The Distribution of the Brazil Nut (Bertholletia Excelsa)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calophyllum Inophyllum L

Calophyllum inophyllum L. Guttiferae poon, beach calophyllum LOCAL NAMES Bengali (sultanachampa,punnang,kathchampa); Burmese (ph’ông,ponnyet); English (oil nut tree,beauty leaf,Borneo mahogany,dilo oil tree,alexandrian laurel); Filipino (bitaog,palo maria); Hindi (surpunka,pinnai,undi,surpan,sultanachampa,polanga); Javanese (njamplung); Malay (bentagor bunga,penaga pudek,pegana laut); Sanskrit (punnaga,nagachampa); Sinhala (domba); Swahili (mtondoo,mtomondo); Tamil (punnai,punnagam,pinnay); Thai (saraphee neen,naowakan,krathing); Trade name (poon,beach calophyllum); Vietnamese (c[aa]y m[uf]u) Calophyllum inophyllum leaves and fruit (Zhou Guangyi) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Calophyllum inophyllum is a medium-sized tree up to 25 m tall, sometimes as large as 35 m, with sticky latex either clear or opaque and white, cream or yellow; bole usually twisted or leaning, up to 150 cm in diameter, without buttresses. Outer bark often with characteristic diamond to boat- shaped fissures becoming confluent with age, smooth, often with a yellowish or ochre tint, inner bark usually thick, soft, firm, fibrous and laminated, pink to red, darkening to brownish on exposure. Crown evenly conical to narrowly hemispherical; twigs 4-angled and rounded, with plump terminal buds 4-9 mm long. Shade tree in park (Rafael T. Cadiz) Leaves elliptical, thick, smooth and polished, ovate, obovate or oblong (min. 5.5) 8-20 (max. 23) cm long, rounded to cuneate at base, rounded, retuse or subacute at apex with latex canals that are usually less prominent; stipules absent. Inflorescence axillary, racemose, usually unbranched but occasionally with 3-flowered branches, 5-15 (max. 30)-flowered. Flowers usually bisexual but sometimes functionally unisexual, sweetly scented, with perianth of 8 (max. -

The Miracle Resource Eco-Link

Since 1989 Eco-Link Linking Social, Economic, and Ecological Issues The Miracle Resource Volume 14, Number 1 In the children’s book “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein the main character is shown to beneÞ t in several ways from the generosity of one tree. The tree is a source of recreation, commodities, and solace. In this parable of giving, one is impressed by the wealth that a simple tree has to offer people: shade, food, lumber, comfort. And if we look beyond the wealth of a single tree to the benefits that we derive from entire forests one cannot help but be impressed by the bounty unmatched by any other natural resource in the world. That’s why trees are called the miracle resource. The forest is a factory where trees manufacture wood using energy from the sun, water and nutrients from the soil, and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In healthy growing forests, trees produce pure oxygen for us to breathe. Forests also provide clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities to renew our spirits. Forests, trees, and wood have always been essential to civilization. In ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq), the value of wood was equal to that of precious gems, stones, and metals. In Mycenaean Greece, wood was used to feed the great bronze furnaces that forged Greek culture. Rome’s monetary system was based on silver which required huge quantities of wood to convert ore into metal. For thousands of years, wood has been used for weapons and ships of war. Nations rose and fell based on their use and misuse of the forest resource. -

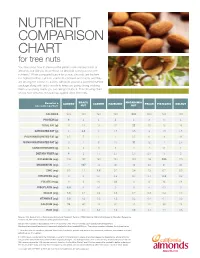

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Bioactive Compounds in Nuts and Edible Seeds: Focusing on Brazil Nuts and Baru Almond of the Amazon and Cerrado Brazilian Biomes

