Don Burrows at 80 Years of Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Burrows Quartet

DON BURROWS QUARTET: SHOWCASE FOR A TALENTED NEWCOMER by Eric Myers _______________________________________________________________ The Don Burrows Quartet with James Morrison The Rothbury Estate, Pokolbin Sydney Morning Herald, April 8, 1980 _______________________________________________________________ t is difficult to imagine a more pleasant afternoon than one spent on the Rothbury Estate, with the sun shining, the wine flowing, and jazz provided I by Don Burrows, George Golla and their colleagues. At this concert, Burrows (clarinet, flute and alto saxophone) and Golla (guitar) gave a roaring display of the swinging, mainstream jazz that is appealing and relaxing for so many people. In their playing, there are few signs of the atonality, chromaticism and dissonance which characterise much contemporary modern jazz, and this perhaps explains their great popularity with middle-of-the-road jazz lovers. Don Burrows (left, flute) and George Golla (guitar): a roaring display of the swinging, mainstream jazz that is appealing and relaxing for so many people…PHOTO COURTESY JAZZ AUSTRALIA Tony Ansell, as always, played the keyboards with high energy and vitality. For many years now, he has been astounding orthodox pianists by playing the keyboard bass with his left hand, while producing brilliant accompaniment and solos on electric piano or synthesiser with his right hand —in effect, playing an instrument with each hand, and enabling either to function independently of the other. I was often surprised to hear the drummer, Stuart Livingston, -

OBITUARY: JOHN SANGSTER 1928-1995 by Bruce Johnson

OBITUARY: JOHN SANGSTER 1928-1995 by Bruce Johnson _________________________________________________________ ohn Grant Sangster, musician/composer, was born 17 November 1928 in Melbourne, only child of John Sangster and Isabella (née Davidson, then J Pringle by first marriage). He attended Sandringham (1933), then Vermont Primary Schools, and Box Hill High School. Self-taught on trombone then cornet, learning from recordings with friend Sid Bridle, with whom he formed a band. Sangster on cornet: self-taught first on trombone, then cornet… PHOTO COURTESY AUSTRALIAN JAZZ MUSEUM Isabella’s hostility towards John and his jazz activities came to a head on 21 September 1946, when she withdrew permission for him to attend a jazz event; in the ensuing confrontation he killed her with an axe but was acquitted of both murder and manslaughter. In December 1946 he attended the first Australian Jazz Convention (AC) in Melbourne, December 1946, and at the third in 1948 he won an award from Graeme Bell as ‘the most promising player’. He first recorded December 30th, and participated in the traditional jazz scene, including through the community centred on the house of Alan Watson in Rockley Road, South Yarra. 1 He married Shirley Drew 18 November 1949. In 1950 recorded (drums) with Roger, then Graeme Bell, and was invited to join Graeme’s band on drums for their second international tour (26 October 1950 to 15 April 1952). During this tour Sangster recorded his first composition, and encountered Kenny Graham’s Afro-Cubists and Johnny Dankworth, which broadened his stylistic interests. Graeme Bell invited Sangster to join Graeme’s band on drums for their second international tour, October 1950 to April 1952.. -

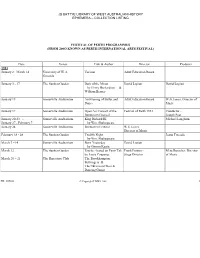

Festival of Perth Programmes (From 2000 Known As Perth International Arts Festival)

FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 2000 KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer Principals 1980 1980 Festival of Perth Festival Programme 14 Feb-18 Mar 1980 Various Festival at Bunbury WA Arts Council & City of Bunbury Feb – Mar 1980 Various PBS Festival of Perth Festival of Perth 1980 Spike Milligan, Tim Theatre Brooke-Taylor, Cathy Downes 17 Feb-16 Mar 1980 Churchill Gallery Lee Musgrave Paintings on Perspex 22 Feb-15 Mar 1980 Perth Concert Hall The Festival Club Bank of NSW Various 22 Feb 1980 Supreme Court Opening Concert Captain Colin Harper David Hawkes Compere Various Bands, Denis Gardens Walter Singer 23 Feb 1980 St George’s Cathedral A Celebration Festival of Perth 1980 The Very Reverend Cathedral Choir, David Robarts Address Cathedral Bellringers, Arensky Quartet, Anthony Howes 23 Feb 1980 Perth Concert Hall 20th Century Music Festival of Perth 1980, David Measham WA Symphony ABC Conductor Orchestra, Ashley Arbuckle Violin 23 Feb – 4 Mar 1980 Dolphin Theatre Richard Stilgoe Richard Stilgoe Take Me to Your Lieder 23 Feb-15 Mar 1980 Dolphin Theatre Northern Drift Alfred Bradley Henry Livings, Alan Glasgow 24 Feb 1980 Supreme Court Tops of the Pops for Festival of Perth 1980, Harry Bluck Various groups and Gardens ‘80 R & I Bank, SGIO artists 24 Feb, 2 Mar 1980 Art Gallery of WA The Arensky Piano Trio Festival of Perth 1980, Jack Harrison Clarinet playing Brahms Alcoa of Aust Ltd 25 Feb 1980 Perth Entertainment Ballroom Dance Festival of Perth 1980 Sam Gilkison Various dancing PR10960/1980-1989 -

Joseph Tawadros

RIVERSIDE THEATRES PRESENTS JOSEPH TAWADROS Riverside presents City of Holroyd Brass Band QUARTEand PackeminT Productions MUSIC SUNDAY 28 FEB AT 3PM boundaries; a migrant success story BIOGRAPHIES founded on breathtaking talent and a larrikin sense of humour. JOSEPH Joseph has toured extensively headlining in Europe, America, Asia and the Middle TAWADROS East and has collaborated with artists Oud such as tabla master Zakir Hussain, Despite being just 32, Joseph Tawadros has sarangi master Sultan Khan, Banjo already achieved great success. His three maestro Bela Fleck, John Abercrombie, recent albums, Permission to Evaporate, Jack DeJohnette, Christian McBride, Mike Chameleons of the White Shadows and Stern, Richard Bona, Ivry Gitlis, Neil Finn Concerto of the Greater Sea took out ARIAs and Katie Noonan. He has also had guest for Best World Music Album. Every single appearances with the Sydney, Adelaide and one of his albums has been nominated Perth Symphony Orchestras. for ARIA recognition. He blends and blurs Joseph is also recognised for his mastery musical tradition while crossing genres and of the instrument in the Arab world. He has the end result is magical. He has recorded, been invited to adjudicate the Damascus composed for and performed with many of International Oud Competition in 2009, to the biggest international jazz and classical perform at Istanbul’s inaugural Oud Festival artists. Joseph continues to create modern in 2010 and at the Institut du Monde Arabe, platforms for one of the world’s oldest Paris in 2013. instruments, remaining true to its soul while pairing it with unlikely accents. 2015 saw a national tour with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, as well Joseph is the recipient of an Order of as performances at Melbourne Recital Australia 2016, winner of the 2014 NSW Centre, Elder Hall (Adelaide) and the highly Premier’s Multicultural Award for Arts and anticipated release of his twelfth album, Culture, and finalist for Young Australian of Truth Seekers, Lovers and Warriors for ABC the Year in 2013. -

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A. -

The Norfolk ISLANDER the World of Norfolk’S Community Newspaper for More Than 44 Years

The Norfolk ISLANDER The World of Norfolk’s Community Newspaper for more than 44 Years FOUNDED 1965 Successors to - The Norfolk Island Pioneer c. 1885 The Weekly News c 1932 : The Norfolk Island Monthly News c. 1933 The N.I. Times c. 1935 : Norfolk Island Weekly c. 1943 : N.I.N.E. c. 1949 : W.I.N. c. 1951 : Norfolk News c. 1965 Volume 44, No. 35 SATURDAY, 5th SEPTEMBER 2009 Price $2.75 incl GST Dr Chistophe Sand from New Caledonia What Is A Father? visited Kingston & Arthur’s Vale Historic Area on Thursday and Friday last week. A father is wisdom, love, and understanding; he is the Dr Sand is the ICOMOS technical expert firm voice, the helping hand in time of trouble. who is preparing a report on the site as part of ICOMOS’s evaluation of the He is the family’s trust and hope, its guard and guide, the world heritage nomination. strength of its ideals. The ICOMOS evaluation will eventually be presented to the World Heritage A father is encouragement and honour, and justice Committee with a recommendation tempered with humour. regarding the listing. Next week’s KAVHA column will He is a speaker or a listener, according to your needs. contain more information on the visit and He is always there when you need him, because he’s the next steps in the process. finest of fathers -- because he is YOU ! Our photo shows local community members who attended an afternoon tea Tell Dad you love him this Fathers Day - in the Annexe of No. -

Don Banks, Australian Composer

Don Banks, Australian Composer: Eleven Sketches Graham Hair Southern Voices ISBN 1–876463–09–0 First published in 2007 by Southern Voices 38 Diamond Street Amaroo, ACT 2914 AUSTRALIA Southern Voices Editorial Board: Professor Graham Hair, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom Ms Robyn Holmes, Curator of Music, National Library of Australia Professor Margaret Kartomi, Monash University Dr Jonathan Powles, Australian National University Dr Martin Wesley-Smith, formerly Senior Lecturer, Sydney Conservatorium of Music Distributed by The Australian Music Centre, trading asSounds Australian PO Box N690 The Rocks Sydney, NSW 2000 AUSTRALIA tel +(612) 9247 - 4677 fax +(612) 9241 - 2873 email [email protected] website www.amcoz.com.au/amc Copyright © Graham Hair, 2007 This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Enquiries to be made to the publisher. Copying for educational purposes Where copies of part or the whole of the book are made under section 53B or 53D of the Act, the law requires that records of such copying be kept. In such cases the copyright owner is entitled to claim payment. ISBN 1–876463–09–0 Printed in Australia by QPrint Pty Ltd, Canberra City, ACT 2600 and in the UK by Garthland Design and Print, Glasgow, G51 2RL Acknowledgements Extracts from the scores by Don Banks are reproduced by permission of Mrs Val Banks and Mrs Karen Sutcliffe. -

Keith Stirling: an Introduction to His Life and Examination of His Music

KEITH STIRLING: AN INTRODUCTION TO HIS LIFE AND EXAMINATION OF HIS MUSIC Brook Ayrton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of M.Mus. (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2011 1 I Brook Ayrton declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Signed:…………………………………………………………………………… Date:………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Abstract This study introduces the life and examines the music of Australian jazz trumpeter Keith Stirling (1938-2003). The paper discusses the importance and position of Stirling in the jazz culture of Australian music, introducing key concepts that were influential not only to the development of Australian jazz but also in his life. Subsequently, a discussion of Stirling’s metaphoric tendencies provides an understanding of his philosophical perspectives toward improvisation as an art form. Thereafter, a discourse of the research methodology that was used and the resources that were collected throughout the study introduce a control group of transcriptions. These transcriptions provide an origin of phrases with which to discuss aspects of Stirling’s improvisational style. Instrumental approaches and harmonic concepts are then discussed and exemplified through the analysis of the transcribed phrases. Stirling’s instrumental techniques and harmonic concepts are examined by means of his own and student’s hand written notes and quotes from lesson recordings that took place in the early 1980s. 3 Acknowledgements Many thanks go to the following individuals for their thoughts and reflections on matters in the study and their remembrance of a time when Australian jazz music was prolific in the popular culture of this country. -

Seeking an Australian Musical Identity a Personal Perspective by Mandy Stefanakis

FEATURE ARTICLE Seeking an Australian Musical Identity A Personal Perspective by Mandy Stefanakis That there is a great diversity of music composed in Australia Most countries have a definable musical sound in a number is obvious, however identifying a uniquely Australian sound of musical styles. For example George Gershwin, Aaron is much harder. Copland, Duke Ellington and Robert Johnson represent different styles, but all have composed music which is Traditional Aboriginal music defines very purely the lifestyle undeniably American. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra and environment of Aboriginal people. Traditional Aboriginal sounds like an American orchestra, even when it’s playing music has unique instruments. The didgeridoo is unlike any Wagner. And speaking of Wagner, and Bach and Schubert . other instrument on earth both in structure and function. It is . even the new German techno rock, though light years away a perfect vehicle for the expression of the hypnotic, cyclic, from the classics of German composers is still distinctively spacious, rhythmic, spiritual elements of traditional German. Elgar, Vaughan-Williams and The Beatles are Aboriginal culture and habitat. essentially English. The Cranberries and The Chieftains are passionately Irish, Vivaldi and Puccini elaborately Italian and Other Australians have quite diverse heritages and we could also wax lyrical about the unique characteristics of cultures. Many Australian musicians have tried to capture music in Asia, South America and Africa. The explanation for the essence of Australianness, often drawing on the the unique sounds of some of these countries, lies to a certain traditions of Aboriginal music for their inspiration. Some extent in the richness and length of their folk traditions. -

University of Wollongong Campus News 12 September 1989

THE UniVERSITY OF WOLLOnQOMQ CAMPUS INEWS Distributed each Tuesday Deadline for copy noon Monday Editor: George Wilson, TeL (042) 27 0926 of previous week (042) 28 6691 12 September 1989 Director of Statistical Consulting Dr Ken Russell takes up his appointment Dr Ken Russell took up the position of Director of Statistical Consulting within the Mathematics Department at the end of July. He took over from Dr Ross Sparks, who acted as Director for the first seven months of 1989. In Session 1 projects were undertaken for researchers from all faculties of the university and members of the Mathematics Depart ment provided assistance with a wide range of statistical and mathematical problems. The consulting service is available to all staff of the university and to research students; students must be accompanied by their supervisors on their first consulta tions. The service is free for staff and students working on investigations not receiving external funding. Investigators with such funding are normally expected to have included provision for statistical assistance in their funding submis sions and will be charged for statistical services. Commer cial rates will be charged to clients outside the university. Further information about the consulting service will appear in a more detailed article in a future issue of Campus Nexos. Near the middle of Session 2 a general information Dr Ken Russell lectiu-e on the consulting service, open to all members of the university, will be given, while more specific subject- orientated lectures will be offered to individual departments People consulting another member of the Mathematics in due course. -

26 November 2007 Federation Square Melbourne

Finalist exhibition 12 – 26 November 2007 Federation Square Melbourne Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 fi nalists / Brenton Broadstock / Paul Grabowsky / David Jones / Paul Kelly / Richard Mills Outstanding Musicians Award fi nalists / Clare Bowditch / David Chisholm / The Cat Empire / Luke Howard and Leonard Grigoryan / Cameron Hill / Andrea Keller / Genevieve Lacey / Stephen Magnusson / Geoffrey Morris / Flinders Quartet Development Award fi nalists / Sam Anning / Sophie Brous / Aura Go / Julian Langdon / Tristram Williams The Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 The free public exhibition of fi nalists will be catalogue provides a review of the fi nalists held in the Atrium at Federation Square in the following award categories: between 12 – 26 November 2007. Visitors can read about each fi nalist and listen to examples / Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 of their music. / Outstanding Musicians Award For further information on the Melbourne Prize / Development Award Trust and Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 please visit www.melbourneprizetrust.org or call 03 9650 8800. The Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 is made possible by the support of our partners and patrons. The Melbourne Prize Trust would like to thank all partners for their generosity. Government Partner Founding Partners Patrons Diana Gibson AO Megg Evans Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 Partners Venue & Exhibition Partner Exhibition Design Exhibition Construction Digital Printing & Banners Exhibition Photography Exhibition Consultants Coleby Consulting Audio Equipment PartnerMedia Communications Professional Services Print Partner Winners Trophies Website Fundere Foundry The Melbourne Prize for Music 2007 celebrates excellence and talent in music and demonstrates the value our community places on its creative resources. With the generous support of all our partners, we have been able to recognise and reward the abundant and diverse musical talent we have in Victoria and make this accessible to the public. -

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 3, May 2, 1988 Writer & Editor: Eric Myers, National Jazz Co-Ordinator ______

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 3, May 2, 1988 Writer & editor: Eric Myers, National Jazz Co-ordinator ________________________________________________________ Visit of the Australian Jazz Orchestra to the United States. In a two-weeks visit to the United States, from April 5-19, the AJO played to open-air audiences for three days at the Houston International Festival, in jazz clubs for one night in Chicago (The Jazz Showcase), San Francisco (Kimball's) and Los Angeles (Catalina Bar & Grill), in a New York jazz club (Carlos I) for three nights, and to a concert hall audience of over 400 at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. A shot of the Australian Jazz Orchestra, which appeared in The Australian newspaper on December 11, 1987. Four musicians at the back are L-R, James Morrison, Paul Grabowsky, Dale Barlow, Bernie McGann. Middle row, L-R, Gary Costello, Doug DeVries, Bob Venier, Bob Bertles, Alan Turnbull, Don Burrows, Warwick Alder. Front row, crouching, L-R, Peter Brendlé, Eric Myers. This does not include the trombonist Dave Panichi who joined the band for the US tour… PHOTO CREDIT BRANCO GAICA 1 The band included 12 musicians: Warwick Alder (trt & flugel), Bob Venier (trt & flugel), James Morrison (tromb, trt, tuba & euphonium), Dave Panichi (tromb & flugbn), Bob Bertles (alto, baritone & flute), Bernie McGann (alto), Dale Barlow (sop & tenor), Don Burrows (flutes & baritone), Paul Grabowsky (pno), Doug de Vries (gtr), Gary Costello (bass) and Alan Turnbull (drs). Trombonist Dave Panichi, who joined the AJO for the US tour… As I was able to hear every performance of the AJO in the US, I can vouch for the fact that the band played with absolute brilliance; the players generally played longer solos than they did with the AJO in Australia, and pushed themselves way beyond their normal limits.