Foreword: Ksawery Pruszyn´Ski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reconstruction of Nations

The Reconstruction of Nations The Reconstruction of Nations Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999 Timothy Snyder Yale University Press New Haven & London Published with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Fund of Yale University. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Snyder, Timothy. The reconstruction of nations : Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, ‒ / Timothy Snyder. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN --- (alk. paper) . Europe, Eastern—History—th century. I. Title. DJK. .S .—dc A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Marianna Brown Snyder and Guy Estel Snyder and in memory of Lucile Fisher Hadley and Herbert Miller Hadley Contents Names and Sources, ix Gazetteer, xi Maps, xiii Introduction, Part I The Contested Lithuanian-Belarusian Fatherland 1 The Grand Duchy of Lithuania (–), 2 Lithuania! My Fatherland! (–), 3 The First World War and the Wilno Question (–), 4 The Second World War and the Vilnius Question (–), 5 Epilogue: -

The University of Arizona

Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke- White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Caldwell, Jay E. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:56:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/316913 ERSKINE CALDWELL, MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE, AND THE POPULAR FRONT (MOSCOW 1941) by Jay E. Caldwell __________________________ Copyright © Jay E. Caldwell 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Jay E. Caldwell, titled “Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke-White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941),” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Dissertation Director: Jerrold E. Hogle _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Daniel F. Cooper Alarcon _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Jennifer L. Jenkins _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Robert L. McDonald _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Charles W. Scruggs Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

MAKING SENSE of CZESLAW MILOSZ: a POET's FORMATIVE DIALOGUE with HIS TRANSNATIONAL AUDIENCES by Joanna Mazurska

MAKING SENSE OF CZESLAW MILOSZ: A POET’S FORMATIVE DIALOGUE WITH HIS TRANSNATIONAL AUDIENCES By Joanna Mazurska Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Michael Bess Professor Marci Shore Professor Helmut W. Smith Professor Frank Wcislo Professor Meike Werner To my parents, Grazyna and Piotr Mazurscy II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my Dissertation Committee: Michael Bess, Marci Shore, Helmut Smith, Frank Wcislo, and Meike Werner. Each of them has contributed enormously to my project through providing professional guidance and encouragement. It is with immense gratitude that I acknowledge the support of my mentor Professor Michael Bess, who has been for me a constant source of intellectual inspiration, and whose generosity and sense of humor has brightened my academic path from the very first day in graduate school. My thesis would have remained a dream had it not been for the institutional and financial support of my academic home - the Vanderbilt Department of History. I am grateful for the support from the Vanderbilt Graduate School Summer Research Fund, the George J. Graham Jr. Fellowship at the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, the Max Kade Center Graduate Student Research Grant, the National Program for the Development of the Humanities Grant from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, and the New York University Remarque Institute Visiting Fellowship. I wish to thank to my friends at the Vanderbilt Department of History who have kept me company on this journey with Milosz. -

DZIEDZICTWO KRESÓW. Kultura

Dziedzictwo-Kresow-III:Ignatianum 18/12/14 13:52 Page 1 5+ 156 mm 14 156 mm +5 5+ Dziedzictwo Dziedzictwo KrEsÓwwyznania– narody – kultura • Dziedzictwo Kolejny tom „Dziedzictwo Kresów: kultura, narody, wyznania” obejmuje szero- KrEsÓw kie spektrum problematyki związanej z Kresami Rzeczypospolitej. Zawarte w nim artykuły omawiają podjęte zróżnicowane zagadnienia w sposób intere- sujący, w oparciu o źródła i opracowania. Co warte podkreślenia i szczególnie cenne, nie unika się tu osobistych relacji zamieszkałych na Kresach ludzi. Zbiór artykułów poszerza wiedzę czytelnika o problematykę dotychczas nie opraco- kultura – narody – wyznania waną, bądź z biegiem czasu mogącą ulec zapomnieniu. Wszystkie zamieszczone w tym tomie artykuły są ciekawe, wartościowe i na wysokim poziomie. dr hab. Ewa Danowska (UJK w Kielcach) Publikacja zawiera interesujące teksty dotyczące kulturowej, narodowej i wy- znaniowej specyfiki Kresów w okresie od XIX do początków XXI wieku (…). Należy podkreślić, że zamieszczone (…) teksty wyraźnie sygnalizują, jak duże zainteresowanie wielu dyscyplin naukowych budzi problematyka dziedzictwa 232 mm Kresów. Wśród autorów odnajdujemy bowiem nie tylko historyków czy bada- czy dziejów edukacji, ale także reprezentantów archeologii, nauk filologicz- nych. Autorzy zwracają uwagę na różnorodne elementy specyfiki życia na Kresach wynikające z kontekstów kulturowych, narodowych czy wyznanio- wych. W rezultacie czytelnik otrzymuje interesujący zbiór tekstów obrazują- cych nie tylko elementy składowe mitu Kresów Wschodnich, ale i doświad- -

'First to Fight'

THE INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL ‘FIRST TO FIGHT’ REMEMBRANCE – COMMISSION FOR THE POLES THE PROSECUTION OF CRIMES AGAINST ON THE FRONT LINES THE POLISH NATION OF WORLD WAR II. ŁÓDŹ 2017 r. Curator: This exhibition consists of archival materials Artur Ossowski and photographs from the collections of: Australian War Memorial (AWM) Script: Imperial War Museum (IWM) Paweł Kowalski Artur Ossowski Institute of National Remembrance Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN) Paweł Spodenkiewicz ( Prof. Janusz Wróbel Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London Magdalena Zapolska-Downar (Instytut Polski i Muzeum im. gen. Sikorskiego, IPMS) Museum of Polish Arms in Kołobrzeg Review of the script: (Muzeum Oręża Polskiego, MOP) Maciej Korkuć PhD Museum of Pro-Independence Traditions in Łódź (Muzeum Tradycji Niepodległościowych, MTN) Art design: Regional Museum in Piotrków Trybunalski dr Milena Romanowska Polish Army Museum in Warsaw (Muzeum Wojska Polskiego, MWP) Illustrations: Jacek Wróblewski National Digital Archive in Warsaw (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe) Maps: KARTA Centre (Ośrodek Karta, OK) Sebastian Kokoszewski Polish Press Agency (Polska Agencja Prasowa, PAP) Typesetting: Master, Łódź Front cover: No. 303 Squadron pilots in front of Hawker Hurricane, 24 October 1940. From left to right: Second Lieutenant Mirosław Ferić (died on 14 February 1942), Canadian Captain John A. Kent, Second Lieutenant Bogdan Grzeszczak (died on 28 Au- gust 1941), Second Lieutenant Jerzy Radomski, Second Lieutenant Jan Zumbach, Second Lieutenant Witold Łokuciewski, Second Lieutenant Bogusław Mierzwa (died on 16 April 1941), Lieutenant Zdzisław Henneberg (died on 12 April 1941), Sergeant Jan Rogowski, and Sergeant Eugeniusz Szaposznikow. (Photo by Stanley Devon/IWM) 3 A member oF the AntI-German CoalitIon World War II ended 70 years ago, but the memory of the conflict is still alive and stirs extreme emotions. -

Federalism and Nationalism in Polish Eastern Policy

Politics&Diplomacy Federalism and Nationalism in Polish Eastern Policy Timothy Snyder As the European Union admits more and more states of the Timothy Snyder is Assistant Professor of former communist bloc, the eastern border of the Euro- History at Yale Univer- pean Union will overlap with a number of other very sity. His most recent book is The Reconstruction important divides: between more and less prosperous states, of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, between western and eastern Christianity, between states Lithuania, Belarus, 1569- with historically friendly ties with the United States and 1999. those without. Integration into the European Union will become far more than a metaphor, as its borders will func- tion like those of a sovereign state. Wh e r e will the European Union find its eastern policy, its Os t p o l i t i k ? During the Cold War, West Germany was the main so u r ce of eastern policy, for good reason. A divided Germany then marked the border of eastern and western Europe. Tod a y , Germany has been reunified, and soon the European Union will enlarge to include Germany’s eastern neighbors, most importantly Poland and Lithuania. The cold war lasted for two ge n e r ations; the new divide between eastern and western Europe promises to last at least as long. Poland and Lithuania will soon become, and long remain, the eastern marches of the European Union. Their ideas and initiatives are likely to guide whatever eastern policy the European Union devises. What exactly their inclinations will be, however, is far from clear. -

Interwar Polish-Jewish Emigration to Palestine

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities History Between anti-Semitism and political pragmatism: Polish perceptions of Jewish national endeavours in Palestine between the two world wars Katarzyna Dziekan Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities History Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Between anti-Semitism and political pragmatism: Polish perceptions of Jewish national endeavours in Palestine between the two world wars Katarzyna Dziekan Since Zionism was endemic within the Polish-Jewish politics of the interbellum, Warsaw’s elites, regardless of their political persuasion, were compelled to take a specific stand on the Zionist ideology and Jewish national aims in Palestine. -

Panorama Histórico De Las Traducciones De La Literatura Polaca Publicadas En España

PANORAMA HISTÓRICO DE LAS TRADUCCIONES DE LA LITERATURA POLACA PUBLICADAS EN ESPAÑA DE 1939 A 1975 ILONA NARĘBSKA TESIS DOCTORAL PANORAMA HISTÓRICO DE LAS TRADUCCIONES DE LA LITERATURA POLACA PUBLICADAS EN ESPAÑA DE 1939 A 1975 ILONA NARĘBSKA 2011 2 PANORAMA HISTÓRICO DE LAS TRADUCCIONES DE LA LITERATURA POLACA PUBLICADAS EN ESPAÑA DE 1939 A 1975 Universidad de Alicante Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Traducción e Interpretación Autora: Ilona Narębska Director: Prof. Dr. Piotr Sawicki Alicante 2011 3 4 AGRADECIMIENTOS A mi Familia, por su paciencia y por haberme dado tanta libertad. Al profesor Piotr Sawicki, por el tiempo dedicado a esta tesis, sus consejos y su precisión. Al profesor Fernando Navarro, por haber confiado en mí y por su apoyo durante todos estos años. A Juanito, por las horas dedicadas a la lectura y corrección de este trabajo, y por un encargo de traducción. A Miguelku, por ser mí guía y familia en este país de adopción y por su buen corazón. A José, porque gracias a él supe que Alicante existía. A Marta, por ver el lado positivo de las cosas. A Ola, por las sesiones, “mano a mano”, de jogging. A Chen, por los sábados en la universidad y su filosofía zen. A Javi, Paola, Dani, Aída y Patrick, por las tutorías y empanadillas chinas compartidas. A Rebeczka y Sofía, por las correcciones de este trabajo y las charlas sobre el significado de las cosas. A todos mis alumnos, por las preguntas a las que no supe responder. A mis compañeros del Departamento, por todo lo que he aprendido de ellos. -

Poland Reacts to the Spanish Right, 1936-1939 (And Beyond)1

1 Affinity and Revulsion: Poland Reacts to the Spanish Right, 1936-1939 (And Beyond)1 Marek Jan Chodakiewicz Poland has customarily viewed Spain through the prism of its own domestic concerns. More specifically, between 1936 and 1939, Spain figured in Poland's public discourse to the extent that the politics, ideas, and circumstances of the Spanish Right were similar to those of its Polish counterpart. The salient features of the Polish Right were its Catholicism, which gave it a universalist frame of reference; traditionalism, which limited the boundaries of its radicalism; anti-Communism, which fueled its rhetoric; anti-Sovietism and anti-Germanism, which defined its security 1 This essay was written for the Historical Society's National Convention at Boston University, May 27-29, 1999, and specifically for the panel “Reaction and Counterrevolution in Spain: Carlism, 1810-1939.” Parts of this paper are based upon my Zagrabiona pamięć: Wojna w Hiszpanii, 1936-1939 [Expropriated Memory: The War in Spain, 1936-1939] (Warszawa: Fronda, 1997) [afterward Zagrabiona]. All unattributed quotes and data are from this work. All translations are mine unless otherwise stated. For assistance with this essay I would like to thank the late Gregory Randolph (University of Chicago), Richard Tyndorf, Wojciech Jerzy Muszyński, Leszek Żebrowski, and Anna Gräfin Praschma. I also benefitted from very generous comments by Professor Alexandra Wilhelmsen (University of Dallas), Professor Carolyn Boyd (University of Texas at Austin), and Dr. Patric Foley. I dedicate this essay to the memory of Gregory Randolph. 2 concerns; and nationalism, which circumscribed its instinct to fight in Spain. This essay considers the extent of the identification of the Polish Right with its Spanish counterpart. -

Newsletter 2019

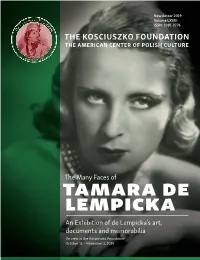

Newsletter 2019 Volume LXVIII ISSN: 1081-2776 Table of Contants Board of Trustees: S t a ff: Alex Storozynski Marek Skulimowski Message from the President _____ 3 Prof. Krzysztof Matyjaszewski Gives a Lecture at the KF _______ 31 Chairman of the Board President and Executive Director Th e 2019 Exchange Program Wanda M. Senko Jolanta Kowalski to the United States ____________ 5 66th Chopin Piano Competition __ 32 Vice–Chair Chief Financial Offi cer Th e Many Faces S. Moniuszko Birth Bicentenary _34 Cynthia Rosicki, Esq. Ewa Zadworna of Tamara de Lempicka __________ 6 Vice–Chair Director of Cultural Aff airs Marcella Sembrich International KF gives ten grants for Summer Andrzej Rojek Barbara Bernhardt Voice Competition ____________ 35 Study – 1934 __________________8 Vice–Chair Director, Washington, D.C. Wieniawski Violin Competition __38 Joseph E. Gore, Esq. Addy Tymczyszyn 84th Ball Highlights ____________ 10 Past Cultural Events ___________39 Corporate Secretary Program Offi cer, Scholarships & A salute to Polish Opera Star ____ 16 Peter S. Novak Grants for Americans Upcoming Events _____________42 Treasurer Malgorzata Szymanska Th e KF Frank Wilczek Award ____ 17 2019–2020 Exchange Exchange Program Offi cer Networking, Professional Career Fellowships and Grants ________44 Margaret Kozlowska Building & Scholarships Event __ 18 Miroslaw Brys, M.D., Ph.D. Rental Events Manager Exchange Program to the U.S. ___45 Th e Kosciuszko Foundation Piotr Chomczynski, Ph.D. Dominika Orwat Alumni Association ____________ 19 2018–2019 Scholarships Hanna Chroboczek Kelker, Ph.D. Development Manager and Grants for Americans _______ 51 Words from our Scholar ________20 Zbigniew Darzynkiewicz, M.D., Ph.D. Alicja Grygiel 2018–2019 KF Members _______64 Ambassador Lee Feinstein Membership Offi cer 2019 Teaching English Rachael Jarosh Izabella Laskowska in Poland Program _____________ 21 In Memoriam _________________ 75 Christopher Kolasa, M.D. -

Ewa Kołodziejczyk Czesław Miłosz in Postwar America

Ewa Kołodziejczyk Czesław Miłosz in Postwar America Ewa Kołodziejczyk Czesław Miłosz in Postwar America Translated by Michał Janowski Managing Editors: Katarzyna I. Michalak & Katarzyna Grzegorek Language Editor: Adam Tod Leverton Associate Editor: Francesca Corazza ISBN 978-83-956696-3-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-83-956696-4-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-069614-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. © 2020 Ewa Kołodziejczyk Published by De Gruyter Poland Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Original Polish edition: Amerykańskie powojnie Czesława Miłosza, 2015 The publication is funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of Humanities in the years 2017-2019 [0025/NPRH5/H21/84/2017]. Translated by Michał Janowski Managing Editors: Katarzyna I. Michalak & Katarzyna Grzegorek Language Editor: Adam Tod Leverton Associate Editor: Francesca Corazza www.degruyter.com Cover illustration: Jeffrey Czum/Pexels Contents Abbreviations — XI Foreword: From the Adventures of a Twentieth-Century Gulliver — XII Acknowledgements — XIV Introduction — 1 Chapter 1: Activités de Surface — 10 The Circumstances of the Departure for the USA