Peter Barnes and the Nature of Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belarus Free Theatre Opens up Its Digital Archive to Share 24 Theatrical Productions from the Past 15 Years

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Thursday 2 April 2020 BELARUS FREE THEATRE OPENS UP ITS DIGITAL ARCHIVE TO SHARE 24 THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS FROM THE PAST 15 YEARS WILL ATTENBOROUGH, STEPHEN FRY, ANDREI KHLYVNIUK, DAVID LAN, JULIET STEVENSON & SAM WEST JOIN NEW FAIRY-TALE-INSPIRED CAMPAIGN #LOVEOVERVIRUS 2020 marks the 15th anniversary of Belarus Free Theatre (BFT), the foremost refugee-led theatre company in the UK and the only theatre in Europe banned by its government on political grounds. Ahead of the announcement of the full programme of BFT’s 15th anniversary celebrations, and in response to the coronavirus pandemic, the company will open up its digital archive to make 24 acclaimed stage productions free to watch online, alongside the launch of a new fairy-tale-inspired campaign: #LoveOverVirus 15 YEARS OF THEATRICAL HIGHLIGHTS FREE TO WATCH ONLINE Belarus Free Theatre began 15 years ago this week – on 30 March 2005 – in Minsk under Europe's last surviving dictatorship. Since 2011, the company has been based between Minsk and London where its co-founding Artistic Directors, Natalia Kaliada and Nicolai Khalezin, are political refugees in the UK. New productions are created and rehearsed over Skype before premiering in continually changing underground locations in and around Minsk. Over the past decade, BFT has - through necessity - pioneered creating award-winning theatre at distance and will now share a raft of its theatrical highlights with audiences online at a time when more than a third of the world’s population is adapting to daily life under lockdown. Beginning this Saturday (4 April), and continuing each weekend for the next three months, 24 productions will be made available to watch online on BFT’s YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/BelarusFreeTheatre Each production listed below will air on the date indicated at 8pm GMT and will be available to watch for the following 24 hours. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

The Humor of Red Noses by Peter

LAUGHING AT THE DEVIL: THE HUMOR OF RED NOSES BY PETER BARNES by PAULA JOSIE RODRIGUEZ, B.F.A. A THESIS IN THEATRE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Approved December, 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several people I would like to thank for their motivation and assistance throughout my graduate career at Texas Tech University. I wish to thank my thesis chairperson. Dr. Jonathan Marks for his encouragement, faith, and guidance through the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Professor Christopher Markle for his stimulating insights and criticism throughout the production of Red Noses. Special recognition goes to Dr. George W. Sorensen for recmiting me to Texas Tech University. This thesis would not have been possible without his patience and unwavering commitment to this project. I would also like to thank the cast of Red Noses for their infinite creativity and energy to the production. Finally, I am gratefiil to my friend and editor Deirdre Pattillo for her inmieasurable support, motivation, and assistance in this thesis writing process. n TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 n. ANALYSIS OF THE THEMES AND APPROACHES IN THE WORK OF PETER BARNES 10 m. PRE-PRODUCTION WORK FOR RED NOSES 26 IV. CREATIVE PROCESS AND PRESENTATION 39 V CONCLUSION 60 BIBLIOGRAPHY 68 m CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During World War n, as Allied forces battled fascism and the annihilation of six million Jews had begun, a joke circulated among European Jews: Two Jews had a plan to assassinate Hitler. -

THE ARCHITECT by AIDAN FENNESSY Welcome

THE ARCHITECT BY AIDAN FENNESSY Welcome The Architect is an example of the profound role theatre plays in helping us make sense of life and the emotional challenges we encounter as human beings. Night after night in theatres around the world, audiences come together to experience, be moved by, discuss, and contemplate the stories playing out on stage. More often than not, these stories reflect the goings on of the world around us and leave us with greater understanding and perspective. In this world premiere, Australian work, Aidan Fennessy details the complexity of relationships with empathy and honesty through a story that resonates with us all. In the hands of Director Peter Houghton, it has come to life beautifully. Australian plays and new commissions are essential to the work we do at MTC and it is incredibly pleasing to see more and more of them on our stages, and to see them met with resounding enthusiasm from our audiences. Our recently announced 2019 Season features six brilliant Australian plays that range from beloved classics like Storm Boy to recent hit shows such as Black is the New White and brand new works including the first NEXT STAGE commission to be produced, Golden Shield. The full season is now available for subscription so if you haven’t yet had a look, head online to mtc.com.au/2019 and get your booking in. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. -

Demarcating Dramaturgy

Demarcating Dramaturgy Mapping Theory onto Practice Jacqueline Louise Bolton Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Workshop Theatre, School of English August 2011 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 11 Acknowledgements This PhD research into Dramaturgy and Literary Management has been conducted under the aegis of an Arts and Humanities Research Council Collaborative Doctoral Award; a collaboration between the University of Leeds and West Yorkshire Playhouse which commenced in September 2005. I am extremely grateful to Alex Chisholm, Associate Director (Literary) at West Yorkshire Playhouse, and Professor Stephen Bottoms and Dr. Kara McKechnie at the University of Leeds for their intellectual and emotional support. Special thanks to Professor Bottoms for his continued commitment over the last eighteen months, for the time and care he has dedicated to reading and responding to my work. I would like to take this opportunity to thank everybody who agreed to be interviewed as part of this research. Thanks in particular to Dr. Peter Boenisch, Gudula Kienemund, Birgit Rasch and Anke Roeder for their insights into German theatre and for making me so welcome in Germany. Special thanks also to Dr. Gilli Bush-Bailey (a.k.a the delightful Miss. Fanny Kelly), Jack Bradley, Sarah Dickenson and Professor Dan Rebellato, for their faith and continued encouragement. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

