ARTHUR CLAY COPE June 27, 1909-June 4, 1966 by JOHN D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies of a Dirhodium Tetraphosphine Catalyst for Hydroformylation And

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Studies of a dirhodium tetraphosphine catalyst for hydroformylation and aldehyde-water shift ac talysis Aaron Rider Barnum Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Barnum, Aaron Rider, "Studies of a dirhodium tetraphosphine catalyst for hydroformylation and aldehyde-water shift catalysis" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3998. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3998 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. STUDIES OF A DIRHODIUM TETRAPHOSPHINE CATALYST FOR HYDROFORMYLATION AND ALDEHYDE-WATER SHIFT CATALYSIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Chemistry by Aaron Rider Barnum B.S. Loyola University New Orleans, 2007 December 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my family, for without their encouragements and support I would not be where I am today. To my parents, Otis and Cindy Barnum, thank you for everything throughout the years. To my grandmother Teruko, you are responsible for two things I hold very dear to my heart: inspiring me to become the scientist and chemist I am today and also for keeping me in touch with my Japanese heritage. -

September 24, 2008 (Download PDF)

Volume 53, Number 3 TechTalk Wednesday, September 24, 2008 S ERVING THE MIT CO mm UNI T Y 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 of the Mass. Ave. Bridge RULERLength : 2,164.8 feet (or 364.4 Smoots ± an ear) SMOOT ANNIVERSARY EVENTS: Oct. 4 Smoot reflects on his measurement Charles River clean up 11:30 a.m.-4 p.m. feat as 50th anniversary nears Volunteers from the MIT community and beyond gather at the Kresge Oval for a barbecue lunch before cleaning the shoreline of the Patrick Gillooly Charles River. MIT President Susan Hockfield, Oliver Smoot and other News Office guests will speak at 12:30 p.m. Visit web.mit.edu/smoot/schedule.htm to s his fraternity brothers laid his 5-foot, 7-inch frame end- register. to-end to measure the Massachusetts Avenue bridge one Herb Reed and the Platters Concert 5-6:30 p.m. Anight in October 1958, there was one distinct thought running through Oliver Smoot’s mind. Famed ’50s music group Herb Reed and the Platters play the MIT “It was pretty cold,” he said. Kresge Auditorium at 5 p.m. Pre-show tickets available for $25 online at Smoot ’62 evoked memories recently about the night his web.mit.edu/smoot/platters.htm; tickets at the door (if available) $35. name became a unit of measurement as MIT prepares to cele- brate the 50th anniversary of the quirky MIT Big ’50s Party 6:30-11 p.m. hack. A series of events has been planned The MIT Club of Boston, the Class of 1962 and Lambda Chi See web.mit.edu/ for the weekend of Oct. -

Vinyl Ether Functional Polyurethanes As Novel Photopolymers

Vinyl Ether Functional Polyurethanes as Novel Photopolymers Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades „Doktor der Naturwissenschaften” im Promotionsfach Chemie am Fachbereich Chemie, Pharmazie und Geowissenschaften der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Stefan Kirschbaum geboren in Köln Mainz, 2015 Dekan: 1. Berichterstatter: 2. Berichterstatter: Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. Dezember 2015 Ich versichere, die als Dissertation vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig angefertigt zu haben und alle verwendeten Quellen und Hilfsmittel kenntlich gemacht zu haben. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von Oktober 2012 bis November 2015 unter Betreuung von in Kooperation zwischen dem Max-Planck-Institut für Polymerforschung in Mainz und der Henkel AG und Co. KGaA in Düsseldorf angefertigt. IV Introduction Table of Content 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Theoretical Background ...................................................................................... 5 2.1 Basic Considerations of Photocuring ........................................................................ 5 2.1.1 Photoinitiation and Electronic States ............................................................................ 6 2.1.2 Cationic Photoinitiators .............................................................................................. 11 2.1.3 Photoinduced Cationic Polymerization ...................................................................... 14 2.1.4 Photoinduced Radical Polymerization -

United States Patent Office Patented Mar

2,738,364 United States Patent Office Patented Mar. 13, 1956 2 examples of the type of catalyst, we refer to N-butyl - 2,738,364 pyridinium nickel bromide of the formula PRODUCTION OF ACRYLIC ACID ESTERs IC5H5N.C4H9)2(NiBral Walter Reppe and Walter Schweckendiek, Ludwigshafen (Rhine), and Herbert Friederich, Worms, Germany, as 5 or dimethyl phenyl ethyl ammonium nickel chloride of signors to Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik Aktiengesel the formula (CH3)2. (CoHs). (C2H5)Ni2. (NiCl4). We schaft, Ludwigshafen am Rhine, Germany may also use salts containing in the molecule a tertiary amine in addition to an ammonium radical, e. g. a com No Drawing. Application May 17, 1952, pound of the composition Serial No. 288,534 O Claims priority, application Germany June 5, 1951 (C5H5N.C4H9). (C5H5N1.INiBral In the compounds listed above the pyridine radical 16 Claims. (Cl. 260-486) may be replaced by other heterocyclic nitrogen compounds or by other tertiary amines of the types referred to The present invention relates to the production of 5 above. The chlorine and bromine radicals may be re acrylic acid esters and, more particularly, to the synthesis placed by iodine or cyanide or rhodanide. of acrylic esters by the interaction of acetylene, carbon The novel catalysts may be used in combination with ofmonoxide carbonylation and alcohols catalysts. in the presence of a novel type complex tertiary phosphine nickel salts, e.g. with triphenyl It is known that acrylic acid and its functional deriva 20 phosphine nickel bromide (C6H5)3P)2.NiBr2 or with tives may be prepared by the interaction of acetylen and quaternary phosphonium compounds derived therefrom, carbon monoxide with compounds having a replaceable e.g. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

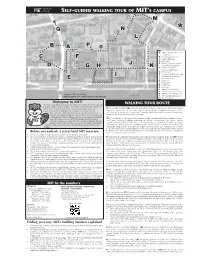

A B C D E F G H I J K L M 0 P

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF M.....IT’S CAMPUS ... M j .... Q N ....... * L ........ ........... B .....A P.. 0 ... .... Lobby 7 & Visitor Info Center ....... A ..... (77 Mass Ave) C F B Stratton Student Center C Kresge Auditorium .... MIT Chapel D E Building 1 (nearby entrance J to Hart Nautical Gallery) D........ ......... G ..... H K F Building 3/Design & ..... .... Manufacturing display ......... .............................. G Killian Court H Ellen Swallow Richards Lobby I I Hayden Memorial Library E J McDermott Court K Media Lab L North Court ......... M Koch Institute N Stata Center O Edgerton’s Strobe Alley P Memorial Lobby / Barker Library Q 1 smoot = 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Q MIT Museum (265 Mass Ave) Bridge length = 364.4 smoots, plus or minus one ear MIT Coop/Kendall Square Q* Smoot markings Welcome to MIT! forma- We hope you enjoy your visit! The tour route outlined on this map will WALKING TOUR ROUTEn help you explore MIT’s campus. The Office of Admissions conducts information sessions followed by student-led campus tours for u Leave Lobby 7 (Bldg. 7 [A]) and cross Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave). Central and Harvard prospective students and families, Mon–Fri, excluding federal, Squares are up the street to your right, and the Harvard Bridge (leading into Boston) is to your Massachusetts, and Institute holidays and the winter break left. Mass Ave is a main street connecting Cambridge and Boston, and bus stops servicing major period. Info sessions begin at 10 am and 2 pm; campus tours routes can be found on either side of the street. -

MIT Opencourseware

MIT OpenCourseWare MIT OpenCourseWare (OCW) is a free and open digital publication of high-quality educational materials organized as courses. Through the Internet, MIT OpenCourseWare has opened MIT’s curriculum and the course materials created by MIT faculty to a global audience of teachers and learners. In the United States and around the world educators use these materials for teaching and curriculum development, while students and self- learners draw upon the materials for self-study or supplementary use. Since the inception of OCW in 2001, more than 8,850 individuals, including nearly 70% of current MIT tenured or tenure-track faculty members, have voluntarily shared their teaching materials through OCW, amassing a collection of many thousands of individual resources, including documents, video, audio, simulations, animations, and sample programming code. An estimated 150 million individuals have accessed these resources, and hundreds of universities around the world have joined MIT in sharing their own course materials freely and openly on the web. Highlights of the Year Publication Status As of June 30, 2013, there were 2,168 courses available on OCW, representing virtually the entire undergraduate and graduate curricula in MIT’s five schools and 33 academic units. Among the live courses on OCW, 742 represent more recent versions of courses that were previously published on OCW. These updated courses have fresh materials, often including new pedagogical approaches. We publish about 40–50 new courses and 60–70 updated courses each year. An update normally requires the complete reassembly of the course site and therefore involves an effort equal to that needed for publishing a new course. -

Department of Chemistry

Department of Chemistry Chemistry is the science of creation, discovery, and understanding at the molecular level. Its achievements continue to fuel advances in other branches of science, in medicine, and in engineering. Major new initiatives in the department include the synthesis of novel molecules to turn sunlight into chemical energy, nitrogen into ammonia, and carbon dioxide into useful reagents, the invention of new tools to investigate complex biological processes including neurochemical signaling, methods to characterize the dynamics of water and the unfolding of proteins in solution, and the design and synthesis of electronic polymers. In academic year 2004, the Chemistry Department continued its strong programs in undergraduate and graduate education. Associated with the department currently are 260 graduate students, 98 postdoctoral researchers, and 104 undergraduate chemistry majors. As of July 1, 2004, the Chemistry Department faculty comprised 31 full‐time faculty members, including 6 assistant professors, 4 associate professors, and 21 full professors, including 1 Institute Professor. Effective July 1, 2003, Professors Jianshu Cao and Andrei Tokmakoff were promoted to associate professor without tenure. In the fall, professors Catherine L. Drennan and Timothy F. Jamison were promoted to associate professor without tenure, to take effect on July 1, 2004. Major Faculty Awards and Honors • Professor Moungi Bawendi was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. • Professor Sylvia T. Ceyer was elected fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science. • Professor Catherine L. Drennan received the Presidential Early Career Award, the Dean’s Educational and Student Advising Award, and the 2004 Edgerton Faculty Award. • Professor Gregory C. Fu received the 2004 E. -

Exploring Palladium-Mediated 11C/12C-Carbonylation Reactions

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Pharmacy 241 Exploring Palladium-Mediated 11C/12C-Carbonylation Reactions PET Tracer Development Targeting the Vesicular Acetylcholine Transporter SARA ROSLIN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6192 ISBN 978-91-513-0136-5 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-332359 2017 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Hall B:21, BMC, Husargatan 3, Uppsala, Friday, 15 December 2017 at 09:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Pharmacy). The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Ph.D. Victor Pike (National Institute of Mental Health, Molecular Imaging Branch). Abstract Roslin, S. 2017. Exploring Palladium-Mediated 11C/12C-Carbonylation Reactions. PET Tracer Development Targeting the Vesicular Acetylcholine Transporter. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Pharmacy 241. 99 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0136-5. The work presented herein describes the utilization and exploration of palladium-mediated incorporations of carbon monoxide and/or [11C]carbon monoxide into compounds and structural motifs with biological relevance. The first part of the thesis describes the design, synthesis and 11C-labeling of prospective PET tracers for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), a target affected in several neurodegenerative diseases. Different parts of the benzovesamicol scaffold were modified in papers I and II to probe the binding to VAChT. The key motif was an amide functional group, which enabled the use of palladium-mediated 11C/12C-carbonylations to synthesize and evaluate two different sets of structurally related ligands. The second part of the thesis describes the exploration of different aspects of palladium- mediated 11C/12C-carbonylation reactions. -

Stanford's Environmental Engineering and Science

Stanford’s Environmental Engineering and Science Program The First Fifty Years by Perry L. McCarty September 1, 2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. i Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................. v Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Early Stanford Activities in Water .................................................................................................. 1 The Post World War II Years ........................................................................................................... 3 Stanford’s Transition ....................................................................................................................... 4 The Water Resources Program ........................................................................................................ 5 The MIT Sanitary Engineering Program ........................................................................................ 6 Stanford’s Graduate Environmental Engineering Program Emerges ............................................. 7 The Early Years ............................................................................................................................... 8 Faculty Evolution ........................................................................................................................... -

Synthesis and Stability Study of a New Bimetallic Complex (Ph3p)3Cumn(CO)5

Asian Journal of Chemistry; Vol. 25, No. 3 (2013), 1597-1599 http://dx.doi.org/10.14233/ajchem.2013.13371 Synthesis and Stability Study of a New Bimetallic Complex (Ph3P)3CuMn(CO)5 1,* 2 3 S.A. AHMAD , C. POTRATZ and M.A. QADIR 1Division of Science and Technology, University of Education, Township Campus, Lahore 54590, Pakistan 2Newmann and Wolfram Laboratories, Department of Chemistry, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA 3Institute of Chemistry, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan *Corresponding author: Tel: +92 333 8255310; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] (Received: 31 December 2011; Accepted: 24 September 2012) AJC-12169 The present work deals with the preparation and stability study of new bimetallic compound related to hetero bimetallic complex (Ph3P)3CuMn(CO)5. Mn2(CO)10 cleaved to KMn(CO)5 in the presence of Na/K alloy. CuCl and KMn(CO)5 reacted with triphenyl phosphine in the presence of THF at -78 ºC. It yielded a mixture of (Ph3P)3CuCl and KMn(CO)5. At 0 ºC, this mixture reacted and produced (Ph3P)3CuMn(CO)5 and Ph3P. New product (Ph3P)3CuMn(CO)5 was found very sensitive to oxidation. It decomposed into (Ph3P), Cu and Mn2(CO)10 under vacuum, at room temperature. Key Words: Bimetallic complex, Cu-Mn complex, Heterogeneous catalysis, Infrared Spectroscopy, Stability, Vacuum. INTRODUCTION acceptors and alkyl halides. It is also used in the synthesis of bi aryl compounds, such as in the Suzuki reaction22. Triphenyl There is considerable interest in hetero bimetallic comp- phosphine binds well to most transition metals, especially those lexes containing lanthanide and transition metals. -

Karl Ziegler Mülheim an Der Ruhr, 8

Historische Stätten der Chemie Karl Ziegler Mülheim an der Ruhr, 8. Mai 2008 Karl Ziegler, Bronzebüste, gestaltet 1964 von Professor Herbert Kaiser-Wilhelm-/Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, Mülheim Kühn, Mülheim an der Ruhr (Foto T. Hobirk 2008; Standort Max- an der Ruhr. Oben: Altbau von 1914 am Kaiser-Wilhelm-Platz. Unten: Plancn k-Institut für Kohlenforschung, Mülheim an der Ruhr). Laborhochhaus von 1967 an der Ecke Lembkestraße/Margaretenplatz (Fotos G. Fink, M. W. Haenel, um 1988). Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker 1 137051_GDCh_Broschuere_Historische_StaettenK2.indd 1 02.09.2009 16:13:26 Uhr Mit dem Programm „Historische Stätten der Chemie“ würdigt die Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker (GDCh) Leistungen von geschichtlichem Rang in der Chemie. Zu den Zielen des Programms gehört, die Erinnerung an das kulturelle Erbe der Chemie wach zu halten und diese Wis- senschaft sowie ihre historischen Wurzeln stärker in das Blickfeld der Öffentlichkeit zu rücken. So werden die Wirkungsstätten von Wissenschaftlerinnen oder Wissen- schaftlern als Orte der Erinnerung in einem feierlichen Akt ausgezeichnet. Außerdem wird eine Broschüre er- stellt, die das wissenschaftliche Werk der Laureaten einer breiten Öffentlichkeit näherbringt und die Tragweite ihrer Arbeiten im aktuellen Kontext beschreibt. Am 8. Mai 2008 gedachten die GDCh und das Max- Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung in Mülheim an der Ruhr des Wirkens von KARL ZIEGLER, der mit seinen bahnbrechenden Arbeiten auf dem Gebiet der organischen Chemie zu den Begründern der metallorganischen