Keith Stirling: an Introduction to His Life and Examination of His Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vivid Sydney Media Coverage 1 April-24 May

Vivid Sydney media coverage 1 April-24 May 24/05/2009 Festival sets the city aglow Clip Ref: 00051767088 Sunday Telegraph, 24/05/09, General News, Page 2 391 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes A SPECTACLE of light, sound and creativity is about to showcase Sydney to the world. Vivid Sydney, developed by Events NSW and City of Sydney Council, starts on Tuesday when the city comes alive with the biggest international music and light extravaganza in the southern hemisphere. Keywords: Brian(1), Circular Quay(1), creative(3), Eno(2), festival(3), Fire Water(1), House(4), Light Walk(3), Luminous(2), Observatory Hill(1), Opera(4), Smart Light(1), Sydney(15), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Looking on the bright side Clip Ref: 00051771227 Sunday Herald Sun, 24/05/09, Escape, Page 31 419 words By: Nicky Park Type: Feature Photo: Yes As I sip on a sparkling Lindauer Bitt from New Zealand, my eyes are drawn to her cleavage. I m up on the 32nd floor of the Intercontinental in Sydney enjoying the harbour views, dominated by the sails of the Opera House. Keywords: 77 Million Paintings(1), Brian(1), Eno(5), Festival(8), House(5), Opera(5), Smart Light(1), sydney(10), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Glow with the flow Clip Ref: 00051766352 Sun Herald, 24/05/09, S-Diary, Page 11 54 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes How many festivals does it take to change a coloured light bulb? On Tuesday night Brian Eno turns on the pretty lights for the three-week Vivic Festival. -

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

Until the Late Twentieth Century, the Historiography and Analysis of Jazz Were Centered

2 Diasporic Jazz Abstract: Until the late twentieth century, the historiography and analysis of jazz were centered on the US to the almost complete exclusion of any other region. This was largely driven by the assumption that only the “authentic” version of the music, as represented in its country of origin, was of aesthetic and historical interest in the jazz narrative; that the forms that emerged in other countries were simply rather pallid and enervated echoes of the “real thing.” With the growth of the New Jazz Studies, it has been increasingly understood that diasporic jazz has its own integrity, as well as holding valuable lessons in the processes of cultural globalization and diffusion and syncretism between musics of the supposed center and peripheries. This has been accompanied by challenges to the criterion of place- and race-based authenticity as a way of assessing the value of popular music forms in general. As the prototype for the globalization of popular music, diasporic jazz provides a richly instructive template for the study of the history of modernity as played out musically. The vigor and international impact of Australian jazz provide an instructive case study in the articulation and exemplification of these dynamics. Section 1 Page 1 of 19 2 Diasporic Jazz Running Head Right-hand: Diasporic Jazz Running Head Left-hand: Bruce Johnson 2 Diasporic Jazz Bruce Johnson New Jazz Studies and Diaspora The driving premise of this chapter is that “jazz was not ‘invented’ and then exported. It was invented in the process of being disseminated” (Johnson 2002a, 39). With the added impetus of the New Jazz Studies (NJS), it is now unnecessary to argue that point at length. -

Marc Brennan Thesis

Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia Marc Brennan, BA (Hons) Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre (CIRAC) Thesis Submitted for the Completion of Doctor of Philosophy (Creative Industries), 2005 Writing to Reach You Keywords Journalism, Performance, Readerships, Music, Consumers, Frameworks, Publishing, Dialogue, Genre, Branding Consumption, Production, Internet, Customisation, Personalisation, Fragmentation Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia The music press and music journalism are rarely subjected to substantial academic investigation. Analysis of journalism often focuses on the production of news across various platforms to understand the nature of politics and public debate in the contemporary era. But it is not possible, nor is it necessary, to analyse all emerging forms of journalism in the same way for they usually serve quite different purposes. Music journalism, for example, offers consumer guidance based on the creation and maintenance of a relationship between reader and writer. By focusing on the changing aspects of this relationship, an analysis of music journalism gives us an understanding of the changing nature of media production, media texts and media readerships. Music journalism is dialogue. It is a dialogue produced within particular critical frameworks that speak to different readers of the music press in different ways. These frameworks are continually evolving and reflect the broader social trajectory in which music journalism operates. Importantly, the evolving nature of music journalism reveals much about the changing consumption of popular music. Different types of consumers respond to different types of guidance that employ a variety of critical approaches. -

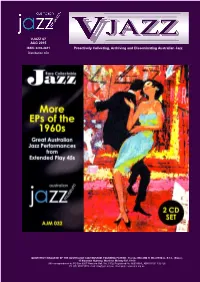

VJAZZ 67 AUG 2015 Proactively Collecting, Archiving and Disseminating Australian Jazz

VJAZZ 67 AUG 2015 ISSN: 2203-4811 Proactively Collecting, Archiving and Disseminating Australian Jazz Distribution 650 QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE AUSTRALIAN JAZZ MUSEUM. FOUNDING PATRON: The late WILLIAM H. MILLER M.A., B.C.L. (Oxon.) 15 Mountain Highway, Wantirna Melway Ref. 63 C8 (All correspondence to: PO Box 6007 Wantirna Mall, Vic. 3152) Registered No: A0033964L ABN 53 531 132 426 Ph (03) 9800 5535 email: [email protected]. Web page: www.ajm.org.au VJAZZ 67 Page 2 Letters to the Editor Contents 02 Letters to the Editor Dear Editor, 03 He’s the Drummer Man in the Band I am really overwhelmed about both articles, (Vjazz 66) the layout of it and how By Bill Brown you appreciate Coco Schumann. He will be very happy to read that he is not for- 04 The Museum’s 100-year-old Recordings gotten Down Under. As soon as I have the printed version I will forward it to him. I By Ken Simpson-Bull didn't know that you will use the photo with us, so I was flabbergasted to see this 06 Research Review - A Searing Sound young couple with Coco on p.7 :-) By John Kennedy OAM Well done, you did a great job, Ralph. 07 News from the Collection Jazzily By Ralph Powell Detlef 08 Visitors to the Archive 10 Instrument of Choice Dear Editor Oh So Beautiful Your members might be interested to know that Jack O’Hagan’s story and music 11 Two Studies in Brown is being brought back into focus. By Bill Brown I am near to completion of my grandfather Jack O’Hagan’s biography. -

Don Burrows Quartet

DON BURROWS QUARTET: SHOWCASE FOR A TALENTED NEWCOMER by Eric Myers _______________________________________________________________ The Don Burrows Quartet with James Morrison The Rothbury Estate, Pokolbin Sydney Morning Herald, April 8, 1980 _______________________________________________________________ t is difficult to imagine a more pleasant afternoon than one spent on the Rothbury Estate, with the sun shining, the wine flowing, and jazz provided I by Don Burrows, George Golla and their colleagues. At this concert, Burrows (clarinet, flute and alto saxophone) and Golla (guitar) gave a roaring display of the swinging, mainstream jazz that is appealing and relaxing for so many people. In their playing, there are few signs of the atonality, chromaticism and dissonance which characterise much contemporary modern jazz, and this perhaps explains their great popularity with middle-of-the-road jazz lovers. Don Burrows (left, flute) and George Golla (guitar): a roaring display of the swinging, mainstream jazz that is appealing and relaxing for so many people…PHOTO COURTESY JAZZ AUSTRALIA Tony Ansell, as always, played the keyboards with high energy and vitality. For many years now, he has been astounding orthodox pianists by playing the keyboard bass with his left hand, while producing brilliant accompaniment and solos on electric piano or synthesiser with his right hand —in effect, playing an instrument with each hand, and enabling either to function independently of the other. I was often surprised to hear the drummer, Stuart Livingston, -

January 2021 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

Bluesletter J W B S . Nick Vigarino Still Rocks the House! Live at the US Embassy: Blues Happy Hour Remembering Jimmy Holden LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Hi Blues Fans, Proud Recipient of a 2009 I’m opening my letter with Keeping the Blues Alive Award another remembrance of another friend lost in our 2021 OFFICERS blues community. I have had to President, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org do this a few too many times Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected]@wablues.org lately and it is a reminder of Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected]@wablues.org how fragile life is and how Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected]@wablues.org important it is to live every day Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected]@wablues.org and make as many memories as you can. 2021 DIRECTORS Jimmy Holden passed away recently. I know there are many music Music Director, Open [email protected]@wablues.org fans who have great memories of Jimmy and his many performances Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected]@wablues.org and he touched many hearts with warmth, humor and melody. I will Education, Open [email protected]@wablues.org miss Jimmy for all of his wonderful stories about his travels. He Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected]@wablues.org traveled far and wide and we shared experiences we had both had Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org in multiple different localities around the world. Our conversations Advertising, Open [email protected]@wablues.org often lead to stories about adventures in Hong Kong, Thailand and other exotic places. -

![JOHN SANGSTER: THREE NEW ALBUMS Reviewed by Eric Myers ______[This Review Appeared in the July, 1981 Edition of Penthouse Magazine]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3091/john-sangster-three-new-albums-reviewed-by-eric-myers-this-review-appeared-in-the-july-1981-edition-of-penthouse-magazine-413091.webp)

JOHN SANGSTER: THREE NEW ALBUMS Reviewed by Eric Myers ______[This Review Appeared in the July, 1981 Edition of Penthouse Magazine]

JOHN SANGSTER: THREE NEW ALBUMS Reviewed by Eric Myers _______________________________________________________________ [This review appeared in the July, 1981 edition of Penthouse magazine] ith the simultaneous release of a double album and two single albums of original music recently, John Sangster confirms there is W probably no more fertile composer in Australian jazz than himself. The double album, Uttered Nonsense: The Owl and the Pussycat (Rain Forest Records) is the first Sangster work to be released since he completed his monumental jazz suites inspired by the fantasy world of J R R Tolkien — an enormous project which required ten LP records to encompass the composer's flights of imagination. Uttered Nonsense features music accompanying eight nonsense poems written by the 19th Century eccentric Edward Lear and narrated by Ivan Smith, and also various instrumental pieces inspired by Lear. The great merit of John Sangster's music is that it provides sympathetic contexts for many of the great players in Australian jazz to express themselves freely. There are some 20 musicians on this album, including Bob Barnard (cornet), Bob McIvor (trombone), John McCarthy (clarinet), Graeme Lyall (clarinet and 1 saxophones), Tony Gould (piano), Jim Kelly (guitar) and, of course, Sangster himself, playing vibraphone, marimba, glockenspiel, swanne-whistle, piano, celeste and percussions. One of the most attractive pieces is the title-track, The Owl and the Pussycat, Lear's best-known work. Ivan Smith's narration is followed by Jim Kelly's improvisation of some beautiful guitar lines over gently played ensemble work. Forced to categorise Sangster's music, one might call it a superior form of dixieland or, as the Sydney musician Michael Kenny once described it, "cosmic dixieland". -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS and CONTENT LIST - Content for Broadcast on Your Station

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Content for broadcast on your station May 2019 All times AEST/AEDT CRN PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Table of contents FLAGSHIP PROGRAMMING Beyond Zero 9 Phil Ackman Current Affairs 19 National Features and Documentary Bluesbeat 9 Playback 19 Series 1 Cinemascape 9 Pop Heads Hour of Power 19 National Radio News 1 Concert Hour 9 Pregnancy, Birth and Beyond 20 Good Morning Country 1 Contact! 10 Primary Perspectives 20 The Wire 1 Countryfolk Around Australia 10 Radio-Active 20 SHORT PROGRAMS / DROP-IN Dads on the Air 10 Real World Gardener 20 CONTENT Definition Radio 10 Roots’n’Reggae Show 21 BBC World News 2 Democracy Now! 11 Saturday Breakfast 21 Daily Interview 2 Diffusion 11 Service Voices 21 Extras 1 & 2 2 Dirt Music 11 Spectrum 21 Inside Motorsport 2 Earth Matters 11 Spotlight 22 Jumping Jellybeans 3 Fair Comment 12 Stick Together 22 More Civil Societies 3 FiERCE 12 Subsequence 22 Overdrive News 3 Fine Music Live 12 Tecka’s Rock & Blues Show 22 QNN | Q-mmunity Network News 3 Global Village 12 The AFL Multicultural Show 23 Recorded Live 4 Heard it Through the Grapevine 13 The Bohemian Beat 23 Regional Voices 4 Hit Parade of Yesterday 14 The Breeze 23 Rural Livestock 4 Hot, Sweet & Jazzy 14 The Folk Show 23 Rural News 4 In a Sentimental Mood 14 The Fourth Estate 24 RECENT EXTRAS Indij Hip Hop Show 14 The Phantom Dancer 24 New Shoots 5 It’s Time 15 The Tiki Lounge Remix 24 The Good Life: Season 2 5 Jailbreak 15 The Why Factor 24 City Road 5 Jam Pakt 15 Think: Stories and Ideas 25 Marysville -

MOONTRANE PROVIDES SOME JAZZ ACTION by Eric Myers Jazz Action S

MOONTRANE PROVIDES SOME JAZZ ACTION by Eric Myers ______________________________________________________________ Jazz Action Society concert February 6, 1980, Musicians’ Club Encore Magazine, March, 1980 ______________________________________________________________ his concert was opened by two sets provided by the John Leslie Trio, including the leader on vibraharp, Gary Norman (electric guitar) and T Richard Ochalski (acoustic bass). Their music consisted of jazz and popular music standards in swinging 4/4 tempo: Jerome Kern's All The Things You Are, Horace Silver's Opus de Funk and Doodlin', Oliver Nelson's Stolen Moments, Clifford Brown's Joy Spring etc. Richard Ochalski, bassist with the John Leslie Trio… These sets were mainly distinguished by the fluent playing of Gary Norman, who appears to be an impressive new addition to the ranks of Sydney jazz guitarists. He swings easily, and employs a nice vibrato at the end of his long notes, enabling the guitar to sing, in a style not unlike that of the American guitarist Larry Carlton. There was a hint of unease in John Leslie's playing, which appeared a little hurried and up on the beat, although this tendency was less apparent by the closing stages of the trio's second set. Inevitable sameness: The music played by this group suffered from an inevitable sameness, as the format adopted for each tune was, if I remember correctly, exactly the same: statement of theme, a solo from each player, then return to the theme. Bass solos are a welcome contrast, but in every tune? Without a drummer to provide some rhythmic drive and a few extra colours, this group played a little too long, which meant that Bob Bertles' Moontrane 1 was not able to start until 10.30pm. -

ON ARTHUR JAMES RECEIVING the OAM by John Sangster

ON ARTHUR JAMES RECEIVING THE OAM by John Sangster _________________________________________________________ [This article by John Sangster appeared in the Jan/Feb 1994 edition of Jazzchord. In the 1994 Australia Day honours list there was one award for a member of the jazz community. Arthur James, the manager of the famous El Rocco, which operated as a jazz cellar in Sydney’s Kings Cross circa 1957 to 1969, received the OAM, “for exceptional service to the development of Australian jazz.” The testimonies of various leading musicians who played at the El Rocco were enough to secure the honour. In August, 1989, John Sangster wrote the following regarding Arthur James’s role in the development of jazz in Sydney. The origin of Sangster’s statement is unknown.] ’ve been lucky enough to have spent the first half of my life as a musician in the ‘trad’ or Dixieland’ idiom, where the emphasis is on dancing and having a good I time, and generally whooping it up; and the second half of my life in the ‘modern’ jazz framework, where the audiences prefer to sit and actually listen to the musicians. The ten years I spent playing with, and composing for, the various groups at Arthur James’s El Rocco jazz club were, I think, highly significant, not only for my own musical development, but for a host of other ‘modern’ jazz players and composers. Arthur James… PHOTO CREDIT BRUCE JOHNSON It’s no exaggeration to say that Arthur James’s patience, encouragement and enthusiasm, against very heavy odds, right through the 60s, was directly responsible for the emergence of such overseas ‘ambassadors’ for Australian jazz music as Don Burrows, whose quartet I was a founding member of, the Mike Nock Trio, Judy 1 Bailey (with whom I also performed, and still, on occasions, do) and many others who are now ‘household names’.