IN the NEXT ROOM Or the Vibrator Play

47th Season • 447th Production JULIANNE ARGYROS STAGE / SEPTEMBER 26 - OCTOBER 17, 2010 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING aRTISTIC DIRECTOR aRTISTIC DIRECTOR presents IN THE NEXT ROOM or the vibrator play BY Sarah Ruhl John Arnone David Kay Mickelsen Daniel Ionazzi Jim Ragland SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN ORIGINaL MUSIC/SOUND DESIGN Philip D. Thompson Jackie S. Hill Kathryn Davies* DIaLECT COaCH PRODUCTION MaNaGER STaGE MaNaGER DIRECTED BY Casey Stangl Jean and Tim Weiss HONORaRY PRODUCERS Original Broadway Production by Lincoln Center Theater, New York City, 2009. IN THE NEXT ROOM or the vibrator play was originally commissioned and produced by Berkeley Repertory Theatre, Berkeley, CA, Tony Taccone, Artistic Director/Susan Medak, Managing Director. IN THE NEXT ROOM or the vibrator play was developed at New Dramatists. IN THE NEXT ROOM or the vibrator play is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. In the Next Room • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Catherine Givings .......................................................................... Kathleen Early* Dr. Givings ...................................................................................... Andrew Borba* Annie ...................................................................................................... Libby West* Sabrina Daldry ................................................................................. Rebecca Mozo* Mr. Daldry .......................................................................................... -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Vimeo Link for ALL of Bruce Jackson's and Diane

Virtual March 23, 2021 (42:8) Peter Medak: THE RULING CLASS (1972, 154 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the virtual BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to The Ruling Class Zoom link for all Spring 2021 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 Director Peter Medak Writing Peter Barnes wrote the screenplay adaption from his original play. Producers Jules Buck and Jack Hawkins Music John Cameron Cinematography Ken Hodges Editing Ray Lovejoy Carolyn Seymour....Grace Shelley The film was nominated for Best Actor in a Leading Peter Medak (23 December 1937, Budapest). From Role for Peter O’Toole at the 1973 Academy Awards The Film Encyclopedia, 4th Edition. Ephraim Katz and for the Palme d’Or at the 1972 Cannes Film (revised by Fred Klein & Ronald Dean Nolen). Harper Festival. 2001 NY: “Born Dec. 23, 1937, in Budapest. Escaping Hungary following the crushing of the 1956 Cast uprising, he entered the British film industry that same Peter O'Toole.... Jack Arnold Alexander Tancred year as a trainee at AB-Pathe. Following a long Gurney, 14th Earl of Gurney apprenticeship in the sound, editing, and camera Alastair Sim....Bishop Lampton departments, he became an assistant director, then a Arthur Lowe....Daniel Tucker second-unit director on action pictures. -

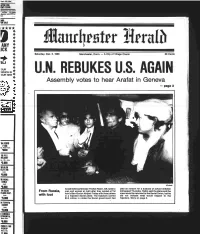

Assembly Votes to Hear Arafat in Geneva — Page 3

linos. 643-7086. M IT08F0R RENT/LEA8E Mllaoe on low cost I rental. Village I Rental. 643-2979or '044. MRS FOR SALE 9 iianrl)rBlfr Mprali ANY UCK Saturday, Dec. 3, 1988 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents =iu OUR WHICH IS . OUR NEW ^ U.N. REBUKES U.S. AGAIN Assembly votes to hear Arafat in Geneva — page 3 ‘84 FORD FtSO :*p. NIca Truck '86 PLY. RELIANT lu*. 4 Dr., Auto *5.900 ‘80 OLDS DELTA 88 Auto *0.009 '80 MERC. 8A8LE Auto AP photo Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin, left, talks to paid as ransom for a busload of school children 84 OLDS From Russia, man and woman at right after they landed at Tel kidnapped Thursday. Rabin said the plane and the ITLA88 SUP. Aviv’s Ben-Gurion Airport Friday with three others crew would be returned to the Soviet Union, but he Auto with loot in a hijacked Soviet plane. The hijackers carried did not indicate what would happen to the *5.090 $3.3 million in rubles the Soviet government had hijackers. Story on page 3. 84 TOYOTA CAMRY Auto 13 LINCOLN INTINENTAL Mum. AmYo *aooo FORD F-150 PICKUP BIm K Std. (7 0 0 0 Weather N. Mexico murder victim U.N. raps REGIONALWEATHER Aocu-Weatfter* forecast for Saturday is Andover man’s brother U.S. again Daytime CorKlitions and High Temperatures An Andover man’s brother was Aibuquerque police have issued Jeanne Wiit and Famigiietta one of three people killed Tuesday a warrant for the arrest of a New were both shot in the head, police Y in a brutal shooting spree in a Jersey man suspected in the said. -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically.