The Tunisian Local Governance Performance Index: Selected Findings on Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Spécialité Economie Rurale Et Développement

REPUBLIQUE TUNISIENNE MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE, MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT DES RESSOURCES HYDRAULIQUES ET SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE DE LA PECHE SCIENTIFIQUE INSTITUT NATIONAL AGRONOMIQUE DE TUNISIE Ecole Doctorale Sciences et Techniques de L’Agronomie et de l’Environnement THESE DE DOCTORAT EN SCIENCES AGRONOMIQUES Spécialité Economie Rurale et Développement Institutional arrangements and sustainability of the dairy value chain in Bizerte (Tunisia) Soutenue publiquement par Meriem MSADDAK 11 janvier 2020 à INAT Devant le jury composé de M. Nizar MOUJAHED, Professeur, INAT Président M. Lokman ZAIBET, Professeur, Université Sultan Qaboos Directeur de thèse M. Houcine BOUGHANMI, Maitre de conférences, Université Sultan Qaboos Rapporteur Mme Sonia BOUDICHE, Maitre de conférences, ESIAT Rapporteur M. Slim ZEKRI, Professeur, Université Sultan Qaboos Examinateur Acknowledgement I would like to express my gratitude to those thanks to whom this thesis was able to be developed and who, for this purpose, have generously provided me with their support. First of all, I would like to thank my thesis director, Pr Lokman Zaibet, university professor, who trusted on me; gave me the opportunity to conduct the work of my choice under his supervision; patiently rectified my writings; always gave me the benefit of his experience. He teaches me how to think outside the box and always had the right words in mind to motivate me and inspire me to go ahead with my thinking. When you know the number of publications that are yours, you determine the opportunity that was mine. My study owes him a lot. In short, Pr Zaibet, is a person for whom I have a great deal of wonder, esteem and respect. -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

The National Sanitation Utility

OFFICE NATIONAL DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT (THE NATIONAL SANITATION UTILITY) 32,rue Hédi Nouira 1001 TUNIS Tel.:710 343 200 – Fax :71 350 411 E-mail :[email protected] Web site :www.onas.nat.tn ANNUAL REPORT 2004 O.N.A.S.IN BRIEF MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BOARD Khalil ATTIA President of the E. B. 1.Establishment Maher KAMMOUN Prime Ministry Noureddine BEN REJEB Ministry of Agriculture The National Sanitation Utility (O.N.A.S.) is a public company of an and Hydraulic Resources industrial and commercial character,serving under the authority of the Mohamed BELKHIRIA Ministry of the Interior and Local Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development, and Development enjoying the status of a civil entity and financial independence. It was Moncef MILED Ministry of Development and established by Law N° 73/74, dated August 1974, and entrusted with International Cooperation the management of the sanitation sector. Rakia LAATIRI Ministry of Agriculture and The Law establishing O.N.A.S. was amended pursuant to Law N° Hydraulic Resources 41/93, dated 19 April 1993, which promoted the Utility from the sta- Mohamed Tarek EL BAHRI Ministry of Equipment, Housing tus of a networks and sewers management authority to the status of and Land Use Planning a key operator in the field of protection of the water environment. Abderrahmane GUENNOUN National Environment Protection Agency (ANPE) 2.O.N.A.S.Mission: Abdelaziz MABROUK National Water Distribution Utility (SONEDE) •Combating all forms of water pollution and containing its sources; Slah EL BALTI Municipality of Ariana •Operation, management and maintenance of all sanitation facilities in O.N.A.S. -

Algeria Kazakhstan

LONDON COLOGNE BRUSSELS PARIS MILAN ANKARA MADRID TUNIS TOKYO GEOGRAPHY DOHA ie TUNISIA tn ECONOMIC o B e FIPA-Ankara • [email protected] d FIPA-Brussels • [email protected] e f NORVEGE l FIPA-Cologne • [email protected] Foreign Investment Promotion Agency FIPA-Doha • [email protected] o INVEST IN TUNISIA FIPA-London • [email protected] G Rue Salaheddine El Ammami Centre Urbain Nord, 1004 Tunis-Tunisia FIPA-Madrid • [email protected] Tel.: (216) 71 752 540 • Fax: (216) 71 231 400 FIPA-Milan • [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] FIPA-Paris •R.U [email protected] FIPA-Tokyo • [email protected] www.investintunisia.tn NORTH ESTONIE SEA DENMARK A LATVIA E COPENHAGEN S C 1 UNITED KINGDOM 3H30 TI LITHUANIA BAL LOCATION GERMANY POLAND PAYS-BASAMSTERDAM BELARUS GEOGRAPHICAL OF IRELAND LONDON 2H15 DUSSELDORF 2H22 TUNISIA 2H17 BRUSSELS 2H00 COLOGNE BELGIUM Capital Tunis LUX. 2H05 CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA PARIS ORLY/CDG FRANKFORT VIENNA UKRAINE Area 162 155 Km2 1H46/2H08 1H59 MUNICH 1H54 MOLDOVA NANTE KAZAKHSTAN SWITZERLANDGENEVA 1H47 North Africa, 140 km 2H14 ZURICH AUSTRIA Bay 1H30 HUNGARY from Italy, 1300 km FRANCE 1H40SLOV.VENICE ROMANIA Situation of Biscay of coastline along LYON MILAN 1H15 BELGRADE C BORDEAUX 1H23 1H21 BOLOGNA BOSNIA. 1H30 A the Mediterranean 1H43 S 1H17 P TOULOUSE MARSEILLE I S.M SERBIA BLACK SEA E Mediterranean, 1H37 1H23 NICE ITALY MONTENEGRO N UZBEKISTAN VATICANROME BULGARIA GEORGIA Climat -

Development and Democracy in the Tunisian Revolution

The Process of Revolutionary Protest: Development and Democracy in the Tunisian Revolution Christopher Barrie∗ July 30, 2021 Abstract Revolutionary protest rarely begins life as democratic or revolutionary. Instead, it grows in a process of positive feedback, incorporating new constituencies and generating new demands. If protest is not revolutionary at its onset, theory should reflect this and be able to explain the endogenous emergence of democratic demands. In this article, I combine multiple data sources on the 2010-11 Tunisian Revolution, including survey data, an original event catalogue, and field interviews. I show that the correlates of protest occurrence and participation change significantly during the uprising. Using the Tunisian case as a theory-building exercise, I argue that the formation of protest coalitions is essential, rather than incidental, to democratic revolution. ∗Christopher Barrie is Lecturer in Computational Sociology at the University of Edinburgh. Correspon- dence to: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction Mass mobilization is now a central pillar in in the theoretical and empirical scholarship on democratization. But while political transition to democracy can be marked in time—by the ouster of an authoritarian or the holding of elections—mass mobilization constitutes a pro- cess. A large body of empirical work in the democratization literature nonetheless treats revolutionary protest, or revolutionary protest participation, as discrete, unitary events amenable to cross-sectional forms of analysis. A separate body of work, particular to the formal modelling tradition, incorporates elements of endogeneity and process but assumes common thresholds governing participation dynamics, thereby again conceiving of revolu- tionary protest as unitary. In this article I propose that this ontology is wrongheaded; protest is rarely revolutionary at its onset and the goals and orienting demands of protest waves can be generated in the context of contention. -

Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region In

Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in Republic Project Republic of Tunisia Ministry of Development, Investment, and International Cooperation (MDICI), South Development Office (ODS) Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia Final Report Part 1 Current Status of Tunisia and the Southern Region Final Report Part 1 November, 2015 JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc. INGÉROSEC Corporation EI JR 15 - 201 Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in Republic Project Republic of Tunisia Ministry of Development, Investment, and International Cooperation (MDICI), South Development Office (ODS) Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia Final Report Part 1 Current Status of Tunisia and the Southern Region Final Report Part 1 November, 2015 JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc. INGÉROSEC Corporation Italy Tunisia Location of Tunisia Algeria Libya Tunisia and surrounding countries Legend Gafsa – Ksar International Airport Airport Gabes Djerba–Zarzis Seaport Tozeur–Nefta Seaport International Airport International Airport Railway Highway Zarzis Seaport Target Area (Six Governorates in the Southern -

