Dr. Francis Tumblety's Two Year Sojourn in the Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francis Tumblety Case Issues

Francis Tumblety Case Issues What was said of Tumblety What Tumblety said of himself What can we conclude about Francis Tumblety? Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We often assume that a suspected person must have been bad one way or the other. And begin to pile up facts, assumptions, perceptions turning them into arguments, hypotheses and theories allowing us to come to a quick and familiar conclusion known in the JTR world as 'case closed, next case' Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We are the product of our environment covering all its dimensions, family, society, culture, etc., the resulting mindset becomes our basic framework, even if we try to keep an open mind. This indidividual template becomes the basic tool hidden behind the way we interact with the world. Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction Don't ask: l Am I biased? l Is this source biased? But do ask: l What personal bias am I introducing? l What is this source’s bias? Francis Tumblety Case Issues How should we interpret sources? Francis Tumblety Case Issues The first step : conventional meaning. What one reads means what it says, nothing more than what a common understanding of a group of words, a sentence, for example, at a specific time, in a specific culture may mean. Knowing the literal meaning of each word at the time they were writtenis required. Francis Tumblety Case Issues The second step : contextual meaning The context of what is read or, to be more precise, the remaining portion of the text where the words were taken from. -

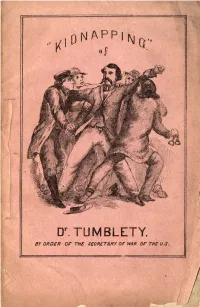

,I I D N a P P I T\J Er Oj

,, ,I I DN A p p I t\j er r oJ . or. TUM BLETY. · er ORDER or rHE .SECRETARY or:- WAR Or THC (J. s. I - A FEW T>ASSAGES TN 'fHE T,IFE OF \ DR. FRANCIS TUMBLETY, THE INDIAN HERB DOCTOR, INOLUDINO HIS EXPERJENOE IN THE OLD CAPITOL PRISON, TO WHICH HE WAS CONSIGNED,• WITR A. WANTON DISltEGARD TO JUSTICE A.ND LmERTY, BY ORDER OF EDWIN STA-NTON, SECRETARY OF WAR. ALSO JOURNALISTIC AND DOCUJIIENTARY VINDICATION OF HIS NAME AND FAME, AND PROFESSIONAL TESTIMONIALS / RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC. CINCINNATI: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR. \ 1866. C ) ' PREFACE. As, outside of my professional pursuits, my name'. for a brief period, was dragged before the public i.J1 a manner any thing but agreeable to my mental or bod- ily comfort, I have, equally in unison with the wishe:; of my friends, and with the am,ou1· p1·opre that ever~· person of an independent spirit, and a conscientiom, sense of rectitude should possess, concluded to publish the ensuing pages, not only in self-yindication, but to exhibit in its true light a persecution and despotism, in my case, that would hatdly be tolerated under th(• most absolute monarchy, and which should serve as 3 warning to all who believe in the twin truths of Lib- erty and Justice ; that eternal vigilance is the price of both, and how easy it is for unscrupulous partisan~ and ambitious men, when not restrained by the strict wishes of constitutional rights, with which the wisf' precaution of the fathers of the Republic guarded the liberties of the citizen, to trample upon the law, muzzle public sentiment, and run riot in a carnival of cruel and malignant tyranny. -

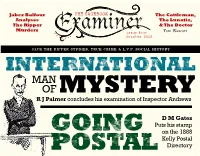

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

AMEER BEN ALI NINA and HOWARD BROWN with the Face of ‘Frenchy’

June 2020 No. 167 AMEER BEN ALI NINA AND HOWARD BROWN with the face of ‘Frenchy’ sheilLa JONES AND JIM BURNS MICHAEL HAWLEY • ADAM WOOD • BRUCE COLLIE SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST VICTORIAN FICTION • PRESS TRAWL the latest book reviewsRipperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 167 JUNE 2020 EDITORIAL: CONTEXT IS KING Adam Wood FRANCIS TUMBLETY AND JOHN WILKES BOOTH’S ERRAND BOY Michael L. Hawley THE SWANSON MARGINALIA: MORE SCRIBBLINGS Adam Wood MRS. BOOTH’S MOST UNUSUAL ENQUIRY BUREAU Sheilla Jones and Jim Burns CENTRAL NEWS Bruce Collie Spotlight on Rippercast: THE ROYAL CONSPIRACY A-GO-GO Part One AMEER BEN ALI AND AN ACTOR’S TALE Nina and Howard Brown Press Trawl THE SHORT REIGN OF LEATHER APRON VICTORIAN FICTION Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No. -

Henry Farquharson, M.P. Joanna Whatley LOOKS at the PAST of the ‘Untrustworthy’ Source of Macnaghten’S ‘Private Information’

March 2020 No. 166 Henry Farquharson, M.P. Joanna whatley LOOKS AT THE PAST OF the ‘Untrustworthy’ Source of Macnaghten’s ‘Private Information’ MICHAEL HAWLEY • martin baggoley from the archives: sex or no sex? SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST • NINA & howard brown the latest book reviewsRipperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 166 March 2020 EDITORIAL: Pandemic, 1892 Adam Wood HENRY RICHARD FARQUHARSON, M.P. The Untrustworthy Source of Macnaghten’s ‘Private Information’? Joanna Whately INSPECTOR ANDREWS’ ORDERS TO NEW YORK CITY, DECEMBER 1888 Michael L. Hawley ELIZA ROSS The Female Burker Martin Baggoley FROM THE ARCHIVES: SEX OR NO SEX? Amanda Howard Spotlight on Rippercast: RIPPERCAST REVIEWS ‘THE FIVE’ BY HALLIE RUBENHOLD MURDERS EXPLAINED BY LONDON BRAINS Nina and Howard Brown VICTORIAN FICTION Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No. -

Download Download

04 Twohig Article.qxd 1/31/2011 1:07 PM Page 70 The “Celebrated Indian Herb Doctor”: Francis Tumblety in Saint John, 1860 PETER L. TWOHIG Francis Tumblety, le « célèbre docteur spécialiste des herbes indiennes », arriva à Saint John à l’été de 1860. Il fut vite en conflit avec la communauté médicale établie et fut même accusé d’homicide involontaire. Cet article s’intéresse au bref séjour de Tumblety à Saint John comme une façon d’illustrer le caractère contesté de la pratique de la médecine au milieu du 19e siècle. La carrière d’un tel praticien jette un éclairage sur l’éventail des choix thérapeutiques qui étaient offerts durant ces années et sur la lutte livrée par la médecine conventionnelle pour limiter ces choix. Francis Tumblety, the “Celebrated Indian Herb Doctor,” arrived in Saint John in the summer of 1860. He quickly became embroiled in conflict with the established medical community and even stood accused of manslaughter. This article examines Tumblety’s brief stay in Saint John as a way of illustrating the contested nature of medical practice in the mid-19th century. Understanding the career of such a practitioner provides insight into the range of therapeutic choices that were available during these years and into the struggle of orthodox medicine to limit these choices. IN THE SUMMER OF 1860, the “Celebrated Indian Herb Doctor” Francis Tumblety arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick. Advertisements began appearing in the local papers, announcing Tumblety’s arrival from the Province of Canada and the opening of his office in American House on King Street.1 Francis Tumblety’s arrival in Saint 1 The earliest advertisements appear in the following newspapers: Morning News (Saint John), 29 June 1860; The Morning Freeman (Saint John), 5 July 1860; and New Brunswicker (Saint John), 17 July 1860. -

{PDF EPUB} the American Murders of Jack the Ripper Tantalizing

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The American Murders of Jack the Ripper Tantalizing Evidence of the Gruesome American Interlude of t Jack the Ripper's identity may finally be known, thanks to DNA. The identity of Jack the Ripper, the notorious serial killer from the late 1800s in England, may finally be known. A DNA forensic investigation published this month by two British researchers in the Journal of Forensic Science identifies Aaron Kosminski, a 23- year-old Polish barber and prime suspect at the time, as the likely killer. The "semen stains match the sequences of one of the main police suspects, Aaron Kosminski," said the study authored by Jari Louhelainen of Liverpool John Moores University and David Miller of the University of Leeds. The murderer dubbed Jack the Ripper killed at least five women from August to November 1888 in the Whitechapel district of London. The study's authors conducted genetic testing of blood and semen on a shawl found near the body of Catherine Eddowes, the killer's fourth victim, whose badly mutilated body was discovered on Sept. 30, 1888. The brutal murders and the mystery behind the killer's identity and motive inspired countless novels, films and theories over the past 130 years. Kosminski, who apparently vanished after the murders, has previously been named as a possible suspect, but his guilt has been a matter of debate and never confirmed. The researchers said they have been analyzing the silk shawl for the past eight years and that to their knowledge "the shawl referred to in this paper is the only piece of physical evidence known to be associated with these murders." Through analysis of fragments of the victim and suspect's mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down solely from one's mother, researchers were able to compare that with samples taken from living descendants of Eddowes and Kosminski. -

Was Charles Le Grand Jack the Ripper?

Inspector THE CASEBOOK Andrews Part Two R. J. Palmer issue two A Red Rose? June 2010 Stewart P. Evans JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY ANOTHER GLIMPSE OF Presented by JOSEPH Chris Phillips LAWENDE THE NOT JUST USUAL SUSPECTS! Tom Wescott introduces us to Charles Le Grand THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 2 June 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of signed issue two articles, essays, letters, reviews and June 2010 other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, Friendship Never Ends pg 3 Collectors Corner transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 6 Expert Advice pg 116 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- Another Glimpse of On The Case News From Ripper World pg 118 cal, photocopying, recording or any Joseph Lawende other, without the express written per- Chris Phillips pg 7 On The Case Extra mission of Casebook.org. The unau- Feature Story pg 121 Le Grand: The New Prime Suspect thorized reproduction or circulation of Tom Wescott pg 13 Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Dr. Anderson, Dr. Tumblety Liverpool Street to Romford pg 124 whether for monetary gain or not, is & a Voyage to Canada CSI: Whitechapel strictly prohibited and may constitute R. J. Palmer pg 66 Annie Chapman pg 134 copyright infringement as defined in A Red Rose? From the Casebook Archives domestic laws and international agree- Stweart P. -

HOLY SEPULCHRE CEMETERY by E

ROCHESTER HISTORY Edited by Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck City Historian Vol. LXVII Spring, 2005 No. 2 HOLY SEPULCHRE CEMETERY by E. Robert Vogt Bronze statue of Bishop Bernard McQuaid, founder of Holy Sepulchre Cemterx. Cover: All Souls Chapel ROCHESTER HISTORY, published quarterly by Office of the City Historian. Address correspondence to City Historian, Rochester Public Library, 1 \5 South Avenue, Rochester, NY 14604. www.libraryweb.org Subscriptions to the quarterly Rochester History are $8.00 per year by mail. Foreign subscriptions $12.00 per year, $4.00 per copy back issue. Rochester History is funded in part from the Frances Kenyon Publication Fund, established in memory of her sister, Florence Taber Kenyon and her friend Thelma Jeffries. PRESSTEK-4 ©OFFICE OF THE CITY HISTORIAN 2004 A New Vision The story of Holy Sepulchre Cemetery cannot be told without some background of the founder. Bishop Bernard J. McQuaid and his philos- ophy on the mission of a Catholic Cemetery for the newly formed Diocese of Rochester. McQuaid was a man of strong convictions, which developed from his early years when he was orphaned at the age of seven and raised by the Sisters of Charity in New York City. The Sisters gave him an excellent education and when he indicated his desire to study for the priesthood, they arranged for him to attend a Preparatory Seminary in Chambly, Quebec, Canada. He completed final studies at St. Joseph's Seminary, Fordham, New York. He was ordained in 1848. Upon his ordination for the Diocese of New York, he was assigned to pastorates in New Jersey, then part of the New York Diocese. -

Jack the Ripper Book

Year 9 Term 1 b The Whitechapel Killings : How did the Whitechapel Killer evade capture by the Police? Historical Enquiry - Extension Book. Whitechapel Killings Page !1 Year 9 Term 1 b This book contains greater amounts of deeper information and a variety of extension tasks. It is split by areas. Anyone may have a go at the tasks and studying the content. This is EXTENSION - it is to take you BEYOND the class and homework, both of which should be completed first. Part 1: London: 19th C What was London like in the 19th Century? KEY QUESTION: HOW DID SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS HELP THE WHITECHAPEL KILLER IN THE ‘AUTUMN OF TERROR’ OF 1888? 1: Houses, housing and the streets 2: Homelessness and unemployment 3: Pollution, filth and illness 4: Prostitution and alcoholism The conditions in all major cities in the mid to late 19th century were dreadful, but in London, the largest city in the world at the time, things were even worse than in most other places. London was the centre of an enormous Empire, it was a major port, it was a magnate for an enormous immigrant population and had been for centuries. The city was a divided city, and the poor lived in absolute squalor: occasionally attempts were made by philanthropists to help make conditions better, but for the most part, the rich preferred to ignore the poverty, the suffering, the massive unemployment and all the problems that accompanied these. All of these are some of the key factors in understanding why hunting down and catching the Whitechapel Killer, Jack the Ripper, was impossible for the police of the time, though there are others which shall be examined in a later chapter. -

Jack Is a Feminist Issue

June/July 2018 No. 162 A Tribute to Katherine Amin Jack is a Feminist Issue MIICHAEL HAWLEY SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST: COLIN WILSON AT THE 1996 CONFERENCE HEATHER TWEED NINA and HOW BROWN JAN BONDESON THE BIG QUESTION VICTORIAN FICTION THE LATEST BOOK REVIEWS Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 162 June / July 2018 EDITORIAL: WHAT’S IN A NAME? Adam Wood JACK IS A FEMINIST ISSUE Katherine Amin THE NEW YORK WORLD’S E. TRACY GREAVES AND HIS SCOTLAND YARD INFORMANT Michael L Hawley THE BIG QUESTION Did the Police Know the Identity of the Ripper? Spotlight on Rippercast COLIN WILSON AT THE 1996 RIPPER CONFERENCE ZAZEL – THE HUMAN CANNONBALL Heather Tweed BEHIND BRASS BADGES AND IRON BARS Nina and Howard Brown FORD MADOX FORD, MURDER HOUSE DETECTIVE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: GLEAMS FROM THE DARK CONTINENT: THE WIZARD OF SWAZI SWAMP By Charles J Mansford Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

Jack the Ripper - Anonymous Murderer

List of Suspects for Pleasant Places of FL meeting November 2, 2013 Jack the Ripper - Anonymous Murderer It is important to note that Sir Melville Macnaghten, Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in 1889 named three suspects: (1) Aaron Kosminski, a Polish Jew, who lived in Whitechapel and was known to hate women and have strong homicidal tendencies. He was admitted to a lunatic asylum in March 1889; (2) Michael Ostrogg, who was a well-known criminal who spent the majority of his life in prison for theft. He was a con man and sneak thief with 25 or more aliases, and was eventually transferred to a lunatic asylum where he registered himself as a Jewish doctor; and (3) Montague John Druitt, a teacher at a boarding school in Blackheath who was dismissed from his teaching job in late Nov 1888 because of an unspecified ‘serious offence.’ He drowned himself in the Thames in Dec 1888. Macnaghten destroyed all the documents pointing to Druitt. In fact, all Sir Melville Macnaghten's personal files - he headed the CIS and had first hand knowledge of Scotland Yard's entire investigation - simply "vanished" shortly after his death. Inspector Abberline, heading the Ripper investigation, discredited Macnaghten’s suspects. He named his own suspect, George Chapman, whose real name was Severin Klosowski, a Polish barber’s assistant in Whitechapel who poisoned 3 wives and was hanged April 7, 1903. NOTE: Although he named Chapman, Chief Inspector Abberline's presentation walking stick is still preserved at Bramshill Police Staff College where the inscription reveals that the stick was presented to Abberline by his team of detectives at the 'conclusion of the inquiry'.