My Commonplace Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Anthropology of Gender and Death in Corneille's Tragedies

AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF GENDER AND DEATH IN CORNEILLE’S TRAGEDIES by MICHELLE LESLIE BROWN (Under the Direction of Francis Assaf) ABSTRACT This study presents an analysis of the relationship between gender and death in Corneille’s tragedies. He uses death to show spectators gender-specific types of behavior to either imitate or reject according to the patriarchal code of ethics. A character who does not conform to his or her gender role as dictated by seventeenth-century society will ultimately be killed, be forced to commit suicide or cause the death of others. Likewise, when murderous tyrants refrain from killing, they are transformed into legitimate rulers. Corneille’s representation of the dominance of masculine values does not vary greatly from that of his contemporaries or his predecessors. However, unlike the other dramatists, he portrays women in much stronger roles than they usually do and generally places much more emphasis on the impact of politics on the decisions that his heroes and heroines must make. He is also innovative in his use of conflict between politics, love, family obligations, personal desires, and even loyalty to Christian duty. Characters must decide how they are to prioritize these values, and their choices should reflect their conformity to their gender role and, for men, their political position, and for females, their marital status. While men and women should both prioritize Christian duty above all else, since only men were in control of politics and the defense of the state, they should value civic duty before filial duty, and both of these before love. Since women have no legal right to political power, they are expected to value domestic interests above political ones. -

Winter 2018 Incoming President Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer and Say a Heartfelt Goodbye to Laurie Raymond

Autism Society of Maine 72 B Main St, Winthrop, ME 04364 Fall Autism INSIDE Call:Holiday 1-800-273-5200 Sale Holiday Crafts Conference Items can be seenPage 8 Page 6 and ordered from ASM’s online store: Page 5 www.asmonline.org Silicone Chew Necklaces *Includes Gift Box Folding Puzzle Tote Animals & Shapes- $9.00 Add 5.5% Sales Tax $16.00 Raindrops & Circles-$8.00 Let ME Keychain Keychain Silver Ribbon Silver Puzzle Keychain $5.00 $5.00 $10.00 $10.00 $6.00spread the word on Maine Lanyard AUTISM Stretchy Wristband Ceramic Mug $6.00 $4.00 $3.00 $11.00 Lapel Pin $5.00 Magnets Small $3.00 Large $5.00 Glass Charm Bracelet Glass Pendant Earrings 1 Charm Ribbon Earrings $10.00 $15.00 $8.00 $6.00 $6.00 Maine Autism Owl Charm Colored Heart Silver Beads Colored Beads Autism Charm Charm $3.00 $1.00 $1.00 $3.00 $3.00 Developmental Connections Milestones by Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer The Autism Society of Maine would like to introduce our Winter 2018 incoming President Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer and say a heartfelt goodbye to Laurie Raymond. representatives have pledged to Isn’t it wonderful that we are never too old to grow? I was make this a priority. worried about taking on this new role but Laurie Raymond kindly helped me to gradually take on responsibilities, Opportunities for secretary to VP, each change in its time. Because this is my first helping with some of our President’s corner message, of course I went to the internet to priorities for 2019 help with this important milestone. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

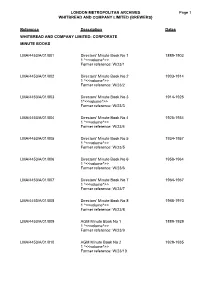

{BREWERS} LMA/4453 Page 1 Reference Description Dates

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 WHITBREAD AND COMPANY LIMITED {BREWERS} LMA/4453 Reference Description Dates WHITBREAD AND COMPANY LIMITED: CORPORATE MINUTE BOOKS LMA/4453/A/01/001 Directors' Minute Book No 1 1889-1903 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/1 LMA/4453/A/01/002 Directors' Minute Book No 2 1903-1914 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/2 LMA/4453/A/01/003 Directors' Minute Book No 3 1914-1925 1^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/3 LMA/4453/A/01/004 Directors' Minute Book No 4 1925-1934 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/4 LMA/4453/A/01/005 Directors' Minute Book No 5 1934-1957 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/5 LMA/4453/A/01/006 Directors' Minute Book No 6 1958-1964 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/6 LMA/4453/A/01/007 Directors' Minute Book No 7 1964-1967 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/7 LMA/4453/A/01/008 Directors' Minute Book No 8 1968-1970 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/8 LMA/4453/A/01/009 AGM Minute Book No 1 1889-1929 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/9 LMA/4453/A/01/010 AGM Minute Book No 2 1929-1935 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/10 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 WHITBREAD AND COMPANY LIMITED {BREWERS} LMA/4453 Reference Description Dates LMA/4453/A/01/011 Managing Directors' Committee Minute Book 1937-1939 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/11 LMA/4453/A/01/012 Board Papers 1945-1947 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/12 LMA/4453/A/01/013 Policy Meetings Minute Book 1946 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/13 LMA/4453/A/01/014 Policy Meetings Minute Book 1947 -

2004 Crosscut Literary Magazine

Cover Photo: “Rocks” by Kathy Wall wrapped from the front to the back cover. Crosscut literary magazine Husson College Bangor, Maine 2004 Volume Twelve i Crosscut EDITORIAL STAFF Editors Greg Winston Amanda Kitchen Cover Photo “Rocks” Kathy Wall Crosscut website: http://english.husson.edu/crosscut/ First Edition. Press run of 500 copies; no reprinting is planned. Printed by Fast Forms Printing & Paper, Bangor, Maine. Funded by Husson College. All rights to individual works are retained by their authors. For permission to reprint, contact the authors and artists directly. Address all correspondence and submissions (up to three poems, three drawings or photographs, or prose selections up to 5,000 words) to Editorial Staff, Crosscut magazine, Department of English, Husson College, One College Circle, Bangor, ME 04401. ii Preface The mere thought of spring brings to mind together- ness and renewal. Rivers of melting snow and ice form tributaries, finding each other and crossing paths, flow- ing together to free themselves from their stagnant form. The once-frozen paths weaving throughout our Maine woods shed their white armor, heartedly inviting pairs of treaded footprints to meet along their crossing journeys. Gloves and mittens are tossed in the closet for another year, allowing loved ones to entwine their hands into one another’s as they venture out into the fresh new season. Over the years, Crosscut has become a powerful symbol of spring in just this light. The poetry, prose, and imagery in each of its contributor’s art flows together, melting movement and life into the freshly printed pages. Its readers, in turn, breathe in each stir of emotion and new image formed, feeling renewed and refreshed. -

Horse-Breeding – Being the General Principles of Heredity

<i-. ^u^' Oi -dj^^^ LIBRARYW^OF CONGRESS. Shelf.i.S.g^. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. HORSE-BREEDING BKING THE GENERAL PRINCIPLES OE HEREDITY APPLIED TO The Business oe Breeding Horses, IXSTEUCTIOJS'S FOR THE ^IaNAGE^HKNT Stallions, Brood Mares and Young' Foals, SELECTION OF BREEDING STOCK. r y-/' J. H. SANDERS, rdiinrof 'Tlie Bleeder's Gazette," '-Breeders' Trotting Stuil Book," '•ri'r<lu Honorary member of the Chicago Eclectic Medical SoeieU>'flfti'r.> ^' Illinois Veterinary Medical Association, ^rl^.^^Ci'^'' ~*^- CHICAGO: ' ^^ J. H. SANDERS & CO. ]8S5. r w) <^ Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1885, BY J. H. SANDERS, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. ^ la TABLE OF CONTENTS. Preface 5 CHAPTER I. General Principles of Breeding.—General Laws of Heredity- Causes of Variation from Original Typos — Modifications from Changed Conditions of Life—Accidental Variations or " Sports "— Extent of Hereditary Inflaence—The Formation of Breeds—In-Breeding and Crossing—Value of Pedigree- Relative Size of Sire and Dam—Influenee of First Impregna- tion—Effect of Imagination on Color of Progeny—Effect of Change of Climate on the Generative Organs—Controlling the Sex 9 CHAPTER II. Breeds of Horses.— Thoroughbreds — Trotters and Roadsters — Orloffs or Russian Trotters—Cleveland Bays—Shire or Cart Horses—Clydesdales—Percherons-Otber Breeds (58 CHAPTER III. Stallions, Brood Mares and Foals.— Selection of Breeding- Stock—General Management of the StaUion—Controlling the Stallion When in Use—When Mares Should be Tried—The -

Mineral' Waters

If ; '¦ ¦ ¦ * ¦ ¦ :; ¦¦ ¦ • ; • -tti-j i i ; i- • ' ^"^^ ,Mi^; ; ¦ ¦ i^E rT!f H <?"> .v-r.i"',.' ":' i p^«^tB*^*is hj^i:ILtli ,ytiL ^ . iM i|u8 (fl - ^'«H rV t'V ^1; !\Aff3 5!rl¦ l .i¦ % ^ i TCHIS JOURNAL IN^1849. , - . s \ ' ; ! ¦ : 'fV ¦ ifi '^ fH' .f; fj ;? 1 : ' ¦ ' ¦ i V : M'i -! ^' ' . ^ ;- ; !. : ; j—M; r^l^ vvv ^^^ ¦ • ' " ' HO; - ' ' ¦ . SEOtETBiED AT ,THB ' ^ ' ¦ • GBBEBAI. - j ^ . ••; ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ • TP> |? T | *rOK-Wc^ 8f.li : ^' ¦]¦ , . /). ' * ; ' ' ¦• "- -— -¦ ¦ ¦ - . • • - —¦ ¦::.]. •;—|-....^w ¦ : ¦ , '- - tfSE T/ABSEPCinD XJET7D ¦:%=;• ( .-:- " I. ::::?. '», ¦*,.;• " .. , . .. » '!. .;? /. v > i ESTABLISHED—1847. i s j ' E:S7G<:3j;,ipii'3iilaa|oa .in Dou£h oi? Erclactl. 4. Purv^or s ' ' to ¦ H.EH ¦ ' • • : ani Ssooii&Elitumon SATTTRDAY . ./; Pallia?«3 nerv VTUDAT, . 'Ilorninft, o". Kii. ffl or^l'50, COcnatH-SirMt, ' ':' ; . • j j lopioaitn IKB PEOVIKOUI max.). ftEICE—OZW PEISJTiTeMly (in Ad\nr sa)J £:. {i ' . By . 3?6Bt'(Yetoly), 6s. M. J « 'x U'J' . Ji. ilrT3\!j -iu ij : j \'\ ^S • ond P. 0. ¦ 0?^T i.U Choqnisa Orders, modo p^Tatjb j : ' : f ' . " ' to COAIIKUUB P. EEBIIOKB, at this OSco, •; ¦ ¦ : 3 I v ' I ' i ¦ ? ¦ i .; ' : v itc^ r^ ! '¦; ¦ "" ¦ THE fcC3 .oiwmla^a , B2tondvcl 7 . cramrat th-} ; ^" " "; : : ¦ C_J )r i> ll^ p"rum is : iifii le, or u » i EOi-olmta, iraao ca and mrtiiUtar. ; scatty, farainu •——-' <—'V-A—^_J I ;.. J ">>_ > ¦ ¦ ' ¦ ¦' ' ' ' ' ' olotae. ,! &o., la¦• .Wattrford, fKiitmitvy/ Tipperory, I : ' 'i' i ¦::/ . ' ' ' ! ' tio eostir tf >Ireliiid^ cota:=13y. «=-Tli<i^Ni:WB ¦ : ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ and ! ' ¦ * ¦ " • • ->• '.:¦ •>¦ ¦ - . ; : ¦ ¦:¦ : - . • • . : ;' ' .:. , v >iV has at allied a cipralatiODnoyer eqaallodby any paper , f:. .. ;. ,i nubKstad in "Woterford, and i8 admittedly the load- ¦ US ]or real) n thin important city, with which thorci¦ ¦ o ¦ ¦ : daily oemiuunioatlon from London. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

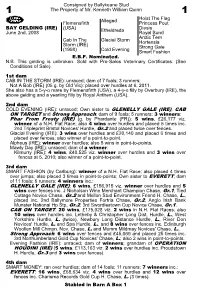

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Leading Efforts of Growth & Change in Medicine February 8-10Th, 2019

Midwinter Symposium 2019: Leading Efforts of Growth & Change in Medicine February 8-10th, 2019 Holiday Inn by the Bay, 88 Spring Street, Portland, ME 21.75 AOA Category 1-A CME credit (20.75 AAFP Prescribed credits expected) Topics Include: • Featuring Keynote Speakers: Plus Special Events: • Anti-Depressants • Ethical Dilemmas at End of Karen Nichols, D.O. • Mariner’s Hockey Games! Life • Lung Cancer Screenings “I’m the Doctor, So I’m in Charge • Silent Auction to Benefit Maine • OMT Billing & Coding • Opioid Use Disorder: Right?” Leadership Skills for Osteopathic Educational Update Supporting Recovery Physicians— Friday, Feb. 8th Foundation • Influenza Update • Youth Substance Use Frank Hubbell, D.O. • Research Forum for UNE COM • Obesity Treatment • Employment Contract Students & Residents “What You Need to Know Before Negotiations • Exploring food reactions You Go: Preparing for Medical • Free OMT Treatment Clinic • Interesting Cases in • Transgender 101 for the Mission Trips Around the World” Women's Health PCP • Exhibit Hall featuring vendors Saturday, Feb. 9th & special prize raffles • Toxicology • And Much More! Maine Osteopathic Association’s Public Information and Educational Committee Co-Chairs: Brian Kaufman, D.O. and Kiran Mangalam, D.O. 2019 Midwinter Symposium Draft Program Agenda* 21.75 AOA Category 1-A CME Credits Friday, February 8, 2019 Saturday, February 9, 2019 8.5 CME Credits 9.25 CME Credits 7:00- 8:00 am Breakfast Lecture: Lung Cancer 7:00- 8:00 am Breakfast Lecture: HPV Screenings Update Vaccinations for Adults -

HEADLINE NEWS • 7/27/07 • PAGE 2 of 7

STREET SENSE IN ‘DANDY’ BREEZE HEADLINE p7 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2007 SANFORD WON BY HIS SON FULL BOAT FOR WHITNEY He wasn=t quite as impressive as his sire, who won So competitive is Saturday=s GI Whitney H. that Brass the 1999 GII Sanford S. by nearly 10 lengths, but Jim Hat (Prized), a Grade I winner and good enough to Scatuorchio=s Ready=s Image (More Than Ready) was cross the line second in the world=s richest horse race in dominating enough, taking yesterday=s Saratoga feature 2006, is pegged at 20-1 on Eric Donovan=s morning by four convincing lengths line. A full field of 12 handicap horses has been assem- from Tale of Ekati (Tale of the bled for the $750,000 feature Cat). Wheeled back on 13 and, while trainer Kiaran days= rest off a debut victory McLaughlin was stripped of Apr. 20, Ready=s Image was his chance to win back-to- third as the 7-5 chalk in the back runnings with the retire- GIII Kentucky BC S. at Chur- ment of Invasor (Arg), he has chill May 3. The blinkers went a capable replacement with Ready’s Image on for the July 1 Tremont S. West Point Thoroughbred=s Adam Coglianese at Belmont and the dark bay Flashy Bull (Holy Bull). The charged home a 7 3/4-length four-year-old comes into the winner. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ...............................................................................................................................