Oojec FRBM S ) 0285 and AWDLIN

RURAL DEVEIME 0285oOJEC AND AWDLIN FRBM S ) Final Report Arthur J. Dommen Agricultural Economist USAID/RM (Mak+r) September 4, 1979 fICE M RANDUM T: 'Mr.H. R. Slusser, Acting General Development Offieer FROM: W.r Arthur J. Donmien, (Maktear) IWTE: September 4, 1979 SUBJECT: Submission of Final Report In view of the immdnent compltion on schedule of Project 0285, I am transmitting to you herewith a copy of my Final Report on thhi project, prepared at the request of Mr. Robert W. Beckman, Acting Directra VMID/Tunisia at the time. This was done an Ewn time. As indicated in the Introduction, the views expressed herein aen entirely nW own and do not engage USAID in Any vay. A copy of this report will be placed in the RrA files for tio future reference of those to whOm it nmy prove useful, as Hirsch's final report on the project was to me. In the smet spirit, I am die tributAnW cops only to Amrercam persons wbn have been In the project &rMe 1. TABLE IF CONTENTS Introduction Phge 2 I. The Project Area and Its People 3 II. Project History 6 III. Operating in Maktar 15 IV. Project Components 25 (a) CARE-Medico Wells 25 Artificial Catchment Basins 31 Genie Rural Wells and Springs 34 Hababsa Water System 34 SONEDE Water Distribution Systems 36 Road Building 37 Agricultural Equipment and Plaktar Depot; Vehicles 39 Apiculture 40 Range Management 41 Medicago 42 Extension Improvement 44 Arboriculture 45 Sheep Dipping Vats 46 SCF Com=nity Development 49 Social Projects 53 Participant Travel and Consultants 53 Data Collection 53 (b) U.S. -

Investment Opportunities in Inland Areas of Tunisia

Investment Opportunities in Inland Areas of Tunisia Investment Opportunities in Inland Areas of Tunisia Regional development in particular in inland areas within the next few years will be one of the major concerns of public authorities. To attract investment in these areas the regional development policy will be focused primarily on five fields: • establishing good regional governance; • developing infrastructure (roads, highways, railway etc.); • strengthening financial and tax incentives; • Improving the living environment; • promoting decentralized international cooperation. Ind industries Leather Ceramics ‐ and Industries electric IT Tourism Transport Manufacturing and Materials Agriculture Handicrafts Agribusiness Garment Chemical Various Building Textile Mechanical Gafsa X X X X X X X Kasserine X X X X X Jendouba X X X X X Siliana X X X X X Kef Beja X X X X X X X Kairouan X X X X X X X X Kebili X X X Tataouine X X X X Medenine X X X X X X Tozeur X X X X Sidi Bouzid X X X X X Gabes X X X X X X X SIDI BOUZID Matrix of Opportunities and Potentials in the Governorate of Sidi Bouzid Sectors Opportunities and potentials Benefits and resources Agriculture and ‐ The possibility to specialize in the production of ‐ The availability of local produce Agribusiness organic varieties in both crops and livestock activity such as meat of the indigenous type (honey, olive oil, sheep Nejdi, camelina Nejdi (Barbarine) ; (Mezzounna), etc..); ‐ soil conditions are most conducive ‐ production of certain tree crops in irrigated good and ground water is -

September 2020, Pp.11-24 ISSN Online: 1737-9350; ISSN Print: 1737-6688, Open Access Scientific Press International Limited

Journal International Sciences et Technique de l’Eau et de l’Environnement ISSN Online: 1737-9350 ISSN JOURNALPrint: 1737-6688, Open Access Volume (V) - Numéro 2 - Décembre 2020 INTERNATIONAL Septembre2020 – Sciences et Techniques de l’Eau et de l’Environnement ISSN Online: 1737-9350 ISSN Print: 1737-6688 Open Access Volume (V ) - Numéro 1 – Septembre 2020 : Volume: (V), Numéro 1 Eau-Climat’2020 de l’Environnementde Ressources en Eau et Changement Climatique Rédacteur en Chef : Pr Noureddine Gaaloul Publié par : International Sciences etTechniques l’Eau de et Journal _________________________________________________________________________Page 1 Journal International Sciences et Technique de l’Eau et de l’Environnement L’AssociationInternational Scientifique Journal Water Sciences andet Environment Technique Technologies pour l’Eau et V(v), N°1 - / V(v), Issue 1 – Sepc. 2020 Open Access - http://jistee.org/volume-v-2020/ l’Environnement en Tunisie (ASTEETunisie) Journal International Sciences et Technique de l’Eau et de l’Environnement ISSN Online: 1737-9350 ISSN Print: 1737-6688, Open Access Volume (v) - Numéro 1 - Septembre 2020 _________________________________________________________________________Page 2 Journal International Sciences et Technique de l’Eau et de l’Environnement International Journal Water Sciences and Environment Technologies V(v), No. 1 - / V(v), Issue 1 – Sep. 2020 Open Access - jistee.org/volume-v-2020/ Journal International Sciences et Technique de l’Eau et de l’Environnement ISSN Online: 1737-9350 ISSN Print: 1737-6688, Open Access Volume (v) - Numéro 1 - Septembre 2020 "وجعْلنا ِمن الْماء ُكل شيٍء ح ٍي" َ َ َ َ َ َ َ ْ َ سورة اﻷنبياء أية 30 Et fait de l’eau toute chose vivante (Al-Anbiya 30) _________________________________________________________________________Page 3 Journal International Sciences et Technique de l’Eau et de l’Environnement International Journal Water Sciences and Environment Technologies V(v), No. -

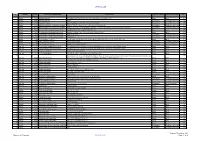

Annex I List of Ongoing and Completed Projects

Support to DG Environment for the development of the Mediterranean De-pollution Initiative “Horizon 2020” Review of Ongoing and Completed Activities ANNEX Prepared for DG Environment European Commission December 2006 Contract No 070201/2006/436133/MAR/E3 LDK-ECO S.A. Environmental Consultants Off 21 Thivaidos str. Athens GR 145 64 Greece Tel: +30 210 6255300 Fax: +30 210 6254871 Web: www.ldkeco.gr E-mail: [email protected] Support to DG Environment for development of the Mediterranean De-pollution Initiative “HORIZON 2020” No 070201/2006/436133/MAR/E3 Annex I List of ongoing and completed projects LDK ECO SA Support to DG Environment for development of the Mediterranean De-pollution Initiative “HORIZON 2020” No 070201/2006/436133/MAR/E3 COUNTRY: ALGERIA Programme/ Country Field of Activity Project ID Project Title Project Description Project Location Implementing agency Beneficiary Budget Donor/ Lender National Duration Starting Date End Date Implementation Actors (urban wastewater, Contribution/ status municipal solid waste, Local (ongoing or industrial emissions) Financing completed) National Algeria urban wastewater Rehabilitation of treatment plants of Tipaza Rehabilitation of treatment plants of Tipaza and Tiemcen Tipaza and public funds ongoing Program of and Tiemcen Tiemcen Economic Development National Algeria urban wastewater Treatment plant (new) of Jijel, Oran, Skikda Treatment plant (new) of Jijel, Oran, Skikda and Annaba (El Bouni) Jijel, Oran, Skikda public funds ongoing Program of and Annaba (El Bouni) and Annaba (El Economic