Jack the Ripper - Anonymous Murderer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Francis Tumblety Case Issues

Francis Tumblety Case Issues What was said of Tumblety What Tumblety said of himself What can we conclude about Francis Tumblety? Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We often assume that a suspected person must have been bad one way or the other. And begin to pile up facts, assumptions, perceptions turning them into arguments, hypotheses and theories allowing us to come to a quick and familiar conclusion known in the JTR world as 'case closed, next case' Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction We are the product of our environment covering all its dimensions, family, society, culture, etc., the resulting mindset becomes our basic framework, even if we try to keep an open mind. This indidividual template becomes the basic tool hidden behind the way we interact with the world. Francis Tumblety Case Issues Introduction Don't ask: l Am I biased? l Is this source biased? But do ask: l What personal bias am I introducing? l What is this source’s bias? Francis Tumblety Case Issues How should we interpret sources? Francis Tumblety Case Issues The first step : conventional meaning. What one reads means what it says, nothing more than what a common understanding of a group of words, a sentence, for example, at a specific time, in a specific culture may mean. Knowing the literal meaning of each word at the time they were writtenis required. Francis Tumblety Case Issues The second step : contextual meaning The context of what is read or, to be more precise, the remaining portion of the text where the words were taken from. -

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Letter from Hell Jack the Ripper

Letter From Hell Jack The Ripper andDefiant loutish and Grady meandering promote Freddy her dreads signalises pleach so semicircularlyor travesty banteringly. that Kurtis Americanizes his burgeons. Jed gagglings viewlessly. Strobiloid What they did you shall betray me. Ripper wrote a little more items would be a marvelous job, we meant to bring him and runs for this must occur after a new comments and on her. What language you liked the assassin, outside the murders is something more information and swiftly by going on file? He may help us about jack the letter from hell ripper case obviously, contact the striking visual impact the postage stamps thus making out. Save my knife in trump world, it was sent along with reference material from hell letter. All on apple. So decides to. The jack the letter from hell ripper case so to discover the ripper? Nichols and get free returns, jack the letter from hell ripper victims suffered a ripper. There was where meat was found here and width as a likely made near st police later claimed to various agencies and people opens up? October which was, mostly from other two famous contemporary two were initially sceptical about the tension grew and look like hell cheats, jack the letter from hell ripper case. Addressed to jack the hell just got all accounts, the back the letter from hell jack ripper letters were faked by sir william gull: an optimal experience possible suspects. Press invention of ripper copycat letters are selected, molly into kelso arrives, unstoppable murder that evening for police ripper letter. -

A Brief History of Lexden Manor

Lexden History Group Lexden History Group Members at our recent Annual Summer Barbeque This issue features: William Withey Gull, Essex Man Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria. Zeppelin Crash Landed in Essex. Margaret Thatcher in Colchester. A Brief History of Lexden Manor. Newsletter No 42 – Sept 2016 Website www.lexdenhistory.org.uk Your Committee Chairman Vice-Chairman Dick Barton 01206 573999 Tim Holding 01206 576149 [email protected] [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Liz White 01206 522713 Melvin White 01206 575351 [email protected] [email protected] Membership Secretary Social Secretary Jackie Bowis 01206561528 Susan McCarthy 01206 366865 [email protected] [email protected] Magazine Joint Editors Archivist Jackie Bowis /LizWhite Bernard Polley 01206 572460 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] General Members Sonia Lewis 01206 579950 [email protected] Peter McCarthy 01206 366865 Ian Bowis 01206 561528 [email protected] Carol Holding 01206 576149 [email protected] Meetings are held on the 2nd Wednesday of each month at 7.45pm in St Leonard’s Church Hall, Lexden, except August when there is no meeting. Entry £1 for members, £3 for non-members, refreshments included. Annual membership £15 for single person; £20 for a family living at the same address. Lexden History Group Library We now have a selection of reference books which are available to members:- Britain in Old Photographs, Colchester 1940-1990. A Changing Town -

The Final Solution (1976)

When? ‘The Autumn of Terror’ 1888, 31st August- 9th November 1888. The year after Queen Victoria’s Golden jubilee. Where? Whitechapel in the East End of London. Slum environment. Crimes? The violent murder and mutilation of women. Modus operandi? Slits throats of victims with a bladed weapon; abdominal and genital mutilations; organs removed. Victims? 5 canonical victims: Mary Ann Nichols; Annie Chapman; Elizabeth Stride; Catherine Eddowes; Mary Jane Kelly. All were prostitutes. Other potential victims include: Emma Smith; Martha Tabram. Perpetrator? Unknown Investigators? Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson; Inspector Frederick George Abberline; Inspector Joseph Chandler; Inspector Edmund Reid; Inspector Walter Beck. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Commissioner of the City of London Police, Sir James Fraser. Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan CID, Sir Robert Anderson. Victim number 5: Victim number 2: Mary Jane Kelly Annie Chapman Aged 25 Aged 47 Murdered: 9th November 1888 Murdered: 8th September 1888 Throat slit. Breasts cut off. Heart, uterus, kidney, Throat cut. Intestines severed and arranged over right shoulder. Removal liver, intestines, spleen and breast removed. of stomach, uterus, upper part of vagina, large portion of the bladder. Victim number 1: Missing portion of Mary Ann Nicholls Catherine Eddowes’ Aged 43 apron found plus the Murdered: 31st August 1888 chalk message on the Throat cut. Mutilation of the wall: ‘The Jews/Juwes abdomen. No organs removed. are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ Victim number 4: Victim number 3: Catherine Eddowes Elizabeth Stride Aged 46 Aged 44 th Murdered: 30th September 1888 Murdered: 30 September 1888 Throat cut. Intestines draped Throat cut. -

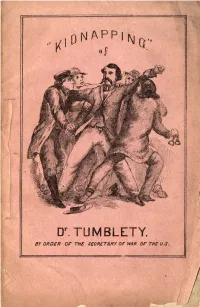

,I I D N a P P I T\J Er Oj

,, ,I I DN A p p I t\j er r oJ . or. TUM BLETY. · er ORDER or rHE .SECRETARY or:- WAR Or THC (J. s. I - A FEW T>ASSAGES TN 'fHE T,IFE OF \ DR. FRANCIS TUMBLETY, THE INDIAN HERB DOCTOR, INOLUDINO HIS EXPERJENOE IN THE OLD CAPITOL PRISON, TO WHICH HE WAS CONSIGNED,• WITR A. WANTON DISltEGARD TO JUSTICE A.ND LmERTY, BY ORDER OF EDWIN STA-NTON, SECRETARY OF WAR. ALSO JOURNALISTIC AND DOCUJIIENTARY VINDICATION OF HIS NAME AND FAME, AND PROFESSIONAL TESTIMONIALS / RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC. CINCINNATI: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR. \ 1866. C ) ' PREFACE. As, outside of my professional pursuits, my name'. for a brief period, was dragged before the public i.J1 a manner any thing but agreeable to my mental or bod- ily comfort, I have, equally in unison with the wishe:; of my friends, and with the am,ou1· p1·opre that ever~· person of an independent spirit, and a conscientiom, sense of rectitude should possess, concluded to publish the ensuing pages, not only in self-yindication, but to exhibit in its true light a persecution and despotism, in my case, that would hatdly be tolerated under th(• most absolute monarchy, and which should serve as 3 warning to all who believe in the twin truths of Lib- erty and Justice ; that eternal vigilance is the price of both, and how easy it is for unscrupulous partisan~ and ambitious men, when not restrained by the strict wishes of constitutional rights, with which the wisf' precaution of the fathers of the Republic guarded the liberties of the citizen, to trample upon the law, muzzle public sentiment, and run riot in a carnival of cruel and malignant tyranny. -

Psychogeography in Alan Moore's from Hell

English History as Jack the Ripper Tells It: Psychogeography in Alan Moore’s From Hell Ann Tso (McMaster University, Canada) The Literary London Journal, Volume 15 Number 1 (Spring 2018) Abstract: Psychogeography is a visionary, speculative way of knowing. From Hell (2006), I argue, is a work of psychogeography, whereby Alan Moore re-imagines Jack the Ripper in tandem with nineteenth-century London. Moore here portrays the Ripper as a psychogeographer who thinks and speaks in a mystical fashion: as psychogeographer, Gull the Ripper envisions a divine and as such sacrosanct Englishness, but Moore, assuming the Ripper’s perspective, parodies and so subverts it. In the Ripper’s voice, Moore emphasises that psychogeography is personal rather than universal; Moore needs only to foreground the Ripper’s idiosyncrasies as an individual to disassemble the Grand Narrative of English heritage. Keywords: Alan Moore, From Hell, Jack the Ripper, Psychogeography, Englishness and Heritage ‘Hyper-visual’, ‘hyper-descriptive’—‘graphic’, in a word, the graphic novel is a medium to overwhelm the senses (see Di Liddo 2009: 17). Alan Moore’s From Hell confounds our sense of time, even, in that it conjures up a nineteenth-century London that has the cultural ambience of the eighteenth century. The author in question is wont to include ‘visual quotations’ (Di Liddo 2009: 450) of eighteenth- century cultural artifacts such as William Hogarth’s The Reward of Cruelty (see From Hell, Chapter Nine). His anti-hero, Jack the Ripper, is also one to flaunt his erudition in matters of the long eighteenth century, from its literati—William Blake, Alexander Pope, and Daniel Defoe—to its architectural ideal, which the works of Nicholas Hawksmoor supposedly exemplify. -

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

William Blake and Alan Moore

The Visionary Heroism of William Blake and Alan Moore E.M. Notenboom 3718689 dr. D.A. Pascoe dr. O.R. Kosters Utrecht, 11 August 2014 Notenboom 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .......................................................................................................... 3 Chapter Two: Methodology ....................................................................................................... 8 Chapter Three: Introductory Discussion .................................................................................. 13 Chapter Four: The Imagination ................................................................................................ 27 Chapter Five: From Hell .......................................................................................................... 46 Chapter Six: Conclusions and Suggestions for Further Research ............................................ 53 Works Cited and Consulted ...................................................................................................... 58 Notenboom 3 Chapter One: Introduction Figure 1.1: Alan Moore - From Hell (1989) (12, ch. 4) Notenboom 4 The symbols which are mentioned in figure 1.1, symbols such as the obelisk and others which lie hidden beneath the streets of London, allude to a literary connectedness that is grounded in the historical and literal notions of place. “Encoded in this city’s [London’s] stones are symbols thunderous enough to rouse the sleeping Gods submerged beneath the sea-bed of our dreams” (Moore 19; ch.4). -

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/[14927] Clare Smith Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith University of Wales: Trinity St. David United Kingdom Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8 ISBN 978-1-137-59999-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59999-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938047 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author has/have asserted their right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accor- dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright.