Oojec FRBM S ) 0285 and AWDLIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

Les Projets D'assainissement Inscrit S Au Plan De Développement

1 Les Projets d’assainissement inscrit au plan de développement (2016-2020) Arrêtés au 31 octobre 2020 1-LES PRINCIPAUX PROJETS EN CONTINUATION 1-1 Projet d'assainissement des petites et moyennes villes (6 villes : Mornaguia, Sers, Makther, Jerissa, Bouarada et Meknassy) : • Assainissement de la ville de Sers : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés (mise en eau le 12/08/2016); * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Bouarada : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : les travaux sont achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Meknassy * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. • Makther: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2018. * Travaux complémentaires des réseaux d’assainissement : travaux en cours 85% • Jerissa: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 12/09/2014 ; * Réseaux d’assainissement : travaux achevés (Réception provisoire le 25/09/2017). • Mornaguia : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés Composantes du Reliquat : * Assainissement de la ville de Borj elamri : • Tranche 1 : marché résilié, un nouvel appel d’offres a été lancé, travaux en cours de démarrage. 1 • Tranche2 : les travaux de pose de conduites sont achevés, reste le génie civil de la SP Taoufik et quelques boites de branchement (problème foncier). * Acquisition de 4 centrifugeuses : Fourniture livrée et réceptionnée en date du 19/10/2018 ; * Matériel d’exploitation: Matériel livré et réceptionné ; * Renforcement et réhabilitation du réseau dans la ville de Meknassy : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 11/02/2019. -

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Quelques Aspects Problematiques Dans La Transcription Des Toponymes Tunisiens

QUELQUES ASPECTS PROBLEMATIQUES DANS LA TRANSCRIPTION DES TOPONYMES TUNISIENS Mohsen DHIEB Professeur de géographie (cartographie) Laboratoire SYFACTE FLSH de Sfax TUNISIE [email protected] Introduction Quelle que soit le pays ou la langue d’usage, la transcription toponymique des noms de lieux géographiques sur un atlas ou un autre document cartographique en particulier ou tout autre document d’une façon générale pose problème notamment dans des pays où il n’y a pas de tradition ou de « politique » toponymique. Il en est de même pour les contrées « ouvertes » à l’extérieur et par conséquent ayant subi ou subissant encore les influences linguistiques étrangères ou alors dans des régions caractérisées par la complexité de leur situation linguistique. C’est particulièrement le cas de la Tunisie, pays méditerranéen bien « ancré » dans l’histoire, mais aussi bien ouvert à l’étranger et subissant les soubresauts de la mondialisation, et manquant par ailleurs cruellement de politique toponymique. Tout ceci malgré l’intérêt que certains acteurs aux profils différents y prêtent depuis peu, intérêt matérialisé, entre autres manifestations scientifiques, par l’organisation de deux rencontres scientifiques par la Commission du GENUING en 2005 et d’une autre août 2008 à Tunis, lors du 35ème Congrès de l’UGI. Aussi, il s’agit dans le cadre de cette présentation générale de la situation de la transcription toponymique en Tunisie, dans un premier temps, de dresser l’état des lieux, de mettre en valeur les principales difficultés rencontrées en manipulant les noms géographiques dans leurs différentes transcriptions dans un second temps. En troisième lieu, il s’agit de proposer à l’officialisation, une liste-type de toponymes (exonymes et endonymes) que l’on est en droit d’avoir par exemple sur une carte générale de Tunisie à moyenne échelle. -

Directory of Higher Education Institutions (Higher Education and Research) Vv

Ministry of Higher Education www.universites.tn Directory of Higher Education Institutions (Higher Education and Research) Updated : July 2006 vv Document realized by « le Bureau de Communication Numérique » of the Ministry of Higher Education This document can be downloaded at this address : http://www.universites.tn/annuaire_ang.pdf Summary - Ez-zitouna University ......................................... 1 - Tunis University ................................................ 2 - Tunis El Manar University .................................... 4 - University of 7-November at Carthage .................. 6 - La Manouba University ........................................ 9 - Jendouba University ........................................... 11 - Sousse University .............................................. 12 - Monastir University ............................................ 14 - Kairouan University ........................................... 16 - Sfax University ................................................. 17 - Gafsa University ................................................ 19 - Gabes University ............................................... 20 - Virtual University ............................................... 22 - Higher Institutes of Technological Studies ............. 23 - Higher Institutes of Teacher Training .................... 26 Ez-Zitouna University Address : 21, rue Sidi Abou El Kacem Jelizi - Place Maakel Ezzaïm - President : Salem Bouyahia Tunis - 1008 General Secretary : Abdelkarim Louati Phone : 71 575 937 / 71 575 -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

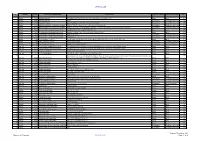

Entreprise Code Sec Ville Siege Adresse Tel Fax

ENTREPRISE CODE_SEC VILLE_SIEGE ADRESSE TEL FAX 1 BELDI IAA ARIANA Route de Mateur Km 8 71 521 000 71 520 577 2 BISCUITERIE AZAIZ IAA ARIANA 71 545 141 71 501 412 3 COOPERATIVE VITICOLE DE TUNIS IAA ARIANA Sabalet ben Ammar 71 537 120 71 535 318 4 GENERAL FOOD COMPANY IAA ARIANA Rue Metouia BORJ LOUZIR 71 691 036 70 697 104 5 GRANDE FABRIQUE DE CONFISERIE ORIENTALE - GFCO IAA ARIANA 11, Rue des Entrepreneurs Z.I Ariana Aroport 2035 Tunis-Carthage 70837411 70837833 6 HUILERIE BEN AMMAR IAA ARIANA Cebelet Ben Ammar Route de Bizerte Km 15 71 537 324 71 785 916 7 SIROCCO IAA ARIANA Djebel Ammar 71 552 365 71 552 098 8 SOCIETE AMANI IAA ARIANA Route Raoued Km 5 71 705 434 71 707 430 9 SOCIETE BGH IAA ARIANA Z.I Elalia Ben Gaied Hassine 71 321 718/70823945 70823944 10 SOCIETE CARTHAGE AGRO-ALIMENTAIRE IAA ARIANA Bourj Touil 70684001 70684002 11 SOCIETE DE SERVICES AGRICOLES ZAHRA IAA ARIANA Bouhnech - KALAAT EL ANDALUS 25 100 200 12 SOCIETE FROMAGERIE SCANDI IAA ARIANA 23 346 143/706800 70 680 009 13 SOCIETE FRUIT CENTER IAA ARIANA 35 Rue Mokhtar ATTIA 71 334 710 71 857 260 14 SOCIETE GIGA IAA ARIANA 70 308 441 71 308 476 15 SOCIETE GREEN LAND ET CIE IAA ARIANA route el battane jedaida 1124 mannoba 71798987 71784116 16 SOCIETE JASMIN EXPORT IAA ARIANA Rue Mohamed El Habib Route de Raoued Km 7 71 866 817 71 866 826 17 SOCIETE KACEM DE PATISSERIE - KAPCO IAA ARIANA 20 Rue Kalaat Ayoub Riadh El Andalous 71 821 388 71 821 466 18 SOCIETE LABIDI VIANDES IAA ARIANA Borj Touil 71 768 731 71 769 080 19 SOCIETE LE TORREFACTEUR IAA ARIANA Rue de l'argent -

Analysis of the Tunisian Tax Incentives Regime

Analysis of the Tunisian Tax Incentives Regime March 2013 OECD Paris, France Analysis of the Tunisian Tax Incentives Regime OECD mission, 5-9 November 2012 “…We are working with Tunisia, who joined the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters in July 2012, to review its tax incentives regime and to support its efforts to develop a new investment law.” Remarks by Angel Gurría, OECD Secretary-General, delivered at the Deauville Partnership Meeting of the Finance Ministers in Tokyo, 12 October 2012 1. Executive Summary This analysis of the Tunisian tax incentives regime was conducted by the OECD Tax and Development Programme1 at the request of the Tunisian Ministry of Finance. Following discussions with the government, the OECD agreed to conduct a review of the Tunisian tax incentive system within the framework of the Principles to Enhance the Transparency and Governance of Tax Incentives for Investment in Developing Countries.2 As requested by the Tunisian authorities, the objective of this review was to understand the current system’s bottlenecks and to propose changes to improve efficiency of the system in terms of its ability to mobilise revenue on the one hand and to attract the right kind of investment on the other. The key findings are based on five days of intensive consultations and analysis. Key Findings and Recommendations A comprehensive tax reform effort, including tax policy and tax administration, is critical in the near term to mobilize domestic resources more effectively. The tax reform programme should include, but not be limited to, the development of a new Investment Incentives Code, aimed at transforming the incentives scheme. -

The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, Vol

The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.nuhmafricanus3 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 Alternative title The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained Author/Creator Leo Africanus Contributor Pory, John (tr.), Brown, Robert (ed.) Date 1896 Resource type Books Language English, Italian Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast;Middle Niger, Mali, Timbucktu, Southern Swahili Coast Source Northwestern University Libraries, G161 .H2 Description Written by al-Hassan ibn-Mohammed al-Wezaz al-Fasi, a Muslim, baptised as Giovanni Leone, but better known as Leo Africanus. -

Rapport-Nord Ouest

Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement de la Région Economique du Nord-Ouest REPUBLIQUE TUNISIENNE MINISTERE DE L’EQUIPEMENT DE L’HABITAT ET DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE Direction Générale de l’Aménagement du Territoire SCHEMA DIRECTEUR D’AMENAGEMENT DE LA REGION ECONOMIQUE DU NORD-OUEST Juillet 2010 URAM 2010 0 Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement de la Région Economique du Nord-Ouest SCHEMA DIRECTEUR D’AMENAGEMENT DE LA REGION ECONOMIQUE DU NORD-OUEST Rapport final SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 PARTIE 1 : BILAN ET DIAGNOSTIC TERRITORIAL................................................................................................................................................ 5 I- BILAN REGIONAL .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1- LE MILIEU PHYSIQUE ET LES RESSOURCES NATURELLES........................................................................................................................... 8 1.1- ORIGINALITES ET SUBDIVISIONS CLIMATIQUES......................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2- ENSEMBLES OROGRAPHIQUES, HYDROGRAPHIQUES ET STRUCTURAUX ........................................................................................... -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment