Global Solidarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

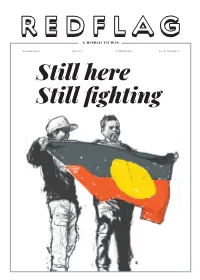

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Commonwealth Responsibility and Cold War Solidarity Australia in Asia, 1944–74

COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 DAN HALVORSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463236 ISBN (online): 9781760463243 WorldCat (print): 1126581099 WorldCat (online): 1126581312 DOI: 10.22459/CRCWS.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A1775, RGM107. This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix 1 . Introduction . 1 2 . Region and regionalism in the immediate postwar period . 13 3 . Decolonisation and Commonwealth responsibility . 43 4 . The Cold War and non‑communist solidarity in East Asia . 71 5 . The winds of change . 103 6 . Outside the margins . 131 7 . Conclusion . 159 References . 167 Index . 185 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Cathy Moloney, Anja Mustafic, Jennifer Roberts and Lucy West for research assistance on this project. Thanks also to my colleagues Michael Heazle, Andrew O’Neil, Wes Widmaier, Ian Hall, Jason Sharman and Lucy West for reading and commenting on parts of the work. Additionally, I would like to express my gratitude to participants at the 15th International Conference of Australian Studies in China, held at Peking University, Beijing, 8–10 July 2016, and participants at the Seventh Annual Australia–Japan Dialogue, hosted by the Griffith Asia Institute and Japan Institute for International Affairs, held in Brisbane, 9 November 2017, for useful comments on earlier papers contributing to the manuscript. -

Behind and Beyond the Crisis Guglielmo Carchedi, International Socialism N°132, October 11

Behind and beyond the crisis Guglielmo Carchedi, International Socialism n°132, October 11 The 2007 financial crisis has reignited the discussion on crises, their origin and possible remedies.1 At present the most influential thesis on the left sees the crisis as caused by underconsumption and recommends Keynesian policies as a solution. This paper argues that we should understand the crisis from the perspective of Karl Marx’s “law of the tendential fall in the average rate of profit” (ARP), for short “the law”. Its characteristic feature is that technological progress decreases the rate of profit, rather than increasing it as is usually assumed. Let us see why. The law in a nutshell The law’s essential features are as follows: (1) Capitalists compete against each other by introducing new means of production incorporating new technologies. This is not the only form of competition but it is by far the most important one for understanding the dynamics of the crisis.2 (2) The new means of production increase the efficiency (output of use values per unit of capital invested) of the technological leaders in the productive sectors. (3) At the same time, the new technologies are designed to replace labourers with means of production. Therefore the technological leaders’ proportion of capital invested in means of production relative to that in labour power, the organic composition of capital, increases. Unemployment follows. (4) Since only labour creates value, less labour power employed means less (surplus) value created by high‐ technology capitals. All other things being equal, the ARP falls: ‘‘The rate of profit does not fall because labour becomes less productive, but because it becomes more productive”.3 Notice that it is the rate of profit and not the mass of profits that falls. -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Bioethics

Solidarity: reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx This report was commissioned by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCoB) and was jointly funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Nuffield Foundation. The award was managed by the Economic and Social Research Council on behalf of the partner organisations, and some additional funding was made available by NCoB. For the duration of six months in 2011, Professor Barbara Prainsack was the NCoB Solidarity Fellow, working closely with fellow author Dr Alena Buyx, Assistant Director of NCoB. Disclaimer The report, whilst funded jointly by the AHRC, the Nuffield Foundation and NCoB, does not necessarily express the views and opinions of these organisations; all views expressed are those of the authors, Professor Barbara Prainsack and Dr Alena Buyx. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is an independent body that examines and reports on ethical issues in biology and medicine. It is funded jointly by the Nuffield Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, and has gained an international reputation for advising policy makers and stimulating debate in bioethics. www.nuffieldbioethics.org The Nuffield Foundation is an endowed charitable trust that aims to improve social wellbeing in the widest sense. It funds research and innovation in education and social policy and also works to build capacity in education, science and social science research. www.nuffieldfoundation.org Established in April 2005, the AHRC is a non-Departmental public body. It supports world-class research that furthers our understanding of human culture and creativity. www.ahrc.ac.uk © Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx ISBN: 978-1-904384-25-0 November 2011 Printed in the UK by ESP Colour Ltd. -

