Stanford's Environmental Engineering and Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 24, 2008 (Download PDF)

Volume 53, Number 3 TechTalk Wednesday, September 24, 2008 S ERVING THE MIT CO mm UNI T Y 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 of the Mass. Ave. Bridge RULERLength : 2,164.8 feet (or 364.4 Smoots ± an ear) SMOOT ANNIVERSARY EVENTS: Oct. 4 Smoot reflects on his measurement Charles River clean up 11:30 a.m.-4 p.m. feat as 50th anniversary nears Volunteers from the MIT community and beyond gather at the Kresge Oval for a barbecue lunch before cleaning the shoreline of the Patrick Gillooly Charles River. MIT President Susan Hockfield, Oliver Smoot and other News Office guests will speak at 12:30 p.m. Visit web.mit.edu/smoot/schedule.htm to s his fraternity brothers laid his 5-foot, 7-inch frame end- register. to-end to measure the Massachusetts Avenue bridge one Herb Reed and the Platters Concert 5-6:30 p.m. Anight in October 1958, there was one distinct thought running through Oliver Smoot’s mind. Famed ’50s music group Herb Reed and the Platters play the MIT “It was pretty cold,” he said. Kresge Auditorium at 5 p.m. Pre-show tickets available for $25 online at Smoot ’62 evoked memories recently about the night his web.mit.edu/smoot/platters.htm; tickets at the door (if available) $35. name became a unit of measurement as MIT prepares to cele- brate the 50th anniversary of the quirky MIT Big ’50s Party 6:30-11 p.m. hack. A series of events has been planned The MIT Club of Boston, the Class of 1962 and Lambda Chi See web.mit.edu/ for the weekend of Oct. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

ARTHUR CLAY COPE June 27, 1909-June 4, 1966 by JOHN D

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES A RTHUR CLAY C OPE 1909—1966 A Biographical Memoir by J O H N D . RO BERTS AND JOHN C . S HEEHAN Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1991 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. ARTHUR CLAY COPE June 27, 1909-June 4, 1966 BY JOHN D. ROBERTS AND JOHN C. SHEEHAN RTHUR CLAY COPE, an extraordinarily influential and Aimaginative organic chemist, was born on June 27, 1909, and died on June 4, 1966. He was the son of Everett Claire Cope and Jennie (Compton) Cope, who lived in Dunreith, Indiana, but later moved to Indianapolis to enhance their son's educational possibilities. Everett Cope was in the grain storage business and his wife worked for some time at the local YWCA office. In 1929 Arthur received the bachelor's degree in chem- istry from Butler University in Indianapolis, then, with the support of a teaching assistantship, moved to the University of Wisconsin for graduate work. His thesis advisor at Wisconsin was S. M. McElvain, whose research program included the synthesis of organic com- pounds with possible pharmaceutical uses—especially local anesthetics and barbiturates. Cope's thesis work, completed in 1932, was along these lines. It led to the discovery of a useful local anesthetic and provided the major theme of his research for many years. Cope clearly made a strong impression at Wisconsin dur- ing his graduate career. He completed his thesis work and three independent publications in three years and was rec- ommended by the Wisconsin organic chemistry faculty (then 17 18 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS headed by the redoubtable Homer Adkins) for one of the highly sought-after National Research Council Fellowships at Harvard. -

A B C D E F G H I J K L M 0 P

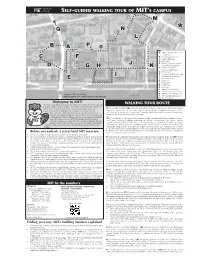

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF M.....IT’S CAMPUS ... M j .... Q N ....... * L ........ ........... B .....A P.. 0 ... .... Lobby 7 & Visitor Info Center ....... A ..... (77 Mass Ave) C F B Stratton Student Center C Kresge Auditorium .... MIT Chapel D E Building 1 (nearby entrance J to Hart Nautical Gallery) D........ ......... G ..... H K F Building 3/Design & ..... .... Manufacturing display ......... .............................. G Killian Court H Ellen Swallow Richards Lobby I I Hayden Memorial Library E J McDermott Court K Media Lab L North Court ......... M Koch Institute N Stata Center O Edgerton’s Strobe Alley P Memorial Lobby / Barker Library Q 1 smoot = 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Q MIT Museum (265 Mass Ave) Bridge length = 364.4 smoots, plus or minus one ear MIT Coop/Kendall Square Q* Smoot markings Welcome to MIT! forma- We hope you enjoy your visit! The tour route outlined on this map will WALKING TOUR ROUTEn help you explore MIT’s campus. The Office of Admissions conducts information sessions followed by student-led campus tours for u Leave Lobby 7 (Bldg. 7 [A]) and cross Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave). Central and Harvard prospective students and families, Mon–Fri, excluding federal, Squares are up the street to your right, and the Harvard Bridge (leading into Boston) is to your Massachusetts, and Institute holidays and the winter break left. Mass Ave is a main street connecting Cambridge and Boston, and bus stops servicing major period. Info sessions begin at 10 am and 2 pm; campus tours routes can be found on either side of the street. -

MIT Opencourseware

MIT OpenCourseWare MIT OpenCourseWare (OCW) is a free and open digital publication of high-quality educational materials organized as courses. Through the Internet, MIT OpenCourseWare has opened MIT’s curriculum and the course materials created by MIT faculty to a global audience of teachers and learners. In the United States and around the world educators use these materials for teaching and curriculum development, while students and self- learners draw upon the materials for self-study or supplementary use. Since the inception of OCW in 2001, more than 8,850 individuals, including nearly 70% of current MIT tenured or tenure-track faculty members, have voluntarily shared their teaching materials through OCW, amassing a collection of many thousands of individual resources, including documents, video, audio, simulations, animations, and sample programming code. An estimated 150 million individuals have accessed these resources, and hundreds of universities around the world have joined MIT in sharing their own course materials freely and openly on the web. Highlights of the Year Publication Status As of June 30, 2013, there were 2,168 courses available on OCW, representing virtually the entire undergraduate and graduate curricula in MIT’s five schools and 33 academic units. Among the live courses on OCW, 742 represent more recent versions of courses that were previously published on OCW. These updated courses have fresh materials, often including new pedagogical approaches. We publish about 40–50 new courses and 60–70 updated courses each year. An update normally requires the complete reassembly of the course site and therefore involves an effort equal to that needed for publishing a new course. -

Department of Chemistry

Department of Chemistry Chemistry is the science of creation, discovery, and understanding at the molecular level. Its achievements continue to fuel advances in other branches of science, in medicine, and in engineering. Major new initiatives in the department include the synthesis of novel molecules to turn sunlight into chemical energy, nitrogen into ammonia, and carbon dioxide into useful reagents, the invention of new tools to investigate complex biological processes including neurochemical signaling, methods to characterize the dynamics of water and the unfolding of proteins in solution, and the design and synthesis of electronic polymers. In academic year 2004, the Chemistry Department continued its strong programs in undergraduate and graduate education. Associated with the department currently are 260 graduate students, 98 postdoctoral researchers, and 104 undergraduate chemistry majors. As of July 1, 2004, the Chemistry Department faculty comprised 31 full‐time faculty members, including 6 assistant professors, 4 associate professors, and 21 full professors, including 1 Institute Professor. Effective July 1, 2003, Professors Jianshu Cao and Andrei Tokmakoff were promoted to associate professor without tenure. In the fall, professors Catherine L. Drennan and Timothy F. Jamison were promoted to associate professor without tenure, to take effect on July 1, 2004. Major Faculty Awards and Honors • Professor Moungi Bawendi was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. • Professor Sylvia T. Ceyer was elected fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science. • Professor Catherine L. Drennan received the Presidential Early Career Award, the Dean’s Educational and Student Advising Award, and the 2004 Edgerton Faculty Award. • Professor Gregory C. Fu received the 2004 E. -

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Justin S. Miller

CURRICULUM VITAE DR. JUSTIN S. MILLER Associate Professor 3324 Dandelion Trail Department of Chemistry Canandaigua, NY 14424 Hobart and William Smith Colleges Phone: (315) 781-3884 Geneva, NY 14456 Email: [email protected] Web: http://campus.hws.edu/academic/popup.asp?id=366 EDUCATION Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research Postdoctoral Fellow (2001 – 2004), Advisor: Dr. Samuel J. Danishefsky Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ph.D., Organic Chemistry (2001), Advisors: Dr. Daniel S. Kemp, Dr. Scott C. Virgil • Dissertation: “I. Efforts towards the Synthesis of CP-263,114. II. On Solubilized, Spaced Polyalanines and Amino Acid -Helix Propensities.” • Graduate Student Teaching Award (1998) Princeton University A.B., Chemistry (1995), Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz • Senior thesis: “The Reduction of Methyl Cinnamate by Titanocene Borohydride: A Mechanistic Study.” ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, organic chemistry, Hobart and William Smith Colleges (HWS) (2010 – present; Chair 2013 – present) Assistant Professor, organic chemistry, Hobart and William Smith Colleges (HWS) (2004 – 2010) Research interests • Peptide and protein synthetic methodology • Organic synthesis of bioactive molecules • Principles of bioorganic chemistry Courses taught • Introductory and intermediate organic chemistry, including laboratory • Bonding with Food: The Chemistry of Food Preparation, Production, and Policy • Advanced organic chemistry • Introductory general chemistry, including laboratory EXTERNAL GRANT FUNDING co-PI, NSF – Transforming Undergraduate -

