK Limited filed notice of opposition to this application. At the hearing the opponents relied upon the following grounds of opposition: (i) the trade mark in suit is devoid of distinctive character and so its registration would be contrary to section 3(1)(b) of the Act (ii) the trade mark in suit is in common usage by various traders in the United Kingdom and so that registration would be contrary to section 3(1)(d) of the Act 3) The applicants filed a counterstatement in which they denied the grounds of opposition. 4) Both parties filed evidence and seek an award of costs. 5) The matter came to be heard on 30 May 2002 when the opponents were represented by Mr Michael Bloch of Her Majesty’s Counsel, instructed by Clifford Chance and the applicants were represented by Mr Geoffrey Hobbs of Her Majesty’s Counsel, instructed by Nestlé UK Limited Group Legal & Secretarial Department. -

Penguintasters

PenguinTasters An extract from The Fry Chronicles by Stephen Fry www.penguin.co.uk/tasters The Fry Chronicles by Stephen Fry Copyright Stephen Fry, 2010 All rights reserved Penguin Books Ltd www.penguin.co.uk/tasters The Fry Chronicles is available to buy from Penguin Paperback | eBook and is also available in the Kindle Store and the iBookstore Work is more fun than fun Noël Coward I really must stop saying sorry; it doesn’t make things any better or worse. If only I had it in me to be all fi erce, fearless and forthright instead of forever sprinkling my discourse with pitiful retractions, apologies and prevarications. It is one of the reasons I could never have been an artist, either of a literary or any other kind. All the true artists I know are uninterested in the opinion of the world and wholly unconcerned with self-explanation. Self-revelation, yes, and often, but never self-explanation. Artists are strong, bloody- minded, diffi cult and dangerous. Fate, or laziness, or cowardice cast me long ago in the role of entertainer, and that is what I found myself, throughout my twenties, becoming, though at times a fatally over-earnest, over- appeasing one, which is no kind of entertainer at all, of course. Wanting to be liked is often a very unlikeable characteristic. Certainly I don’t like it in myself. But then, there is a lot in myself that I don’t like. Twelve years ago I wrote a memoir of my childhood and adolescence called Moab is My Washpot, a title that confused no one, so clear, direct and obvious was its meaning and reference. -

Poetry for Remedial Seventh and Eighth Graders with Selections from Ballads, Emily Dickinson, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Julia De Burgos

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1985 Volume I: Poetry Poetry For Remedial Seventh and Eighth Graders with Selections from Ballads, Emily Dickinson, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Julia de Burgos Curriculum Unit 85.01.08 by Anne Wedge Poetry is a suitable method for teaching comprehension skills in the middle school. It is succinct. A ballad or a short poem can contain in itself many poetic devices which also apply to prose. The language of poetry makes the reader more aware of nuances of meaning and will deepen his thinking power as critical and appreciative skills develop. A good poem, carefully selected, can be read, analyzed, and imitated, all in one class period without abridging thinking processes. The remedial reader has little tolerance for long assignments. Such a pupil becomes bored quickly and with loss of interest the usefulness of a unit if over. With this special consideration in mind what is presented here is designed to appeal to remedial seventh and eighth graders and to provide them with pleasure and enjoyment. The first step in this appeal is to introduce the unit with a tape developed by some of my seventh grade girls. They have written lyrics and sing as a group to an instrumental background. The purpose at the onset is to rivet the attention of the group to what a few can do with music and poetry. No attempt will be made to include biographical or regional emphasis in this unit. It is my intent to present poetry which would have universal appeal.