Communicating Artistry Through Gesture by Legendary Australian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Burrows Quartet

DON BURROWS QUARTET: SHOWCASE FOR A TALENTED NEWCOMER by Eric Myers _______________________________________________________________ The Don Burrows Quartet with James Morrison The Rothbury Estate, Pokolbin Sydney Morning Herald, April 8, 1980 _______________________________________________________________ t is difficult to imagine a more pleasant afternoon than one spent on the Rothbury Estate, with the sun shining, the wine flowing, and jazz provided I by Don Burrows, George Golla and their colleagues. At this concert, Burrows (clarinet, flute and alto saxophone) and Golla (guitar) gave a roaring display of the swinging, mainstream jazz that is appealing and relaxing for so many people. In their playing, there are few signs of the atonality, chromaticism and dissonance which characterise much contemporary modern jazz, and this perhaps explains their great popularity with middle-of-the-road jazz lovers. Don Burrows (left, flute) and George Golla (guitar): a roaring display of the swinging, mainstream jazz that is appealing and relaxing for so many people…PHOTO COURTESY JAZZ AUSTRALIA Tony Ansell, as always, played the keyboards with high energy and vitality. For many years now, he has been astounding orthodox pianists by playing the keyboard bass with his left hand, while producing brilliant accompaniment and solos on electric piano or synthesiser with his right hand —in effect, playing an instrument with each hand, and enabling either to function independently of the other. I was often surprised to hear the drummer, Stuart Livingston, -

Sean Mcculloch – Lead Vocals Daniel Gailey – Guitar, Backing Vocals Bryce Kelly – Bass, Backing Vocals Lee Humarian – Drums

Sean McCulloch – Lead Vocals Daniel Gailey – Guitar, Backing Vocals Bryce Kelly – Bass, Backing Vocals Lee Humarian – Drums Utter and complete reinvention isn’t the only way to destroy boundaries. Oftentimes, the most invigorating renewal in any particular community comes not from a generation’s desperate search for some sort of unrealized frontier, but from a reverence for the strength of its foundation. The steadfast metal fury of PHINEHAS is focused, deliberate, and unashamed. Across three albums and two EPs, the Southern California quartet has proven to be both herald of the genre’s future and keeper of its glorious past. The New Wave Of American Metal defined by the likes of As I Lay Dying, Shadows Fall, Unearth, All That Remains, Bleeding Through, and likeminded bands on the Ozzfest stage and on the covers of heavy metal publications has found a new heir in PHINEHAS. Even as the NWOAM owed a sizeable debt to Europe’s At The Gates and In Flames and North America’s Integrity and Coalesce, PHINEHAS grab the torch from the generation just before them. The four men of mayhem find themselves increasingly celebrated by fans, critics, and contemporaries, due to their pulse-pounding brutality. Make no mistake: PHINEHAS is not a simple throwback. PHINEHAS is a distillation of everything that has made the genre great since bands first discovered the brilliant results of combining heavy metal’s technical skill with hardcore punk’s impassioned fury. SEAN MCCULLOCH has poured his heart out through his throat with decisive power, honest reflections on faith and doubt, and down-to-earth charm since 2007. -

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

Fne Music Magazne

February 2013 MAGAZINE VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY The Mystery of Music CORRALLING THE MASSES Sydney Philharmonia Choirs THE MUSIC- MATH MYTH Simon Tedeschi MASTER OF MODERNISM - Elliott Carter BIRTH OF AN OPERA Un Ballo in Maschera FROM THE ROYAL OPERA LA BOHEME MARCH 1, 2, 3 & 6 www.palaceoperaandballet.com.au CONTENTS EDITOR’S DESK In our cover story there’s a classic master-meets- Vol 40 No 2 apprentice moment as Robert Clark endeavours 4 COVER STORY to find some insights into how the great Vladimir Vladimir Ashkenazy, Principal Conductor of Ashkenazy achieves what he does. Clark finds however, that the practice of making music in the the Sydney Symphony, talks with Robert Clark maestro’s realm is more spiritual than tangible. and ponders the mysteries of making music Just one month into the Wagner anniversary year 3 Simon Says and we appear to be pleasantly awash with all things 6 Brett Weymark Interview Wagnerian. In a one page special review, Randolph Magri-Overend lifts the lid on a commemorative 8 Un Ballo in Maschera – Solti Ring cycle 14 CD Box set limited edition and the Wagner Society in NSW unveils a Birth of an Opera packed calendar of events. 11 Presenter Profile – Tom Zelinka Over at the Sydney Symphony, Chief Conductor and Artistic Director designate David Robertson is set to mark the 200th anniversaries of Verdi and Wagner with two July 12 Young Virtuosi events - Verdi’s Requiem and a concert version of Wagner’s Flying Dutchman. 13 Meet Kathryn Selby These two concerts are among seven this year where the Sydney Symphony teams up with the Brett Weymark-led Sydney Philharmonia Choirs. -

The Life and Times of the Remarkable Alf Pollard

1 FROM FARMBOY TO SUPERSTAR: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REMARKABLE ALF POLLARD John S. Croucher B.A. (Hons) (Macq) MSc PhD (Minn) PhD (Macq) PhD (Hon) (DWU) FRSA FAustMS A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology, Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August 2014 2 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 12 August 2014 3 INTRODUCTION Alf Pollard’s contribution to the business history of Australia is as yet unwritten—both as a biography of the man himself, but also his singular, albeit often quiet, achievements. He helped to shape the business world in which he operated and, in parallel, made outstanding contributions to Australian society. Cultural deprivation theory tells us that people who are working class have themselves to blame for the failure of their children in education1 and Alf was certainly from a low socio-economic, indeed extremely poor, family. He fitted such a child to the letter, although he later turned out to be an outstanding counter-example despite having no ‘built-in’ advantage as he not been socialised in a dominant wealthy culture. -

Hamokara: a System for Practice of Backing Vocals for Karaoke

HAMOKARA: A SYSTEM FOR PRACTICE OF BACKING VOCALS FOR KARAOKE Mina Shiraishi, Kozue Ogasawara, and Tetsuro Kitahara College of Humanities and Sciences, Nihon University shiraishi,ogasawara,kitahara @kthrlab.jp { } ABSTRACT the two singers do not have sufficient singing skill, the pitch of the backing vocals may be influenced by the lead Creating harmony in karaoke by a lead vocalist and a back- vocals. To avoid this, the backing vocalist needs to learn to ing vocalist is enjoyable, but backing vocals are not easy sing accurately in pitch by practicing the backing vocals in for non-advanced karaoke users. First, it is difficult to find advance. musically appropriate submelodies (melodies for backing In this paper, we propose a system called HamoKara, vocals). Second, the backing vocalist has to practice back- which enables a user to practice backing vocals. This ing vocals in advance in order to play backing vocals accu- system has two functions. The first function is automatic rately, because singing submelodies is often influenced by submelody generation. For popular music songs, the sys- the singing of the main melody. In this paper, we propose tem generates submelodies and indicates them with both a backing vocals practice system called HamoKara. This a piano-roll display and a guide tone. The second func- system automatically generates a submelody with a rule- tion is support of backing vocals practice. While the user based or HMM-based method, and provides users with is singing the indicated submelody, the system shows the an environment for practicing backing vocals. Users can pitch (fundamental frequency, F0) of the singing voice on check whether their pitch is correct through audio and vi- the piano-roll display. -

OBITUARY: JOHN SANGSTER 1928-1995 by Bruce Johnson

OBITUARY: JOHN SANGSTER 1928-1995 by Bruce Johnson _________________________________________________________ ohn Grant Sangster, musician/composer, was born 17 November 1928 in Melbourne, only child of John Sangster and Isabella (née Davidson, then J Pringle by first marriage). He attended Sandringham (1933), then Vermont Primary Schools, and Box Hill High School. Self-taught on trombone then cornet, learning from recordings with friend Sid Bridle, with whom he formed a band. Sangster on cornet: self-taught first on trombone, then cornet… PHOTO COURTESY AUSTRALIAN JAZZ MUSEUM Isabella’s hostility towards John and his jazz activities came to a head on 21 September 1946, when she withdrew permission for him to attend a jazz event; in the ensuing confrontation he killed her with an axe but was acquitted of both murder and manslaughter. In December 1946 he attended the first Australian Jazz Convention (AC) in Melbourne, December 1946, and at the third in 1948 he won an award from Graeme Bell as ‘the most promising player’. He first recorded December 30th, and participated in the traditional jazz scene, including through the community centred on the house of Alan Watson in Rockley Road, South Yarra. 1 He married Shirley Drew 18 November 1949. In 1950 recorded (drums) with Roger, then Graeme Bell, and was invited to join Graeme’s band on drums for their second international tour (26 October 1950 to 15 April 1952). During this tour Sangster recorded his first composition, and encountered Kenny Graham’s Afro-Cubists and Johnny Dankworth, which broadened his stylistic interests. Graeme Bell invited Sangster to join Graeme’s band on drums for their second international tour, October 1950 to April 1952.. -

Festival of Perth Programmes (From 2000 Known As Perth International Arts Festival)

FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 2000 KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer Principals 1980 1980 Festival of Perth Festival Programme 14 Feb-18 Mar 1980 Various Festival at Bunbury WA Arts Council & City of Bunbury Feb – Mar 1980 Various PBS Festival of Perth Festival of Perth 1980 Spike Milligan, Tim Theatre Brooke-Taylor, Cathy Downes 17 Feb-16 Mar 1980 Churchill Gallery Lee Musgrave Paintings on Perspex 22 Feb-15 Mar 1980 Perth Concert Hall The Festival Club Bank of NSW Various 22 Feb 1980 Supreme Court Opening Concert Captain Colin Harper David Hawkes Compere Various Bands, Denis Gardens Walter Singer 23 Feb 1980 St George’s Cathedral A Celebration Festival of Perth 1980 The Very Reverend Cathedral Choir, David Robarts Address Cathedral Bellringers, Arensky Quartet, Anthony Howes 23 Feb 1980 Perth Concert Hall 20th Century Music Festival of Perth 1980, David Measham WA Symphony ABC Conductor Orchestra, Ashley Arbuckle Violin 23 Feb – 4 Mar 1980 Dolphin Theatre Richard Stilgoe Richard Stilgoe Take Me to Your Lieder 23 Feb-15 Mar 1980 Dolphin Theatre Northern Drift Alfred Bradley Henry Livings, Alan Glasgow 24 Feb 1980 Supreme Court Tops of the Pops for Festival of Perth 1980, Harry Bluck Various groups and Gardens ‘80 R & I Bank, SGIO artists 24 Feb, 2 Mar 1980 Art Gallery of WA The Arensky Piano Trio Festival of Perth 1980, Jack Harrison Clarinet playing Brahms Alcoa of Aust Ltd 25 Feb 1980 Perth Entertainment Ballroom Dance Festival of Perth 1980 Sam Gilkison Various dancing PR10960/1980-1989 -

Year of Publication: 2006 Citation: Lawrence, T

University of East London Institutional Repository: http://roar.uel.ac.uk This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Lawrence, Tim Article title: “I Want to See All My Friends At Once’’: Arthur Russell and the Queering of Gay Disco Year of publication: 2006 Citation: Lawrence, T. (2006) ‘“I Want to See All My Friends At Once’’: Arthur Russell and the Queering of Gay Disco’ Journal of Popular Music Studies, 18 (2) 144-166 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-1598.2006.00086.x DOI: 10.1111/j.1533-1598.2006.00086.x “I Want to See All My Friends At Once’’: Arthur Russell and the Queering of Gay Disco Tim Lawrence University of East London Disco, it is commonly understood, drummed its drums and twirled its twirls across an explicit gay-straight divide. In the beginning, the story goes, disco was gay: Gay dancers went to gay clubs, celebrated their newly liberated status by dancing with other men, and discovered a vicarious voice in the form of disco’s soul and gospel-oriented divas. Received wisdom has it that straights, having played no part in this embryonic moment, co-opted the culture after they cottoned onto its chic status and potential profitability. -

CGEN Program Guidelines

Program guidelines Be part of Queensland’s largest annual youth performing arts show at the Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre Show week: Tuesday 13 July to Saturday 17 July 2021 Principal partner Major partner Broadcast Event Program Program partner partner partner partner 200002 Contents Contact information............................................................................................. 1 What is Creative Generation – State Schools Onstage? .........................................2 Behaviour ...........................................................................................................2 COVID-19 information ..........................................................................................2 Nomination process ............................................................................................3 1. VOCAL ...........................................................................................................6 Featured and backing vocalist ........................................................................................7 Choir .............................................................................................................................8 2. DANCE and DRAMA .........................................................................................11 Featured and solo dance ............................................................................................... 11 Massed dance and regional massed dance ................................................................. -

Joseph Tawadros

RIVERSIDE THEATRES PRESENTS JOSEPH TAWADROS Riverside presents City of Holroyd Brass Band QUARTEand PackeminT Productions MUSIC SUNDAY 28 FEB AT 3PM boundaries; a migrant success story BIOGRAPHIES founded on breathtaking talent and a larrikin sense of humour. JOSEPH Joseph has toured extensively headlining in Europe, America, Asia and the Middle TAWADROS East and has collaborated with artists Oud such as tabla master Zakir Hussain, Despite being just 32, Joseph Tawadros has sarangi master Sultan Khan, Banjo already achieved great success. His three maestro Bela Fleck, John Abercrombie, recent albums, Permission to Evaporate, Jack DeJohnette, Christian McBride, Mike Chameleons of the White Shadows and Stern, Richard Bona, Ivry Gitlis, Neil Finn Concerto of the Greater Sea took out ARIAs and Katie Noonan. He has also had guest for Best World Music Album. Every single appearances with the Sydney, Adelaide and one of his albums has been nominated Perth Symphony Orchestras. for ARIA recognition. He blends and blurs Joseph is also recognised for his mastery musical tradition while crossing genres and of the instrument in the Arab world. He has the end result is magical. He has recorded, been invited to adjudicate the Damascus composed for and performed with many of International Oud Competition in 2009, to the biggest international jazz and classical perform at Istanbul’s inaugural Oud Festival artists. Joseph continues to create modern in 2010 and at the Institut du Monde Arabe, platforms for one of the world’s oldest Paris in 2013. instruments, remaining true to its soul while pairing it with unlikely accents. 2015 saw a national tour with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, as well Joseph is the recipient of an Order of as performances at Melbourne Recital Australia 2016, winner of the 2014 NSW Centre, Elder Hall (Adelaide) and the highly Premier’s Multicultural Award for Arts and anticipated release of his twelfth album, Culture, and finalist for Young Australian of Truth Seekers, Lovers and Warriors for ABC the Year in 2013. -

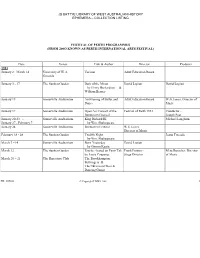

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A.