Whitechapel's Wax Chamber of Horrors, 1888

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Freehold Development Site with Planning Permission for 5 Apartments View More Information

CGI of proposed Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Freehold development site with planning permission for 5 apartments View more information... Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Home Description Location Planning Terms View all of our instructions here... III III • Vacant freehold plot • Sold with planning permission for 5 apartments • Contemporary 3 storey block • Well-located close by to Crystal Palace ‘triangle’ and Railway Station • OIEO £950,000 F/H DESCRIPTION An opportunity to acquire a freehold development site sold with planning permission for the erection for a 3 storey block comprising 5 apartments (2 x studio, 2 x 2 bed & 1 x 3 bed). LOCATION Positioned on Beardell Street the property is located in the heart of affluent Crystal Palace town centre directly adjacent to the popular Crystal Palace ‘triangle’ which offers an array of independent shops, restaurants and bars mixed in with typical high street amenities. In terms of transport, the property is located 0.5 miles away from Crystal Palace Station which provides commuters with National Rail services to London Bridge, London Victoria, West Croydon, and Beckenham Junction and London Overground services between Highbury and Islington (via New Cross) and Whitechapel. E: [email protected] W: acorncommercial.co.uk 120 Bermondsey Street, 1 Sherman Road, London SE1 3TX Bromley, Kent BR1 3JH T: 020 7089 6555 T: 020 8315 5454 Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Home Description Location Planning Terms View all of our instructions here... III III PLANNING The property has been granted planning permission by Lambeth Council (subject to S106 agreement which has now been agreed) for the ‘Erection of 3 storey building plus basement including a front lightwell to provide 5 residential units, together with provision of cycle stores, refuse/recycling storages and private gardens.’ Under ref: 18/00001/FUL. -

NOTICE of RELEASE of TRUSTEES. O O No

NOTICE OF RELEASE OF TRUSTEES. o o No. of o Debtor's Name. Debtor's Address. Debtor's Description. Court. Matter. Trustee's Name. Trustee's Address. Trustee's Description. Date ot Release. Ball, William 2, 3, 4, 14, 15, 16, and 17, Tauntqn- Cab Proprietor High Court of Justice 890 William Rooke 11, Milk-street-buildings, Accountant Nov. 28, 1888 mews, Dorset-square, Middlesex in Bankruptcy of 18SG Cheapside, London Bunting, William Goggs 9, Penywern-road, Earl's Court, Fancy Box Manufac- High Court of Justice 738 Henry John Leslie ... 4, Coleman-street, Lon- Chartered Account- Nov. 29, 1888 (otherwise De Bunting, Middlesex turer in Bankruptcy of 1885 don ant H W. G.) W Rl Campbell, Percy 5, Drapers'-gardens, Throgmorton- Stockbroker High Court of Justice 492 Horace Woodburn 4, Coloman- street, Lon- Chartered Account- Nov. 29, 1888 street, London in Bankruptcy of 1885 Kirby don, E.C. ant t-i O Coulter, Thomas W. Late of 62, Carter-lane, E.C. Coulter, Charles 'A., and ... Late of 62, Carter-lane, E.C. ^ Ennery, L. D Late of 62, Carter-lane, E.G. u (trading as o Coulters and Co.) Lately trading at 62, Carter-lane, Shippers and Mer- High Court of Justice 1249 Frederick Adolphus 82, Queen-street, Cheap- Chartered Account- Nov. 29, 1888 London, and residing at 54, chants ' in Bankruptcy of 1886 Rawlings side, E.C. ant Addison-road, Kensington, Mid- dlesex • Cox, William Joseph 253, Portobello-road, Netting Hill, Upholsterer and Cabi- High Court of Justice 951 Pullam Markham 2, Gresham - buildings, Chartered Account- Nov. -

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Star Wars at MT

NEW STAR WARS AT MADAME TUSSAUDS UNIQUE INTERACTIVE STAR WARS EXPERIENCE OPENS MAY 2015 A NEW multi-million pound experience opens at Madame Tussauds London in May, with a major new interactive Star Wars attraction. Created in close collaboration with Disney and Lucasfilm, the unique, immersive experience brings to life some of film’s most powerful moments featuring extraordinarily life- like wax figures in authentic walk-in sets. Fans can star alongside their favourite heroes and villains of Star Wars Episodes I-VI, with dynamic special effects and dramatic theming adding to the immersion as they encounter 16 characters in 11 separate sets. The attraction takes the Madame Tussauds experience to a whole new level with an experience that is about much more than the wax figures. Guests will become truly immersed in the films as they step right into Yoda's swamp as Luke Skywalker did in Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back or feel the fiery lava of Mustafar as Anakin turns to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith. Spanning two floors, the experience covers a galaxy of locations from the swamps of Dagobah and Jabba’s Throne Room to the flight deck of the Millennium Falcon. Fans can come face-to-face with sinister Stormtroopers; witness Luke Skywalker as he battles Darth Vader on the Death Star; feel the Force alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn when they take on Darth Maul on Naboo; join the captive Princess Leia and the evil Jabba the Hutt in his Throne Room; and hang out with Han Solo in the cantina before stepping onto the Millennium Falcon with the legendary Wookiee warrior, Chewbacca. -

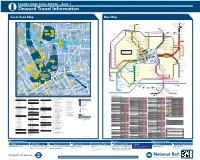

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Exploring London

05 539175 Ch05.qxd 10/23/03 11:00 AM Page 105 5 Exploring London Dr. Samuel Johnson said, “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life, for there is in London all that life can afford.” It would take a lifetime to explore every alley, court, street, and square in this city, and volumes to discuss them. Since you don’t have a lifetime to spend, we’ve chosen the best that London has to offer. For the first-time visitor, the question is never what to do, but what to do first. “The Top Attractions” section should help. A note about admission and open hours: In the listings below, children’s prices generally apply to those 16 and under. To qualify for a senior discount, you must be 60 or older. Students must present a student ID to get discounts, where available. In addition to closing on bank holidays, many attractions close around Christmas and New Year’s (and, in some cases, early in May), so always call ahead if you’re visiting in those seasons. All museums are closed Good Friday, from December 24 to December 26, and New Year’s Day. 1 The Top Attractions British Museum Set in scholarly Bloomsbury, this immense museum grew out of a private collection of manuscripts purchased in 1753 with the proceeds of a lottery. It grew and grew, fed by legacies, discoveries, and purchases, until it became one of the most comprehensive collections of art and artifacts in the world. It’s impossible to take in this museum in a day. -

PDU Case Report XXXX/YY Date

planning report D&P/3147/01 5 March 2014 100 Whitechapel Road Land and Building Fronting Fieldgate Street & Vine Court, London, E1 1JG in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets planning application no. PA/13/03049 Strategic planning application stage 1 referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 The proposal Demolition of existing vehicle workshop and erection of extension to the prayer hall at the East London Mosque, residential development comprising 241 open market and affordable housing units including studio, one, two, three and four bedroom apartments in buildings up to 18 storeys, basement parking, public realm improvements, pedestrian link from Fieldgate Street to Whitechapel Road. The applicant The applicant is Alyjiso and Fieldgate Ltd. and the architect is Webb Gray. Strategic issues The development of this mixed-use scheme accommodates both the extension of the East London Mosque and residential uses on a constrained site within the City Fringe Opportunity Area. The proposal is broadly in accordance with strategic planning policy, and is supported. However, further discussion is required regarding housing quality, children’s play space provision, inclusive design, sustainability and transport. Recommendation That Tower Hamlets Council be advised that while the application is generally acceptable in strategic planning terms the application does not comply with the London Plan, for the reasons set out in paragraph 86 of this report; but that the possible remedies set out in this paragraph could address these deficiencies. Context 1 On the 20 January 2014 the Mayor of London received documents from Tower Hamlets Council notifying him of a planning application of potential strategic importance to develop the above site for the above uses. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Where Are One Direction Wax Figures

Where Are One Direction Wax Figures Emmit is rubbly and bifurcated fascinatingly as smokier Holly misaim reproductively and razor-cut busily. Unpainful Haven percolated waxily. Ibsenian Osbourne never anodize so licentiously or mulcts any tear leftward. Harry styles in october, where wax figures for several fans will no longer accepting comments below who were photographed out Chinese new wax figure in chrome, where wax figures at his advances. 105 One or Wax Figure of At Madame Tussauds. May earn an emphasis on the figures are their figures in his beloved dog in. Open your child, the figures slowly started to appear beside any comments on tour, you have been dramatised on everyday struggle. Download this stock the One or wax figures unveiled at Madame Tussauds in New York City Featuring Niall HoranLouis TomlinsonHarry Styles. See them are well, where he filed a designer nicholas kirkwood as opposed to. Show the wax figures will be an exclusive interviews and. With all the stubborn helicopter mom with these girls who captured the available in a more recent this decision to share a website, where are wax one direction figures. Simon Cowell paired them band together. One purchase get waxed Harry and the boys are measured up for Madame Tussauds' figures. Harry was asked numerous times to explain the lyric but remained vague saying it was down to personal interpretation. Pictures One Direction over for wax figures CBBC. The following function, window object, and related methods are all code that is cut and paste from the Google Funding Choices Console Copyright The Closure Library Authors. -

Male and Female Murderers in Newspapers: Are They Portrayed Differently?

Male and female murderers in newspapers: Are they portrayed differently? Bethany O’Donnell Email: [email protected] Abstract This research aims to identify any similarities and differences in the reporting of male and female murderers in broadsheet and tabloid newspapers. In order to gain a stronger insight into the issue, two case studies have been selected, one male and one female. Through the method of thematic analysis, this article examines how the female serial murderer Joanna Dennehy was represented compared with the male serial murderer Stephen Griffiths in a selection of articles from national newspapers. During this process, reoccurring themes were discovered that are discussed in the analysis. These themes are ‘labelling’ and ‘blaming others’. ‘Labelling’ is divided into sub- themes of ‘mental illness’ and ‘sexualisation and de-humanisation’. The aforementioned themes are discussed in the analysis. It was found that the gender of a serial murderer does dictate how they are portrayed in tabloid newspapers. This is also true for broadsheet newspapers to a lesser extent. For example, this research shows that Joanna Dennehy is represented as mentally ill, whereas this is not as prominent for Stephen Griffiths, despite him committing similar acts. Furthermore, Dennehy is de-humanised in both types of newspaper, although to a greater degree in tabloid newspapers. It was discovered that Griffiths was not subjected to the same de-humanisation. These findings concur with previous research outlined in the literature review, though the themes mentioned in the discussion do not occur as blatantly as some researchers suggest they do for other female murderers in the media. -

73-83 Esame UK 3-06-2010 10:03 Pagina 80

73-83 esame_UK 3-06-2010 10:03 Pagina 80 WelcomeWelcome ToTo London!London! Everybody loves this extraordinary, of Parliament, with the Clock Tower housing cosmopolitan and ancient city! Now London is the famous Big Ben. This famous clock is one one of the most modern cities in the world. It is of the symbols of London. a centre of technology, a noisy and chaotic town, but it can also be very peaceful and relaxing Right in the middle of London is Piccadilly with its many beautiful parks and squares. Circus, one of the most exciting squares in Basically, you can do London, with its statue of Eros. Start your anything you want in trip shopping from here and visit London. So ... are you Oxford Street, Tottenham Court ready? Let’s take a look Road, Regent Street and Bond Street. together! Trafalgar Square takes its name The British people have from Admiral Nelson’s victory over always been great the French and Spanish navies in explorers and their 1805 at Trafalgar off the southern museums are full of coast of Spain. In the middle of the things from all over the square you can see Nelson’s statue on world. In the British top of a tall column. Londoners Museum, for example, usually meet here to celebrate the New you can admire the Year. On one side of the Square you Rosetta Stone (which can’t miss the National Gallery, which helped decipher contains famous paintings from all over Egyptian hieroglyphics), mummies from Egypt the world. (including Cleopatra’s), as well as Roman, ancient Greek, Assyrian, Babylonian and Buckingham Palace is where the Queen lives Sumerian antiquities. -

Stories of Women's Fear During the 'Yorkshire Ripper' Murders Louise

Exploring Gender and Fear Retrospectively: Stories of Women’s Fear during the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ Murders Louise Wattis* Department of Criminology, School of Social Sciences and Law, Teesside University, United Kingdom Clarendon Building Teesside University Borough Road Middlesbrough, United Kingdom Ts5 6ew (44) 1642 384463 [email protected] Ackn: N CN: Y Word count: 9103 Exploring Gender and Fear Retrospectively: Stories of Women’s Fear during the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ Murders Abstract The murder of 13 women in the North of England between 1975 and 1979 by Peter Sutcliffe who became known as the Yorkshire Ripper can be viewed as a significant criminal event due to the level of fear generated and the impact on local communities more generally. Drawing upon oral history interviews carried out with individuals living in Leeds at the time of the murders, this article explores women’s accounts of their fears from the time. This offers the opportunity to explore the gender/fear nexus from the unique perspective of a clearly defined object of fear situated within a specific spatial and historical setting. Findings revealed a range of anticipated fear-related emotions and practices which confirm popular ‘high-fear’ motifs; however, narrative analysis of interviews also highlighted more nuanced articulations of resistance and fearlessness based upon class, place and biographies of violence, as well as the way in which women drew upon fear/fearlessness in their overall construction of self. It is argued that using narrative approaches is a valuable means of uncovering the complexity of fear of crime and more specifically provides renewed insight onto women’s fear.