Jack the Ripper Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Francis Tumblety Case Issues

Francis Tumblety Case Issues What was said of Tumblety What Tumblety said of himself What can we conclude about Francis Tumblety? Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We often assume that a suspected person must have been bad one way or the other. And begin to pile up facts, assumptions, perceptions turning them into arguments, hypotheses and theories allowing us to come to a quick and familiar conclusion known in the JTR world as 'case closed, next case' Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We are the product of our environment covering all its dimensions, family, society, culture, etc., the resulting mindset becomes our basic framework, even if we try to keep an open mind. This indidividual template becomes the basic tool hidden behind the way we interact with the world. Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction Don't ask: l Am I biased? l Is this source biased? But do ask: l What personal bias am I introducing? l What is this source’s bias? Francis Tumblety Case Issues How should we interpret sources? Francis Tumblety Case Issues The first step : conventional meaning. What one reads means what it says, nothing more than what a common understanding of a group of words, a sentence, for example, at a specific time, in a specific culture may mean. Knowing the literal meaning of each word at the time they were writtenis required. Francis Tumblety Case Issues The second step : contextual meaning The context of what is read or, to be more precise, the remaining portion of the text where the words were taken from. -

The Welshman Who Knew Mary Kelly

February/March 2018 No. 160 PAUL WILLIAMS on The Welshman Who Knew Mary Kelly STEPHEN SENISE JAN BONDESON HEATHER TWEED NINA and HOW BROWN VICTORIAN FICTION THE LATEST BOOK REVIEWS Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 160 February / March 2018 EDITORIAL: CHANGING FASTER NOT BETTER? Adam Wood THE WELSHMAN WHO KNEW MARY KELLY Paul Williams GEORGE WILLIAM TOPPING HUTCHINSON: ‘TOPPY’ Stephen Senise FROM RIPPER SUSPECT TO HYPERPEDESTRIAN: THE STRANGE CAREER OF BERESFORD GREATHEAD Jan Bondeson LULU - THE EIGHTH WONDER OF THE WORLD Heather Tweed WOMAN’S WORK: AN ALTERNATIVE METHOD OF CAPTURING THE WHITECHAPEL MURDERER PART TWO Nina and Howard Brown VICTORIAN FICTION: THE WITHERED ARM By THOMAS HARDY Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.mangobooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No. 160, February / March 2018, including the compilation of all materials and the unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items are copyright © 2018 Ripperologist/Mango Books. -

Mitre Square Revisited News Reports, Reviews and Other Items Are Copyright © 2009 Ripperologist

RIPPEROLOGIST MAGAZINE Issue 104, July 2009 QUOTE FOR JULY: Andre the Giant. Jack the Ripper. Dennis the Menace. Each has left a unique mark in his respective field, whether it be wrestling, serial killing or neighborhood mischief-making. Mr. The Entertainer has similarly ridden his own mid-moniker demonstrative adjective to the top of the eponymous entertainment field. Cedric the Entertainer at the Ryman - King of Comedy Julie Seabaugh, Nashville Scene , 30 May 2009. We would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance given by Features the following people in the production of this issue of Ripperologist: John Bennett — Thank you! Editorial E- Reading The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed Paul Begg articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist are those of the authors and do not necessarily Suede and the Ripper reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of Ripperologist or Don Souden its editors. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Hell on Earth: The Murder of Marie Suchánková - Ripperologist and its editorial team. Michaela Kořistová We occasionally use material we believe has been placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of some - City Beat: PC Harvey thing we have published we will be pleased to make a prop - Neil Bell and Robert Clack er acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No. 104 July 2009, including the co mpilation of al l materials and the unsigned articles, essays, Mitre Square Revisited news reports, reviews and other items are copyright © 2009 Ripperologist. -

