Immediate Effect of Tobacco Chewing in the Form of 'Paan'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harm Reduction Journal Biomed Central

Harm Reduction Journal BioMed Central Research Open Access My first time: initiation into injecting drug use in Manipur and Nagaland, north-east India Michelle Kermode*1, Verity Longleng2, Bangkim Chingsubam Singh2, Jane Hocking3, Biangtung Langkham2 and Nick Crofts1 Address: 1Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Victoria, Australia, 2c/- Project ORCHID, CBCNEI Mission Compound, Guwahati, Assam, India and 3Key Centre for Women's Health, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Victoria, Australia Email: Michelle Kermode* - [email protected]; Verity Longleng - [email protected]; Bangkim Chingsubam Singh - [email protected]; Jane Hocking - [email protected]; Biangtung Langkham - [email protected]; Nick Crofts - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 5 December 2007 Received: 3 July 2007 Accepted: 5 December 2007 Harm Reduction Journal 2007, 4:19 doi:10.1186/1477-7517-4-19 This article is available from: http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/4/1/19 © 2007 Kermode et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: The north-east Indian states of Manipur and Nagaland are two of the six high HIV prevalence states in the country, and the main route of HIV transmission is injecting drug use. Understanding the pathways to injecting drug use can facilitate early intervention with HIV prevention programs. While several studies of initiation into injecting drug use have been conducted in developed countries, little is known about the situation in developing country settings. -

IMS Data Reference Tables

IMS REFERENCE DATA – VERSION 1.7 TABLES 1. Substance .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Local Authority ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Drug Action Team (DAT) ...................................................................................................................................................... 13 4. Nationality ........................................................................................................................................................................... 17 5. Ethnicity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 22 6. Sexual Orientation ............................................................................................................................................................... 22 7. Religion or Belief .................................................................................................................................................................. 22 8. Employment Status .............................................................................................................................................................. 23 9. Accommodation Status -

OCTOBER 2019 Network Bulletin an Important Message from Unitedhealthcare to Health Care Professionals and Facilities

OCTOBER 2019 network bulletin An important message from UnitedHealthcare to health care professionals and facilities. Enter UnitedHealthcare respects the expertise of the physicians, health care professionals and their staff who participate in our network. Our goal is to support you and your patients in making the most informed decisions regarding the choice of quality and cost-effective care, and to support practice staff with a simple and predictable administrative experience. The Network Bulletin was developed to share important updates regarding UnitedHealthcare procedure and policy changes, as well as other useful administrative and clinical information. Where information in this bulletin conflicts with applicable state and/or federal law, UnitedHealthcare follows such applicable federal and/or state law. UnitedHealthcare Network Bulletin October 2019 Table of Contents Front & Center PAGE 3 Stay up to date with the latest news and information. UnitedHealthcare Commercial PAGE 22 Learn about program revisions and requirement updates. UnitedHealthcare Community Plan PAGE 29 Learn about Medicaid coverage changes and updates. UnitedHealthcare Medicare Advantage PAGE 35 Learn about Medicare policy, reimbursement and guideline changes. UnitedHealthcare Affiliates PAGE 37 Learn about updates with our company partners. PREV NEXT 2 | For more information, call 877-842-3210 or visit UHCprovider.com. UnitedHealthcare Network Bulletin October 2019 Table of Contents Front & Center Stay up to date with the latest news and information. Smart Edits Help Speed Up Radiology Program Outpatient Injectable Your Claims Cycle Procedure Code Changes Chemotherapy and Our Smart Edits claims tool catches Effective Jan. 1, 2020, Related Cancer Therapies errors and gives you an opportunity UnitedHealthcare will update Prior Authorization/ to resolve and resubmit a claim the procedure code list for the Notification Updates before it enters the claims cycle. -

Tobacco Use: a Smart Guide

1 Tobacco Use: A Smart Guide “STOPPING TAKES HARD WORK AND A LOT OF EFFORT, BUT – YOU CAN STOP TOBACCO” THE PROCESS OF QUITTING Do you find quitting tobacco difficult? The reason you continue to use tobacco is not because you are weak-willed or irresponsible, but because you are addicted. Nicotine is said to be more addictive than brown sugar (heroin) or cocaine. That is why people find it so difficult to stop, once they are habituated. The quitting process involves three steps: A. Preparation before quitting B. Actual quitting and C. Life after quitting. This manual will guide you through each of these steps. YOU NEED TO KNOW Before trying to quit tobacco you need to know a few facts about tobacco: • Tobacco comes in different forms….and all contain nicotine, the addictive substance. • Smoking forms of tobacco are beedis, cigarettes, cigars, chuttas, dhumti, pipe, hooklis, and hookah. • Smokeless forms of tobacco include chewing paan (betel quid) with zarda (tobacco), guthka, pan masala, manipuri tobacco, mawa, khaini, kaddi pudi, chewing tobacco leaves, mishri, gul, snuff, tobacco tooth paste and as tobacco water. Tobacco Facts • Tobacco is the leading cause of preventable death. • Each year tobacco kills 40,00,000 people. 2500 Indians die EVERYDAY due to tobacco related diseases. Deaths from tobacco use world wide are more than that from cocaine, heroin, alcohol, fires, accidents, murder, suicide, and AIDS COMBINED. • If you use tobacco, you are likely to die 15 years earlier. Tobacco Use: A Smart Guide 2 • Tobacco affects all the organs in the body from head to toe. -

Opioid Prescriber Reference Guide

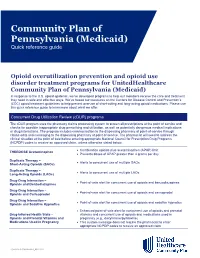

Community Plan of Pennsylvania (Medicaid) Quick reference guide Opioid overutilization prevention and opioid use disorder treatment programs for UnitedHealthcare Community Plan of Pennsylvania (Medicaid) In response to the U.S. opioid epidemic, we’ve developed programs to help our members receive the care and treatment they need in safe and effective ways. We’ve based our measures on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) opioid treatment guidelines to help prevent overuse of short-acting and long-acting opioid medications. Please use this quick reference guide to learn more about what we offer. Concurrent Drug Utilization Review (cDUR) programs The cDUR program uses the pharmacy claims processing system to screen all prescriptions at the point of service and checks for possible inappropriate drug prescribing and utilization, as well as potentially dangerous medical implications or drug interactions. The program includes communication to the dispensing pharmacy at point-of-service through claims edits and messaging to the dispensing pharmacy at point of service. The pharmacist will need to address the clinical situation at the point of sale before entering appropriate National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) codes to receive an approved claim, unless otherwise stated below. • Combination opioids plus acetaminophen (APAP) limit THERDOSE Acetaminophen • Prevents doses of APAP greater than 4 grams per day Duplicate Therapy – • Alerts to concurrent use of multiple SAOs Short-Acting Opioids (SAOs) Duplicate Therapy -

Does Areca Nut Use Lead to Dependence? Vivek Benegal ∗, Ravi P

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Drug and Alcohol Dependence 97 (2008) 114–121 Does areca nut use lead to dependence? Vivek Benegal ∗, Ravi P. Rajkumar, Kesavan Muralidharan Deaddiction Centre, Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore 560029, India Received 14 February 2007; received in revised form 24 March 2008; accepted 24 March 2008 Available online 19 May 2008 Abstract Background: The areca nut is consumed by approximately 10% of the world’s population, and its consumption is associated with long-term health risks, with or without tobacco additives. However, it is not known whether its use is associated with a dependence syndrome, as is seen with other psychoactive substances. Objective: To examine whether areca nut usage (with or without tobacco additives) could lead to the development of a dependence syndrome. Methods: Three groups: [a] persons using areca nut preparations without tobacco additives [n = 98]; [b] persons using areca nut preparations with tobacco additives [n = 44]; and [c] ‘Non-users’ were systematically assessed using a checklist for the use of areca or areca + tobacco products, patterns of use, presence of a dependence syndrome in users, features of stimulant withdrawal and desired/beneficial effects. -

Decision of the Minister of Health No. 1853515 on Approval of The

Unofficial Translation 22 Um Al- Friday 22 Rabea al-Awwal 1440 A.H - 30 Decisions & Laws Um Al-Qura Qura November 2018 Year 96 Year 96, Vol. 4755 [logo] Ministry of Health Decisions of the Ministry of Health Decision of the Minister of Health No. 1853515 on 29/12/ 1439 AH Approval on the Amendment of the Executive Regulation of Tobacco Control Law The Minister of Health, According to the authorities vested in him; After reviewing the Tobacco Law issued by the Royal Decree No. (M/56) on 28/07/1436 A.H; After reviewing Article 19 of Clause 1 of the Executive Regulation of Tobacco Control Law, which set forth that "The Ministry of Health reviews the Regulation one year from its enforcement and amends the same as it may requires". And as dictated by the public interest. Decided that: First: Approve the amendment to the Executive Regulation of Tobacco Control Law according to the form attached herewith: Second: This Regulation shall be published in the Official Gazette and on the Minister website and shall be put into force as of the date of its publication. Respectfully, Minister of Health Tawfiq bin Fawzran Al Rabiah Unofficial Translation 22 Um Al- Friday 22 Rabea al-Awwal 1440 A.H - 30 Decisions & Laws Um Al-Qura Qura November 2018 Year 96 Year 96, Vol. 4755 Executive Regulation of Tobacco Control Law Article 1: Law: This Law aims to control tobacco, by applying all the necessary procedures and steps in the State, society and individuals; reducing all forms of smoking habits at different ages. -

Quick Reference Guide: Opioid Overutilization Prevention And

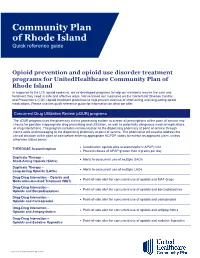

Community Plan of Rhode Island Quick reference guide Opioid prevention and opioid use disorder treatment programs for UnitedHealthcare Community Plan of Rhode Island In response to the U.S. opioid epidemic, we’ve developed programs to help our members receive the care and treatment they need in safe and effective ways. We’ve based our measures on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) opioid treatment guidelines to help prevent overuse of short-acting and long-acting opioid medications. Please use this quick reference guide for information on what we offer. Concurrent Drug Utilization Review (cDUR) programs The cDUR program uses the pharmacy claims processing system to screen all prescriptions at the point of service and checks for possible inappropriate drug prescribing and utilization, as well as potentially dangerous medical implications or drug interactions. The program includes communication to the dispensing pharmacy at point of service through claims edits and messaging to the dispensing pharmacy at point of service. The pharmacist will need to address the clinical situation at the point of sale before entering appropriate NCPDP codes to receive an approved claim, unless otherwise stated below. • Combination opioids plus acetaminophen (APAP) limit THERDOSE Acetaminophen • Prevents doses of APAP greater than 4 grams per day Duplicate Therapy – • Alerts to concurrent use of multiple SAOs Short-Acting Opioids (SAOs) Duplicate Therapy – • Alerts to concurrent use of multiple LAOs Long-Acting Opioids (LAOs) Drug-Drug -

Caitlyn D. Placek Curriculum Vitae July 2021

Caitlyn D. Placek Curriculum Vitae July 2021 Department of Anthropology Email: [email protected] Ball State University Phone: 765-285-1170 Muncie, IN 47306 Centerstone Research Institute Email: [email protected] Bloomington, IN 47403 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Medical Anthropology • Public Health • Global Health • Mixed Methods • Substance Use • Dietary Patterns • Maternal Health • Program Evaluation • South Asia EMPLOYMENT 2017-current Ball State University Assistant Professor of Biological Anthropology 2020-current Centerstone Research Institute Lead Program Evaluator 2016- 2017 National Institutes of Health Global Health Equity Scholars Postdoctoral Fellow, Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work, Florida International University AFFILIATIONS 2018-2020 Applied Anthropology Laboratory, Ball State University, Muncie, IN 2014- 2018 Public Health Research Institute of India, Mysore, Karnataka EDUCATION 2011- 2016 PhD, Anthropology, Washington State University 2009- 2011 MA, Anthropology, Washington State University 2004- 2008 BA, Anthropology, Eastern Kentucky University 2004- 2008 BS, Psychology, Eastern Kentucky University PUBLICATIONS Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles (undergraduate trainee co-authors underlined) 2021 29 Hlay J. K., Albert G., Batres C., Richardson G., Placek C., Arnocky S., Lieberman D., Hodges-Simeon, C. R. The evolution of disgust for pathogen detection and avoidance. Scientific Reports. 28 Placek C. D., Place J., Wies J. Reflections and challenges of pregnant and postpartum participant recruitment in the context of the opioid epidemic. Maternal and Child Health Caitlyn D. Placek 1 Journal, 1-5. 27 Placek C. D., Jaykrishna P., Srinivas V., Madhivanan P. M. Pregnancy fasting in Ramadan: Towards a Biocultural Framework. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 1-25. 26 Urassa M., Lawson D., Wamoyi J., Gurmu E., Gibson M., Madhivanan P., Placek C. -

Litigation Relevant to Regulation of Novel and Emerging Nicotine and Tobacco Products

Case summaries LITIGATION RELEVANT TO REGULATION OF NOVEL AND EMERGING NICOTINE AND TOBACCO PRODUCTS COMPARISONCASE SUMMARIES ACROSS JURISDICTIONS Benn McGrady and Kritika Khanijo A Case summaries B Case summaries LITIGATION RELEVANT TO REGULATION OF NOVEL AND EMERGING NICOTINE AND TOBACCO PRODUCTS CASE SUMMARIES C Litigation relevant to regulation of novel and emerging nicotine and tobacco products: case summaries ISBN 978-92-4-002418-2 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-002419-9 (print version) © World Health Organization 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules/). -

Community Information Drugs and Alcohol Factsheet 1 - Drugs and Drug Problems

Community Information Drugs and Alcohol Factsheet 1 - Drugs and Drug Problems Created by Foundation for Local Development Thailand www.fldasia.org February 2014 1 Drugs and Alcohol – Factsheet 1: Drugs and Drug Problems 2 COMMUNITY INFORMATION - Ethnic Peace Resources Project (www.eprpinformation.org) This Factsheet explains what drugs are, their effects and the problems they can cause for people. What is a drug? A drug is: “a chemical substance that affects the body in some way”. A drug can affect different parts of the body, such as the kidneys or liver or stomach or heart or the brain. There are many different types of drugs. Most drugs are made in laboratories, although some drugs come from plants. When they are made from plants they are usually called “herbs”. Different types of drugs Drugs are used to manage sickness (such as those that are used to treat malaria or infections) or improve health (such as vitamins or herbs). Drugs that are used to manage sickness or to improve health are also called medicines. The word “drug” is often used to describe those substances that are taken for recreation. That is, a substance taken not to fix illness or improve health, but because a person wants the effect the drug has on their mood, their level of alertness, and their perceptions. Some drugs that people use for recreation are legal (alcohol, betel nuts, tobacco). Other drugs that people use for recreation are illegal (opium, heroin, marijuana and amphetamines, yaba, ya-ice). Why do people use drugs? People use drugs for many reasons including: • Medical: Doctors prescribe drugs (medicines) for illnesses such as infections, malaria, diabetes. -

Oral Mucosal Lesions Associated with Use of Quid

C LINICAL P RACTICE Oral Mucosal Lesions Associated with Use of Quid • Sylvie Louise Avon, DMD, MSc • Abstract Quid is a mixture of substances that is placed in the mouth or actively chewed over an extended period, thus remaining in contact with the mucosa. It usually contains one or both of 2 basic ingredients, tobacco and areca nut. Betel quid or paan is a mixture of areca nut and slaked lime, to which tobacco can be added, all wrapped in a betel leaf. The specific components of this product vary between communities and individuals. The quid habit has a major social and cultural role in communities throughout the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and locations in the western Pacific. Following migration from these countries to North America, predominantly to inner city areas, the habit has remained prevalent among its practitioners. Many dentists are unaware of the prevalence of the quid or paan habit in the Asian patient population. The recognition of the role of such products in the development of oral precancer and cancer is of great importance to the dental practitioner. A variety of oral mucosal lesions and conditions have been reported in association with quid and tobacco use, and the association of these conditions with the development of oral cancer emphasizes the importance of education to limit the use of quid. In most cases, cessation of the habit produces improvement in mucosal lesions as well as in clinical symptoms. MeSH Key Words: areca/adverse effects; mouth neoplasms/chemically induced; precancerous conditions/chemically induced © J Can Dent Assoc 2004; 70(4):244–8 This article has been peer reviewed.