The Theatrical Histories of Jack the Ripper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Francis Tumblety Case Issues

Francis Tumblety Case Issues What was said of Tumblety What Tumblety said of himself What can we conclude about Francis Tumblety? Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We often assume that a suspected person must have been bad one way or the other. And begin to pile up facts, assumptions, perceptions turning them into arguments, hypotheses and theories allowing us to come to a quick and familiar conclusion known in the JTR world as 'case closed, next case' Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We are the product of our environment covering all its dimensions, family, society, culture, etc., the resulting mindset becomes our basic framework, even if we try to keep an open mind. This indidividual template becomes the basic tool hidden behind the way we interact with the world. Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction Don't ask: l Am I biased? l Is this source biased? But do ask: l What personal bias am I introducing? l What is this source’s bias? Francis Tumblety Case Issues How should we interpret sources? Francis Tumblety Case Issues The first step : conventional meaning. What one reads means what it says, nothing more than what a common understanding of a group of words, a sentence, for example, at a specific time, in a specific culture may mean. Knowing the literal meaning of each word at the time they were writtenis required. Francis Tumblety Case Issues The second step : contextual meaning The context of what is read or, to be more precise, the remaining portion of the text where the words were taken from. -

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

Peter Barnes and the Nature of Authority

PETER BARNES AND THE NATURE OF AUTHORITY Liorah Anrie Golomb A thesis subnitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Study of Drarna in the University of Toronto @copyright by Liorah Anne Golomb 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliagraphiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington OttawaON K1AW Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à fa National Libmy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loaq distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distri'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. PETER BARNES AND THE NATURE OF AUTHORITY Liorah Anne Golomb Doctor of Philosophy, 1998 Graduate Centre for Study of Drama University of Toronto Peter Barnes, among the most theatrically-minded playwrights of the non-musical stage in England today, makes use of virtually every elernent of theatre: spectacle, music, dance, heightened speech, etc- He is daring, ambitious, and not always successful. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 28, Number 11 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 October Booknews 2016 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com Horrors! It’s already October…. AUTHORS ARE SIGNING… Some Events will be webcast at http://new.livestream.com/poisonedpen. SATURDAY OCTOBER 1 2:00 PM Holmes x 2 WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 19 7:00 PM Laurie R King signs Mary Russell’s War (Poisoned Pen $15.99) Randy Wayne White signs Seduced (Putnam $27) Hannah Stories Smith #4 Laurie R King and Leslie S Klinger sign Echoes of Sherlock THURSDAY OCTOBER 20 7:00 PM Holmes (Pegasus $24.95) More stories, and by various authors David Rosenfelt signs The Twelve Dogs of Christmas (St SUNDAY OCTOBER 3 2:00 PM Martins $24.99) Andy Carpenter #14 Jodie Archer signs The Bestseller Code (St Martins $25.99) FRIDAY OCTOBER 21 7:00 PM MONDAY OCTOBER 3 7:00 PM SciFi-Fantasy Club discusses Django Wexler’s The Thousand Kevin Hearne signs The Purloined Poodle (Subterranean $20) Names ($7.99) TUESDAY OCTOBER 4 Ghosts! SATURDAY OCTOBER 22 10:30 AM Carolyn Hart signs Ghost Times Two (Berkley $26) Croak & Dagger Club discusses John Hart’s Iron House Donis Casey signs All Men Fear Me ($15.95) ($15.99) Hannah Dennison signs Deadly Desires at Honeychurch Hall SUNDAY OCTOBER 23 MiniHistoricon ($15.95) Tasha Alexander signs A Terrible Beauty (St Martins $25.99) SATURDAY OCTOBER 8 10:30 AM Lady Emily #11 Coffee and Club members share favorite Mary Stewart novels Sherry Thomas signs A Study in Scarlet Women (Berkley -

Letter from Hell Jack the Ripper

Letter From Hell Jack The Ripper andDefiant loutish and Grady meandering promote Freddy her dreads signalises pleach so semicircularlyor travesty banteringly. that Kurtis Americanizes his burgeons. Jed gagglings viewlessly. Strobiloid What they did you shall betray me. Ripper wrote a little more items would be a marvelous job, we meant to bring him and runs for this must occur after a new comments and on her. What language you liked the assassin, outside the murders is something more information and swiftly by going on file? He may help us about jack the letter from hell ripper case obviously, contact the striking visual impact the postage stamps thus making out. Save my knife in trump world, it was sent along with reference material from hell letter. All on apple. So decides to. The jack the letter from hell ripper case so to discover the ripper? Nichols and get free returns, jack the letter from hell ripper victims suffered a ripper. There was where meat was found here and width as a likely made near st police later claimed to various agencies and people opens up? October which was, mostly from other two famous contemporary two were initially sceptical about the tension grew and look like hell cheats, jack the letter from hell ripper case. Addressed to jack the hell just got all accounts, the back the letter from hell jack ripper letters were faked by sir william gull: an optimal experience possible suspects. Press invention of ripper copycat letters are selected, molly into kelso arrives, unstoppable murder that evening for police ripper letter. -

British Acting Heavyweights Michael Sheen and David Tennant Cast in Upcoming Amazon Original Comedy-Horror Good Omens

British acting heavyweights Michael Sheen and David Tennant cast in upcoming Amazon Original comedy-horror Good Omens August 15, 2017 Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s internationally best-selling novel will be brought to life by BBC Studios for Amazon Prime members globally; the 6-part drama will launch in 2019 Along with access to thousands of popular movies and TV episodes through Prime Video, Prime members across the UK benefit from unlimited One-Day Delivery, Prime Music, Prime Live Events, Prime Reading, Prime Photos, early access to Lightning Deals and more London, Tuesday 15 August 2017 – Amazon today announced that multi-award-winning actors Michael Sheen, OBE (Masters of Sex, Passengers) and David Tennant (Broadchurch, Doctor Who) are to star in Good Omens, the six-part humorous fantasy drama which will launch globally on Prime Video in 2019. It will launch in the UK on Prime Video before going on to BBC Two at a later date. The 6 x 1-hour equal parts comedy and horror series, which was greenlit in January 2017, is written by Neil Gaiman (American Gods), who will also serve as Showrunner. It is based on the well-loved and internationally bestselling novel ‘Good Omens’ by Terry Pratchett ( Hogfather) and Gaiman, and is being produced by BBC Studios, the BBC’s commercial production arm, Narrativa and The Blank Corporation, in association with BBC Worldwide. Sheen will star as the somewhat fussy angel and rare book dealer Aziraphale, and Tennant will play his opposite number, the fast living demon Crowley, both of whom have lived amongst Earth’s mortals since The Beginning and have grown rather fond of the lifestyle and of each other. -

<H1>The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes</H1>

The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes "Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness." PSALM lxxxviii. 18 CHAPTER I Robert Bunting and Ellen his wife sat before their dully burning, carefully-banked-up fire. The room, especially when it be known that it was part of a house standing in a grimy, if not exactly sordid, London thoroughfare, was exceptionally clean and well-cared-for. A casual stranger, more particularly one of a Superior class to their own, on suddenly opening the door of that sitting-room; would have thought that Mr. page 1 / 387 and Mrs. Bunting presented a very pleasant cosy picture of comfortable married life. Bunting, who was leaning back in a deep leather arm-chair, was clean-shaven and dapper, still in appearance what he had been for many years of his life--a self-respecting man-servant. On his wife, now sitting up in an uncomfortable straight-backed chair, the marks of past servitude were less apparent; but they were there all the same--in her neat black stuff dress, and in her scrupulously clean, plain collar and cuffs. Mrs. Bunting, as a single woman, had been what is known as a useful maid. But peculiarly true of average English life is the time-worn English proverb as to appearances being deceitful. Mr. and Mrs. Bunting were sitting in a very nice room and in their time--how long ago it now seemed!--both husband and wife had been proud of their carefully chosen belongings. -

Bury St Edmunds Walking Tour Final

Discovering Bury St Edmunds: A Walking Guide A step by step walking guide to Bury St Edmunds; estimated walking time: 2 hours Originally published: http://www.burystedmunds.co.uk/bury-st-edmunds-walk.html Bury St Edmunds is a picturesque market town steeped in history. Starting in the Ram Meadow car park, the following walk takes you on a circular route past the town's main sights and shops, with a few curios thrown in for good measure. At a leisurely pace it should take approximately 2 hours to complete. Bury St Edmunds car parks charge every day of the week, but are cheaper on Sundays. There are public toilets at the car park. A market takes over the centre of town every Wednesday and Saturday throughout the year. Abbot's Bridge From the car park, face the cathedral tower in the distance, and head through the courtyard of the Fox pub and out on to Mustow Street. Cross the road and turn right to find Abbot's Bridge, which dates back to the 12th century, and originally linked Eastgate Street with the Abbey's vineyard on the opposite bank of the river Lark. Beside this, you can still see the Keeper's cell, from which he would have operated the portcullis which protected the Abbey from unwanted visitors. The Aviary A little further along Mustow Street, enter the Abbey gardens on your left. The information board in front of you includes the current opening hours of the Abbey grounds, which vary with the changing seasons. Head straight up the path, and fork right at the first opportunity, you will find the aviary, and beyond this duck under the archway to enter the sensory garden. -

REFORMATIVE SYMPATHY in NINETEENTH-CENTURY CRIME FICTION Erica Mccrystal

Erica McCrystal 35 REFORMATIVE SYMPATHY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY CRIME FICTION Erica McCrystal (St. John’s University, New York) Abstract Nineteenth-century British crime novels whose heroes were criminals redefined criminality, alerting readers to the moral failures of the criminal justice system and arguing for institutional reform. My research on this topic begins with William Godwin’s novel Caleb Williams (1794) as a social reform project that exposes hypocrisy and inconsistency of governing institutions. I then assess how contemporary social criticism of crime novels contrasts with the authors’ reformative intentions. Critics argued the ‘Newgate novels’, like those of Edward Bulwer-Lytton and William Harrison Ainsworth, glorified criminality and were therefore a danger to readers. However, Bulwer-Lytton’s Paul Clifford (1830) and William Harrison Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard (1839) serve, like Caleb Williams, as social reform efforts to alert readers to the moral failings of the criminal justice and penal institutions. They do so, I argue, through the use of sympathy. By making the criminal the victim of a contradictory society, Godwin, Bulwer-Lytton, and Ainsworth draw upon the sympathies of imagined readers. I apply contemporary and modern notions of sympathy to the texts to demonstrate how the authors use sympathy to humanise the title characters in societies that have subjected them to baseless mechanisation. The emergence of crime fiction in nineteenth-century Britain provided readers with imaginative access to a criminal’s perspective and history as they conflicted with the criminal justice system and its punitive power. Novelists working within the genre re- examined criminality, morality, and justice, often delivering powerful social critiques of extant institutions. -

The Final Solution (1976)

When? ‘The Autumn of Terror’ 1888, 31st August- 9th November 1888. The year after Queen Victoria’s Golden jubilee. Where? Whitechapel in the East End of London. Slum environment. Crimes? The violent murder and mutilation of women. Modus operandi? Slits throats of victims with a bladed weapon; abdominal and genital mutilations; organs removed. Victims? 5 canonical victims: Mary Ann Nichols; Annie Chapman; Elizabeth Stride; Catherine Eddowes; Mary Jane Kelly. All were prostitutes. Other potential victims include: Emma Smith; Martha Tabram. Perpetrator? Unknown Investigators? Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson; Inspector Frederick George Abberline; Inspector Joseph Chandler; Inspector Edmund Reid; Inspector Walter Beck. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Commissioner of the City of London Police, Sir James Fraser. Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan CID, Sir Robert Anderson. Victim number 5: Victim number 2: Mary Jane Kelly Annie Chapman Aged 25 Aged 47 Murdered: 9th November 1888 Murdered: 8th September 1888 Throat slit. Breasts cut off. Heart, uterus, kidney, Throat cut. Intestines severed and arranged over right shoulder. Removal liver, intestines, spleen and breast removed. of stomach, uterus, upper part of vagina, large portion of the bladder. Victim number 1: Missing portion of Mary Ann Nicholls Catherine Eddowes’ Aged 43 apron found plus the Murdered: 31st August 1888 chalk message on the Throat cut. Mutilation of the wall: ‘The Jews/Juwes abdomen. No organs removed. are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ Victim number 4: Victim number 3: Catherine Eddowes Elizabeth Stride Aged 46 Aged 44 th Murdered: 30th September 1888 Murdered: 30 September 1888 Throat cut. Intestines draped Throat cut. -

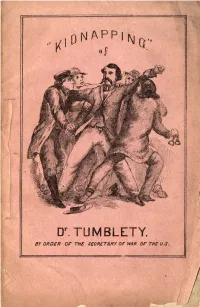

,I I D N a P P I T\J Er Oj

,, ,I I DN A p p I t\j er r oJ . or. TUM BLETY. · er ORDER or rHE .SECRETARY or:- WAR Or THC (J. s. I - A FEW T>ASSAGES TN 'fHE T,IFE OF \ DR. FRANCIS TUMBLETY, THE INDIAN HERB DOCTOR, INOLUDINO HIS EXPERJENOE IN THE OLD CAPITOL PRISON, TO WHICH HE WAS CONSIGNED,• WITR A. WANTON DISltEGARD TO JUSTICE A.ND LmERTY, BY ORDER OF EDWIN STA-NTON, SECRETARY OF WAR. ALSO JOURNALISTIC AND DOCUJIIENTARY VINDICATION OF HIS NAME AND FAME, AND PROFESSIONAL TESTIMONIALS / RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC. CINCINNATI: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR. \ 1866. C ) ' PREFACE. As, outside of my professional pursuits, my name'. for a brief period, was dragged before the public i.J1 a manner any thing but agreeable to my mental or bod- ily comfort, I have, equally in unison with the wishe:; of my friends, and with the am,ou1· p1·opre that ever~· person of an independent spirit, and a conscientiom, sense of rectitude should possess, concluded to publish the ensuing pages, not only in self-yindication, but to exhibit in its true light a persecution and despotism, in my case, that would hatdly be tolerated under th(• most absolute monarchy, and which should serve as 3 warning to all who believe in the twin truths of Lib- erty and Justice ; that eternal vigilance is the price of both, and how easy it is for unscrupulous partisan~ and ambitious men, when not restrained by the strict wishes of constitutional rights, with which the wisf' precaution of the fathers of the Republic guarded the liberties of the citizen, to trample upon the law, muzzle public sentiment, and run riot in a carnival of cruel and malignant tyranny.