Assessing the Impact of Major In-Town Shopping Centres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abertay University

ABERTAY UNIVERSITY ABERTAY ABERTAY UNIVERSITY 2020 UNDERGRADUATE PROSPECTUS A30 We’ve never been afraid to lead the way. We launched the world’s first computer games degree in 1997. We launched the world’s first ethical hacking degree in 2006. We’re the only university in Scotland to offer a range of accelerated, three-year degrees. And our goal has always been to bridge the gap between university and industry, allowing you to enter a modern jobs market with confidence. We’re enormously proud of our first 25 years as a university, but our city centre campus has been home to an educational institution for well over a century. When the maritime industry was big business in the city – around 100 years ago – a replica of a ship’s bridge was built on the roof of the building. With uninterrupted views of the skies over the River Tay and the North Sea beyond, this replica offered the perfect ‘classroom’ for would-be seafarers to learn how to navigate using the stars. This practical, hands-on approach remains fundamental to what we do at Abertay. Our contemporary, ever-evolving degrees have strong links with industry. So whether it’s work placements, guest lectures or networking events, you’ll be in contact with potential employers from the start. We’re a small university, which means we can get to know the real you. Our students are more than just an ID number. In fact, the close relationship between our inspiring staff and brilliant students is a massive part of what makes Abertay so special. -

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number and Street Name

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number And Street Name Post Code Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMONEY CASTLE ST CASTLE STREET BT53 6JT Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COLERAINE 2 BANNFIELD BT52 1HU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTSTEWART COLERAINE ROAD BT55 7JR Tesco Supermarkets TESCO YORKGATE CENTRE YORKGATE SHOP COMPLEX BT15 1WA Tesco Express TESCO CHURCH ST BALLYMENA EXP 99-111 CHURCH STREET BT43 8DG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMENA LARNE ROAD BT42 3HB Tesco Express TESCO CARNINY BALLYMENA EXP 144 BALLYMONEY ROAD BT43 5BZ Tesco Extra TESCO ANTRIM MASSEREENE CASTLEWAY BT41 4AB Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ENNISKILLEN 11 DUBLIN ROAD BT74 6HN Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COOKSTOWN BROADFIELD ORRITOR ROAD BT80 8BH Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYGOMARTIN BALLYGOMARTIN ROAD BT13 3LD Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ANTRIM ROAD 405 ANTRIM RD STORE439 BT15 3BG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO NEWTOWNABBEY CHURCH ROAD BT36 6YJ Tesco Express TESCO GLENGORMLEY EXP UNIT 5 MAYFIELD CENTRE BT36 7WU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO GLENGORMLEY CARNMONEY RD SHOP CENT BT36 6HD Tesco Express TESCO MONKSTOWN EXPRES MONKSTOWN COMMUNITY CENTRE BT37 0LG Tesco Extra TESCO CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE 8 Minorca Place BT38 8AU Tesco Express TESCO CRESCENT LK DERRY EXP CRESCENT LINK ROAD BT47 5FX Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LISNAGELVIN LISNAGELVIN SHOP CENTR BT47 6DA Tesco Metro TESCO STRAND ROAD THE STRAND BT48 7PY Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LIMAVADY ROEVALLEY NI 119 MAIN STREET BT49 0ET Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LURGAN CARNEGIE ST MILLENIUM WAY BT66 6AS Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTADOWN MEADOW CTR MEADOW -

Dundee Retail Study December 2015

Dundee City Council Dundee Retail Study 2015 December 2015 Roderick MacLean Associates Ltd In association with Ryden 1/2 West Cherrybank, Stanley Road Edinburgh EH6 4SW Tel. 0131 552 4440 Mobile 0775 265 5706 e mail roderick @ rmacleanassociates.com Executive Summary 1. The purpose of the research is to Street. The City Centre has about 87,000 sq m inform preparation of the next Dundee Local gross of comparison and convenience retail Development Plan (LDP2) on key issues floorspace. There is a further 41,600 sq m relating to retailing and town centres. In gross of non-retail services. The vacancy rate Dundee, this covers the network of centres in the City Centre is 17%, which is higher than with a focus on the City Centre, the five District the Scottish average of 10.6% for town Centres and the Commercial Centres (retail centres. Vacant floorspace in the City Centre parks). has increased in recent years. 2. Existing planning policies seek to 8. While there is no known list of protect the vitality and viability of the town multiple retailers with immediate requirements centres and include restrictions on the range of to locate in the City Centre, this is common goods that are sold in the retail parks, together with many other cities, where the market lags with a general presumption against out of behind forecast growth in comparison retail centre retail development. expenditure in the cycle of demand and investment. Prime retail rents in the City 3. A household telephone interview Centre are about £100 per sq ft, which ranks survey covering Dundee and Angus was Dundee at 8th place among rentals in other applied to determine shopping patterns and the town centres/ malls in Scotland. -

Central Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation Area Central Conservation Area Appraisal Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Definition of a Conservation Area 1 1.2 The Meaning of Conservation Area Status 2 1.3 The Purpose of a Conservation Area Appraisal 2 2 Conservation Area Context 4 2.1 Current Boundary 4 2.2 Proposed Boundary Review 6 3 History of the City Centre 7 4 Character and Appearance 10 4.1 Street Pattern and Movement 10 4.2 Views and Vistas 12 4.3 Listed Buildings 12 4.4 Buildings at Risk 13 4.5 Public Realm 14 5 Character Areas 18 5.1 City Core 19 5.2 The North 27 5.3 The Howff 30 5.4 Overgate-Nethergate 32 5.5 Seagate 36 5.6 Southern Edge 38 6 Current and Development Opportunities 40 7 Opportunities For Planning Action 42 8 Opportunities For Enhancement 46 9 Conservation Strategy 46 10 Monitoring And Review 47 Appendices A Current Boundary and Proposed Review Areas B Central Conservation Area Boundary Review C Principal Views and Vistas D Central Conservation Area Buildings at Risk E City Core Character Area F The North Character Area G The Howff Character Area H Overgate-Nethergate Character Area I Seagate Character Area J Southern Edge Character Area 1 Introduction Dundee City Centre is the main hub of activity in Dundee with a vibrant and bustling retail core which permeates throughout the Centre. Dundee Central Conservation Area contains the historic heart of the city, with origins as a small fishing village on the banks of the River Tay, to the City as it stands today, all contributing to its unique character. -

Notice to Creditors to Do So by One Tenth, in Value, of the Company’S Creditors

3848 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE TUESDAY 31 OCTOBER 2006 by the Creditor or by form of proxy, which must be lodged with me at The Insolvency Act 1986 or before the Meeting. INTEGRITY MANAGEMENT & CONSULTING LIMITED A I Fraser, Interim Liquidator (In Liquidation) Tenon Recovery, 10 Ardross Street, Inverness IV3 5NS. (2455/108) Registered Address: 1 Albert Street, Aberdeen AB25 1XX Notice is hereby given in accordance with rule 4.18 of the Insolvency (Scotland) Rules 1986 that, on 10 October 2006 I, Michael J M Reid CA, The Insolvency Act 1986 12 Carden Place, Aberdeen AB10 1UR, was appointed liquidator of Integrity Management & Consulting by order of the Aberdeen. A WDF INTERNATIONAL LIMITED liquidation committee has not been established and I do not propose to (In Liquidation) summon a separate meeting for this purpose unless requested to do so Former Trading Address: Enterprise Centre, Granitehill Road, by one tenth, in value, of the company’s creditors. Aberdeen AB16 7AX All creditors who have not yet lodged a statement of their claim with me, I, Michael J M Reid CA, 12 Carden Place, Aberdeen AB10 1UR hereby are requested to do so in early course. give notice that by interlocutor dated 12 October 2006, the SheriV at Michael J M Reid, CA, Liquidator Aberdeen appointed me interim liquidator of the above company. Meston Reid & Co, 12 Carden Place, Aberdeen AB10 1UR. Notification of the first meeting of creditors of the above company will 24 October 2006. (2460/75) be sent to all creditors in due course pursuant to section 138(3) of the Insolvency Act 1986 and rule 4.12 of the Insolvency (Scotland) Rules 1986. -

Swarovski Boutiques Australia

SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES AUSTRALIA ADELAIDE, GROUND FLOOR, MYER ADELAIDE 22 RUNDLE MALL, 5000 ADELAIDE, RUNDLE MALL PLAZA, 50 Rundle Mall, 5000 BONDI, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE, 500 Oxford Street, 2022 BOORAGOON, GARDEN CITY SHOPPING CENTRE, 125 Riseley Street, 6154 BOURKE STREET, 276 -278 Bourke Street, 3000 BRISBANE, MYER BRISBANE, 91 Queen Street, 4000 BURWOOD, Westfield Burwood, 100 Burwood Rd, 2134 CANBERRA, CANBERRA CENTRE, 148 Bunda St, 2601 CARINDALE, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE, 1151 Creek Road, 4152 CAROUSEL, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE CAROUSEL, 1382 Albany Highway, 6107 CASTLE HILL, CASTLE TOWERS SHOPPING CENTRE, Castle Street, 2154 CHADSTONE, MYER CHADSTONE, Chadstone Shopping Centre, 3148 CHADSTONE, CHADSTONE SHOPPING CENTRE, 1341 Dandenong Road, 3148 CHARLESTOWN, CHARLESTOWN SQUARE, 30 Pearson St, 2290 CHATSWOOD, LEVEL 4, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE, 1 Anderson Street, 2067 CHERMSIDE, WESTFIELD CHERMSIDE, Gympie Rd & Hamilton Rd, 4032 CLAREMONT, CLAREMONT QUARTER, 9 Bayview Terrace, 6010 DONCASTER, LEVEL 1, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE, 619 Doncaster Road, 3108 DONCASTER, MYER DONCASTER, WESTFIELD DONCASTER, 619 Doncaster Road, 3108 EAST MAITLAND, STOCKLAND GREENHILLS, 1 Molly Morgan Drive, 2323 EASTGARDENS, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE, 152 Bunnerong Road, 2036 EASTLAND, EASTLAND SHOPPING CENTRE, 171-175 Maroondah Highway, 3134 EMPORIUM, THE EMPORIUM MALL, 269-321 Lonsdale Street, 3000 ERINA, ERINA SHOPPING CENTRE, 620-658 Terrigal Drive, 2250, NSW FOUNTAIN GATE, WESTFIED SHOPPING CENTRE, 352 Princes Hwy, 3805 GARDEN CITY, WESTFIELD SHOPPING CENTRE GARDEN CITY, Cnr Logan & Kessels Roads, 4122 GEELONG, GROUND LEVEL, WESTFIELD BAY CITY, 95 Malop Street, 3220 HIGHPOINT, HIGHPOINT SHOPPING CENTRE, 120-200 Rosamond Road, 3032 HORNSBY, Westfield Hornsby, 236 Pacific Highway, 2077 INDOOROOPILLY, INDOOROOPILLY SHOPPING CENTRE, 322 Moggill Road, 4068 KNOX CITY, KNOX CITY SHOPPING CENTRE. -

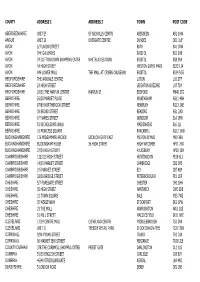

Store Name Address 1 Address 2 Town Postcode FROGMORE

Store Name Address 1 Address 2 Town Postcode FROGMORE ABERGAVENNY1 CIBI WALK FROGMORE STREET ABERGAVENNY NP7 5AB ABERYSTWYTH 36 TERRACE ROAD ABERYSTWYTH SY23 2AB ST NICHOLAS ABERDEEN UNIT E5 ST NICHOLLS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB1 1HW ALDERSHOT 63/68 WELLINGTON CENTRE VICTORIA RD ALDERSHOT GU11 1DB UNION ST ABERDEEN 408/412 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1PD AIRDRIE 60-62 GRAHAM STREET AIRDRIE ML6 6BU ALDRIDGE 44 THE SQUARE ALDRIDGE WS9 8QS ALNWICK 56 BONDGATE WITHIN ALNWICK NE66 1JD ACCRINGTON 14 CORNHILL ACCRINGTON BB5 1EX ALTON UNITS 6/7 WESTBROOK WALK ALTON GU34 1HZ ALTRINCHAM 8/12 GEORGE STREET ALTRINCHAM WA14 1SF ANDOVER 31 HIGH STREET ANDOVER SP10 1LJ ARGYLE STREET 53-55 ARGYLE STREET GLASGOW G2 8AH ARNOLD 24-26 FRONT STREET ARNOLD NG5 7EL ARBROATH 196 HIGH STREET ARBROATH DD11 1HY ASHFORD 70/72 HIGH STREET ASHFORD TN24 8TB ASHTON UNDER LYNE UNIT 30 ARCADE SHOPPING CENTRE ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE OL6 7JE AYLESBURY 27/29 HIGH STREET AYLESBURY HP20 1SH AYR 198/200 HIGH STREET AYR KA7 1RH BALHAM 176 HIGH ROAD BALHAM SW12 9BW BANBURY 23/24 CASTLE CENTRE BANBURY OX16 8UE BANCHORY 33 HIGH STREET BANCHORY AB31 5TJ MARKET BANGOR BKS THE MARKET HALL HIGH STREET BANGOR LL57 1NY BARNSLEY 11/13 CHEAPSIDE BARNSLEY S70 1RQ BARNSTAPLE 76 HIGH STREET BARNSTAPLE EX31 1HP BARROW 38-42 PORTLAND WALK BARROW-IN-FURNESS LA14 1DB BASINGSTOKE 5/7 OLD BASING MALL BASINGSTOKE RG21 1AW BATH UNION ST 6/7 UNION STREET BATH BA1 1RW BEACONSFIELD 11 THE HIGHWAY STATION ROAD BEACONSFIELD HP9 1QD BEAUMONT LEYS 18 BRADGATE MALL BEAUMONT LEYS SHOPPING CENTRELEICESTER LE4 1DE BECKENHAM -

1 REPORT to PARISH GROUPING DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE By

REPORT TO PARISH GROUPING DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE by Ian McIver, Community Outreach Worker CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction........................................................................................................2 Chapter 2 Parish profiles.....................................................................................................6 Chapter 3 Church profiles.................................................................................................12 Chapter 4 Mission-shaped Parish (traditional church in a changing context) by Paul Bayes and Tim Sledge...........................................................15 Chapter 5 The Road to Growth (towards a thriving Church) by Bob Jackson.................. 23 Chapter 6 Vision & strategy..............................................................................................31 Chapter 7 Growing churches.............................................................................................35 Chapter 8 Possible initiatives by the Parish Grouping/churches.......................................39 Chapter 9 Opportunities to volunteer................................................................................48 Chapter 10 Fresh expressions of church.............................................................................51 Chapter 11 What are other city churches up to?.................................................................57 Chapter 12 Project ideas.....................................................................................................60 -

2012 -2013 Official Match Day Programme

2012 - 2013 Official Match day Programme TAYPORT F.C. THE CANNIEPAIRT,SHANWELL ROAD, TAYPORT D06 9DX TODAY'S TEAMS TEL. 01382 553670, NEWSLINE 01382 552755 • www.tayportfc.org DALKEITH THISTLE Colours - Red Shirts, Black Shorts, Red Socks - Change - White Shirts, Black Shorts , White Socks TAYPORT FOUNDED 1947 (as amateurs) 1990 (as juniors) from ROLL OF HONOUR from II I If • I .. : •• 111 I II I 11 · I II I , II t: 1 lain ROSS Ross COMBE Runners-up 1992/93, 1996/ 97, 2003 /04 20 Neal FERRIE Grant GAVIN East Super League Cha mp ions I ersport Shield Winners 1990/ 9 1, 1993/ 94 2 Colin McNAUGHT Thomas WATERS 2002 /03, 2005/ 06 D.J.Loing Trophy Winners 1997 /98 3 Gary ROBERTSON Jay HUNTER Runners -up 2003/ 04, 2004 /05 ge Cup 1999/2 000, 2000/ 01, 2002/ 03, 2006 / 07 4 Barrv DONACHIE David LIDDLE EastPrem ie r League Champion s 2009 / 10 D.J. Laing League Cup 2001 /02 Tayside League Division I/Prem ier League Champions Croig Stephen Trophy Winners 1990/ 91, 1991 /92, 1993/94, 5 Paul THOMSON Kevin MURRAY 199 1/ 92, 1992/ 93, 1993/ 94, 1994/ 95, 1995/ 96, 1998799 1995/96, 1997/98, 1998/99, 2000/ 01, 2001/ 02 6 John TONNER David MORRIS 1999/2 000 , 2000/200 1, 200 1/2002 (Association's Top Scoring Club) Kr is ROLLO Tayside League Division 2 Champ ions 1990/ 9 1 Albert Hersche ll Trophy Winners 1990/ 91, 1991/ 92, 1992/ 93, 7 Lloyd RICHARDSON Tayside/No rth Regiona l Cup 1993/ 94, 200 1/02 8 Steven McPHEE Kenny FISHER (variously sponsored by Zamoyski, North End Centen 1994/ 95, 1995/96, 1998/99, 9 Simon MURRAY Darren FLYNN Concept Group , NCR and The Dugout) 1999/2000 , 2000 / 01, 2001/ 02 10 Andy McDONALD Scott McNAUGHTON Winners 1991/ 92, 1994 / 95, 1999/2000 , 200 1/ 02, 2002/03, ~mier Cha mpion s v Division I Champions Charity Trophy) 2003 / 04, 2004/ 05 David Scott Cup 1995/ 96 11 Jamie MACKIE Steven PUDLESKI . -

WHS HS Store List

COUNTY ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 TOWN POST CODE ABERDEENSHIRE UNIT E5 ST NICHOLLS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB1 1HW ANGUS UNIT 18 OVERGATE CENTRE DUNDEE DD1 1UF AVON 6/7 UNION STREET BATH BA1 1RW AVON THE GALLERIES BRISTOL BS1 3XB AVON 24 CLIFTON DOWN SHOPPING CNTRE WHITELADIES ROAD BRISTOL BS8 2NN AVON 44 HIGH STREET WESTON SUPER MARE BS23 1JA AVON 049 LOWER MALL THE MALL AT CRIBBS CAUSEWAY BRISTOL BS34 5GG BEDFORDSHIRE THE ARNDALE CENTRE LUTON LU1 2TF BEDFORDSHIRE 23 HIGH STREET LEIGHTON BUZZARD LU7 7DN BEDFORDSHIRE 29/31 THE HARPUR CENTRE HARPUR ST BEDFORD MK40 1TG BERKSHIRE 26/28 MARKET PLACE WOKINGHAM RG11 4AH BERKSHIRE 87/89 NORTHBROOK STREET NEWBURY RG13 1AE BERKSHIRE 39 BROAD STREET READING RG1 2AD BERKSHIRE 6 THAMES STREET WINDSOR SL4 1PW BERKSHIRE 51 NICHOLSON'S WALK MAIDENHEAD SL6 1LL BERKSHIRE 10 PRINCESS SQUARE BRACKNELL RG12 1XW BUCKINGHAMSHIRE 126 MIDSUMMER ARCADE SECKLOW GATE EAST MILTON KEYNES MK9 3BA BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BUCKINGHAM HOUSE 36 HIGH STREET HIGH WYCOMBE HP11 2AR BUCKINGHAMSHIRE 27/29 HIGH STREET AYLESBURY HP20 1SH CAMBRIDGESHIRE 122/123 HIGH STREET HUNTINGDON PE18 6LG CAMBRIDGESHIRE 14/15 MARKET STREET CAMBRIDGE CB2 3PE CAMBRIDGESHIRE 3-5 MARKET STREET ELY CB7 4BP CAMBRIDGESHIRE 32/36 BRIDGE STREET PETERBOROUGH PE1 1DP CHESHIRE 5/7 FOREGATE STREET CHESTER CH1 1HH CHESHIRE 35 HIGH STREET NANTWICH CW5 5DB CHESHIRE 15 TOWN SQUARE SALE M33 7WZ CHESHIRE 35 MERSEYWAY STOCKPORT SK1 1PW CHESHIRE 18 THE MALL WARRINGTON WA1 1QE CHESHIRE 51 MILL STREET MACCLESFIELD SK11 6NE CLEVELAND 17/19 CENTRE MALL CLEVELAND CENTRE MIDDLESBROUGH TS1 2NR -

Your Local Golf Magazine for Grass Roots Golfers

North Your local golf magazine for grass roots golfers Local golf news for golfers in Scotland, Northern England and North Wales Golf North Spring/Summer 2016 Use your smart phone to scan the code or go to our website. www.golfnorth.co.uk Pure Perfection ... where the SCOTLAND’s past and present meets to GOLF COAST create golfing excellence GOLF EAST LOTHIAN NEW WEBSITE - ONLINE BOOKINGS NOW TAKEN East Lothian provides an inspirational setting for excellent food and drink and award-winning golf, and with 22 courses it may well be the highest attractions. concentration of links golf courses in the world. Just Scotland’s Golf Coast has a diverse offering of a half-hour drive East of Edinburgh, this is a jewel in accommodation, providing the perfect opportunity Scotland’s crown as the Home of Golf: stretching to rest, relax and unwind before another round of through 30 miles of stunning coastline, golden golf. You will be spoiled for choice with 5-star luxury beaches and rolling countryside, this is a golfing hotels, family-run bed and breakfasts, self-catering paradise to suit all standards, individual tastes and apartments or even centuries-old stately homes budgets. Known as the sunniest and driest part of all on offer. No matter where you choose to stay Host to the 2015 Aberdeen Scotland, and coupled with links conditions, it is you are guaranteed a very warm welcome and an open for business throughout the year, with a warm authentic experience. welcome awaiting every visitor. No golfing break can be enjoyed on an empty It all begins in 1672 at the world’s oldest continually stomach: East Lothian is renowned as ‘The Garden played golf course at Musselburgh Links; featuring of Scotland’ with the very best locally-sourced, many familiar names such as Gullane and North seasonal produce available throughout. -

To the Basement Storage

> WELL LOCATED CITY CENTRE RETAIL UNIT > FRONTING MAIN PEDESTRIAN THOROUGHFARE BETWEEN OVERGATE CENTRE AND V & A / RAILWAY STATION > BRIGHT RETAIL AREA WITH STAFF KITCHEN AND W.C. FACILITIES > CONCRETE STAIR DOWN TO THE BASEMENT STORAGE > 100% RATES RELIEF AVAILABLE UNDER SMALL BUSINESS BONUS SCHEME TO LET 30 UNION STREET, DUNDEE, DD1 4BE CONTACT: Scott Robertson – [email protected] Gerry McCluskey - [email protected] – 01382 878005 www.shepherd.co.uk 30 UNION STREET, DUNDEE, DD1 4BE 30 Union Street, Dundee, DD1 4BE LOCATION Dundee, Scotland's fourth largest City with a resident population The property has a modern retail shop front with side entrance of circa 150,000 persons (National Records of Scotland) is located providing pavement level access to an open retail area with staff on the East coast of Scotland approximately mid-way between accommodation at the rear. Aberdeen (circa 105 kilometres (65 miles) to the north) and Edinburgh (circa 96 kilometres (60 miles) to the south). The previous tenants fit out remains insitu. The city benefits from excellent transport links, with daily flights There is a concrete stair down to good basement storage. to London (City Airport) and Belfast (from 2020) and rail services into London (Kings Cross). ACCOMMODATION m2 ft2 The ongoing Dundee Waterfront £1 Billion re-development has Ground 41.61 448 attracted major investment into the city with the opening of the V & A Museum in September 2018, significantly contributing to Basement 40.53 436 Dundee’s growth as a major business and tourism centre. TOTAL 82.14 884 Union Street is a busy secondary retail location situated just south of Overgate Shopping Centre and forms the principle The foregoing areas have been calculated on a net internal pedestrian link between the City Centre and the central area basis in accordance with the RICS Property waterfront redevelopment area where the V & A Museum and Measurement Guidance (2nd Edition).