VICTIMS 8Th September of JACK 1888 the RIPPER Born 1841

Worksheets from RJ Tarr and M. Ellis at www.activehistory.co.uk 2. THE STORY OF POLLY NICHOLS Mary Anne Nichols or ‘Polly’ as she was known to her friends was born on 26th August 1845 in Dean Street, Whitechapel. Her father, Edward Walker was a locksmith. In January 1864 she married William Nichols, a printer’s machinist. The couple went to live with Polly’s father. They stayed there about ten years. In 1874 they set up home for themselves at 6D Peabody Buildings, Stamford Street. They had five children: Edward (1866), Percy (1868), Alice (1870), Eliza (1877) and Henry (1879). Despite all the years they spent together, Polly and William’s marriage ended in 1880. Polly lived in the Lambeth workhouse from 6 September 1880 until 31 May 1881. William paid Polly an allowance of 5 shillings a week during this time until he found out that she had started living with another man. Polly’s remaining years were spent in workhouses and doss houses. Between 24th April 1882 and 24 March 1883 she lived at Lambeth workhouse. There is a gap of four years when Polly lives with her father again, but they quarrelled because Polly was a heavy drinker. She left her father and lived with a blacksmith called Thomas Drew. On 25th October 1887 she stayed at St Giles workhouse. Then, from 26 October to 2 December 1887 she stayed at the Strand Workhouse. On 19th December she returned to Lambeth workhouse but was thrown out ten days later. On 4 January 1888 she was admitted to the Mitcham Workhouse, but transferred back to Lambeth on 4 April 1888. -

,I I D N a P P I T\J Er Oj

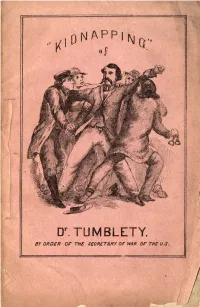

,, ,I I DN A p p I t\j er r oJ . or. TUM BLETY. · er ORDER or rHE .SECRETARY or:- WAR Or THC (J. s. I - A FEW T>ASSAGES TN 'fHE T,IFE OF \ DR. FRANCIS TUMBLETY, THE INDIAN HERB DOCTOR, INOLUDINO HIS EXPERJENOE IN THE OLD CAPITOL PRISON, TO WHICH HE WAS CONSIGNED,• WITR A. WANTON DISltEGARD TO JUSTICE A.ND LmERTY, BY ORDER OF EDWIN STA-NTON, SECRETARY OF WAR. ALSO JOURNALISTIC AND DOCUJIIENTARY VINDICATION OF HIS NAME AND FAME, AND PROFESSIONAL TESTIMONIALS / RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC. CINCINNATI: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR. \ 1866. C ) ' PREFACE. As, outside of my professional pursuits, my name'. for a brief period, was dragged before the public i.J1 a manner any thing but agreeable to my mental or bod- ily comfort, I have, equally in unison with the wishe:; of my friends, and with the am,ou1· p1·opre that ever~· person of an independent spirit, and a conscientiom, sense of rectitude should possess, concluded to publish the ensuing pages, not only in self-yindication, but to exhibit in its true light a persecution and despotism, in my case, that would hatdly be tolerated under th(• most absolute monarchy, and which should serve as 3 warning to all who believe in the twin truths of Lib- erty and Justice ; that eternal vigilance is the price of both, and how easy it is for unscrupulous partisan~ and ambitious men, when not restrained by the strict wishes of constitutional rights, with which the wisf' precaution of the fathers of the Republic guarded the liberties of the citizen, to trample upon the law, muzzle public sentiment, and run riot in a carnival of cruel and malignant tyranny. -

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/[14927] Clare Smith Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith University of Wales: Trinity St. David United Kingdom Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8 ISBN 978-1-137-59999-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59999-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938047 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author has/have asserted their right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accor- dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. -

Jack the Ripper

Year 8 Home Learning, January 2021 (Jack the Ripper) th Lesson 2: What was Whitechapel like in the 19 Century? LO: To be able to explain what the conditions of Whitechapel, London were like at the time of the Ripper murders. Success criteria: ❑ I can describe the events of the Jack the Ripper case. ❑ I can explain what it was like in Whitechapel in the 1800s ❑ I can analyse why these conditions might have had an impact on the Jack the Ripper case. Suggested video links: ● (Jack the Ripper story): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ofnp-zucJxE th ● (18 Century Whitechapel): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQQCBZdnkdY Key takeaway knowledge: • East end London was poor • Whitechapel in the east end was extremely poor • People lived in cramped housing • There was lots of crime • Life was extremely difficult Year 8 Home Learning, January 2021 (Jack the Ripper) Main activity Summarise the story of the murders by summarising each paragraph in 1-2 bullet points on the right-hand side, then give each paragraph a title on the left-hand side. Paragraph The story of Jack the Ripper from the BBC Summarise in 1 title or 2 bullet points. The identity of the killer of five - or possibly six - women in the East End of London in 1888 has remained a mystery, but the case has continued to horrify and fascinate. Between August and November 1888,the Whitechapel area of London was the scene of five brutal murders. The killer was dubbed 'Jack the Ripper'. All the women murdered were prostitutes, and all except for one - Elizabeth Stride - were horribly mutilated. -

Whitechapel's Wax Chamber of Horrors, 1888

Whitechapel’s Wax Chamber of Horrors, 1888 By MIKE HAWLEY A waxwork ‘chamber of horrors’1 museum exhibiting ‘vilely executed waxen figures’2 of the most notorious homicides of Victorian times operated in 1888 at just a few minutes’ walking distance from the location of the Mary Ann Nichols murder scene. The museum’s main attraction were images of the Ripper victims which were added to the display as they were murdered! By February 1889, the museum displayed a total of six images of the murdered women,3 beginning with the unfortunate Martha Tabram, who had met her death on 7 August 1888. In his 1892 memoirs, Worship Street Police Court Magistrate Montague Williams recalled his walk through this chamber of horrors in early September 1888: There lay a horrible presentment in wax of Matilda Turner [Martha Tabram], the first victim, as well as one of Mary Ann Nichols, whose body was found in Buck’s Row. The heads were represented as being nearly severed from the bodies, and in each case there were shown, in red paint, three terrible gashes reaching from the abdomen to the ribs.4 Not only did the proprietor of the waxwork museum operate a chamber of horrors, but he also offered live entertainment nightly in the adjacent building.5 Ever cognizant of the money-making formula consisting of, first, satisfying the public’s desire for vice - in this case violence against women – and, secondly, adding a pinch of sex, the proprietor had as the main attraction of the show a tough young lady named Miss Juanita. -

Dalley Quinci Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper BY: QUINCI DALLEY Who was Jack the Ripper u Was an unidentified serial killer u He terrorized the impoverished towns of London in1888 u Nicknamed the Whitechapel Murderer and the Leather Apron When u Terrorized the streets of London in 1888 u First Murder: August 7th u Last: September 10th Victims u Typically female prostitutes from the slums of London u Young to middle age women u At least five women Victims u Mary Ann Nichols u Annie Chapman u Elizabeth Stride u Catherine Eddowes u Mary Jane Kelly u Known as the Canonical 5 How Women Were Killed Slit their throats Removed the internal organs from at least three women Murders u Conducted late at night u Typically close to the end of each month u Murders became more brutal as time went on Investigation u A large team of policemen went from house to house to investigate throughout Whitechapel u They followed the same steps as modern police work u More than 2,000 people were interviewed u About 300 people were investigated u 80 people were detained u But they never found the perpetrator Suspects Since 1888 100 suspects have been named Making Jack the Ripper and his legacy live on Walter Sickert u Many different theories about Jack the Ripper’s identity were brought forth u One being Victorian Painter Walter Sickert u Polish Migrant u Grandson to Queen Victoria Letters u Letters were allegedly sent from the killer to the London Police u These were to taunt the officers u Talked of gruesome actions and more murders to come Letters u The name “Jack the Ripper” came from the -

AMEER BEN ALI NINA and HOWARD BROWN with the Face of ‘Frenchy’

June 2020 No. 167 AMEER BEN ALI NINA AND HOWARD BROWN with the face of ‘Frenchy’ sheilLa JONES AND JIM BURNS MICHAEL HAWLEY • ADAM WOOD • BRUCE COLLIE SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST VICTORIAN FICTION • PRESS TRAWL the latest book reviewsRipperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 167 JUNE 2020 EDITORIAL: CONTEXT IS KING Adam Wood FRANCIS TUMBLETY AND JOHN WILKES BOOTH’S ERRAND BOY Michael L. Hawley THE SWANSON MARGINALIA: MORE SCRIBBLINGS Adam Wood MRS. BOOTH’S MOST UNUSUAL ENQUIRY BUREAU Sheilla Jones and Jim Burns CENTRAL NEWS Bruce Collie Spotlight on Rippercast: THE ROYAL CONSPIRACY A-GO-GO Part One AMEER BEN ALI AND AN ACTOR’S TALE Nina and Howard Brown Press Trawl THE SHORT REIGN OF LEATHER APRON VICTORIAN FICTION Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No.