Review Article SM Journal of Bioactive Compounds in Nuts and Nutrition and Edible Seeds: Focusing on Brazil Nuts Metabolism and Baru Almond of the Amazon and Cerrado Brazilian Biomes Egea MB1*, Lima DS1, Lodete AR1 and Takeuchi K1,2* 1Science and Technology, Goiano Institute of Education, Brazil 2Faculty of Nutrition, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil Article Information Abstract Received date: Oct 09, 2017 The biodiversity of the Amazon and Cerrado biomes is extremely important for the populations that inhabit Accepted date: Nov 14, 2017 these areas, through the extractive collection of non-timber forest products such as fruits, nuts and edible seeds, which generate income and employment. Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is native from South America being Published date: Nov 20, 2017 found in the Amazon biome and baru almond (Dipteryx alata Vog.) is native from the Cerrado biome; these are part of the group of oleaginous that can be classified as true nuts and edible seeds, respectively. Both *Corresponding author are important sources of micronutrients that have been associated with several benefits to human health due to the presence of high levels of biologically active compounds such as minerals and vitamins. Minerals act Egea MB, Science and Technology, mostly as cofactors in various reactions, selenium has high availability in Brazil nuts and from selenocysteine Goiano Institute of Education, Brazil, and its enzymes, it exerts functions in the human body as an antioxidant, regulator of thyroid hormones and Tel: +55 64 36205636; protection of cardiovascular diseases. Among vitamins, tocopherol is a precursor to vitamin E, present in both Brazil nut and baru almond, being found in the form of α-tocopherol and having a role in the prevention of various Email: [email protected] diseases, including: cancer, diabetes, cataracts and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. -

Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Mi Bee Lab 9-21-1990 Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera) Charles D. Michener University of Kansas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Michener, Charles D., "Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)" (1990). Mi. Paper 153. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Bee Lab at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 WWvyvlrWryrXvW-WvWrW^^ I • • •_ ••^«_«).•>.• •.*.« THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS SCIENC5;^ULLETIN LIBRARY Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 75-164 Sept. 21,1990 OCT 23 1990 HARVARD Classification of the Apidae^ (Hymenoptera) BY Charles D. Michener'^ Appendix: Trigona genalis Friese, a Hitherto Unplaced New Guinea Species BY Charles D. Michener and Shoichi F. Sakagami'^ CONTENTS Abstract 76 Introduction 76 Terminology and Materials 77 Analysis of Relationships among Apid Subfamilies 79 Key to the Subfamilies of Apidae 84 Subfamily Meliponinae 84 Description, 84; Larva, 85; Nest, 85; Social Behavior, 85; Distribution, 85 Relationships among Meliponine Genera 85 History, 85; Analysis, 86; Biogeography, 96; Behavior, 97; Labial palpi, 99; Wing venation, 99; Male genitalia, 102; Poison glands, 103; Chromosome numbers, 103; Convergence, 104; Classificatory questions, 104 Fossil Meliponinae 105 Meliponorytes, -

UNECE Standard for Pine Nuts (DDP-12)

UNECE STANDARD DDP-12 concerning the marketing and commercial quality control of PINE NUT KERNELS 2013 EDITION UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2013 NOTE Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards The commercial quality standards developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards help facilitate international trade, encourage high-quality production, improve profitability and protect consumer interests. UNECE standards are used by Governments, producers, traders, importers and exporters, and other international organizations. They cover a wide range of agricultural products, including fresh fruit and vegetables, dry and dried produce, seed potatoes, meat, cut flowers, eggs and egg products. Any member of the United Nations can participate, on an equal footing, in the activities of the Working Party. For more information on agricultural standards, please visit our website http://www.unece.org/trade/agr/welcome.html. The new Standard for Pine Nut Kernels is based on document ECE/TRADE/C/WP.7/2013/31, reviewed and adopted by the Working Party at its sixty-ninth session. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of company -

Fats Ebook Feb 02.Pdf

2 DRHYMAN.COM Contents Contents INTRODUCTION ................................. 8 PART I ........................................... 11 Dietary Fats: The Good, Bad and the Ugly ............................................ 11 Fatty Acids ............................................................................................ 11 Saturated Fat ........................................................................................ 12 Polyunsaturated Fats ............................................................................ 14 Essential Fatty Acids 101- Omega-3 and Omega-6 ............................... 14 The Beneficial Omega-6 Fatty Acid: GLA ............................................... 16 How Fatty Acids Affect Brain Health ..................................................... 17 Omega-7 Fatty Acids ............................................................................ 18 Monounsaturated Fat ............................................................................ 18 Trans Fats ............................................................................................. 20 Trans Fats and Health ........................................................................... 21 Toxins in Fat .......................................................................................... 22 A Case for Organic ................................................................................ 23 DRHYMAN.COM 3 PART II .......................................... 24 Animal Fats ....................................................................... -

Various Terminologies Associated with Areca Nut and Tobacco Chewing: a Review

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Vol. 19 Issue 1 Jan ‑ Apr 2015 69 REVIEW ARTICLE Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review Kalpana A Patidar, Rajkumar Parwani, Sangeeta P Wanjari, Atul P Patidar Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Modern Dental College and Research Center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Kalpana A Patidar, Globally, arecanut and tobacco are among the most common addictions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Tobacco and arecanut alone or in combination are practiced in different regions Modern Dental College and Research Centre, in various forms. Subsequently, oral mucosal lesions also show marked Airport Road, Gandhi Nagar, Indore ‑ 452 001, Madhya Pradesh, India. variations in their clinical as well as histopathological appearance. However, it E‑mail: [email protected] has been found that there is no uniformity and awareness while reporting these habits. Various terminologies used by investigators like ‘betel chewing’,‘betel Received: 26‑02‑2014 quid chewing’,‘betel nut chewing’,‘betel nut habit’,‘tobacco chewing’and ‘paan Accepted: 28‑03‑2015 chewing’ clearly indicate that there is lack of knowledge and lots of confusion about the exact terminology and content of the habit. If the health promotion initiatives are to be considered, a thorough knowledge of composition and way of practicing the habit is essential. In this article we reviewed composition and various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco habits in an effort to clearly delineate various habits. Key words: Areca nut, habit, paan, quid, tobacco INTRODUCTION Tobacco plant, probably cultivated by man about 1,000 years back have now crept into each and every part of world. -

Virtually Bringing the Nut & Dried Fruit Sector Together

Edition 81. Nº 3 November 2020 INC ONLINE CONFERENCE Virtually Bringing the Nut & Dried Fruit Sector Together p. 57 www.nutfruit.org November 2020 | NUTFRUIT November 2020 | NUTFRUIT Edition 81. Nº 3 November 2020 The INC is the international umbrella organization for the nut and dried fruit industry and the source for information on health, nutrition, statistics, food safety, and international standards and regulations regarding nuts and dried fruits. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Michael Waring - Chairman Business News 9 INC Congress 54 MWT Foods, Australia Ashok Krishen - 1st Vice Chairman 9 Partnership Besana-Importaco 54 Dubai, INC XXXIX World Nut and Dried Olam International Limited, Singapore Fruit Congress Pino Calcagni - 2nd Vice Chairman 10 PepsiCo Targets 100% Renewable Besana Group, Italy Electricity Globally Riccardo Calcagni Besana Group, Italy 11 Danone’s Alpro Celebrates 40 Years INC News 57 Bill Carriere Carriere Family Farms, USA 12 Creamy, Crunchy, Chewy: Introducing 57 INC Online Conference Karsten Dankert Nature Valley Packed, a New Sustained Max Kiene GmbH, Germany Energy Bar 60 INC Academia: The Best Training Program in Roby Danon the Nut and Dried Fruit Industry Voicevale Ltd, UK Cao Derong 62 INC Webinars China Chamber of Commerce, China Gourmet 14 Joan Fortuny Borges Agricultural & Industrial Nuts (BAIN), Spain 63 Trend Research: International Market Giles Hacking 14 Carme Ruscalleda, Barcelona, Spain Opportunities CG Hacking & Sons Limited, UK Mike Hohmann 64 Real Power for Real People: Boost your The Wonderful Company, -

Pollination Requirements and the Foraging Behavior of Potential Pollinators of Cultivated Brazil Nut (Bertholletia Excelsa Bonpl.) Trees in Central Amazon Rainforest

