Development and Democracy in the Tunisian Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yemen Sheila Carapico University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2013 Yemen Sheila Carapico University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Carapico, Sheila. "Yemen." In Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, edited by Paul Amar and Vijay Prashad, 101-121. New Delhi, India: LeftWord Books, 2013. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yemen SHEILA CARAPICO IN FEBRUARY 2011, Tawakkol Karman stood on a stage outside Sanaa University. A microphone in one hand and the other clenched defiantly above her head, reading from a list of demands, she led tens of thou sands of cheering, flag-waving demonstrators in calls for peaceful politi cal change. She was to become not so much the leader as the figurehead ofYemen's uprising. On other days and in other cities, other citizens led the chants: men and women and sometimes, for effect, little children. These mass public performances enacted a veritable civic revolution in a poverty-stricken country where previous activist surges never produced democratic transitions but nonetheless did shape national history. Drawing on the Tunisiari and Egyptian inspirations as well as homegrown protest legacies, in 2011 Yemenis occupied the national commons as never before. -

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Tunisia 2019 Human Rights Report

TUNISIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tunisia is a constitutional republic with a multiparty, unicameral parliamentary system and a president with powers specified in the constitution. During the year the country held parliamentary and presidential elections in the first transition of power since its first democratic elections in 2014. On October 6, the country held open and competitive parliamentary elections that resulted in the Nahda Party winning a plurality of the votes, granting the party the opportunity to form a new government. President Kais Saied, an independent candidate without a political party, came to office on October 23 after winning the country’s second democratic presidential elections. On July 25, President Caid Essebsi died of natural causes and power transferred to Speaker of Parliament Mohamed Ennaceur as acting president for the three months prior to the election of President Saied on October 13. The Ministry of Interior holds legal authority and responsibility for law enforcement. The ministry oversees the National Police, which has primary responsibility for law enforcement in the major cities, and the National Guard (gendarmerie), which oversees border security and patrols smaller towns and rural areas. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Significant human rights issues included reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings, primarily by terrorist groups; allegations of torture by government agents, which reportedly decreased during the year; arbitrary arrests and detentions of suspects under antiterrorism or emergency laws; undue restrictions on freedom of expression and the press, including criminalization of libel; corruption, although the government took steps to combat it; societal violence and threats of violence targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons; and criminalization of consensual same-sex sexual conduct that resulted in arrests and abuse by security forces. -

Protest and State–Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

SIPRI Policy Paper PROTEST AND STATE– 56 SOCIETY RELATIONS IN October 2020 THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Ambassador Ramtane Lamamra (Algeria) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Protest and State– Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa SIPRI Policy Paper No. 56 dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil October 2020 © SIPRI 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 Figure 1.1. Classification of countries in the Middle East and North Africa by 2 protest intensity 2. State–society relations in the Middle East and North Africa 5 Mass protests 5 Sporadic protests 16 Scarce protests 31 Highly suppressed protests 37 Figure 2.1. -

1 Examining Opposition Movements and Regime Stability in Tunisia And

Examining Opposition Movements and Regime Stability in Tunisia and Jordan during the Arab Spring: A Political Opportunities Approach By Paul Meuse MPP Essay Submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Policy Presented June 20th, 2013 1 Master of Public Policy Essay of Paul Meuse presented on June 20th, 2013 APPROVED: Sarah Henderson Sally Gallagher Steven Ortiz Paul Meuse, Author 2 Introduction The Arab Spring can be described as a revolutionary wave of civil uprisings in the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region that has led to regime change in four countries (Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen), an ongoing, violent civil war (Syria) as well as major and minor protests among most countries in the region and some beyond. As events continue to unfold over two years later, much of the academic literature examining the Arab Spring has been centrally focused on questions as to a) what factors caused the Arab Spring and b) why outcomes among countries touched by the Arab Spring varied so starkly. Of the scholarship addressing the latter question, most of the literature to date has emphasized the importance of specific external/internal “top down” factors that explain diverging pathways among MENA countries, often neglecting to explore the influence of the “masses” in driving different outcomes. Moreover among those “bottom-up” accounts of the Arab Spring that do incorporate a role for the masses, the focus has generally been on “diffusion processes” across borders, or the utilization of new media, processes that only affected regime breakdown/stability indirectly. -

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark The Course consists of 8 lectures, 16 presentation-led seminars and 4 gobbets classes GENERAL READING Jonathan Sperber, The European Revolutions, 1848-1851 (Cambridge, 1994) Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Oxford, 2001) Priscilla Smith Robertson, The Revolutions of 1848, a social history (Princeton, 1952) Michael Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (London, 2009) SOCIAL CONFLICT BEFORE 1848 (i) The ‘Galician Slaughter’ of 1846 Hans Henning Hahn, ‘The Polish Nation in the Revolution of 1846-49’, in Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform, pp. 170-185 Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford, 2010), esp. chapters 3 & 4 Thomas W. Simons Jr., ‘The Peasant Revolt of 1846 in Galicia: Recent Polish Historiography’, Slavic Review, 30 (December 1971) pp. 795–815 (ii) Weavers in Revolt Robert J. Bezucha, The Lyon Uprising of 1834: Social and Political Conflict in the Early July Monarchy (Cambridge Mass., 1974) Christina von Hodenberg, Aufstand der Weber. Die Revolte von 1844 und ihr Aufstieg zum Mythos (Bonn, 1997) *Lutz Kroneberg and Rolf Schloesser (eds.), Weber-Revolte 1844 : der schlesische Weberaufstand im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Publizistik und Literatur (Cologne, 1979) Parallels: David Montgomery, ‘The Shuttle and the Cross: Weavers and Artisans in the Kensington Riots of 1844’ Journal of Social History, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Summer, 1972), pp. 411-446 (iii) Food riots Manfred Gailus, ‘Food Riots in Germany in the Late 1840s’, Past & Present, No. 145 (Nov., 1994), pp. 157-193 Raj Patel and Philip McMichael, ‘A Political Economy of the Food Riot’ Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 32/1 (2009), pp. -

The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and Their Impact on Israeli-Palestinian Peace Efforts

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-25-2018 The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and their Impact on Israeli-Palestinian Peace Efforts Daniel Bucksbaum Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Bucksbaum, Daniel, "The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and their Impact on Israeli- Palestinian Peace Efforts" (2018). Honors Theses. 3009. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/3009 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and their Impact on Israeli- Palestinian Peace Efforts By Daniel Bucksbaum A thesis submitted to the Lee Honors College Western Michigan University April 2018 Thesis Committee: Jim Butterfield, Ph.D., Chair Yuan-Kang Wang, Ph.D. Mustafa Mughazy, Ph.D. Bucksbaum 1 Table of Contents I. Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 II. Source Material……………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 III. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 IV. Historical Context for the Two-State Solution………………………………………………………...6 a. Deeply Rooted and Ideological Claims to the Land……………………………………………….…..7 b. Legacy of the Oslo Accords……………………………………………………………………………………….9 c. Israeli Narrative: Why the Two-State Solution is Unfeasible……………………………………19 d. Palestinian Narrative: Why the Two-State Solution has become unattainable………..22 e. Drop in Support for the Two-State Solution; Negotiations entirely…………………………27 f. -

JULIAN ASSANGE: When Google Met Wikileaks

JULIAN ASSANGE JULIAN +OR Books Email Images Behind Google’s image as the over-friendly giant of global tech when.google.met.wikileaks.org Nobody wants to acknowledge that Google has grown big and bad. But it has. Schmidt’s tenure as CEO saw Google integrate with the shadiest of US power structures as it expanded into a geographically invasive megacorporation... Google is watching you when.google.met.wikileaks.org As Google enlarges its industrial surveillance cone to cover the majority of the world’s / WikiLeaks population... Google was accepting NSA money to the tune of... WHEN GOOGLE MET WIKILEAKS GOOGLE WHEN When Google Met WikiLeaks Google spends more on Washington lobbying than leading military contractors when.google.met.wikileaks.org WikiLeaks Search I’m Feeling Evil Google entered the lobbying rankings above military aerospace giant Lockheed Martin, with a total of $18.2 million spent in 2012. Boeing and Northrop Grumman also came below the tech… Transcript of secret meeting between Julian Assange and Google’s Eric Schmidt... wikileaks.org/Transcript-Meeting-Assange-Schmidt.html Assange: We wouldn’t mind a leak from Google, which would be, I think, probably all the Patriot Act requests... Schmidt: Which would be [whispers] illegal... Assange: Tell your general counsel to argue... Eric Schmidt and the State Department-Google nexus when.google.met.wikileaks.org It was at this point that I realized that Eric Schmidt might not have been an emissary of Google alone... the delegation was one part Google, three parts US foreign-policy establishment... We called the State Department front desk and told them that Julian Assange wanted to have a conversation with Hillary Clinton... -

The Iranian Revolution, Past, Present and Future

The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Dr. Zayar Copyright © Iran Chamber Society The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Content: Chapter 1 - The Historical Background Chapter 2 - Notes on the History of Iran Chapter 3 - The Communist Party of Iran Chapter 4 - The February Revolution of 1979 Chapter 5 - The Basis of Islamic Fundamentalism Chapter 6 - The Economics of Counter-revolution Chapter 7 - Iranian Perspectives Copyright © Iran Chamber Society 2 The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Chapter 1 The Historical Background Iran is one of the world’s oldest countries. Its history dates back almost 5000 years. It is situated at a strategic juncture in the Middle East region of South West Asia. Evidence of man’s presence as far back as the Lower Palaeolithic period on the Iranian plateau has been found in the Kerman Shah Valley. And time and again in the course of this long history, Iran has found itself invaded and occupied by foreign powers. Some reference to Iranian history is therefore indispensable for a proper understanding of its subsequent development. The first major civilisation in what is now Iran was that of the Elamites, who might have settled in South Western Iran as early as 3000 B.C. In 1500 B.C. Aryan tribes began migrating to Iran from the Volga River north of the Caspian Sea and from Central Asia. Eventually two major tribes of Aryans, the Persian and Medes, settled in Iran. One group settled in the North West and founded the kingdom of Media. The other group lived in South Iran in an area that the Greeks later called Persis—from which the name Persia is derived. -

A. Introduction the United Nations Population Fund-UNFPA

A. Introduction The United Nations Population Fund-UNFPA is an international development agency that works on population and development, sexual and reproductive health, and gender. In the area of ageing populations, UNFPA supports public policy and promotes policy dialogue to respond to the challenges posed by the social, health, and economic consequences of ageing populations – and to meet the needs of older persons, with particular emphasis on the poor, especially women. The Academy1 was created to promote practical approaches to human rights and humanitarian law as well as to strengthen links between human rights organizations, practitioners, and educators worldwide. The Academy’s programs, partnerships, research and scholarly endeavors were designed and implemented to enhance the culture and prominence of human rights and humanitarian law around the world. The initiatives have included, inter alia, empowering training for scholars, practitioners, and students interested in the international human rights systems and laws, in particular via the Program of Advanced Studies on Human Rights and Humanitarian Law. The Academy developed a number of research and scholarly projects to address the human rights concerns and challenges of vulnerable groups and the victims of human rights violations. The objective of this joint contribution is to provide input for the report by the UN Secretary General on the implementation of Resolution 65/182 on the situation of the rights of older persons in all regions. The content of the contribution provides for summarized findings on legislation, policies and programmes issued by states to protect, promote and fulfil the rights of older persons at national levels in five regions: Africa, Asia and the Pacific, Arab countries, Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean. -

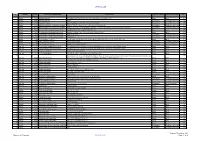

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan