A Female Demon of Turkic Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Autonomy and Conflict in Republics of Russia and Ukraine

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Communist and Post-Communist Studies 41 (2008) 79e91 www.elsevier.com/locate/postcomstud Identity, autonomy and conflict in republics of Russia and Ukraine Karina V. Korostelina Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University, 3330 N. Washington Blvd., Truland Building, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22201, United States Available online 19 February 2008 Abstract This paper discusses the results of the survey conducted in co-operation with the European Research Center for Migration and Ethnic Relations, concerning identity in the Autonomous Republics of Russia and Ukraine. The survey queried 6522 residents of such republics as Bash- kortostan, Karelia, Komi, Sakha (Yakutia), and Tatarstan in Russia, and Crimea in Ukraine. It examined the construction of social identities, common narratives regarding threats and deprivations, confidence in public institutions, the prevalence of views toward national minor- ities as ‘fifth columns’, ethnic stereotypes, ethnocentrism, and other conflict indicators. An early warning model, built on the basis of the results, measured the potential for conflict based on these factors, and found that it was most pronounced in Bashkortostan and Crimea, and to a lesser extent in Tatarstan. Conflict was less likely in Sakha, Karelia, and Komi, although there were still certain indicators that suggested potential problems, including moderate support for independence in these republics. Ó 2008 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The Regents of the University of California. Keywords: Russia; Ukraine; Ethnic; National; Regional and religious identity; Autonomy; Conflict; Stereotypes; Threat; Trust; Deprivation; Ethnic minorities Introduction Since the fall of the USSR, several Autonomous Republics of the Russian Feder- ation have been seeking increased autonomy from Moscow. -

The Vocabulary of Inanimate Nature As a Part of Turkic-Mongolian Language Commonness

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 6 S2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy November 2015 The Vocabulary of Inanimate Nature as a Part of Turkic-Mongolian Language Commonness Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor, Department of the Kalmyk language and Mongolian studies Director of the Mongolian and Altaistic research Scientific centre, Kalmyk State University 358000, Republic of Kalmykia, Elista, Pushkin street, 11 Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n6s2p126 Abstract The article deals with the problem of commonness of Turkic and Mongolian languages in the area of vocabulary; a layer of vocabulary, reflecting the inanimate nature, is subject to thorough analysis. This thematic group studies the rubrics, devoted to landscape vocabulary, different soil types, water bodies, atmospheric phenomena, celestial sphere. The material, mainly from Khalkha-Mongolian and Old Written Mongolian languages is subject to the analysis; the data from Buryat and Kalmyk languages were also included, as they were presented in these languages. The Buryat material was mainly closer to the Khalkha-Mongolian one. For comparison, the material, mainly from the Old Turkic language, showing the presence of similar words, was included; it testified about the so-called Turkic-Mongolian lexical commonness. The analysis of inner forms of these revealed common lexemes in the majority of cases allowed determining their Turkic origin, proved by wide occurrence of these lexemes in Turkic languages and Turkologists' acknowledgement of their Turkic origin. The presence of great quantity of common vocabulary, which origin is determined as Turkic, testifies about repeated ancient contacts of Mongolian and Turkic languages, taking place in historical retrospective, resulting in hybridization of Mongolian vocabulary. -

On the Influence of Turkic Languages on Kalmyk Vocabulary

Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 6; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education On the Influence of Turkic Languages on Kalmyk Vocabulary Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin1 & Svetlana Menkenovna Trofimova1 1 Kalmyk state University, Department of Russian language and General linguistics, Elista, Republic of Kalmykia, Russian Federation Correspondence: Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin, Kalmyk state University, Department of Russian language and General linguistics, Pushkin street, 11, Elista, 358000, Republic of Kalmykia, Russian Federation. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 30, 2014 Accepted: December 1, 2014 Online Published: February 25, 2015 doi:10.5539/ass.v11n6p192 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n6p192 Abstract The article covers the development and enrichment of vocabulary in the Kalmyk language and its dialects influenced by Turkic languages from ancient times when there were a hypothetical so called Altaic linguistic community in the period of general Mongolian linguistic condition and general Oirat condition. After Kalmyks moved to Volga, they already had an independent Kalmyk language. The research showed how the Kalmyk language was influenced by the ancient Turkic language, the Uigur language and the Kirghiz language, and also by the Kazakh language and the Nogai language (the Qypchaq group). Keywords: Kalmyk language vocabulary, vocabulary development, Altaic linguistic community, general Mongolian vocabulary, ancient Turkic loanwords, general Kalmyk vocabulary, Turkic loanwords in Derbet dialect, Turkic loanwords in Torgut dialect, Turkic loanwords in the Sart-Kalmyk language 1. Introduction As it is known, Turkic and Mongolian languages together with Tungus-Manchurian languages have long been considered kindred and united into one so called group of “Altaic languages”. -

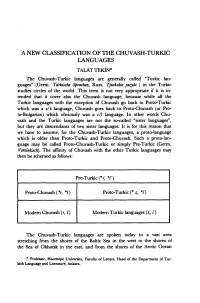

A New Classification of the Chuvash-Turkic Languages

A NEW CLASSİFICATİON OF THE CHUVASH-TURKIC LANGUAGES T A L Â T TEKİN * The Chuvash-Turkic languages are generally called “Turkic lan guages” (Germ. Türkische Sprachen, Russ. Tjurkskie jazyki ) in the Turkic studies circles of the world. This term is not very appropriate if it is in- tended that it cover also the Chuvash language, because while ali the Turkic languages with the exception of Chuvash go back to Proto-Turkic vvhich was a z/s language, Chuvash goes back to Proto-Chuvash (or Pro- to-Bulgarian) vvhich obviously was a r/l language. In other vvords Chu vash and the Turkic languages are not the so-called “sister languages”, but they are descendants of two sister languages. It is for this reason that we have to assume, for the Chuvash-Turkic languages, a proto-language vvhich is older than Proto-Turkic and Proto-Chuvash. Such a proto-lan- guage may be called Proto-Chuvash-Turkic or simply Pre-Turkic (Germ. Vortürkisch). The affinity of Chuvash vvith the other Turkic languages may then be schemed as follovvs: Pre-Turkic i*r, * i ) Proto-Chuvash ( *r, */) Proto-Turkic (* z, *s) Modem Chuvash (r, l) Modem Turkic languages (z, s ) The Chuvash-Turkic languages are spoken today in a vast area stretching from the shores of the Baltic Sea in the vvest to the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk in the east, and from the shores of the Arctic Ocean * Professor, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Letters, Head of the Department of Tur- kish Language and Literatüre, Ankara. ■30 TALÂT TEKİN in the north to the shores of Persian Gulf in the south. -

The Imposition of Translated Equivalents to Avoid T

International Humanities Studies Vol. 3 No.1; March 2016 ISSN 2311-7796 On some future tense participles in modern Turkic languages Aynel Enver Meshadiyeva Abstract This paper investigates phonetic and morphological-semantic features and the main functions of the future participle –ası/-esi in modern Turkic languages. At the present time, a series of questions concerning an etymology of the future participle –ası/-esi in the modern Turkic languages does not have a due and exhaustive treatment in the Turkology. In the course of the research, similar and distinctive features of the future participles –ası/-esi in Turkic languages were revealed. It should be noted that comparative-historical researches of the grammatical elements in the modern Turkic languages have gained a considerable scientific meaning and undoubted actuality. The actuality of the paper’s theme is conditioned by these factors. Keywords: Future tense participle –ası/-esi, comparative-historical analysis, etimology, oghuz group, kipchak group, Turkic languages, similar and distinctive features. Introduction This article is devoted to comparative historical analysis of the future tense participle –ası/- esi in modern Turkic languages. The purpose of this article is to study a comparative historical analysis of the future tense participle –ası/-esi in Turkic languages. It also aims to identify various characteristic phonetic, morphological, and syntactic features in modern Turkic languages. This article also analyses materials of different dialects of Turkic languages, and their old written monuments. The results of the detailed etymological analysis of the future tense participle –ası/-esi help to reveal the peculiarities of lexical-semantic and morphological structure of the Turkic languages’ participle. -

De-Demonising the Old Testament

De-Demonising the Old Testament An Investigation of Azazel , Lilith , Deber , Qeteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible Judit M. Blair Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2008 Declaration I declare that the present thesis has been composed by me, that it represents my own research, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. ______________________ Judit M. Blair ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank and acknowledge for their support and help over the past years. Firstly I would like to thank the School of Divinity for the scholarship and the opportunity they provided me in being able to do this PhD. I would like to thank my ‘numerous’ supervisors who have given of their time, energy and knowledge in making this thesis possible: To Professor Hans Barstad for his patience, advice and guiding hand, in particular for his ‘adopting’ me as his own. For his understanding and help with German I am most grateful. To Dr Peter Hayman for giving of his own time to help me in learning Hebrew, then accepting me to study for a PhD, and in particular for his attention to detail. To Professor Nick Wyatt who supervised my Masters and PhD before his retirement for his advice and support. I would also like to thank the staff at New College Library for their assistance at all times, and Dr Jessie Paterson and Bronwen Currie for computer support. My fellow colleagues have provided feedback and helpful criticism and I would especially like to thank all members of HOTS-lite I have known over the years. -

How Much Land Does a Man Need? by Leo Tolstoy

Lesson Ideas English Language Arts 6-12 How much land does a man need? By Leo Tolstoy How much land does a man need? is a short story written by Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910). In the story, Tolstoy reflects critically on the hierarchy of 19th century Russian society where the poor were deprived and the rich stayed wealthy. Personal belongings, property, and other forms of material wealth were measures of an individual’s worth and determined social class. Land shortage was a major issue in 19th century Russia, and in his story, Tolstoy associates the Devil with the main character’s greed for land. How much land does a man need? inspires discussion about the concepts of how greed and both socio-economic inequalities and injustices can contribute to our desire to “have more,” even if it means taking risks. The story also calls into question additional topics that students can apply to their own lives such as how we anticipate and justify the consequences of our actions when fueled by greed or other motivations. Many of these themes serve a double purpose as they are also relevant to building gambling literacy and competencies. After all, being able to identify our own tendencies toward greed can help us pause and perhaps rethink our decisions. And being mindful that we are more than our wealth can release us of the burden of comparing our and others’ financial value. Pahom sets out to encircle so much land that by the Brief summary afternoon he realizes he has created too big of a circuit. -

Life Science Journal 2014;11(7S) Http

Life Science Journal 2014;11(7s) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Some results of the research system-synchronous modern dialect of the Tatar language Ferits Yusupovich Yusupov and Irina Sovetovna Karabulatova Kazan Federal University, Tatarstan str, 2, Kazan, 420021, Russian Federation Abstract. This article analyzes the study of modern dialects of the Tatar language. The authors were carried out dialectological expeditions over the years of various regions of residing Tatars. The authors have drawn parallels with the different groups of Turkic languages. The specific layer is highlighted in the diasystem, which we nominally call as oguzizms. They belong to archaism category and have the anachronistic character. Their presence in all specific systems shows that these forms were frequently used, but later they were superseded by “rival” forms. It seems probable that these forms were derived from old-Kipchak language. Nowadays they are considered as the old-Turkic layer of origins. The authors provide new classification parameters to allocate Tatar dialects. [Yusupov F.Y., Karabulatova I.S. Some results of the research system-synchronous modern dialect of the Tatar language Life Sci J 2014;11(7s):246-] (ISSN:1097-8135). http://www.lifesciencesite.com. 50 Keywords: Turkology, Tatar language, modern dialect, Classificatory features of dialects, verb Introduction the formation of infinitive forms from archaic action Researchers are studying the Turkic nouns (as uku faydaly / reading is useful) and languages from different positions. However, the main participles. The formation of participles became line of research is based on the ethnography of complicated by means of additional morphological speaking and contrastive linguistics. The first is features as a result of grammatical designation of directed represented widely in the American studies. -

Uralic Studies, Languages, and Researchers

Uralic studies, languages, and researchers Edited by Sándor Szeverényi Studia uralo-altaica 54 Redigunt: Katalin Sipőcz András Róna-Tas István Zimonyi Uralic studies, languages, and researchers Proceedings of the 5th Mikola Conference 19–20, September 2019 Edited by Sándor Szeverényi Szeged, 2021 © University of Szeged, Department of Altaic Studies, Department of Finno-Ugrian Philology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the author or the publisher. Printed in 2021. Printed by: Innovariant Ltd., H-6750 Algyő, Ipartelep 4. ISBN 978-963-306-803-8 (printed) ISBN 978-963-306-804-5 (pdf) ISSN 0133-4239 (Print) ISSN 2677-1268 (Online) Table of contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................... 9 Sándor Szeverényi Notes on Nicolaes Witsen and his Noord en Oost Tartarye ...................................... 11 Rogier Blokland Undiscovered treasures: From the field research archive to the digital database ...... 27 Beáta Wagner-Nagy, Chris Lasse Däbritz, and Timm Lehmberg On the language use of the first Finnish medical text .............................................. 45 Meri Juhos Sajnovics, the responsible fieldworker ..................................................................... 55 Sándor Szeverényi The life and work of the Saami theologian and linguist: Anders Porsanger ............ 71 Ivett Kelemen The use and semantics of the Northern Mansi diminutive -riś~rəś .......................... 81 Bernadett Bíró The event of “giving” and “getting” in Siberian Uralic languages ........................... 99 Katalin Sipőcz A word-formational approach to neologisms in modern Northern Mansi .............. 119 Susanna Virtanen Word and stem repetitions in the heroic epic songs collected by Antal Reguly .... -

9783956501845 Ebook.Pdf

Groups, Ideologies and Discourses: Glimpses of the Turkic Speaking World © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul ISTANBULER TEXTE UND STUDIEN HERAUSGEGEBEN VOM ORIENT-INSTITUT ISTANBUL BAND 10 © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul Groups, Ideologies and Discourses: Glimpses of the Turkic Speaking World edited by Christoph Herzog Barbara Pusch WÜRZBURG 2016 ERGON VERLAG WÜRZBURG IN KOMMISSION © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul Umschlaggestaltung: Taline Yozgatian Foto: Barbara Pusch Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISBN 978-3-95650-184-5 ISSN 1863-9461 © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul (Max Weber Stiftung) Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung des Werkes außerhalb des Urheberrechtsgesetzes bedarf der Zustimmung des Orient-Instituts Istanbul. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen jeder Art, Übersetzungen, Mikro- verfilmung sowie für die Einspeicherung in elektronische Systeme. Gedruckt mit Unter- stützung des Orient-Instituts Istanbul, gegründet von der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, aus Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und -

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Edited by Susan Baddeley Anja Voeste De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 ThisISBN work 978-3-11-021808-4 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, ase-ISBN of February (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 LibraryISSN 0179-0986 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ae-ISSN CIP catalog 0179-3256 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-028812-4 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-028817-9 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- fie;This detaillierte work is licensed bibliografische under the DatenCreative sind Commons im Internet Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs über 3.0 License, Libraryhttp://dnb.dnb.deas of February of Congress 23, 2017.abrufbar. -

First Report on the Russian Federation

CRI (99) 3 European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance First report on the Russian Federation Adopted on 26 January 1999 For further information about the work of the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) and about the other activities of the Council of Europe in this field, please contact: Secretariat of ECRI Directorate General of Human Rights – DG II Council of Europe F - 67075 STRASBOURG Cedex Tel.: +33 (0) 3 88 41 29 64 Fax: +33 (0) 3 88 41 39 87 E-mail: [email protected] Visit our web site: www.coe.int/ecri 2 INTRODUCTION The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) was set up in 1994, at the instigation of the first Summit meeting of Heads of State and Government of the member States of Council of Europe, to combat the growing problems of racism, xenophobia, anti- Semitism and intolerance threatening human rights and democratic values in Europe. The members of ECRI were chosen for their recognised expertise in questions relating to racism and intolerance. The task given to ECRI was to: review member States' legislation, policies and other measures to combat racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and intolerance and their effectiveness; propose further action at local, national and European level; formulate general policy recommendations to member States; and to study international legal instruments applicable in the matter with a view to their reinforcement where appropriate. One aspect of the activities developed by ECRI to fulfil its terms of reference is its country-by- country approach, which involves carrying out an analysis of the situation in each of the member States in order to provide governments with helpful and concrete proposals.