Reflections on the Venezuelan Transition from a Capitalist Representative to a Socialist Participatory Democracy What Are Planners to Do?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Reflections on the Venezuelan Transition from a Capitalist Representative to a Socialist Participatory Democracy What Are Planners to Do? by Clara Irazábal and John Foley Venezuela is experiencing a transitional political process in which the government and the majority of Venezuelans want to move from a capitalist representative democracy to a more socialist participatory democracy. This transition is enmeshed in complexities, contradictions, and political opposition. Reflection on the experience of accompanying neighborhood groups in local decision making in Caracas from 2002 to 2006 suggests that planning practitioners and scholars can be allies in the grassroots processes of empowerment and self-determination of local communities and advocates and active agents in the “trickling-up” of greater planning participation to upper levels of government. Keywords: Venezuela, Transition, Socialist participatory democracy, People’s power, Councils Clara Irazábal is assistant professor of international urban planning in the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation of Columbia University. John Foley (d. 2006) was a professor at the Instituto de Urbanismo of the Universidad Central de Venezuela. Irazábal honors his memory and, on his behalf, thanks all of the participants in the two case studies discussed in this article. Additionally, she thanks Gabriel Fumero, Silvia Fumero, Gonzalo Gómez, Teresa Rodríguez, Niurca Rodríguez, Werther Saldoval, and Gustavo Vizcuña for sharing their valuable insights as participants and/or observers of communal councils in Venezuela. Lastly, she acknowledges enriching comments on previous drafts by Steve Ellner and Daniel Hellinger. -

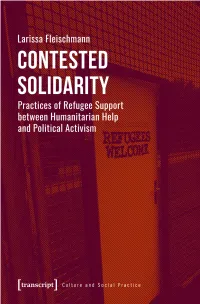

Practices of Refugee Support Between Humanitarian Help And

Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Culture and Social Practice Larissa Fleischmann, born in 1989, works as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Human Geography at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. She received her PhD from the University of Konstanz, where she was a member of the Centre of Excellence »Cultural Foundations of Social Integration« and the Social and Cultu- ral Anthropology Research Group from 2014 to 2018. Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism Dissertation of the University of Konstanz Date of the oral examination: February 15, 2019 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. Thomas G. Kirsch 2nd reviewer: PD Dr. Eva Youkhana 3rd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Judith Beyer This publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Re- search Foundation) - Project number 448887013. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The field research for this publication was funded by the Centre of Excellence “Cultural Foundations of Social Integration”, University of Konstanz. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY- NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. For details go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Permission to use the text for commercial purposes can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

The "Fifth International?": Dissidents in Eastern Europe

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 1 Issue 6 Article 2 11-1981 The "Fifth International?": Dissidents in Eastern Europe Wieland Zademach Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zademach, Wieland (1981) "The "Fifth International?": Dissidents in Eastern Europe," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 1 : Iss. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol1/iss6/2 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE "FIFTH INTERNATIONAL ?": DISSIDENTS IN EASTERN EUROPE* by Wieland Zademach Dr. Wieland Zademach is a Lutheran pastor in Streitau, _West Germany. His doctoral dissertation was written in 1971 about the Christian-Marxist dialogue of the 1960' s and published in 1973 in DUsseldorf as Marxistischer Atheismus und die biblische Botschaft von der Rechtfertigung des Gottlosen. In 1979, his book Eurokommu nismus�-Weg oder Irrweg was published in Munich. A new "ghost" seems to be stalking in Europe, and particularly in Eastern Europe, in the shape of civil rightists, dissidents, and defenders of human rights. The Polish writer A. Szczypiorski said two years ago that "no other political figur= has had such a flourishing career in European intellectual life during the last few y=ars as tqe dis- 1 sident." And clearly this career is giving increasingly frequent headaches to govern- ments in Eastern Europe. -

Alasdair Macintyre and Trotskyism

BlackledgeKnight-09_Layout 1 12/29/10 8:07 AM Page 152 9 Alasdair MacIntyre and Trotskyism Alasdair MacIntyre began his literary career in 1953 with Marxism: An Interpretation. According to his own account, in that book he attempted to be faithful to both his Christian and his Marxist beliefs (MacIntyre 1995d). Over the course of the 1960s he abandoned both (MacIntyre 2008k, 180). In 1971 he introduced a collection of his essays by rejecting these and, indeed, all other attempts to illuminate the human condition (MacIntyre 1971b, viii). Since then, MacIntyre has of course re-embraced Christianity, although that of the Catholic Church rather than the An - glicanism to which he originally adhered. It seems unlikely, at this stage, that he will undertake a similar reconciliation with Marxism. Nevertheless, as MacIntyre has frequently reminded his readers, most recently in the prologue to the third edition of After Virtue (2007), his rejection of Marxism as a whole does not entail a rejection of every insight that it has to o ffer. MacIntyre’s current audience tends to be un - interested in his Marxism and consequently remains in ignorance not only of his early Marxist work but also of the context in which it was written. MacIntyre not only wrote from a Marxist perspective but also belonged to a number of Marxist organisations, which, to di ffering de - grees, made political demands on their members from which intellec tu - 152 BlackledgeKnight-09_Layout 1 12/29/10 8:07 AM Page 153 Alasdair MacIntyre and Trotskyism 153 als were not excluded. Even the most insightful of MacIntyre’s admirers tend to treat the subject of these political a ffiliations as an occasion for mild amusement (Knight 1998, 2). -

From Cold War Solidarity to Transactional Engagement Reinterpreting Australia’S Relations with East Asia, 1950–1974