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Psyche Volume 2012, Article ID 978019, 9 pages doi:10.1155/2012/978019 Research Article Pollination Requirements and the Foraging Behavior of Potential Pollinators of Cultivated Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) Trees in Central Amazon Rainforest M. C. Cavalcante,1 F. F. Oliveira, 2 M. M. Maues,´ 3 and B. M. Freitas1 1 Department of Animal Science, Federal University of Ceara´ (UFC), Avenida Mister Hull 2977, Campus do Pici, CEP 60021-970, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil 2 Department of Zoology, Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Rua Barao˜ de Geremoabo 147, Campus de Ondina, CEP 40170-290, Salvador, BA, Brazil 3 Entomology Laboratory, Embrapa Amazoniaˆ Oriental (CPATU), Travavessa Dr. En´eas Pinheiro s/n, CEP 66095-100, Bel´em, PA, Brazil Correspondence should be addressed to B. M. Freitas, [email protected] Received 5 December 2011; Revised 7 March 2012; Accepted 25 March 2012 Academic Editor: Tugrul Giray Copyright © 2012 M. C. Cavalcante et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This study was carried out with cultivated Brazil nut trees (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl., Lecythidaceae) in the Central Amazon rainforest, Brazil, aiming to learn about its pollination requirements, to know the floral visitors of Brazil nut flowers, to investigate their foraging behavior and to determine the main floral visitors of this plant species in commercial plantations. Results showed that B. excelsa is predominantly allogamous, but capable of setting fruits by geitonogamy. Nineteen bee species, belonging to two families, visited and collected nectar and/or pollen throughout the day, although the number of bees decreases steeply after 1000 HR. -

YSF 2020-PROGRAMME-1.Pdf

YOUNG SYSTEMATISTS' FORUM Day 1 Monday 23rd November 2020, Zoom [all timings are GMT+0] 11.50 Opening remarks David Williams, President of the Systematics Association 12.00 Rodrigo Vargas Pêgas Species Concepts and the Anagenetic Process Importance on Evolutionary History 12.15 Katherine Odanaka Insights into the phylogeny and biogeography of the cleptoparasitic bee genus Nomada 12.30 Minette Havenga Association among global populations of the Eucalyptus foliar pathogen Teratosphaeria destructans 12.45 David A. Velasquez-Trujillo Phylogenetic relationships of the whiptail lizards of the genus Holcosus COPE 1862 (Squamata: Teiidae) based on morphological and molecular evidence 13.00 Break 10 minutes 13.10 Arsham Nejad Kourki The Ediacaran Dickinsonia is a stem-eumetazoan 13.25 Flávia F.Petean The role of the American continent on the diversification of the stingrays’ genus Hypanus Rafinesque, 1818 (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae) 13.40 Peter M.Schächinger Discovering species diversity in Antarctic marine slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 13.55 Alison Irwin Eight new mitogenomes clarify the phylogenetic relationships of Stromboidea within the gastropod phylogenetic framework 14.10 Break 20 minutes 14.30 Érica Martinha Silva de The lineages of foliage-roosting fruit bat Uroderma spp. (Chiroptera: Souza Phyllostomidae 14.45 Melissa Betters Rethinking Informative Traits: Environmental Influence on Shell Morphology in Deep-Sea Gastropods 15.00 J. Renato Morales-Mérida- New lineages of Holcosus undulatus (Squamata: Teiidae) in Guatemala 15.15 Roberto -

Sources and Frequency of Brood Loss in Solitary Bees

Apidologie Original Article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France SAS, part of Springer Nature, 2019 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-019-00663-2 Sources and frequency of brood loss in solitary bees 1 2 Robert L. MINCKLEY , Bryan N. DANFORTH 1Department of Biology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14620, USA 2Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Received4February2019– Revised 17 April 2019 – Accepted 4 June 2019 Abstract – We surveyed the literature for reports of parasites, predators, and other associates of the brood found in the nests of solitary bees. Studies were included in this survey if they reported the contents of all the bee brood cells that they examined. The natural enemies of solitary bees represented in the studies included here were taxonomically diverse. Although a few studies report high loss of solitary bee brood to a species-rich set of natural enemies, most studies report losses of less than 20% to few natural enemies. Brood parasitic bees are the greatest source of mortality for immatures of pollen-collecting solitary bees followed by meloid beetles (Meloidae), beeflies (Bombyliidae), and clerid beetles (Cleridae). Most groups, however, are reported from only a few host species and attack a low proportion of brood cells. Mortality due to unknown causes is also common. The suite of natural enemies that attack ground- and cavity-nesting solitary bees is very different. The cavity-nesting species have higher reported mortality due to unknown causes perhaps related to how nests are manipulated and handled by researchers. brood parasite / predator / cavity-nesting bees / ground-nesting bees / meta-analysis 1.