Paris, Not France and the Dialogic World of the Celebrity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Working Draft Raw Materials, Creative Works, and Cultural

Early Working Draft Raw Materials, Creative Works, and Cultural Hierarchies Andrew Gilden In disputes involving creative works, courts increasingly ask whether a preexisting text, image or persona has been used as “raw material” for new authorship. If so, the accused infringer becomes shielded by the fair use doctrine under copyright law or a First Amendment defense under right of publicity law. Although copyright and right of publicity decisions have begun to rely heavily on the concept, neither the case law nor existing scholarship has explored what it actually means to use something as “raw material,” whether this inquiry adequately draws lines between infringing and non- infringing conduct, or how well it maps onto the expressive values that the fair use doctrine and the First Amendment defense aim to capture This Article reveals serious problems with the raw material inquiry. First, a survey of all decisions invoking raw materials uncovers troubling distributional patterns; in nearly every case the winner is the party in the more privileged class, race or gender position. Notwithstanding courts’ assurance that the inquiry is “straightforward,” distinctions between raw and “cooked” materials appear to be structured by a range of social hierarchies operating in the background. Second, these cases express ethically troubling messages about the use and reuse of text, image and likeness. The more offensive, callous and objectionable the appropriation, the more visibly “raw” the preexisting material is likely to be. Given the shortcomings of the raw material inquiry, this Article argues that courts should engage more directly with an accused infringer’s actual creative process and rely less on a formal comparison between the two works in dispute. -

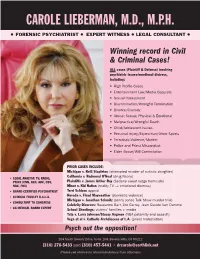

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. l FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST l EXPERT WITNESS l LEGAL CONSULTANT l Winning record in Civil & Criminal Cases! ALL cases (Plaintiff & Defense) involving psychiatric issues/emotional distress, including: • High Profile Cases • Entertainment Law/Media Copycats • Sexual Harassment • Discrimination/Wrongful Termination • Divorce/Custody • Abuse: Sexual, Physical & Emotional • Malpractice/Wrongful Death • Child/Adolescent issues • Personal Injury/Equestrian/Other Sports • Terrorism/Violence/Murder • Police and Priest Misconduct • Elder Abuse/Will Contestation PRIOR CASES INCLUDE: Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted murder of autistic daughter) California v. Redmond O’Neal • LEGAL ANALYST: TV, RADIO, (drug felony) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray PRINT (CNN, HLN, ABC, CBS, (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) NBC, FOX) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV → emotional distress) Terri Schiavo • BOARD CERTIFIED PSYCHIATRIST appeal Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather • CLINICAL FACULTY U.C.L.A. (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz • CONSULTANT TO CONGRESS (Jenny Jones Talk Show murder trial) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme • CA MEDICAL BOARD EXPERT School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Vega et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Psych out the opposition! 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108, Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 457-5441 [email protected] and • (Please see reverse for recommendations from attorneys) Here’s what your colleagues are saying about Carole Lieberman, M.D. Psychiatrist and Expert Witness: “I have had the opportunity to work with the “I have rarely had the good fortune to present best expert witnesses in the business, and I such well-considered testimony from such a would put Dr. -

Fame Us Introduction

FAME US INTRODUCTION Brian Howell A while ago, I started taking pictures of celebrity impersonators after a string of chance encounters with look-alikes. When I began researching the subject, I had no idea that so many people made a living at it. I became intrigued, and as a result, this project was born. I attended a number of conventions for the celebrity imper- sonator industry; there are two major gatherings a year: Las Vegas in the spring and Orlando, Florida in the fall. The impersonators are there to showcase their tal- ent and to network with others in the industry; the conventions are like any other, except that on any given day, you might see George W. Bush hamming it up with Ozzy Osbourne, or bump into Marilyn Monroe wearing her dress from The Seven Year Itch, except there is no subway air vent to blow it up to her waist. Impersonation is a full-time career for many of the people who appear in this book. Some of them make a great living at it, including a few who look more like the ce- lebrity they impersonate than the actual celebrity himself. While getting to know them better, I’ve learned that the biggest misconception about impersonators is that they are somehow obsessed fans desperate to physically become the celebrity they impersonate. But I never met anyone like that. On the contrary, many imper- sonators got into the business because of others—those passersby on the street who stop and stare, and ask, “Has anyone ever told you you look like…?” Simply put, and not in a derogatory way, impersonators are opportunistic, taking advan- tage of a culture with an insatiable, uncontrollable thirst for celebrity and all that it entails. -

FESTIVAL to the Volcanoes of Auvergne – Unforgettable

InsPIrIng you to reach your dreams #19 /JuLy-AUGUST 2010 Glorious Cannes, Glamorous summer MICK JAGGER A Stone in exile? PAlme d’oR wInner Exclusive interview AlEx Cox British film expert BElGIAn EU PRESIdEnCY Back in business? EDITORIAL Cannes-tastic! Cannes is one of those places cocktails, courtesy of chivas and the utter where you feel anything could exhilaration of being handed the controls of J happen. Away from the glitz craft’s latest speedboat the Torpedo as it and glamour of La Croisette topped 40 knots in Cannes harbour, we did our best to enjoy ourselves. and its famous red carpet, a whole industry throbs in the Of course, it’s not all parties. Closer to home, Andy background. Carling returns with a sideways look at how Belgium may handle its six months as head of n such a city of movers and shakers, a the EU’s rotating presidency. There’s still time to place which seems practically never to get yourself in trim for the beach, too – let Together sleep and a town in which new stars are and Power Plate Institute Brussels introduce you born, Together is right at home. To save to the latest exercise craze, with our fantastic you the trouble of trekking the thousand- readers giveaway. oddI kilometres to Cannes, we selflessly ventured there to bring you the very best in fashion shows, Plus, as we know you’ve come to expect and private parties and everything you might expect enjoy by now, there’s a beautiful fashion from the hardest working (and hardest partying) photoshoot, Kimberley Lovato’s sensual magazine in Brussels. -

Celebrity Rankings Study

Interview dates: December 19-21, 2006 Interviews: 1,004 adults, 779 registered voters Margin of error: +3.1 for all adults; +3.6 for registered voters Project #81-5861-25 Associated Press/AOL Celebrity Rankings Study Celebrity Rankings Study 1. If you were asked to name a famous person to be the biggest villain of the year, whom would you choose? George W. Bush 25% Osama bin Laden 8% Saddam Hussein 6% President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran 5% Kim Jong Il, North Korean leader 2% Donald Rumsfeld 2% John Kerry 1% Rosie O'Donnell 1% Dick Cheney 1% Hillary Clinton 1% Brad Pitt 1% Tom Cruise 1% Satan/The Devil 1% Donald Trump 1% O.J. Simpson 1% Hugo Chavez 1% George Clooney 1% Nancy Pelosi 1% Bill Clinton 1% Colin Farrell 1% Oprah Winfrey 1% Mel Gibson - Paris Hilton - Terrell Owens - Britney Spears - Angelina Jolie - Arnold Schwarzenegger - Santa Claus - Bill O'Reilly - Martha Stewart - Matt Damon - Other 15% None - (DK/NS) 20% 1101 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 www.Ipsos-NA.com/PA (202) 463-7300 Ipsos Public Affairs Project #81-5861-25 Page 2 December 19-21, 2006 AP-AOL Celebrity Rankings Study 2. If you were asked to name a famous person to be the biggest hero of the year, whom would you choose? George W. Bush 13% Soldiers/troops in Iraq 6% Oprah Winfrey 3% Barack Obama 3% Jesus Christ 3% Bono 2% Angelina Jolie 1% Al Gore 1% Arnold Schwarzenegger 1% Colin Powell 1% Mel Gibson 1% George Clooney 1% Bill Gates 1% Donald Rumsfeld 1% Bill Clinton 1% Jimmy Carter 1% Martin Luther King 1% Condoleeza Rice 1% Billy Graham 1% Warren Buffett 1% Pope Benedict - Hillary Clinton - Brad Pitt - Paris Hilton - Nancy Pelosi - Tiger Woods - John McCain - Sylvester Stallone - Tom Cruise - Lance Armstrong - Donald Trump - Mother Theresa - Ladainian Tomlinson - Brett Favre - Other 25% None 1% (DK/NS) 27% Ipsos Public Affairs Project #81-5861-25 Page 3 December 19-21, 2006 AP-AOL Celebrity Rankings Study 3. -

Literatura Y Otras Artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and His Multiple Identities »

TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO « Literatura y otras artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and his multiple identities » Autor: Juan Muñoz De Palacio Tutor: Rafael Vélez Núñez GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Curso Académico 2014-2015 Fecha de presentación 9/09/2015 FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD DE CÁDIZ INDEX INDEX ................................................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARIES AND KEY WORDS ........................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 1. HIP HOP ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. THE 4 ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 8 1.2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................. 10 1.3. WORLDWIDE RAP ............................................................................................................. 21 2. EMINEM ................................................................................................................. 25 2.1. BIOGRAPHICAL KEY FEATURES ............................................................................................. 25 2.2 RACE AND GENDER CONFLICTS ........................................................................................... -

Party of the Year

SOCIAL SAFARI | by R. COURI HAY Ariana Madonna @ Rockefeller, Raising Malawi Hannah Selleck and Georgina Bloomberg @ NY Botanical Garden Winter Wonderland Ball Event planner Harriette Rose Katz @ Animal Ashram Anne Hathaway @ NY Botanical Prince Pavlos, Garden Princess Marie- Winter Chantal and Wonderland Princess Olym- Bal pia of Greece and Denmark graced Gstaad Board Members Audrey and Martin Gruss @ Lincoln Center Fund Gala, Georgina Chapman honoring Carolina Herrera hosted a dinner in Gstaad PARTYGstaad,Valentino, Georgina OF Chapman, THE Botanical Garden, CarolinaYEAR Herrera, Karolína Wilbur Ross, Madonna & Animal Ashram Kurková @ Raising Malawi TEARS OF A CLOWN artwork by Damien Hirst, Ai Weiwei, Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sher- If parties could win an Oscar, then Madonna’s Raising Malawi baccha- man, Richard Prince, Steven Meisel and a piece by Tracey Emin, nal would take home top honors for 2016. It was a night of a hundred who beamed from the audience when it sold for $550,000. Karolína stars including Leonardo DiCaprio, Adriana Lima, A-Rod, Donna Kurková sold a diamond snake by Bulgari to Prince Alexander von Karan, Len Blavatnik, Jeremy Scott, Natasha Poly, Alexander Gilkes, Furstenberg for $180,000, but only afer she ofered to lick the serpent. P. Diddy, Calvin Klein, Ron Burkle and David Blaine, who smirked Ooh la la! When a Fiat 500 came on the block, she slapped Agnelli as he swallowed a broken wineglass. Tey all played a role in this night heir Lapo Elkann, saying, “Tis car has been arrested along with its of fun, performance -

Event Sponsorship Proposal

presents 8th Edition CONTENTS I. About Us p.3 The Company – VIP Belgium p.3 References p.4 The Foundation – Wheeling Around the World p.6 The Founder p.7 II. Cine-Arts Galas p.8 The Concept p.8 Cine-Arts Gala 2015 p.9 Cine-Arts Gala 2016 p.12 Gala Program p.13 Auction p.14 III. Become a Partner p.15 Sponsorship Opportunities p.15 Communication Benefits p.15 IV. Contact p.16 2 I. About Us The company VIP Belgium Founded in 2008, VIP BELGIUM has been a key player in the Belgian and international events scene. It organizes events including private parties, galas, company and charity events. Since the last eight years, VIP BELGIUM has also been renowned for its outstanding events held during the International Film Festival in Cannes at the most exclusive locations such as private Yachts and Villas, Majestic Hotel, Grand Hyatt Cannes Hotel Martinez, the Palm Beach,… Each time, a unique concept not only brings together the Belgian and the French, but also the international audience of the Cannes Film Festival. VIP BELGIUM is an active society, trusted within its field, with a solid reputation among its most loyal customers. www.vipbelgium.com From left to right: Michelle Rodriguez, Penelope Cruz, Bruce Willis, Jean-Claude Van Damme, VIP Belgium Yacht at Cannes Film Festival 2010, Prince Albert of Monaco 3 Reference A quick overview of companies which have already trusted Alexandre Bodart Pinto: 4 They talked about us: 5 The Foundation Wheeling Around the World Nowadays, 20% of the population faces disability, forming the largest minority in the world. -

Toreador of Paris: Facilitated Various Parties and Individual Pleasures

Toreador of Paris: Facilitated various parties and individual pleasures. The most public and lucrative of these was probably the unicorn viewing. Unicorn Viewing 600 euros [per ticket] Party on June 10th (with wine) 52,000 euros Party on June 12th (without wine) 20,000 euros Private Session on June 13th 500 euros Private Session on June 14th (All night) 31,000 euros Party on June 17th (with wine) 81,000 euros Unicorn Viewing (2) 800 euros [per ticket] Party on June 20th (without wine) 16,000 euros Private Session on June 22nd 41,000 euros Private Session on June 23rd (All night) 0 euros Public Beating on June 26th 1000 euros [per ticket] Party on June 27th (with wine) 65,000 euros Attendance: Unicorn Viewing: 42 Kindred (25,200 euros) Unicorn Viewing (2): 31 Kindred (24,800 euros) Public Beating: 15 Kindred (15,000 euros) Total: 311,500 euros 430,617 dollars Nosferatu of Germany – The Nosferatu were given free access to the illusion of Hedi Klum, a svelte German model, in exchange for information on Ash Gently, but those who wanted specific things still had to pay. Private Session on July18 (Toni Garrn) 50 euros Private Session on July18 (Daniela Amavia) 50 euros Private Session on July19 (Blond woman) 50 euros Private Session on July19 (Carlott Cordes) 50 euros Private Session on July19 (Mary Kate and Ashley) 150 euros Private Session on July20 (Toni Garrn) 50 euros Private Session on July20 (Daniela Amavia) 50 euros Private Session on July20 (Madonna) 50 euros Private Session on July21 (Madonna) 50 euros Private Session on July21 (Madonna) -

ACTIVITY 17: CELEBRITY SEARCHES in This Activity,You Will Practice How To: 1

New Reinforced: ACTIVITY 17: CELEBRITY SEARCHES In this activity,you will practice how to: 1. merge cells in a spreadsheet. 2. insert a page footer. Activity Overview: Most people are quite familiar with Internet search engines. Yahoo!®, one of the most popular search engines on the Web, allows users to find content within a specific criteria. Each year, Yahoo!® publishes the top searches its users made in many categories. Looking back at these lists can give anyone a sense of what was popular and in the news for the given year. Since the lists cover everything from celebrities and news to sports and entertainment, a fact seeker or trivia buff will never be without accurate data on what Internet users were looking for. The following activity illustrates how spreadsheets can be used to list the top celebrity internet searches made by Yahoo!® users. Instructions: 1. Create a NEW spreadsheet. Note: Unless otherwise stated, the font should be set to Arial, the font size to 10 point. 2. Type the data as shown. 3. Use AutoFill to complete the number sequence in column A. 4. Format the width of column A to 6.0 and center align. 5. Format the width of column B to 28.0 and left align. 6. Format the width of columns C and D to 14.0 and right align. NEW SKILL 7. Merge and center the text that is shown in cells B1 and B2 across columns B, C, and D. 8. Insert a header that shows: a. Left Section Activity 17-Student Name b. -

Neuroimaging Results Suggest the Role of Prediction in Cross-Domain Priming

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Neuroimaging results suggest the role of prediction in cross-domain priming Received: 3 April 2018 Catarina Amado1, Petra Kovács2, Rebecca Mayer2,3, Géza Gergely Ambrus 1, Sabrina Trapp4 Accepted: 25 June 2018 & Gyula Kovács1,2 Published: xx xx xxxx The repetition of a stimulus leads to shorter reaction times as well as to the reduction of neural activity. Previous encounters with closely related stimuli (primes) also lead to faster and often to more accurate processing of subsequent stimuli (targets). For instance, if the prime is a name, and the target is a face, the recognition of a persons’ face is facilitated by prior presentation of his/her name. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the prime allows predicting the occurrence of the target. To the best of our knowledge, so far, no study tested the neural correlates of such cross-domain priming with fMRI. To fll this gap, here we used names of famous persons as primes, and congruent or incongruent faces as targets. We found that congruent primes not only reduced RT, but also lowered the BOLD signal in bilateral fusiform (FFA) and occipital (OFA) face areas. This suggests that semantic information afects not only behavioral performance, but also neural responses in relatively early processing stages of the occipito-temporal cortex. We interpret our results in the framework of predictive coding theories. Te repeated presentation of a given stimulus leads to several behavioral and neural consequences. On the one hand, stimulus repetitions enhance performance, as indicated by shorter reaction times, an efect referred to as (immediate) repetition priming1,2. -

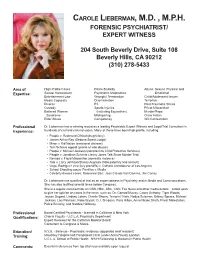

Carole Lieberman, Md , Mph Forensic Psychiatrist

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D. , M.P.H. FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST/ EXPERT WITNESS 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 Area of High Profile Cases P olice Brutality Abuse: Sexual, Physical and Expertise: Sexual Harassment Psychiatric Malpractice Emotional Entertainment Law Wrongful Termination Child/Adolescent Issues Media Copycats Discrimination Terrorism Divorce P.I. Post-Traumatic Stress Custody S ports Injuries Priest Misconduct B attered Woman (Including Equestrian) Murder/Rape Syndrome Malingering Class Action Elder Abuse Competency Will Contestation Professional Dr. Lieberman has a winning record as a leading Psychiatric Expert Witness and Legal/Trial Consultant in Experience: hundreds of civil and criminal cases. Many of these have been high profile, including: • P eople v. Redmond O'Neal (drug felony) • J ames Arthur Ray (Sedona Sweat Lodge) • Mino r v. Kid Nation (emotional distress) • T erri Schiavo appeal (profile of wife abuser) • P eople v. Michael Jackson (complaint to Child Protective Services) • P eople v. Jonathan Schmitz (Jenny Jones Talk Show Murder Trial) • Nevada v. Floyd Maywether (domestic violence) • T ate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) • V ega, Rodriguez et al (key plaintiffs) v. Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles • S chool Shooting cases: Families v. Media • Celebrity divorce cases: Roseanne Barr, Jean Claude Van Damme, Jim Carrey Dr. Lieberman has qualified at trial as an expert witness in Psychiatry and in Media and Communications. She has also testified several times before Congress. She is a regular commentator on CBS, NBC, ABC, CNN, Fox News and other media outlets – called upon to give her opinion on cases in the news, such as: Dr.