PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auction V Iewing

AN AUCTION OF Ancient Coins and Artefacts World Coins and Tokens Islamic Coins The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Monday 30 September 2013 10:00 Free Online Bidding Service AUCTION www.dnw.co.uk Monday 23 September to Thursday 26 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Strictly by appointment only Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 27, 28 and 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Monday 30 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale VIEWING Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or [email protected] Catalogued by Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley, Jim Brown, Tim Wilkes and Nigel Mills In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley or Jim Brown Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Session 1, 10.00 Ancient Coins from the Collection of Dr Paul Lewis.................................................................3001-3025 Ancient Coins from other properties ........................................................................................3026-3084 Ancient Coins – Lots ..................................................................................................................3085-3108 Artefacts ......................................................................................................................................3109-3124 10-minute intermission prior to Session 2 World Coins and Tokens from the Collection formed by Allan -

Coins and Medals;

CATALOGUE OF A VERY IKTERESTIKG COLLECTION'' OF U N I T E D S T A T E S A N D F O R E I G N C O I N S A N D M E D A L S ; L ALSO, A SMx^LL COLLECTION OF ^JMCIEjMT-^(^REEK AND l^OMAN foiJMg; T H E C A B I N E T O F LYMAN WILDER, ESQ., OF HOOSICK FALLS, N. Y., T O B E S O L D A T A U C T I O N B Y MJSSSBS. BAjYGS . CO., AT THEIR NEW SALESROOMS, A/'os. yjg and ^4.1 Broadway, New York, ON Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, May 21, 23 and 2Ji,, 1879, AT HALF PAST TWO O'CLOCK. C a t a l o g u e b y J o l a n W . H a s e l t i n e . PHILADELPHIA: Bavis & Phnnypackeh, Steam Powee Printers, No. 33 S. Tenth St. 1879. j I I I ih 11 lii 111 ill ill 111 111 111 111 11 1 i 1 1 M 1 1 1 t1 1 1 1 1 1 - Ar - i 1 - 1 2 - I J 2 0 - ' a 4 - - a a 3 2 3 B ' 4 - J - 4 - + . i a ! ! ? . s c c n 1 ) 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 'r r '1' '1' ,|l l|l 1 l-Tp- S t ' A L E O P O n e - S i x t e e n t h o f a n I n c h . -

Auction V Iewing

AN AUCTION OF World and Islamic Coins The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Thursday 13 June 2013 14:00 Free Online Bidding Service www.dnw.co.uk AUCTION Monday 20 May to Friday 7 June inclusive 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Strictly by appointment only A limited view will also take place at the London Coin Fair, Holiday Inn, Coram Street, London WC1, on Saturday 1 June Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, 10, 11 and 12 June 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Thursday 13 June 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of each day’s Sale Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or [email protected] VIEWING Catalogued by Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley, Jim Brown and Tim Wilkes In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley or Jim Brown Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS This auction will be conducted in one session, commencing at 14.00 World Coins.................................................................................................................................1201-1465 World Coins – Lots .....................................................................................................................1466-1554 Islamic Coins ...............................................................................................................................1555-1590 For British Coins, lots 1-1196, see separate catalogue INVESTMENT GOLD The symbol G adjacent to a lot -

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined An Analysis ofthe Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies F. A. HAYEK Nohel Laureate 1974 Diseases desperate grown, By desperate appliances are reli'ved, Or not at all. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (Hamlet, Act iv, Scene iii) THIRD EDITION ~~ Published by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1990 First published in October 1976 Second Edition, revised and enlarged, February 1978 Third Edition, with a new Introduction, October 1990 by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 2 Lord North Street, Westminster, London SWIP 3LB © THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1976, 1978, 1990 Hobart Paper (Special) 70 All rights reseroed ISSN 0073-2818 ISBN 0-255 36239-0 Printed in Great Britain by GORON PRO-PRINT CO LTD 6 Marlborough Road, Churchill Industrial Estate, Lancing, W Sussex Text set in 'Monotype' Baskeroille CONTENTS Page PREFACE Arthur Seldon 9 PREFACE TO THE SECOND (EXTENDED) EDITION A.S. 11 AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION 13 A NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION 16 THE AUTHOR 18 INTRODUCTION TO THE THIRD EDITION Geoffrey E. Wood 19 THE PRACTICAL PROPOSAL 23 Free trade in money 23 Proposal more practicable than utopian European currency 23 Free trade in banking 24 Preventing government from concealing depreciation 25 II THE GENERALISATION OF THR UNDERLYING PRINCIPLE 26 Competition in currency not discussed by economists 26 Initial advantages of government monopoly in money 27 III THE ORIGIN OF THE GOVERNMENT PREROGATIVE OF MAKING MONEY 28 Government certificate of metal weight and purity 29 The appearance of paper money 31 -

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars Lecture Set #34 Project of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club Photographed by John Cork & Raymond Reingohl Introduction Trade Dollars in this presentation are grouped into 3 categories • True Trade Dollars • It was intended to circulate in remote areas from its minting source • Accepted Trade Dollars • Trade dollar’s value was highly accepted for trading purposes in distant lands • Examples are the Spanish & Mexican 8 Reales and the Maria Theresa Thaler • Controversial Trade Dollars • A generally accepted dollar but mainly minted to circulate in a nation’s colonies • Examples are the Piastre de Commerce and Neu Guinea 5 Marks This is the Schlick Guldengroschen, commonly known as the Joachimstaler because of the large silver deposits found in Bohemia; now in the Czech Republic. The reverse of the prior two coins. Elizabeth I authorized this Crown This British piece created to be used by the East India Company is nicknamed the “Porticullis Crown” because of the iron grating which protected castles from unauthorized entry. Obverse and Reverse of a Low Countries (Netherlands) silver Patagon, also called an “Albertus Taler.” Crown of the United Amsterdam Company 8 reales issued in 1601 to facilitate trade between the Dutch and the rest of Europe. Crown of the United Company of Zeeland, minted at Middleburg in 1602, similar in size to the 8 reales. This Crown is rare and counterfeits have been discovered to deceive the unwary. The Dutch Leeuwendaalder was minted for nearly a century and began as the common trade coin from a combination of all the Dutch companies which fought each other as well as other European powers. -

False ? Model.Combipageviewmodel

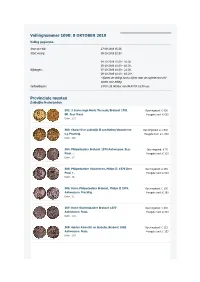

Veilingnummer 1090: 8 OKTOBER 2019 Veiling gegevens Start pre-bid: 27-08-2019 05:26 Start veiling: 08-10-2019 22:50 04-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. 05-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. Kijkdagen: 07-10-2019 10:00 - 21:00. 08-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00*. *tijdens de veiling kunt u kijken naar de objecten tot 100 kavels voor afslag. Ophaaldagen: 14 t/m 18 oktober van 09.00 tot 16.00 uur. Provinciale munten Zuidelijke Nederlanden 502: 2 Souvereign Maria Theresia/Brabant 1761 Openingsbod: € 500 BR. Zeer Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 600 Delm. 215. 503: Chaise D'or Lodewijk II van Malen/Vlaanderen Openingsbod: € 1.500 z.j. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 1.500 Delm. 466. 504: Philipsdaalder Brabant 1574 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 70 Fraai -. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 17. 505: Philipsdaalder Vlaanderen, Philips II. 1575 Zeer Openingsbod: € 150 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 500 Delm. 36. 506: Halve Philipsdaalder Brabant, Philips II 1574, Openingsbod: € 100 Antwerpen. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 180 Delm. 51. 507: Halve Statendaalder Brabant 1577 Openingsbod: € 200 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 200 Delm. 118. 508: Gulden Albrecht en Isabella, Brabant 1602 Openingsbod: € 125 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 155 Delm. 235. 509: Patagon Philips IV, Brabant 1664 Brussel. Zeer Openingsbod: € 90 Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 150 Delm. 285. 510: Halve dukaton Philips IV, Brabant 1638 Openingsbod: € 100 Brussel. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 289. 511: Dukaton Maria Theresia 1754 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 80 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 130 Delm. 375. 512: Halve Dukaton Maria Theresia 1750 Openingsbod: € 50 Antwerpen. Zeer Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 85 Delm. 379. 513: Kronenthaler Franz I 1765 B. -

HARMONY Or HARMONEY

Niklot Kluessendorf Harmony in money – one money for one country ICOMON e-Proceedings (Shanghai, 2010) 4 (2012), pp. 1-5 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org Harmony in money – one money for one country Niklot Klüßendorf Amöneburg, Germany [email protected] This paper discusses the German reforms from 1871 to 1876 for 26 States with different monetary traditions. Particular attention is paid to the strategy of compromise that produced harmony, notwithstanding the different traditions, habits and attitudes to money. Almost everybody found something in the new system that was familiar. The reform included three separate legal elements: coinage, government paper money and banknotes, and was carried out in such a way to avoid upsetting the different parties. Under the common roof of the new monetary unit, traditional and regional elements were preserved, eg in coin denominations, design, and even in the colours of banknotes. The ideas of compromise were helpful to the mental acceptance of the new money. As money and its tradition are rooted in the habits and feelings of the people, the strategy of creating harmony has to be taken into consideration for many monetary reforms. So the German reforms were a good example for the euro that was introduced with a similar spirit for harmony among the participating nations. New currencies need intensive preparation covering political, economic and technical aspects, and even psychological planning. The introduction of the euro was an outstanding example of this. The compromise between national and supranational ideas played an important role during the creation of a single currency for Europe. Euro banknotes, issued by the European Central Bank, demonstrate the supranational idea. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521632277 - The Logic of Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond Walter Mattli Excerpt More information 1 Introduction 1 The phenomenon of regional integration Regional integration schemes have multiplied in the past few years and the importance of regional groups in trade, money, and politics is increasing dramatically. Regional integration, however, is no new phenomenon. Examples of StaatenbuÈnde, Bundesstaaten, Eidgenossen- schaften, leagues, commonwealths, unions, associations, pacts, confed- eracies, councils and their like are spread throughout history. Many were established for defensive purposes, and not all of them were based on voluntaryassent. This book looks at a particular set of regional integration schemes. The analysis covers cases that involve the voluntary linking in the economic and political domains of two or more formerly independent states to the extent that authorityover keyareas of national policyis shifted towards the supranational level. The ®rst major voluntaryregional integration initiatives appeared in the nineteenth century. In 1828, for example, Prussia established a customs union with Hesse-Darmstadt. This was followed successively bythe Bavaria WuÈrttemberg Customs Union, the Middle German Commercial Union, the German Zollverein, the North German Tax Union, the German MonetaryUnion, and ®nallythe German Reich. This wave of integration spilled over into what was to become Switzer- land when an integrated Swiss market and political union were created in 1848. It also brought economic and political union to Italyin the risorgimento movement. Integration fever again struck Europe in the last decade of the nineteenth century, when numerous and now long- forgotten projects for European integration were concocted. In France, Count Paul de Leusse advocated the establishment of a customs union in agriculture between Germanyand France, with a common tariff bureau in Frankfurt.1 Other countries considered for membership were Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Spain. -

German States

Modern Dime Size Silver Coins of the World GERMAN STATES ====================================================================== ====================================================================== BADEN, GRAND DUCHY of, (GERMANY) KARLSRUHE MINT FOOTNOTE: The Peace of Vienna , following an armistice be- ====================================================================== tween Austria and Italy, was proclaimed on October 3, 1866 which 3 KREUZER 18MM .350 FINE 1.232 GRAMS surrendered Venetia to Italy. A confederation of North German ====================================================================== States, with Prussia at it's head, was established; and Bavaria, Wurtemberg, Baden,and Hesse-Darmstadt became independent 1866 240,000 sovereign states. Universal History, Israel Smith Clarke, Phila., 1867 390,000 1881. 1868 315,000 1869 285,000 ====================================================================== 1870 259,000 PRUSSIA, KINGDOM of, (GERMANY) 1871 u/m BERLIN MINT ====================================================================== ¿OV: Arms of Baden, / SCHEIDE MUNZE (token 1 SILBER GROSCHEN 18MM .220 FINE 2.196 GRAMS money) below. ====================================================================== ¿RV: 3 / KREUZER / DATE within wreath of oak tied 1841 u/m with ribbon below. 1842 u/m 1943 u/m EDGE: Plain 1844 u/m 1845 u/m MINT: (no mintmark) = KARLSRUHE 1846 u/m 1847 u/m REFERENCE: C-150 1848 u/m 1849 u/m POPULATION: Baden Grand Duchy - 1892 - 1,500,000 1850 u/m with capital Karlsruhe with 62,000 inhabitants. 1851 -

Foreign Files/1700 TABLES.Pdf

A series of currency reforms took place between the late 1600s (Spain), between 1702-1717 (England) and 1709 Holy Roman Empire (Germany and Austria). We can use these contemporary sources to calculate coin values in terms of Spanish dollars at the British standard value of 4s/6d or 54d. This works out to $4.44 to a pound. Later, when the US began minting its own dollars, the British considered them equal to the Spanish. ENGLAND DOLLARS HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE DOLLARS SECONDARY SOURCE The ratios of pence to In 1978, John J. dollars and pence to McCusker published A Spanish Dollar In 1709 a currency reform convention was held kreutzers determines the values of a In 1702 [except as noted], Sir Isaac was officially worth in Nuremberg, and published in "Cambio the approx. value of number of coins, Newton calculated the value of gold 54d, its silver Mercatorio" by Georg Heinrich Paritio. kreutzers to dollars. based on Newton, coins at the "Goldsmith's value" of £4 content verified by Silver value, not Variations are due to bank exchange rates (960d) per troy oz. (31.1 grams) rather Newton as 53.88d. A Thaler coin was 1/9 Koln-Marck of silver, about Newton's actual silver value and other primary than the British "standard value" of exchange rate, at (See below.) At that 99¢ based on the average prices in London during vs the German standard sources. £3.19s.8!d 4£ sterling per oz rate 1d = 1.85¢ these years, given by McCusker. exchange rate. S. D. McCusker (given in Pence (d) to Dollars Official value at Kreutzer to Dollars hundredths of a GOLD MONIES — UNWORN. -

Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and Currencies in History from Earliest Times to the Euro

E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 3 Money Museum Drachm, Dirham, Thaler, Pound Money and currencies in history from earliest times to the euro Coins and maps from the MoneyMuseum with texts by Ursula Kampmann E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 4 All rights reserved Any form of reprint as well as the reproduction in television, radio, film, sound or picture storage media and the storage and dissemination in electronic media or use for talks, including extracts, are only permissible with the approval of the publisher. 1st edition ??? 2010 © MoneyMuseum by Sunflower Foundation Verena-Conzett-Strasse 7 P O Box 9628 C H-8036 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 242 76 54, Fax: +41 (0)44 242 76 86 Available for free at MoneyMuseum Hadlaubstrasse 106 C H-8006 Zürich Phone: +41 (0)44 350 73 80, Bureau +41 (0)44 242 76 54 For further information, please go to www.moneymuseum.com and to the Media page of www.sunflower.ch Cover and coin images by MoneyMuseum Coin images p. 56 above: Ph. Grierson, Münzen des Mittelalters (1976); p. 44 and 48 above: M. J. Price, Monnaies du Monde Entier (1983); p. 44 below: Staatliche Münzsammlung München, Vom Taler zum Dollar (1986); p. 56 below: Seaby, C oins of England and the United Kingdom (1998); p. 57: archive Deutsche Bundesbank; p. 60 above: H. Rittmann, Moderne Münzen (1974) Maps by Dagmar Pommerening, Berlin Typeset and produced by O esch Verlag, Zürich Printed and bound by ? Printed in G ermany E_Drachm_maps_korr_1_64_Drachme_Dirhem 01.09.10 11:19 Seite 5 Contents The Publisher’s Foreword . -

View PDF Catalogue

adustroaliawn conin auctieiosns AUCTION 336 This auction has NO room participation. Live bidding online at: auctions.downies.com AUCTION DATES Monday 18th May 2020 Commencing 9am Tuesday 19th May 2020 Commencing 9am Wednesday 20th May 2020 Commencing 9am Thursday 21st May 2020 Commencing 9am Important Information... Mail bidders Mail Prices realised All absentee bids (mail, fax, email) bids must Downies ACA A provisional Prices Realised list be received in this office by1pm, Friday, PO Box 3131 for Auction 336 will be available at 15th May 2020. We cannot guarantee the Nunawading Vic 3131 www.downies.com/auctions from execution of bids received after this time. Australia noon Friday 22nd May. Invoices and/or goods will be shipped as soon Telephone +61 (0) 3 8677 8800 as practicable after the auction. Delivery of lots Fax +61 (0) 3 8677 8899 will be subject to the receipt of cleared funds. Email [email protected] Website www.downies.com/auctions Bid online: auctions.downies.com 1 WELCOME TO SALE 336 Welcome to Downies Australian Coin Auctions Sale 336! As with so many businesses, and the Australian community in general, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented Downies with many challenges – specifically, in preparing Sale 336. The health and safety of our employees and our clients is paramount, and we have worked very hard to both safeguard the welfare of all and create an auction of which we can be proud. As a consequence, we have had to make unprecedented modifications to the way Sale 336 will be run. For example, the sale will be held without room participation.