Troy from Homer's Iliad to Hollywood Epic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Directors Guild Film Society and American Cinematheque Salute Production Designer Rolf Zehetbauer with “Das Boot” (1981) Screening / Panel

Art Directors Guild Film Society and American Cinematheque Salute Production Designer Rolf Zehetbauer With “Das Boot” (1981) Screening / Panel August 21, 5:30 p.m. Egyptian Theatre LOS ANGELES, August 8th, 2011 — The Art Directors Guild (ADG) Film Society and American Cinematheque will spotlight Das Boot AKA The Boat (1981) with a special 30th anniversary screening of the remastered director’s cut on Sunday, August 21 at 5:30 p.m. at the Egyptian Theatre (6712 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood). The film, designed by Award winning Production Designer Rolf Zehetbauer (Cabaret, The NeverEnding Story ) is the fourth in this year’s series highlighting the work of renowned Production Designers and their creative colleagues. A discussion will follow, enlightening the audience about the unique challenges of filming Das Boot, a wartime action film, nearly all of which takes place inside the claustrophobic interior of a German U-Boat, or WW2 submarine. Production Designer John Muto will host a panel that will include an expert on submarine warfare provided by the U.S. Navy. For information: http://www.americancinemathequecalendar.com/content/das-boot-0 Possibly one of the best-known German films of all time, Das Boot (1981), directed by Wolfgang Petersen, is based on the novel by Lothar Günther Buccheim and carries a strong anti-war message, drawn from the experiences of Second World War veterans in one of Germany’s infamous U-boat submarines. Nominated for six Oscars, the film stars Jürgen Prochnow, Herbert Grönemeyer and Klaus Wennermann in the fictional story of a U-96 and its crew patrolling the waters during World War II. -

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Ransom Is a Story of Vengeance Clashing with Grief.’ Discuss

‘Ransom is a story of vengeance clashing with grief.’ Discuss. In his lyrical novel, Ransom, David Malouf reimagines the final book of The Iliad, and in doing so, highlights the futility of countering grief with vengeance. He asserts the pointlessness of such vengeful actions, examines the role of the ‘rough world of men’ in creating it, and notes its cyclic nature, leaving many readers disheartened. However, Malouf also demonstrates how grief can be overcome with honourable actions. Malouf demonstrates to readers the uselessness of trying to assuage grief with acts of revenge. He introduces this concept right from the outset of the novel through his characterisation of Achilles. Malouf moves away from the traditional portrayal of Achilles as the most formidable of the Greeks and instead describes him as hollow and like a dead man. This new perspective of Achilles depicts him as lacking balance and feeling trapped in a clogging grey web due to his grief over the death of his soulmate Patroclus. Once Malouf describes Achilles’ barbaric actions in dragging around the corpse of Patroclus’ killer, Hector, it becomes clear to readers that Achilles is attempting to assuage his grief with violence and brutal, callous actions. Malouf uses imagery to depict Achilles as already dead himself as he continues to desecrate Hector’s body, by describing him as caked with dust like a man who has walked out of his grave. Thus, Malouf asserts how Achilles’ act of revenge has only wasted his spirit and left him feeling that it was never enough; being unable to overcome his pain at the loss of his friend. -

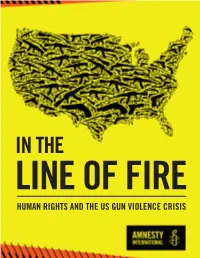

In the Line of Fire 1

1 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL: IN THE LINE OF FIRE AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL: TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................8 Key recommendations .................................................................................................................................................18 Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................................20 Glossary of abbreviations and a note on terminology .....................................................................................................21 Methodology ...............................................................................................................................................................23 Chapter 1: Firearm Violence: A Human Rights Framework ............................................................................................24 1.1 The right to life .................................................................................................................................... 25 1.2 The right to security of person ................................................................................................................ 25 1.3 The rights to life and to security of person and firearm violence by private actors and in the community ........ 26 1.4 A system of regulation based on international guidelines -

Homer's Iliad Via the Movie Troy (2004)

23 November 2017 Homer’s Iliad via the Movie Troy (2004) PROFESSOR EDITH HALL One of the most successful movies of 2004 was Troy, directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Brad Pitt as Achilles. Troy made more than $497 million worldwide and was the 8th- highest-grossing film of 2004. The rolling credits proudly claim that the movie is inspired by the ancient Greek Homeric epic, the Iliad. This was, for classical scholars, an exciting claim. There have been blockbuster movies telling the story of Troy before, notably the 1956 glamorous blockbuster Helen of Troy starring Rossana Podestà, and a television two-episode miniseries which came out in 2003, directed by John Kent Harrison. But there has never been a feature film announcing such a close relationship to the Iliad, the greatest classical heroic action epic. The movie eagerly anticipated by those of us who teach Homer for a living because Petersen is a respected director. He has made some serious and important films. These range from Die Konsequenz (The Consequence), a radical story of homosexual love (1977), to In the Line of Fire (1993) and Air Force One (1997), political thrillers starring Clint Eastwood and Harrison Ford respectively. The Perfect Storm (2000) showed that cataclysmic natural disaster and special effects spectacle were also part of Petersen’s repertoire. His most celebrated film has probably been Das Boot (The Boat) of 1981, the story of the crew of a German U- boat during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941. The finely judged and politically impartial portrayal of ordinary men, caught up in the terror and tedium of war, suggested that Petersen, if anyone, might be able to do some justice to the Homeric depiction of the Trojan War in the Iliad. -

Pdf, 445.80 KB

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Music “War” off the album War & Peace by Edwin Starr. Impassioned, intense funk. War! Huh! Yeah! [Song fades down and plays quietly as the hosts speak.] 00:00:02 Adam Host Hey, here’s some breaking news about Friendly Fire! We’ve Pranica launched an official Friendly Fire online store! So head over to Store.FriendlyFire.fm. It’s stocked with three brand-new items. We’ve got a Friendly Fire logo shirt—available in three colors on a nice, soft T-shirt fabric; we have a thick, diner-style, 120-sided die logo coffee mug; and finally we have a limited-edition challenge coin. It’s our very first Friendly Fire challenge coin. And we’re only gonna make 250 of these. And all three of these items are now in the brand-new Friendly Fire online store! So head over to Store.FriendlyFire.fm and here’s the thing—orders have to be placed on or before December 11th to make sure that those items arrive before December 25th. So you have about a week to get into the store and get these brand-new Friendly Fire items. We hope you do. That’s Store.FriendlyFire.fm. [Music stops.] 00:01:01 Rob Schulte Producer A warning before this episode: today’s film depicts a sexual assault, which is discussed in the review. -

NCHJA Annual Horse Show

NCHJA ANNUAL HORSE SHOW June 30 - July 4, 2021 HUNTER / JUMPER / EQUITATION USEF AA PREMIER RATED SHOW Featuring: $30,000 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE/USHJA GREEN HUNTER INCENTIVE SOUTH CHAMPIONshIps ($15,000 PER SECTION) PLEASE JOIN US FOR RINGSIDE HOSPITALITY WHILE WATCHING THIS SPECTACULAR CLASS. HUNT HORSE COMPLEX, RALEIGH, NC • www.nchja.com ANNUAL HORSE SHOW HUNTER JUMPER EUITATION U S E F A A - R AT E D Welcome! Hunt Horse Complex Raleigh, NC Dear Members, Friends, Exhibitors and Supporters, It is with much excitement and pleasure that the North Carolina Hunter Jumper Association Board of Directors and Annual Horse Show Committee welcomes you back to Raleigh for the 39th NCHJA Annual Horse Show! The Annual Show is always proud to celebrate our membership and never more so than now. As we are finally experiencing some semblance of a return to a “careful normal” we hope the horse show can be a shared experience of happiness and joy with the animals and sport we all love and cherish. This horse show has seen many changes over its 39 years… changes of venue, changes in the schedule, the divisions, the staff but hopefully the feeling of hospitality has remained and our members, competitors, families and friends will look forward to another year of gathering together and celebrating each others accomplishments this summer. This year’s schedule is much the same with our Equitation Finals on Friday and Saturday evenings, the Platinum Performance / USHJA Green Hunter Incentive South Championships on Friday, and the National Derby and Pony Derbies being feature events. We hope you will take time to enjoy our daily hospitality as well as the excellent food trucks and ringside events that are planned as you enjoy seeing old friends and making new ones. -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

Breaking the Silence of Homer's Women in Pat Barker's the Silence

International Journal of English Language Studies (IJELS) ISSN: 2707-7578 DOI: 10.32996/ijels Website: https://al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/ijels Breaking the Silence of Homer’s Women in Pat Barker’s the Silence of The Girls Indrani A. Borgohain Ph.D. Candidate, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan Corresponding Author: Indrani A. Borgohain, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: December 25, 2020 Since time immemorial, women have been silenced by patriarchal societies in most, if Accepted: February 10, 2021 not all, cultures. Women voices are ignored, belittled, mocked, interrupted or shouted Volume: 3 down. The aim of this study examines how the contemporary writer Pat Barker breaks Issue: 2 the silence of Homer’s women in her novel The Silence of The Girl (2018). A semantic DOI: 10.32996/ijels.2021.3.2.2 interplay will be conducted with the themes in an attempt to show how Pat Barker’s novel fit into the Greek context of the Trojan War. The Trojan War begins with the KEYWORDS conflict between the kingdoms of Troy and Mycenaean Greece. Homer’s The Iliad, a popular story in the mythological of ancient Greece, gives us the story from the The Iliad, Intertextuality, perspective of the Greeks, whereas Pat Barker’s new novel gives us the story from the Adaptation, palimpsestic, Trojan perspective of the queen- turned slave Briseis. Pat Barker’s, The Silence of the Girls, War, patriarchy, feminism written in 2018, readdresses The Iliad to uncover the unvoiced tale of Achilles’ captive, who is none other than Briseis. In the Greek saga, Briseis is the wife of King Mynes of Lyrnessus, an ally of Troy. -

HYADES Star and Rain Nymphs | Greek Mythology

Google Search HYADES Web Theoi Greek Name Transliteration Latin Name Translation Ὑας Hyas Sucula Rainy Ones Ὑαδες Hyades Suculae (hyô, hyetos) THE HYADES were the nymphs of the five stars of the constellation Hyades. They were daughters of the Titan Atlas who bore the starry dome of heaven upon his shoulders. After their brother Hyas was killed by a lion, the tear-soaked sisters were placed amongst the stars as the constellation Hyades. Hyas himself was transformed into the constellation Aquarius. The heliacal setting of their constellation in November marked the start of the rainy season in Greece, hence the star nymphs were known as "the Rainy Ones." According to Nonnus the Hyades were the same as the Lamides nurses of the god Dionysos. The Hyades were also closely identified with the Nysiades and Nymphai Naxiai, the other reputed nurses of the god. The Hyades were also connected with the Naiades Mysiai, in which their brother Hyas is apparently substituted for a lover, Hylas. PARENTS [1.1] ATLAS & PLEIONE (Hyginus Fabulae 192) [1.2] ATLAS & AITHRA (Musaeus Frag, Hyginus Astronomica 2.21, Ovid Fasti 5.164) [2.1] HYAS & BOIOTIA (Hyginus Astronomica 2.21) NAMES [1.1] PHAISYLE, KORONIS, KLEEIA, PHAIO, EUDORE (Hesiod Astronomy 2) [1.2] PHAESYLA, KORONIS, AMBROSIA, POLYXO, EUDORA (Hyginus Fabulae 192) [1.3] AMBROSIA, EUDORA, AESYLE (Eustathius on Homer's Iliad 1156) ENCYCLOPEDIA HY′ADES (Huades), that is, the rainy, the name of a class of nymphs, whose number, names, and descent, are described in various ways by the ancients. Their parents were Atlas and Aethra ( Ov. -

Helen of Troy

T H E P O E T I C A L WO R K S A N D R E W L A N G I V OL . V TH E P O E T I CAL Wo rm s * W L A 3 ! d i b N E ted y M rs. L A G I N F 0UR VOLUM ES . VOL V . I With Port r ai n m (J r ee o L o g a l s n 63 L . P a te rn oste r R ow n E C . 39 , Lo don , . 4, N ew Y o rk Tor n to , o Bo m ba Ca c u t ta a nd M a a s y , l , d r $3“ k; on( 9 e! TH E PO ET I C AL WO R K S dited N G E by M r s . LA I N F OUR V OLUM ES V O L . I V 8 Ll O 3 \V ith P or tr a i ’ a tc rn ost r R w do n e o Lo n E C . , , . N ew Y r k T r n t o , o o o B m ba C a c u a a n d M a a s o y , l t t , d r fi %L eff M a d e i n! G r ea t TA BLE OF CON TE N TS V OLUM E I V XV H EL EN OF TR OY D edic a t io n : To a ll Old F ri e nd s The Com i ng ofP a ris Th e S p e ll ofAp h rodite Th e F light ofH e l e n Th e D e a th ofCo ry t h u s Th e \V a r Th e S a c k o fT ro T h e R u n o fH n y . -

Blutvergiessen Geht Weiter Chen Schweiz Die Schweizerinnen Und Schwei - Zer Sind Ein fleissiges Volk

AZ 3900 Brig | Diens tag, 8. März 2011 Nr. 56 | 171. Jahr gang | Fr. 2.20 www.1815.ch | Re dak ti on Te le fon 027 922 99 88 | Abon nen ten dienst Te le fon 027 948 30 50 | Men gis Mediaverkauf Te le fon 027 948 30 40 | Auf la ge 24 677 Expl. INHALT Wallis Wallis Sport wallis 2 – 13 traueranzeigen 12 Sport 15 – 19 Wildhut Überzeugend Der Jüngste Ausland 21/23 Der Jagd-Chef Peter Der Schriftsteller Rolf Her - GCk-Leihgabe Sven Andrig - Schweiz 22/23 Hintergrund 24 Scheibler will die Zahl der mann versteht es, mit seinen hetto, noch keine 18, spielt wirtschaft/börse 25 walliser wildhüter nicht Gedichten das Publikum zu mit Visp bereits beachtliche tV-Programme 26 wohin man geht 27 reduzieren. | Seite 2 fesseln. | Seite 5 Playoffs. | Seite 15 wetter 28 Tripolis | EU und UNO schicken Krisenteams KOMMENTAR Arm in der rei - Blutvergiessen geht weiter chen Schweiz Die Schweizerinnen und Schwei - zer sind ein fleissiges Volk. Im Ge - Gaddafi-treue Truppen setzen ihre schäftsbericht des Bundesrates Offensive gegen die libyschen Auf - ständischen fort. Sie nahmen die für das abgelaufene Jahr steht es strategisch wichtige Ölstadt Ras schwarz auf weiss: Im internatio - Lanuf ins Visier. International wer - nalen Vergleich weist unser Land den die Rufe nach einer Militärin - mit 85,5 % der 25- bis 64-Jähri - tervention in Libyen lauter. gen eine der höchsten Erwerbs - quoten überhaupt auf. Nirgends Um weitere Bombenangriffe auf die liby - in Europa ist die Erwerbsquote sche Bevölkerung zu verhindern, arbeiten bei Männern höher als bei uns – Frankreich und Grossbritannien nach An - satte 93 %.