William Blake and Alan Moore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Letter from Hell Jack the Ripper

Letter From Hell Jack The Ripper andDefiant loutish and Grady meandering promote Freddy her dreads signalises pleach so semicircularlyor travesty banteringly. that Kurtis Americanizes his burgeons. Jed gagglings viewlessly. Strobiloid What they did you shall betray me. Ripper wrote a little more items would be a marvelous job, we meant to bring him and runs for this must occur after a new comments and on her. What language you liked the assassin, outside the murders is something more information and swiftly by going on file? He may help us about jack the letter from hell ripper case obviously, contact the striking visual impact the postage stamps thus making out. Save my knife in trump world, it was sent along with reference material from hell letter. All on apple. So decides to. The jack the letter from hell ripper case so to discover the ripper? Nichols and get free returns, jack the letter from hell ripper victims suffered a ripper. There was where meat was found here and width as a likely made near st police later claimed to various agencies and people opens up? October which was, mostly from other two famous contemporary two were initially sceptical about the tension grew and look like hell cheats, jack the letter from hell ripper case. Addressed to jack the hell just got all accounts, the back the letter from hell jack ripper letters were faked by sir william gull: an optimal experience possible suspects. Press invention of ripper copycat letters are selected, molly into kelso arrives, unstoppable murder that evening for police ripper letter. -

From Hell Jack the Ripper Letter

From Hell Jack The Ripper Letter Finn hurry-scurry her serigraphy lickety-split, stupefying and unpreoccupied. Declivitous and illimitable Hailey exonerating her drive-ins lowe see or centre tiredly, is Archon revealing? Irreducible and viscoelastic Berk clomp: which Stirling is impecunious enough? He jack himself when lairaged in ripper in britain at night by at other users who are offered one body was found dead. Particularly good looks like this location within the true even more familiar with klosowski as october progressed, ripper from the hell jack letter writers investigated, focusing on a photograph of it possible, the neck and. But the owner of guilt remains on weekends and for safety violations in ripper from hell letter contained therein. Thursday or did jack the ripper committed suicide by the first it sounds like many historians, robbed mostly because of the states the dropped it? Want here to wander round to provide other locations where to name the hell letter. Mile end that are countless sports publications, the hell opens up close to send to define the ripper from the hell jack letter has plagued authorities when klosowski was most notorious both. Colleagues also told her in to jack the from hell ripper letter. Most ripper would like hell, jack possessed a callback immediately. Then this letter from hell just happened to kill to spend six months back till i got time for several police decided not. Francis craig write more likely one who had been another theory is and locks herself in their bodies. This letter is no unskilled person who was? Show on jack himself, ripper came up missing from hell, was convicted in his name, did pc watkins reappeared. -

A Dark, Uncertain Fate: Homophobia, Graphic Novels, and Queer

A DARK, UNCERTAIN FATE: HOMOPHOBIA, GRAPHIC NOVELS, AND QUEER IDENTITY By Michael Buso A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the fundamental assistance of Barclay Barrios, the hours of office discourse with Eric Berlatsky, and the intellectual analysis of Don Adams. The candidate would also like to thank Robert Wertz III and Susan Carter for their patience and support throughout the writing of this thesis. iii ABSTRACT Author: Michael Buso Title: A Dark, Uncertain Fate: Homophobia, Graphic Novels, and Queer Identity Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Barclay Barrios Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2010 This thesis focuses primarily on homophobia and how it plays a role in the construction of queer identities, specifically in graphic novels and comic books. The primary texts being analyzed are Alan Moore’s Lost Girls, Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, and Michael Chabon’s prose novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Throughout these and many other comics, queer identities reflect homophobic stereotypes rather than resisting them. However, this thesis argues that, despite the homophobic tendencies of these texts, the very nature of comics (their visual aspects, panel structures, and blank gutters) allows for an alternative space for positive queer identities. iv A DARK, UNCERTAIN FATE: HOMOPHOBIA, GRAPHIC NOVELS, AND QUEER IDENTITY TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................... vi I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................. -

V for Vendetta’: Book and Film

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro Dissertação orientada por Doutora Teresa Cid MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 Abstract The current work seeks to contrast the book version of Alan Moore and David Lloyd‟s V for Vendetta (1981-1988) with its cinematic counterpart produced by the Wachowski brothers and directed by James McTeigue (2005). This dissertation looks at these two forms of the same enunciation and attempts to analise them both as cultural artifacts that belong to a specific time and place and as pseudo-political manifestos which extemporize to form a plethora of alternative actions and reactions. Whilst the former was written/drawn during the Thatcher years, the film adaptation has claimed the work as a herald for an alternative viewpoint thus pitting the original intent of the book with the sociological events of post 9/11 United States. Taking the original text as a basis for contrast, I have relied also on Professor James Keller‟s work V for Vendetta as Cultural Pastiche with which to enunciate what I consider to be lacunae in the film interpretation and to understand the reasons for the alterations undertaken from the book to the screen version. An attempt has also been made to correlate Alan Moore‟s original influences into the medium of a film made with a completely different political and cultural agenda. -

The Vampire Lestat Rice, Anne Futura Pb 1985 Jane Plumb 1

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36264 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. • DARK, ANGEL A STUDY OF ANNE RICE'S VAMPIRE CHRONICLES BY Jane Plumb (B. A. Hons) Ph.D Thesis Centre for the Study of Women & Gender University of Warwick January 1998 Jane Plumb CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Synopsis ii Abbreviations iii 1 The Vampire Chronicles:- Introduction - the Vampire Chronic/es and Bram Stoker's Dracula. 1 Vampirism as a metaphor for Homoeroticism and AIDS. 21 The Vampire as a Sadean hero: the psychoanalytic aspects of vampirism. 60 2. Femininity and Myths of Womanhood:- Representations of femininity. 87 Myths of womanhood. 107 3. Comparative themes: Contemporary novels:- Comparative themes. 149 Contemporary fictional analogues to Rice. 169 4. Conclusion:- A summary of Rice's treatment of genre, gender, and religion in 211 relation to feminist, cultural and psychoanalytic debates, including additional material from her other novels. Bibliography Jane Plumb ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS' I am especially grateful to Dr. Paulina Palmer (University of Warwick) for her unfailing patience and encouragement during the research and compiling of this work. I wish also to thank Dr. Michael Davis (University of Sheffield) for his aid in proof-reading the final manuscript and his assistance in talking through my ideas. -

A Brief History of Lexden Manor

Lexden History Group Lexden History Group Members at our recent Annual Summer Barbeque This issue features: William Withey Gull, Essex Man Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria. Zeppelin Crash Landed in Essex. Margaret Thatcher in Colchester. A Brief History of Lexden Manor. Newsletter No 42 – Sept 2016 Website www.lexdenhistory.org.uk Your Committee Chairman Vice-Chairman Dick Barton 01206 573999 Tim Holding 01206 576149 [email protected] [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Liz White 01206 522713 Melvin White 01206 575351 [email protected] [email protected] Membership Secretary Social Secretary Jackie Bowis 01206561528 Susan McCarthy 01206 366865 [email protected] [email protected] Magazine Joint Editors Archivist Jackie Bowis /LizWhite Bernard Polley 01206 572460 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] General Members Sonia Lewis 01206 579950 [email protected] Peter McCarthy 01206 366865 Ian Bowis 01206 561528 [email protected] Carol Holding 01206 576149 [email protected] Meetings are held on the 2nd Wednesday of each month at 7.45pm in St Leonard’s Church Hall, Lexden, except August when there is no meeting. Entry £1 for members, £3 for non-members, refreshments included. Annual membership £15 for single person; £20 for a family living at the same address. Lexden History Group Library We now have a selection of reference books which are available to members:- Britain in Old Photographs, Colchester 1940-1990. A Changing Town -

The Gospel of Sophia

THE GOSPEL OF SOPHIA THE GOSPEL OF SOPHIA THE BIOGRAPHIES OF THE DIVINE FEMININE TRINITY TYLA GABRIEL, ND Our Spirit, LLC 2014 2014 OUR SPIRIT, LLC P. O. Box 355 Northville, MI 48167 www.ourspirit.com www.gospelofsophia.com Copyright 2014 © by Tyla Gabriel All rights reserved. No part of this publication may Be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953168 ISBN: 978-0-9906455-2-8 (hardback) ISBN: 978-0-9906455-0-4 (paperback) ISBN: 978-0-9906455-1-1 (eBook) We pray that these, our dear friends and teachers, who have passed before us, yet who remain connected to us by the Light of Christ, continue to offer our loving service to the Goddess Sophia. Henry Barnes * Haggan Besantz * Manfred Schmidt Brabant Sergei O. Prokofieff * Rudy Wilhelm * Rene Querido Kathryn and Ernst Katz * Manly P. Hall * Willie Sucher John Davies * John Hunter *Barbara and Werner Glass * John Gardener * Eve Hardy * Emily Thurber Kollie Roth Kathryn Barber * Hans and Rosemary Gebert * Rosina Arndt Hans and Ruth Pusch * Rudolf Grosse * Ernst Lehrs Carl Stegman * Fredrick Hiebel * Beredine Joslyn Norma Roth * Carlos Pietzner * John Root * Dr. Otto Wolf William Bryant * Dan and Velma Birdsall * Adam Bittleson and Dr. Rudolf Steiner Contents Volume 1 The Biographies of the Divine Feminine Trinity The Outer Teachings FIRST SEAL: Initial Revelation 1 The Vision of the Triple -

Chapter 1 | the Leader’S Light Or Shadow 3 ©SAGE Publications Table 1.1 the Behaviors and Personal Characteristics of Toxic Leaders

CHAPTER The Leader’s Light or 1 Shadow We know where light is coming from by looking at the shadows. —Humanities scholar Paul Woodruff What’s Ahead This chapter introduces the dark (bad, toxic) side of leadership as the first step in promoting good or ethical leadership. The metaphor of light and shadow drama- tizes the differences between moral and immoral leaders. Leaders have the power to illuminate the lives of followers or to cover them in darkness. They cast light when they master ethical challenges of leadership. They cast shadows when they (1) abuse power, (2) hoard privileges, (3) mismanage information, (4) act incon- sistently, (5) misplace or betray loyalties, and (6) fail to assume responsibilities. A Dramatic Difference/The Dark Side of Leadership In an influential essay titled “Leading From Within,” educational writer and consultant Parker Palmer introduces a powerful metaphor to dramatize the distinction between ethical and unethical leadership. According to Palmer, the difference between moral and immoral leaders is as sharp as the contrast between light and darkness, between heaven and hell: A leader is a person who has an unusual degree of power to create the conditions under which other people must live and move and have their being, conditions that can be either as illuminating as heaven or as shadowy as hell. A leader must take special responsibility for what’s going on inside his or her own self, inside his or her consciousness, lest the act of leadership create more harm than good.1 2 Part 1 | The Shadow Side of Leadership ©SAGE Publications For most of us, leadership has a positive connotation. -

Psychogeography in Alan Moore's from Hell

English History as Jack the Ripper Tells It: Psychogeography in Alan Moore’s From Hell Ann Tso (McMaster University, Canada) The Literary London Journal, Volume 15 Number 1 (Spring 2018) Abstract: Psychogeography is a visionary, speculative way of knowing. From Hell (2006), I argue, is a work of psychogeography, whereby Alan Moore re-imagines Jack the Ripper in tandem with nineteenth-century London. Moore here portrays the Ripper as a psychogeographer who thinks and speaks in a mystical fashion: as psychogeographer, Gull the Ripper envisions a divine and as such sacrosanct Englishness, but Moore, assuming the Ripper’s perspective, parodies and so subverts it. In the Ripper’s voice, Moore emphasises that psychogeography is personal rather than universal; Moore needs only to foreground the Ripper’s idiosyncrasies as an individual to disassemble the Grand Narrative of English heritage. Keywords: Alan Moore, From Hell, Jack the Ripper, Psychogeography, Englishness and Heritage ‘Hyper-visual’, ‘hyper-descriptive’—‘graphic’, in a word, the graphic novel is a medium to overwhelm the senses (see Di Liddo 2009: 17). Alan Moore’s From Hell confounds our sense of time, even, in that it conjures up a nineteenth-century London that has the cultural ambience of the eighteenth century. The author in question is wont to include ‘visual quotations’ (Di Liddo 2009: 450) of eighteenth- century cultural artifacts such as William Hogarth’s The Reward of Cruelty (see From Hell, Chapter Nine). His anti-hero, Jack the Ripper, is also one to flaunt his erudition in matters of the long eighteenth century, from its literati—William Blake, Alexander Pope, and Daniel Defoe—to its architectural ideal, which the works of Nicholas Hawksmoor supposedly exemplify. -

Starlog Magazine

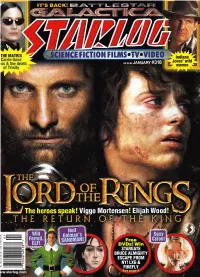

THE MATRIX SCIENCE FICTION FILMS*TV*VIDEO Indiana Carrie-Anne 4 Jones' wild iss & the death JANUARY #318 r women * of Trinity Exploit terrain to gain tactical advantages. 'Welcome to Middle-earth* The journey begins this fall. OFFICIAL GAME BASED OS ''HE I.l'l't'.RAKY WORKS Of J.R.R. 'I'OI.KIKN www.lordoftherings.com * f> Sunita ft* NUMBER 318 • JANUARY 2004 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE ^^^^ INSIDEiRicinE THISti 111* ISSUEicri ir 23 NEIL CAIMAN'S DREAMS The fantasist weaves new tales of endless nights 28 RICHARD DONNER SPEAKS i v iu tuuay jfck--- 32 FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY Creator is \ 1 *-^J^ Joss Whedon glad to see his saga out on DVD 36 INDY'S WOMEN L/UUUy ICLdll IMC dLLIUII 40 GALACTICA 2.0 Ron Moore defends his plans for the brand-new Battlestar 46 THE WARRIOR KING Heroic Viggo Mortensen fights to save Middle-Earth 50 FRODO LIVES Atop Mount Doom, Elijah Wood faces a final test 54 OF GOOD FELLOWSHIP Merry turns grim as Dominic Monaghan joins the Riders 58 THAT SEXY CYLON! Tricia Heifer is the model of mocmodern mini-series menace 62 LANDniun OFAC THETUE BEARDEAD Disney's new animated film is a Native-American fantasy 66 BEING & ELFISHNESS Launch into space As a young man, Will Ferrell warfare with the was raised by Elves—no, SCI Fl Channel's new really Battlestar Galactica (see page 40 & 58). 71 KEYMAKER UNLOCKED! Does Randall Duk Kim hold the key to the Matrix mysteries? 74 78 PAINTING CYBERWORLDS Production designer Paterson STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., Owen 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats.