J. I. Packer by Alister Mcgrath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Document Including the Annual Financial Report

REFERENCE DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2012 PROFILE LAGARDÈRE, A WORLD-CLASS PURE-PLAY MEDIA GROUP LED BY ARNAUD LAGARDÈRE, OPERATES IN AROUND 30 COUNTRIES AND IS STRUCTURED AROUND FOUR DISTINCT, COMPLEMENTARY DIVISIONS: • Lagardère Publishing: Book and e-Publishing; • Lagardère Active: Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage; • Lagardère Services: Travel Retail and Distribution; • Lagardère Unlimited: Sport Industry and Entertainment. EXE LOGO L'Identité / Le Logo Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins Echelle: d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. Agence d'architecture intérieure LAGARDERE - Concept C5 - O’CLOCK Optimisation Les entrepreneurs devront s’engager à executer les travaux selon les règles de l’art et dans le respect des règlementations en vigueur. Ce 15, rue Colbert 78000 Versailles Date : 13 01 2010 dessin est la propriété de : VERSIONS - 15, rue Colbert - 78000 Versailles. Ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation. tél : 01 30 97 03 03 fax : 01 30 97 03 00 e.mail : [email protected] PANTONE 382C PANTONE PANTONE 382C PANTONE Informer, Rassurer, Partager PROCESS BLACK C PROCESS BLACK C Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la Echelle: Agence d'architecture intérieure solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. -

THE MENTOR 79, July 1993

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #79 ARTICLES: 8 - THE BIG BOOM by Don Boyd 40 - WHAT IS SF FOR by Sean Williams COLUMNISTS: 14 - NORTHERN FEN by Pavel A Viaznikov 17 - A SHORT HISTORY OF RUSSIAN "FANTASTICA" by Andrei Lubenski 32 - SWORDSMAN OF THE SHEPHERD'S STAR by Andrew Darlington 45 - IN DEPTH #6 by Bill Congreve COMIC SECTION: 20 - THE INITIATE Part 2 by Steve Carter DEPARTMENTS; 2 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 49 - THE R&R DEPT - Reader's letters 61 - CURRENT BOOK RELEASES by Ron Clarke FICTION: 4 - PREY FOR THE PREY by B. J. Stevens 23 - THE BROOKLYN BLUES by Brent Lillie Cover Illustration by Steve Carter. Internal Illos: Steve Fox p. 7, 39 Peggy Ranson p.11, 13, 44, 48 Sheryl Birkhead p. 49 Rod Williams p. 68 Julie Vaix p. 68 THE MENTOR 79, July 1993. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. Mail Address: THE MENTOR, c/- 34 Tower St, Revesby, NSW 2212, Australia. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions, if over 5 pages, preferred to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD) otherwise typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE anyway, for my comments. -

John-Murray-Translation-Rights-List

RIGHTS TEAM John Murray Press Rebecca Folland Rights Director - HHJQ Translation Rights List - Autumn 2019 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6288 NON-FICTION General Non-Fiction 7 Joanna Kaliszewska Head of Rights - John Murray Press Current Affairs, History & Politics 8 Deputy Rights Director - HHJQ [email protected] Popular Science 18 +44 (0) 20 3122 6927 Popular/Commercial Non-Fiction 25 Hannah Geranio Senior Rights Executive - HHJQ Travel 27 [email protected] Recent Highlights 31 FICTION Nick Ash Literary Fiction Rights Assistant - HHJQ 37 [email protected] General Fiction 47 Crime & Thriller 48 Hena Bryan Rights Assistant - JMP & H&S Recent Highlights 52 [email protected] JOHN MURRAY PRESS For nearly a quarter of a millennium, John Murray has been unashamedly populist, publishing the absorbing, SUBAGENTS provocative, commercial and exciting. Albania, Bulgaria & Macedonia Anthea Agency [email protected] Seven generations of John Murrays fostered genius and found readers in vast numbers, until in 2002 the firm be- Brazil Riff Agency [email protected] came a division of Hachette, under the umbrella of Hodder & Stoughton. China and Taiwan Peony Literary Agency marysia@peonyliterary agency.com IMPRINTS Czech Republic & Slovakia Kristin Olson Agency [email protected] At John Murray, we only publish books that take us by sur- prise. Classic authors of today who were mavericks of their Greece OA Literary Agency time – Austen, Darwin, Byron – were first published and [email protected] championed by John Murray. And that sensibility continues today. Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia Katai and Bolza Literary Agency [email protected] (Hungary) Two Roads publish about 15 books a year, voice-driven [email protected] (Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia) fiction and non-fiction – all great stories told with heart and intelligence. -

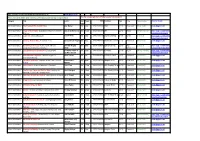

Titles Available to Order from Philip Garside Pubishing Ltd. Books

Titles available to order from Philip Garside Pubishing Ltd. [email protected] Prices and time to deliver were correct as at 19 January 2021 but may change in future This list is Copyright 2021 of Philip Garside Publishing Ltd Category Title Author Item Pages ISBN Publisher Year Price Time to deliver Click for details type Advent & Christmas The Shepherd Who Couldn't Sing Alan Barker Pbk 32pp 9780281076741 SPCK (2018) Please ask [Please Ask] [email protected] Advent & Christmas Image of the Invisible: Daily Bible readings from Advent to Amy Scott Robinson Pbk 160pp 9780857467898 BRF (2019) $32.00 [Allow 3-4 weeks] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthly Epiphany -selections/advent-and- Advent & Christmas Expectant: Advent Meditations Anne E Kitch Pbk 65pp 9781640651463 Church Publishing (2019) $23.50 [1 in stock] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthlychristmas-2019/ -selections/advent-and- Advent & Christmas Home by Another Way: A Christmas Story Barbara Brown Taylor Hbk 40pp 9781947888005 Westminster John Knox(2018) Please ask [Please Ask] [email protected]/ Advent & Christmas Something new to say: Words of spirit, faith and Bronwyn Angela Pbk 68pp 9780473398583 Spirit & Faith, NZ (2018) Was [2 in stock] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthly celebration for Advent and Christmas White $25.00, now -selections/pre-christmas- Advent & Christmas Daily Devotions for Advent 2019 (Living Gospel) Carmelite Sisters of Pbk 64pp 9781594719370 Ave Maria (2019) $12.00 [Allow 2-3 weeks] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthlysale-2019/ the Most Sacred -selections/advent-and- Advent & Christmas Dreamers and Stargazers: Creative Liturgies for ChrisHeart ofThorpe Los Angeles Pbk 240 9781848259713 Canterbury Press (2017) Please ask [Please Ask] [email protected]/ Incarnational Worship Advent & Christmas The Gift of New Hope: Scriptures for the Church Seasons Christopher L. -

Lagardère SCA, Un Groupe Industriel Atypique

École doctorale Erasme Laboratoire des Sciences de l’information et de la communication (LabSic, EA 1803) Doctorat Sciences de l’information et de la communication Le groupe LAGARDERE face aux mutations des industries de la culture et de la communication Michel DIARD Thèse dirigée par M. Philippe BOUQUILLION Soutenue publiquement le 30 janvier 2015 Membres du jury : Mme Dominique CARTELLIER, Université Stendhal – Grenoble 3 M. Bertrand LEGENDRE, Université Paris 13 M. Juan Carlos MIGUEL de BUSTOS, Université du Pays Basque, Bilbao (Espagne) M. Pierre MOEGLIN, Université Paris 13 M. Laurent PETIT, Université Paris 4 (ESPE) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! « J’ai laissé plus de choses à dire que je n’en ai dites (…) peut-être la prolixité et l’adulation ne seront pas au nombre des défauts qu’on pourra me reprocher. » ! Denis DIDEROT, Encyclopédie ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! à Marie-France et Jean-Michel ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 ! ! ! Remerciements ! ! ! Je remercie mon directeur Philippe BOUQUILLION pour ses conseils avisés, sa disponibilité et sa patience envers le doctorant aussi peu conventionnel que je fus. Je tiens aussi à associer à ces remerciements Pierre MOEGLIN et Yolande COMBES, qui, à chacune des séances du ‘’petit séminaire’’ du LabSic, m’ont permis d’approfondir mes questionnements à propos des industries culturelles. J’associerai à ces remerciements le directeur Du LabSic et du Labex ICCA, Bertrand LEGENDRE, pour m’avoir accueilli et invité à participer à l’université d’été du Labex ICCA me permettant de mieux appréhender le travail de recherche en sciences humaines. Merci aussi à tous les doctorants du LabSic pour les discussions passionnantes au sein du « petit séminaire ». Enfin, un grand merci à Marie-France, mon épouse, pour son soutien infaillible et sa très grande patience. -

Titles Available to Order from Philip Garside Pubishing Ltd. Books

Titles available to order from Philip Garside Pubishing Ltd. [email protected] Prices and time to deliver were correct as at 17 July 2021, but may change in future This list is Copyright 2021 of Philip Garside Publishing Ltd Item Category Title Author type PagesISBN Publisher Year Price Time to deliver Click for details Advent & Christmas The Shepherd Who Couldn't Sing Alan Barker Pbk 32pp 9780281076741 SPCK (2018) Please ask [Please Ask] [email protected] Advent & Christmas Image of the Invisible: Daily Bible readings from Advent to Epiphany Amy Scott Robinson Pbk 160pp 9780857467898 BRF (2019) $32.00 [Allow 3-4 weeks] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthly- selections/advent-and-christmas- Advent & Christmas Expectant: Advent Meditations Anne E Kitch Pbk 65pp 9781640651463 Church (2019) $23.50 [1 in stock] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthly- Publishing selections/advent-and-christmas- Advent & Christmas Home by Another Way: A Christmas Story Barbara Brown Taylor Hbk 40pp 9781947888005 Westminster (2018) Please ask [Please Ask] [email protected] John Knox Advent & Christmas Something new to say: Words of spirit, faith and celebration for Advent and Bronwyn Angela White Pbk 68pp 9780473398583 Spirit & Faith, (2018) Was [2 in stock] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthly- Christmas NZ $25.00, now selections/pre-christmas-sale-2019/ Advent & Christmas Daily Devotions for Advent 2019 (Living Gospel) Carmelite Sisters of the Most Pbk 64pp 9781594719370 Ave Maria (2019) $12.00$12.00 [Allow 2-3 weeks] https://pgpl.co.nz/monthly- Sacred Heart of Los Angeles selections/advent-and-christmas- Advent & Christmas Dreamers and Stargazers: Creative Liturgies for Incarnational Worship Chris Thorpe Pbk 240 9781848259713 Canterbury (2017) Please ask [Please Ask] [email protected] Press Advent & Christmas The Gift of New Hope: Scriptures for the Church Seasons Year C Christopher L. -

Hodder-Faith-Rights-Guide-Autumn-2020.Pdf

RIGHTS TEAM Rebecca Folland Rights Director - HHJQ [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6288 Joanna Kaliszewska Head of Rights - John Murray Press Deputy Rights Director - HHJQ [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6927 Hena Bryan Rights Assistant - Hodder & Stoughton, Headline, John Murray Press, Quercus [email protected] SUBAGENTS Albania, Bulgaria & Macedonia Anthea Agency [email protected] Brazil Riff Agency [email protected] China and Taiwan Peony Literary Agency marysia@peonyliterary agency.com Czech Republic & Slovakia Kristin Olson Agency [email protected] Germany Thomas Schlueck GmbH [email protected] Greece OA Literary Agency [email protected] Holland and Scandinavia Sebes [email protected] Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia Katai and Bolza Literary Agency [email protected] (Hungary) [email protected] (Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia) Indonesia Maxima Creative Agency [email protected] Japan Japan Uni [email protected] Korea Rmaeng2 [email protected] Spain and Portugal Julio F-Yanez Agencia Literaria [email protected] Poland Book/lab [email protected] Romania Simona Kessler International [email protected] Thailand and Vietnam The Grayhawk Agency [email protected] Turkey AnatoliaLit Agency [email protected] HODDER FAITH Hodder & Stoughton was founded in 1868 as a Christian publisher. Today the imprint Hodder Faith is one of the UK’s leading Christian publishers, with a list including the NIV Bible and a wide range of Christian books. Hodder Faith Rights List Autumn 2020 CONTENTS Childrens’ 6 Gift Books 9 Non-Fiction 11 Core List 40 Alpha Publishing 43 Fiction 49 5 Childrens’ SOUL FUEL FOR YOUNG EXPLORERS by Bear Grylls Inspiration for children and young people from adventurer Bear Grylls, brilliantly illustrated throughout. -

John Murray Press Translation Rights List

1 John Murray Press CONTACTS Translation Rights List - Spring 2019 Rebecca Folland Rights Director - HHJQ [email protected] FICTION +44 (0) 20 3122 6288 Literary Fiction 4 Joanna Kaliszewska Deputy Rights Director - HHJQ Head of Rights - John Murray Press General Fiction 8 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6927 Crime & Thriller 12 Grace McCrum Rights Manager Recent Highlights - Fiction 15 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6237 NON-FICTION Amy Hawkins Senior Rights Executive [email protected] Current Affairs, History & Politics 18 +44 (0) 20 3122 6684 MBS & Self-Help Hannah Geranio 26 Rights Executive [email protected] Popular Science 31 +44 (0) 20 3122 6137 Nick Ash Business & Coaching 36 Rights Assistant [email protected] Travel 40 Faith 42 Recent Highlights - Non-Fiction 50 2 3 Literary Fiction Literary Fiction THE AUNT WHO WOULDN’T DIE NOBBER Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay Oisín Fagan ‘A chaotic, furious, extraordinary Bengali confection A wildly inventive and audacious debut novel from ... Irresistible’ Philip Hensher, The Spectator Books of the author of Hostages the Year An ambitious noble and his three serving men At eighteen, Somlata married into the Mitras: a travel through the Irish countryside in the stifling once noble Bengali household whose descendants summer of 1348, using the advantage of the have taken to pawning off the family gold to keep plague which has collapsed society to buy up up appearances. When Pishima, the embittered large swathes of property and land. They come matriarch, dies, Somlata is the first to discover her upon Nobber, a tiny town, whose only living aunt-in-law’s body - and her sharp-tongued ghost. -

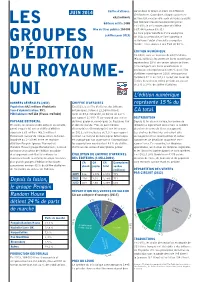

Les Groupes D'édition Au Royaume-Uni

Éditeurs actifs : Évolution du CA (en millions de £) OCTOBRE 2019 2 235 (2018) 3743 3613 3603 Chiffre d’affaires : 3387 3352 CA total LES 3,6 milliards £ (2018) Nombre de titres publiés : 206 386 (2017) 3118 CA 2976 2950 2736 2756 livre papier GROUPES 616 631 637 625 653 CA numérique ebooks + audiobooks 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 D’ÉDITION AU Source : The Publisher Association, 2019 SYSTÈME DE PRIX Le livre ne bénéficie plus depuis 1995 du système du prix unique. Le prix des livres ROYAUME-UNI se fixe donc librement. Chaque couverture de livre fait néanmoins état d’un prix de vente conseillé par l’éditeur, souvent peu respecté par PAYSAGE ÉDITORIAL CA par secteur éditorial 1 % les chaînes de librairies et grandes surfaces. En 2018, 2 235 maisons d’édition sont 7 % 16 % Amazon pratique aussi une politique de prix assujetties à la TVA. Le monde éditorial agressive, avec des réductions pouvant aller % britannique est marqué par une forte 9 de languesMéthodes jusqu’à 50 % du prix conseillé. polarisation : un très grand nombre de petites Scolaire Autre Les livres papier sont exemptés de TVA ; maisons côtoient quelques grands groupes Fiction ce n’est pas le cas des livres audio et transnationaux qui trustent le marché. % numériques soumis au taux de TVA général 0 1 Jeunesse de 20 %. Alors que de nombreux pays de l’UE profitent du récent changement de législation Non-Fiction 2 Penguin Random House, 6 européenne d’abaissement du taux de TVA sur % les publications numériques, le Royaume-Uni, Hachette UK, toujours en plein débat sur le Brexit, maintient le statu quo sur la TVA appliquée aux livres Académique / HarperCollins et professionnel numériques. -

HHJMQ Permission Request Form 1

HHJMQ Permission Request Form 1 Please complete this form, if you require permission for use of material from Hodder & Stoughton, Hodder Faith (including Bible text), Chambers, Teach Yourself (all titles), John Murray Press (including JM Learning), Headline Publishing Group, Quercus. APPLICANT DETAILS Applicant name* Company* Address* Invoice Address* (if different from above) Phone* Email* Today’s Date* REQUESTED MATERIAL Please check the cover, spine, and copyright page of the book. We are not in possession of file copies of all our books, and thus are unable to check this material on your behalf. Title of the book* Author/Editor* Publisher/Imprint* ISBN* (we categorically cannot process your request without this information) Publication date and Edition* HHJMQ Permission Request Form 2 WORD/LINE COUNT* FROM REQUESTED MATERIAL Number of words (prose only)* Line count (poetry/prayer only)* Page Reference* For recipes, please include name, and page number* Bible text Please check permitted free use limits here before applying for (please supply word and Bible text verse count for Bible text) https://www.hodder.co.uk/Information/Contact%20Us.page: Bible text continued * ( ) NIV Please delete as appropriate ( ) Today’s NIV ( ) NIRV Any other information which may help identify the material PROPOSED WORK IN WHICH THE EXTRACT IS TO BE USED (YOUR PUBLICATION) Your Publication Title* Your Author/Editor* Your Publisher* Formal permission is not required until you have secured a publisher Your territory for ( ) Throughout the World Distribution* -

Les Groupes D'édition Au Royaume-Uni

Chiffre d’affaires : varier dans le temps et entre les différents JUIN 2014 distributeurs. Cependant, chaque couverture € 4,2 milliards de livre fait mention d’un prix de vente conseillé LES Éditeurs actifs : 2 080 par l’éditeur (recommended retail price). En 2013, le prix moyen observé s’élève Nbe de titres publiés : 184 000 à £7,44 (environ €9,31). Le livre papier bénéficie d’une exemption (chiffres pour 2013) de TVA. En revanche, le livre numérique groupes ne fait pas l’objet d’une telle exemption fiscale : il est soumis à une TVA de 20 %. ÉDITION NUMÉRIQue En 2013, avec un montant de £509 millions D’ÉDITION (€636 millions), les ventes de livres numériques représentent 15 % des ventes totales de livres. Si la catégorie des livres académiques et professionnels représentaient 85 % du chiffre d’affaires numérique en 2009, cette part est AU roYAUME- tombée à 42 % en 2013. La part des livres de fiction, durant cette même période, est passée de 3 % à 39 % du chiffre d’affaires. UNI L’édition numérique DONNÉES GÉNÉRALES (2013) CHIffre d’affAIRES représente 15 % du Population : 64,1 millions d’habitants En 2013, le chiffre d’affaires des éditeurs Taux d’alphabétisation : 99 % britanniques s’élève à £3,389 milliards CA total. PIB / habitant : €27 110 (France : €27 860) (près de €4,2 milliards), en baisse de 2,2 % par rapport à 2012. Il correspond aux ventes DISTRIBUTION PAYSAGE ÉDITORIAL de livres papier et numériques au Royaume-Uni Depuis la fin du prix unique, le nombre de En 2013, on recense 2 080 éditeurs en activité, et dans le monde. -

Babelia (1991-2011)

UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA DEPARTAMENTO DE PERIODISMO II ! ANÁLISIS ESTRUCTURAL DE LA INTENCIONALIDAD DEL MENSAJE EN LOS SUPLEMENTOS CULTURALES: BABELIA (1991-2011) TESIS DOCTORAL Lda. Nuria Muñoz Fernández Directores: Catedrático Ramón Reig Dra. Antonia I. Nogales Bocio Sevilla, 2017 Análisis estructural de la intencionalidad del mensaje en los suplementos culturales: Babelia (1991-2011) Doctoranda: Lda. Nuria Muñoz Fernández Directores: Catedrático Ramón Reig. Dra. Antonia Isabel Nogales Bocio Programa de Doctorado: El Periodismo en el Contexto de la Sociedad Departamento de Periodismo II, Facultad de Comunicación Sevilla, abril de 2017 ANÁLISIS ESTRUCTURAL DE LA INTENCIONALIDAD DEL MENSAJE EN LOS SUPLEMENTOS CULTURALES: BABELIA (1991-2011) Agradecimientos El camino hasta estas páginas no ha sido fácil, muchas han sido las horas de trabajo y muchas las personas que me han acompañado en la andadura. En primer lugar, mi agradecimiento es para Ramón Reig, uno de mis directores y el pilar fundamental de esta investigación. Desde que llegué por casualidad a las páginas de sus libros, cuando aún ni presagiaba que la vida lo pondría en mi camino, mi admiración hacia su trabajo ha sido profunda y fruto de ello es la investigación que se presenta aquí, gracias por formar parte de ella. A Antonia Isabel Nogales, a Toñi, mi directora, por sumarse al camino con tanta ilusión y por estar ahí siempre, gracias. A Ladecom, por ser una ilusión en este largo camino, por ser una fuente de inspiración y un espacio de trabajo y amistad. Y a todos los ladecomitas que desde la clandestinidad hacen posible el espíritu Ladecom. Mi agradecimiento más especial es para todas las personas que de cerca han hecho posible llegar al final, a los que están y que siempre estarán y sobre todo a los que ya no están, por ser la fuerza que hace posible el caminar.