From Cold War Solidarity to Transactional Engagement Reinterpreting Australia’s Relations with East Asia, 1950–1974 ✣ Dan Halvorson Introduction The academic treatment of Australia’s engagement with Asia has concentrated almost entirely on Australian initiatives in the region and their perceived successes and failures. Historical work has focused on Australia’s postwar re- lationships with Britain and the United States and their ramifications for Canberra’s Cold War policy of “forward defence,” including involvement in the Vietnam War.1 This article offers a reinterpretation of the historical pat- tern of Australia’s Cold War engagement with East Asia based on new archival research conducted in Australia and the United Kingdom.2 The article marks an important shift in focus from previous work in seeking to emphasize the agency enjoyed by non-Communist East Asian states in their relationships with Australia during the Cold War. Australia’s outlook on the world tended to reflect global British Empire concerns until the Pacific War of 1941–1945 thanks to its Anglo-Celtic– derived society and geographic isolation on the fringes of an Asian-Pacific region dominated by European colonial powers. The fall of Britain’s Sin- gapore base to the advancing Japanese in February 1942 brought home to Australians the geographic reality that their country was firmly located in 1. See, for example, Gregory Pemberton, All the Way: Australia’s Road to Vietnam (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1987); Peter Edwards, with Gregory Pemberton, Crises and Commitments: The Politics and Diplomacy of Australia’s Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1965 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1992); Garry Woodard, Asian Alternatives: Australia’s Vietnam Decision and Lessons on Going to War (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2004); and Peter Edwards, Australia and the Vietnam War (Sydney: New South Publishing and Australian War Memorial, 2014). -

Transforming Charity Into Solidarity and Justice

Global Citizenship Education: Module 1 Transforming Charity into Solidarity and Justice SASKATCHEWAN COUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION WWW.EARTHBEAT.SK.CA T: 306-757-4669 SSASKACTCHEWANI CCOUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION We connect people and organizations to the information and ideas they need to take meaningful actions, and to be great global citizens. For more information visit our website, join us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, or drop us a line. P: 306.757.4669 F: 306.757.3226 2138 McIntyre Street, Regina, SK S4P 2R7 [email protected] www.earthbeat.sk.ca SaskCIC @SaskCIC scicyouth Undertaken with the financial support of Global Affairs Canada SCIC would like to give a special thank you to the contributors in the development of Module 1: Transforming Charity into Solidarity and Justice. Contents TRANSFORMING CHARITY INTO SOLIDARITY AND JUSTICE . 3 WHAT’s in THE MODULE. .4 EDUCATION THEORY AND METHODOLOGY . 6 SOCIAL STUDIES CURRICULUM OUTCOMES AND INDICATORS. .7 LESSON #1 . .9 DEFINING CHARITY, JUSTICE, AND SOLIDARITY 1 Curriculum Outcomes What You’ll Need Before Activities • Introduction to Module 1 During Activities • Looking into Charity, Justice and Solidarity Fr After Activities • Checking for Understanding: Standing on the Spectrum Activity LESSON #2. .16 IDENTIFYING THE ROOT CAUSES OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS 2 Curriculum Outcomes What You’ll Need Before Activities • Entrance Slip • Babies in the River Parable During Activities • “Finding the Root Cause by Asking WHY” by Kailee Howorth Fr • Finding the Root Causes Activity • Looking into Solidarity After Activities • Checking for Understanding: Reviewing Student Answers to Finding Root Causes Activity MODULE 1: TRANSFORMING CHARITY INTO SOLIDARITY AND JUSTIce SASKATCHEWAN COUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION WWW.EARTHBEAT.SK.CA T: 306-757-4669 PAGE 1 LESSON #3. -

November, 1957 Friendship and Solidarity Among Socialist Countries

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified November, 1957 Friendship and Solidarity Among Socialist Countries Citation: “Friendship and Solidarity Among Socialist Countries,” November, 1957, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Kim Il Sung Works, Vol. 11, January-December 1957 (Pyongyang, Korea: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1982), 310-322. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117756 Summary: Kim Il Sung's article, originally published in Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn, thanks the Soviet Union and China for assisting North Korea while deriding American foreign policy. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: English Contents: English Transcription Friendship and Solidarity Among Socialist Countries, November 1957 [Source: Kim Il Sung Works, Vol. 11, January-December 1957 (Pyongyang, Korea: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1982), 310-322.] FRIENDSHIP AND SOLIDARITY AMONG SOCIALIST COUNTRIES Article Published in the November 1957 Issue of the Soviet Magazine Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn Forty years have elapsed since the triumph of the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. In this not-too-long period, fundamental changes have taken place in the history of mankind. We are now living in a new historical era. A major characteristic of this era is that socialism has become a powerful worldwide system. There was only a single socialist state in the world when the Soviet people started building socialism after the victorious October Revolution. The present situation, however, is radically different. The idea of the October Revolution which gripped masses of people has become a great material force capable of transforming human society; socialism now finds itself beyond the bounds of one country, the Soviet Union.