Interview with John D. Roberts

JOHN D. ROBERTS (1918-2016) INTERVIEWED BY RACHEL PRUD’HOMME February-May, 1985 Photograph by Chris Tschoegl. Courtesy Caltech’s Engineering & Science ARCHIVES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California Subject area Chemistry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy Abstract Interview in seven sessions, February–May 1985, with John D. Roberts, Institute Professor of Chemistry (now emeritus) in the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. Family background, early education, Los Angeles; Caltech open houses in early 1930s. Studies chemistry, UCLA (BA 1941). Graduate work Penn State University with F. Whitmore; return to UCLA, war-related research; theoretical organic chemistry with S. Winstein (PhD 1944). 1945, NRC Fellowship, Harvard; R. B. Woodward. Assistant professorship MIT; recollections of A. Cope, A. A. Morton; L. Pauling’s theory of molecular resonance; molecular orbital theory of R. S. Mulliken. Research on carbonium ions, carbon cations with R. Mazur; dispute with S. Winstein. Consultant at DuPont, starting 1950. Guggenheim, Caltech, 1952; joins chemistry faculty 1953. H. Lucas, L. Pauling, other colleagues. Guggenheim to England. J. H. Sturdivant, V. Schomaker, D. Semenow, G. Whitesides. Election (1956) to NAS; heads http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechOH:OH_Roberts_J chemistry section; NAS response to W. Shockley and R. Lewontin affairs. NSF chemistry advisory panel (1957-1962); Mohole Seismological Drilling Project; faculty salaries. Writes Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1959), Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry (1964); W. A. Benjamin; collaboration with M. B. Caserio on Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry; writes Modern Organic Chemistry. NMR at Caltech; construction of NMR spectrometer lab; carbon-13 experiments; work of F. Wiegert, K. Kanamori; E. Swift, division chairman; H. -

Laboratory Manual 5.301 Chemistry Laboratory Techniques

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Chemistry CHE S RY © 1986 Ybet Laboratory Manual 5.301 Chemistry Laboratory Techniques Prepared by Katherine J. Franz and Kevin M. Shea with the assistance of Professors Rick L. Danheiser and Timothy M. Swager Revised by J. Haseltine, Kevin M. Shea, Sarah A. Tabacco, Kimberly L. Berkowski, Anne M. Rachupka and John J. Dolhun IAP 2013 5.301: Chemistry Laboratory Techniques IAP January 2013 Faculty & Staff Duties John J. Dolhun, Ph.D. Instructor for Course 5.301 Dr. Mariusz Twardowski Director of Undergraduate Labs Jennifer Weisman Academic Administrator Mary A. Turner Administrative Assistant Lynn Marie Guthrie Administrative Assistant Randall A. Scanga Technical Associate 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS See the attached Table of Contents on pages 1-2 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Experiment Techniques Covered: 1. Transfer and Extraction Techniques 2. Purification of Solids by Recrystallization 3. Purification of Liquids by Distillation 4. Protein Assays and Error Analysis 5. Introduction to Original Research Major Equipment Students will be Trained on: 1. Automated 5890 Series II Gas Chromatograph 2. Automated Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV-VIS Spectrometers 3. Varian Saturn 2000 Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer 4. Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 Series FT-IR 5. Varian Mercury 300MHz NMR Spectrometer 6. Rotary Evaporators 7. Auto Abbe Automatic Refractometer 2 5.301 Chemistry Laboratory Techniques IAP 2013 Instructor: John J. Dolhun TA’s: TBA January 8, 2013 thru January 28, 2013 Lecture: MTWRF 10-11 AM Laboratory: MTWRF 12-6:00 PM Course Highlights 5.301 includes a series of chemistry laboratory instructional videos called the Digital Lab Techniques Manual (DLTM), used as supplementary material for this course as well as other courses offered by the Chemistry department. -

5.310 Essential Oils

EXPERIMENT # 3: Essential Oils (EO) MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Department of Chemistry 5.310 Laboratory Chemistry EXPERIMENT #3 ESSENTIAL OILS1 I. INTRODUCTION In this experiment2 you will be working with oils prepared from caraway seeds and spearmint leaves. Each oil has a distinct and characteristic odor, yet carvone is the major component in both oils! It is amazing that the difference in odor is attributable solely to a difference in chirality of the carvone in the two oils. Due to chirality of odor receptors in the nose the R-carvone and S-carvone fit into different receptor sites, hence different odor. Can you distinguish between the odors? 8-10% of the population cannot.3 Some physical data4 are presented below. O O ∗ ∗ H H (S) -(+)-Carvone (R) -(-)-Carvone FW = 150.22; bp 98-100/10 mm Fw=150.22; bp 227-230 oC 20 20 nD = 1.4970; d=0.9608 g/mL nD = 1.4990; d=0.9593 g/mL 20 o 20 o [α]D =+61.7 (neat 96%) [α]D =-62.5 (neat 98%) major component of caraway oil major component of spearmint oil (Carum carvi) (Mentha spicata) 1The experiment includes contributions from past instructors, course textbooks, and others affiliated with course 5.310 updated by John Dolhun May 2017. 2 Adapted from: Pavia, D. L.; Lampman, G. M.; Kriz, G. S.; Engel, R. G. “Introduction to Organic Laboratory Techniques”; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, 1990, pp. 96-107. 3 ibid. p.103. 4 Physical data is taken from Aldrich Chemical Catalog 1998-1999 EO-1 EXPERIMENT # 3: Essential Oils (EO) All the physical properties should be identical except for the optical rotations of the two isomers (enantiomers), which are of opposite sign. -

ASMS Directory of Members

ASMS Directory of Members DAVID AASERUD FRED P ABRAMSON JEANETTE ADAMS DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY DEPARTMENT OF PHARMACOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY BOX 342, BAKER LAB GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY EMORY UNIVERSITY CORNELL UNIVERSITY 2300 EYE STREET NORTHWEST ATLANTA, GA30322 ITHACA, NY 14853 WASHINGTON , DC 20037 Phone: 404 7276522 Phone: 6072553731 Phone: 2029942946 Fax: 404 7276586 Fax: 607255-7880 Fax: 202 994 2870 [email protected] LARRY ABBEY ANDREW ACHEAMPONG NATHAN ADAMS TRIANGLE LABS OF ATLANTA, INC ALLERGAN PHARMACEUTICALS DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY \703 WEBB DR, SUITE C 2525 DUPONT DRIVE UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN lOWA NORCROSS , GA 30093 IRVINE, CA 92715 CEDAR FALLS, IA 50614-0423 Phone: 4044466393 Phone: 714 724 4950 Phone: 3192732435 Fax: 4044466392 Fax: 714 724 5850 [email protected] FRANK S ABBOTT BRADLEY L ACKERMANN NIGEL G ADAMS FACULTY OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCI MARION MERRELL DOW, INC DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 2110 E GALBRAITH ROAD UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA 2\46 EAST MALL BLDG. 26-1 ATHENS, GA 30602 VANCOUVER, BC, V6T \23 CINCINNATI, OH 45215-6300 Phone : 4045423722 CANADA Phone: 513 948 6081 Fax: 4045429454 Phone: 604822 2566 Fax: 513 9487360 [email protected] Fax: 6048223035 [email protected]!vID.COM ROBERT A ADAMS MAGED ABDELRAHIM MICHAELRACKERMANN ARLSINC. WALTER REED ARMY MEDICAL CTR FISONS INSTRUMENTS 3480 TANBARK CT. NE DEPT OF CLINICAL INVESTIGATION 55 CHERRY HILL DRIVE ATLANTA, GA30319 WASHINGTON, DC 20307 BEVERLY, MA 01915 Phone: 4042554817 Phone: 202 782 7612 Phone: 508524 -

2008 Umsl Chemist

UUMMSSLL CCHHEEMMIISSTT Volume 26 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry Fall 2008 Lawrence Barton, Editor TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman's Message (Christopher D. Spilling) …….………1 Alumni Information ……………………………………….2 Ted Windsor…………………………………………………..12 Events, graduates, chemistry club……………………………12 Faculty, and staff ………………………………………… 13 Student Fellowships and Awards ……………...............18 Editor's Column (Lawrence Barton) ……………………….20 Contributors 2008 ..…………………………………………21 Information update ....……...………………………………. 23 Chairman's Message (Christopher D. Spilling) I am writing this year’s message in a condo in Winter Park, Colorado. My family and I were lucky enough to take a skiing vacation over the Thanksgiving break, but like many of you, work is always with me in the form of a laptop and the internet. Dr. Spilling and Chancellor Tom George Last year I reported that we were busy searching for We had also had large turnover in the technical staff over the replacements for Lol Barton and Joyce Corey. This year I am last couple of years. However, we are now at full strength with the addition of Bruce Burkeen as the departmental machinist, John Tubbesing as electronics technician and Joe Flunker as scientific glassblower. The Department and the University, like many of you, have felt the problems with economy and we were lucky to complete all of hiring before the University wide hiring freeze was established. However, the machine shops of chemistry and physics were combined recently due to the retirement of physics machinist, Jim Sliefert. Planning for the new undergraduate science lab building and the renovation of Benton Hall is proceeding well. A new three story building will be built perpendicular to Benton Hall towards Natural Bridge Road and will house the undergraduate teaching labs for Chemistry, Physics and Biology.