DOWNLOAD PAGE AND/OR PRINT for RESEARCH/REFERENCE Patrick H Gormley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/[14927] Clare Smith Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith University of Wales: Trinity St. David United Kingdom Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8 ISBN 978-1-137-59999-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59999-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938047 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author has/have asserted their right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accor- dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. -

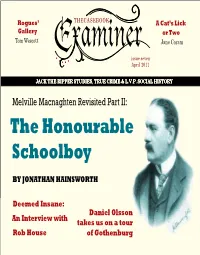

EXAMINER Issue 7.Pdf

THE CASEBOOK Rogues’ A Cat’s Lick Gallery or Two Tom Wescott Jane Coram issue seven April 2011 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY Melville Macnaghten Revisited Part II: The Honourable Schoolboy BY JONATHAN HAINSWORTH Deemed Insane: Daniel Olsson An Interview with takes us on a tour Rob House of Gothenburg THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 7 April 2011 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of signed issue seven articles, essays, letters, reviews and April 2011 other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, CONTENTS: transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including digital, electronic, printed, mechanical, Has it Really Been a Year? Pg 3 Photographs of Dr LionelDruitt photocopying, recording or any other, Adam Went Pg 69 without the express written permission Melville Macnaghten Revisited of Casebook.org. The unauthorized Jonathan Hainsworth Pg 5 Book Reviews Pg 73 reproduction or circulation of this publication or any part thereof, A Berner Street Rogues Gallery Open Book Exam whether for monetary gain or not, is DonSouden Pg 81 Tom Wescott Pg 30 strictly prohibited and may constitute copyright infringement as defined in Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour A Cat’s Lick or Two domestic laws and international agree- Gothenburg ments and give rise to civil liability and Jane Coram Pg52 Daniel Olsson Pg 87 criminal prosecution. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in What if It Was? Deemed Insane: An Interview with articles, essays, letters and other items Don Souden Pg 63 Rob House Pg 99 published in Casebook Examiner are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of Casebook. -

Tom Wescott Gets Decadent the CASEBOOK the Contents of Casebook Examiner No

THE CASEBOOK George The Man Who Hutchinson’s Wasn’t There “Turn on the Christer Holmgren defensive” issue five Benedict Holme December 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY EVOLVING THEORIES WILDE IDEAS &Corey Browning enters the jungle and Tom Wescott gets Decadent THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 5 December 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue five signed articles, essays, letters, reviews December 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may CONTENTS: be reproduced, stored in a retrieval It’s Christmas Time pg 3 On The Case system, transmitted or otherwise cir- culated in any form or by any means, Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 93 including digital, electronic, printed, On The Case Extra George Hutchinson’s mechanical, photocopying, recording or Feature Story pg 95 “Turn on the defensive” any other, without the express written Benedict Holme pg 6 On The Case Puzzling permission of Casebook.org. The unau- The Darker Side of Evolution Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 100 thorized reproduction or circulation of Corey Browning pg 20 On The Case Back Story this publication or any part thereof, Mary Kelly and the Decadents Feature Story pg 102 whether for monetary gain or not, is Tom Wescott pg 45 Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour strictly prohibited and may constitute copyright infringement as defined in The Man Who Wasn’t There Hull pg 103 Christer Holmgren pg 55 CSI: Whitechapel domestic laws and international agree- Graffito pg 110 ments and give rise to civil liability Undercover Investigations and criminal prosecution. -

Mary Ann Nicholls: “Polly”

Mary Ann Nicholls: “Polly” Age Features Born on August 26, 1845 in 5'2" tall; brown eyes; dark Dawes Court, Shoe Lane, off complexion; brown hair Fleet Street. turning grey; five front teeth At the time of her death the East missing; two bottom-one top London Observer guessed her front, her teeth are slightly age at 30-35. discoloured. She is described At the inquest her father said as having small, delicate "she was nearly 44 years of age, features with high cheekbones but it must be owned that she and grey eyes. She has a small looked ten years younger." scar on her forehead from a childhood injury. Lifestyle She is described by Emily Holland as "a very clean woman who always seemed to keep to herself." The doctor at the post mortem remarked on the cleanliness of her thighs. She is also an alcoholic. In 1882, William (Polly’s husband) found out that his wife was living as a prostitute and discontinued support payments to her. He won his case after establishing that she was living as a common prostitute. At the time of her death, he had not seen his wife in three years. On 12/2/87 It is said that she was caught "sleeping rough (in the open)"The in Trafalgar Night Square.of the She Crime: was found Thursday, to be destitute August and with no means of sustenance and was sent on to Lambeth Workhouse. 30 through Friday, August 31, 1888. The rain was sharp and frequent and was accompanied by peals of thunder and flashes of lightning. -

Jack the Ripper Book

Year 9 Term 1 b The Whitechapel Killings : How did the Whitechapel Killer evade capture by the Police? Historical Enquiry - Extension Book. Whitechapel Killings Page !1 Year 9 Term 1 b This book contains greater amounts of deeper information and a variety of extension tasks. It is split by areas. Anyone may have a go at the tasks and studying the content. This is EXTENSION - it is to take you BEYOND the class and homework, both of which should be completed first. Part 1: London: 19th C What was London like in the 19th Century? KEY QUESTION: HOW DID SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS HELP THE WHITECHAPEL KILLER IN THE ‘AUTUMN OF TERROR’ OF 1888? 1: Houses, housing and the streets 2: Homelessness and unemployment 3: Pollution, filth and illness 4: Prostitution and alcoholism The conditions in all major cities in the mid to late 19th century were dreadful, but in London, the largest city in the world at the time, things were even worse than in most other places. London was the centre of an enormous Empire, it was a major port, it was a magnate for an enormous immigrant population and had been for centuries. The city was a divided city, and the poor lived in absolute squalor: occasionally attempts were made by philanthropists to help make conditions better, but for the most part, the rich preferred to ignore the poverty, the suffering, the massive unemployment and all the problems that accompanied these. All of these are some of the key factors in understanding why hunting down and catching the Whitechapel Killer, Jack the Ripper, was impossible for the police of the time, though there are others which shall be examined in a later chapter. -

Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper MURDER IN BUCK'S ROW London in the year 1888. On August 30th the weather was cool, the sky was black with smoke from domestic fires, and rain fell; rain and more rain. The late summer and autumn had the heaviest rain of the year. At 9 o’clock on that Thursday night a great fire in London Docks changed the colour of the sky in the East End of London to a deep red. From the dirty streets, dark passages and slum houses of Whitechapel hundreds of people went to watch the fire. Many of them were poor and homeless. They lived and slept in squalid lodging houses. The poorest lived in the streets and slept in doorways. As always, the pubs were crowded and noisy. Alcohol was cheap and it helped people to feel better. Mary Ann Nichols was in ‘The Frying Pan’ pub on the corner of Brick Lane, spending her last pennies on drink. She needed the money to pay for a bed in the ‘White House’, her lodging house in Flower and Dean Street. But Mary Ann needed alcohol too, and she was drinking too much. Later that night she tried to get a bed at Cooley’s lodging house in Thrawl Street, but she had to leave because she had no money. So she walked around the wet, cold streets hoping to earn something. One of the poorest areas in London, Whitechapel did not have many street lamps. The streets were dark, gloomy and dangerous. Mary Ann Nichols was still walking the streets when her friend Ellen Holland saw her at 2.30 a.m. -

JACK the RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders) VICTIMS

JACK THE RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders) VICTIMS 03 Apr 1888 - 13 Feb 1891 Compiled by Campbell M gold (2012) (This material has been compiled from various unconfirmed sources) CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- Introduction The following material is a basic compilation of "facts" related to the Whitechapel murders. The sources include reported medical evidence, police comment, and inquest reports - as far as possible Ripper myths have not been considered. Additionally, where there was no other source available, newspaper reports have been used sparingly. No attempt has been made to identify the perpetrator of the murders and no conclusions have been made. Consequently, the reader is left to arrive at their own conclusions. Eleven Murders The Whitechapel Murders were a series of eleven murders which occurred between Apr 1888 and Feb 1891. Ten of the victims were prostitutes and one was an unidentified female (only the torso was found). It was during this period that the Jack the Ripper murders took place. Even today, 2012, it still remains unclear as to how many victims Jack the Ripper actually killed. However, it is generally accepted that he killed at least four of the "Canonical" five. Some researchers postulate that he murdered only four women, while others say that he killed as many as seven or more. Some earlier deaths have also been speculated upon as possible Ripper victims. 1 The murders were considered too much for the local Whitechapel (H) Division C.I.D, headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid, to handle alone. Assistance was sent from the Central Office at Scotland Yard, after the Nichols murder, in the persons of Detective Inspectors, Frederick George Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews, together with a team of subordinate officers. -

The Theatrical Histories of Jack the Ripper

Murder, Myth, and Melodrama: The Theatrical Histories of Jack the Ripper by Justin Allen Blum A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Justin Allen Blum, 2015 Murder, Myth, and Melodrama: The Theatrical Histories of Jack the Ripper Justin Allen Blum Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies University of Toronto 2015 Abstract In 1888, several murders in the London boroughs of Whitechapel and Spitalfields became the first modern serial killings reported by mass-circulation daily media. These were identified with “Jack the Ripper,” a name that still resonates in popular culture and entertainment. This dissertation looks to the theatrical culture of London, arguing that theatre and drama provided models for the creation of this figure, which has the cultural status of a “myth” in the sense defined by Roland Barthes. Drawing on the vocabulary of Barthes and on Diana Taylor’s idea of the “scenario” as a unit of enacted narrative with mythic cultural force, four case studies from a variety of London stages trace how ideas and anxieties about urban modernity were taken from the stage and used by newspaper writers and the public to imagine the Ripper. The first looks at a production of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde that took place at the same time as the murders, showing how these modeled the killer for a middle-class audience. The second describes an illegal basement theatre in the -

Exhibition Hall September 2012

Exhibition Hall September 2012 Well, this is late. Very late. Things happen, zines take time, even I get tired. I’m very happy to say that this issue is now here and has more stuff in it than I expected. The next issue of ExHall will hopefully be done in time for SteamCon. I hope so. There’s plenty of time and a lot of stuff to review and talk about before that happens. SteamCon’ll be my first Steampunk convention since Nova Albion 2011. I miss the costumes, the conver- sation, the absolute sense of AWESOME that comes with ‘em and it’ll be nie to see my Seattle folks again. I think I’m speaking, I haven’t heard back from ‘em yet, but I will certainly be doing an episode or two of #HardCopy- Podcast while I’m there. Been getting s lot of books lately, which I enjoy, but I am realising that I’m not exactly great at the whole reading fast thing, which is pretty much what it takes to be a reviewer. I guess I’m not a reviewer. I’m more of a guy who reads a book and writes about it. Maybe that’s what a reviewer is. Maybe... The biggest thing that’s happened in the time between this and the last issue? Well, that’s probably World- Con in Chicago. I love me some WorldCon, and this year your intrepid co-editors were both nominated for 4 Hugos each. After winning for The Drink Tank last year, we weren’t expecting anything this year, and that’s ex- actly what we got. -

The Identity of Jack the Ripper and His Century-Long Legacy

- Unsolved Mysteries: The Identity of Jack the Ripper and His Century-Long Legacy An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Kyli Lynn Shellenberger Thesis Advisor Dr. Anthony Edmonds Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2003 Expected Date of Graduation' May 3, 2003 ,_ 't" c ' ; ( - Abstract Jack the Ripper was a serial killer who stalked prostitutes in the East End of London in 1888. His identity remains unknown, despite the life-long attempts of a multitude of individuals to uncover the truth behind the mystery. The legacy of Jack the Ripper has garnered the attention of individuals all over the world for more than a century, which was due in part to the large amount of media coverage regarding the case. This project focuses on each of the murders and the victims, the possible perpetrators, and the causes for the worldwide craze surrounding Jack the Ripper. I researched the lifestyle of London inhabitants in 1888 and the impact ofthe press coverage of the case. My tour ofthe area and firsthand experiences with the East End were a part of this process as well. Although my research did not uncover a definitive solution to the mystery, I provide hypotheses concerning the identity of Jack the Ripper and the foundation of his legacy. - 2 - Acknowledgements -lowe a great deal of thanks to Dr. Anthony Edmonds for his insight, direction, and influence in the production of this project. 1 thank him for providing me the opportunities to experience London and all it had to offer, and to understand what it means to be passionate about something. -

The Whitechapel Murders)

JACK THE RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders) SUSPECTS and WITNESSES 1888 - 1891 Compiled by Campbell M Gold (2012) (This material has been compiled from various unconfirmed sources) CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- Introduction The following material is a brief overview of the Police Suspects in the Whitechapel murders - 1888- 1891. The Victims The Whitechapel Murders were a series of eleven murders which occurred between Apr 1888 and Feb 1891. Ten of the victims were prostitutes and one was an unidentified female (only the torso was found). It was during this period that the Jack the Ripper murders took place. Even today, 2012, it still remains unclear as to how many victims Jack the Ripper actually killed. However, it is generally accepted that he killed at least four of the "Canonical" five. --()-- 1 Victims - Colour Code - Green - Murders prior to the Canonical Five Murders - Yellow - The canonical Five Murders - Blue - Murders after the Canonical Five Murders Date Victim Location Assaulted, raped, and robbed in Entrance to Brick Lane, Osborn Street, Whitechapel Tue, 03 Apr 1888 Emma Elizabeth Smith Died in London Hospital, Wed, 04 Apr 1888 of peritonitis resulting from her injuries 1st floor landing, George Yard Buildings, George Tue, 07 Aug 1888 Martha Tabram Yard (now Gunthorpe Street), Whitechapel Fri, 31 Aug 1888 Mary Ann (Polly) Nichols Buck's Row (now Durward Street), Whitechapel Sat, 08 Sep 1888 Annie Chapman Rear Yard, 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields Dutfield's Yard, at side of 40 Berner Street (now Sun, 30 Sep 1888