Mortality Rates in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating Disorders a Meta-Analysis of 36 Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

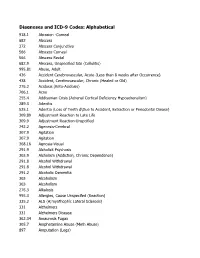

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings. -

Dsm-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders Anorexia Nervosa

DSM-5 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR EATING DISORDERS ANOREXIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA To be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa according to the DSM-5, the following criteria must be met: 1. Restriction of energy intaKe relative to requirements leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. 2. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. 3. Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight. Even if all the DSM-5 criteria for anorexia are not met, a serious eating disorder can still be present. Atypical anorexia includes those individuals who meet the criteria for anorexia but who are not underweight despite significant weight loss. Research studies have not found a difference in the medical and psychological impacts of anorexia and atypical anorexia. BULIMIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA According to the DSM-5, the official diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa are: • Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: o Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances. o A sense of lacK of control over eating during the episode (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). -

Patients' and Carers' Perspectives of Psychopharmacological

Chapter Patients’ and Carers’ Perspectives of Psychopharmacological Interventions Targeting Anorexia Nervosa Symptoms Amabel Dessain, Jessica Bentley, Janet Treasure, Ulrike Schmidt and Hubertus Himmerich Abstract In clinical practice, patients with anorexia nervosa (AN), their carers and clini- cians often disagree about psychopharmacological treatment. We developed two corresponding questionnaires to survey the perspectives of patients with AN and their carers on psychopharmacological treatment. These questionnaires were dis- tributed to 36 patients and 37 carers as a quality improvement project on a specialist unit for eating disorders at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Although most patients did not believe that medication could help with AN, the majority thought that medication for AN should help with anxiety (61.1%), con- centration (52.8%), sleep problems (52.8%) and anorexic thoughts (55.6%). Most of the carers shared the view that drug treatment for AN should help with anxiety (54%) and anorexic thoughts (64.8%). Most patients had concerns about potential weight gain, increased appetite, changes in body shape and metabolism during psychopharmacological treatment. By contrast, the majority of carers were not concerned about these specific side effects. Some of the concerns expressed by the patients seem to be AN-related. However, their desire for help with anxiety and anorexic thoughts, which is shared by their carers, should be taken seriously by clinicians when choosing a medication or planning psychopharmacological studies. Keywords: anorexia nervosa, psychopharmacological treatment, treatment effects, side effects, opinion survey, patients, carers 1. Introduction 1.1 Anorexia nervosa Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an eating disorder. According to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1], its diagnostic criteria are significantly low body weight, intense fear of weight gain, and disturbed body perception. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Eating Disorder Consultant Psychiatrist Job Description for CR174 Revision

Eating Disorder Consultant Psychiatrist Job Description for CR174 Revision Introduction Eating Disorders (ED) are a group of very complex Psychiatric Disorders and include Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorders and Atypical Eating Disorders. The complexity of these disorders can be gauged from the fact that at 12 months only fifty percent of adolescents with anorexia nervosa go in remission and only 40 % of patients with bulimia nervosa go in remission by six months, with relapse common. Research indicates childhood onset of ED carries a high risk of continuity in adulthood. Hospitalisation of patients with ED appears to be associated with worse prognosis; the number of patients with eating disorders who needed hospitalisation has doubled in last three years. More than six out of every ten people with ED suffer from other psychiatric co-morbidities such as depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). People with ED carry the highest risk of mortality among all the psychiatric disorders because of significant level of medical complexities associated with restriction of food intake. Patients with ED also carry higher risks of self-harm and suicide. People with Eating Disorders display a distorted attitude towards eating, weight and shape and may have irrational fear of becoming fat. The treatment of Eating disorders involves offering the patients individual and family based therapies, management of their physical and psychiatric risks and offering them nutritional support. The Consultant Psychiatrists with their comprehensive Psychiatric, Medical and Psychological training offer clinical leadership to Eating Disorder Services teams to deliver high quality care to patients who suffer from Eating Disorders and have very complex needs. -

Crosswalk Dsm-Iv – Dsm V – Icd-10 6.29.1

CROSSWALK DSM-IV – DSM V – ICD-10 6.29.1 DSM IV DSM IV DSM-IV Description DSM 5 Classification DSM- 5 CODE/ DSM-5 Description Classification CODE ICD 10 CODE Schizophrenia 297.1 Delusional Disorder Schizophrenia F22 Delusional Disorder 298.8 Brief Psychotic Disorder Spectrum and Other F23 Brief Psychotic Disorder 295.4 Schizophreniform Disorder Psychotic Disorders F20.81 Schizophreniform Disorder 295.xx Schizophrenia F20.9 Schizophrenia (DSM IV had different subtypes) 295.7 Schizoaffective Disorder F25.x Schizoaffective Disorder F25.0 Bipolar type F25.1 Depressive type 293.xx Psychotic Disorder Due To F06.X Psychotic Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition .81 With delusions F06.2 With delusions .82 With hallucinations F06.0 With hallucinations 293.89 Catatonic Disorder Due to . F06.1 Catatonia Associated with Another Mental . (was classified as Mental Disorder Disorders Due to a General F06.1 Catatonic Disorder Due to Another Medical Medical Condition No Condition Elsewhere Classified) F06.1 Unspecified Catatonia ___.___ Substance-Induced ___.___ Substance/Medications-Induced Psychotic _ Psychotic Disorder Disorder 29809 Psychotic Disorder NOS F28 Other Specified Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder F29 Unspecified Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder 297.3 Shared Psychotic Disorder Removed in DSM5 1 CROSSWALK DSM-IV – DSM V – ICD-10 6.29.1 DSM IV DSM IV DSM-IV Description DSM 5 Classification DSM- 5 CODE/ DSM-5 Description Classification CODE ICD 10 CODE Bipolar and 296.xx Bipolar I Disorder Bipolar and -

Eating Disorders Association (NEDA)

HealthPartners Care Coordination Clinical Care Planning and Resource Guide EATING DISORDER The following evidence‐based guideline was used in developing this clinical care guide: National Institute of Health (NIH‐ National Institute of Mental Health) and the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA). Documented Health Condition: Eating Disorder, Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Binge‐eating disorder, other What is an Eating Disorder? There is a commonly held view that eating disorders are a lifestyle choice. Eating disorders are actually serious and often fatal illnesses that cause severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may also signal an eating disorder. Common Causes of Eating Disorder Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors. Researchers are using the latest technology and science to better understand eating disorders. One approach involves the study of human genes. Eating disorders run in families. Researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Brain imaging studies are also providing a better understanding of eating disorders. For example, researchers have found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women. Diagnosis and Clinical Indicators Signs and Symptoms Anorexia Nervosa People with anorexia nervosa may see themselves as overweight, even when they are dangerously underweight. People with anorexia nervosa typically weigh themselves repeatedly, severely restrict the amount of food they eat, and eat very small quantities of only certain foods. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. -

Eating Disorders

658 Conferences and Reviews Eating Disorders A Review and Update ELLEN HALLER, MD, San Francisco, Califomia Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are prevalent illnesses affecting between 10/o and 100% ofadolescent and college age women. Developmental, family dynamic, and biologic factors are all important in the cause of this disorder. Anorexia nervosa is diagnosed when a person refuses to maintain his or her body weight over a minimal normal weight for age and height, such as 15% below that expected, has an intense fear of gaining weight, has a disturbed body image, and, in women, has primary or secondary amenorrhea. A diagnosis of bulimia nervosa is made when a person has recurrent episodes of binge eating, a feeling of lack of control over behavior during binges, regular use of self-induced vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, strict dieting, or vigorous exercise to prevent weight gain, a minimum of 2 binge episodes a week for at least 3 months, and persistent overconcern with body shape and weight. Patients with eating disorders are usually secretive and often come to the attention of physicians only at the insistence of others. Practitioners also should be alert for medical complications including hypothermia, edema, hypotension, bradycardia, infertility, and osteoporosis in patients with anorexia nervosa and fluid or electrolyte imbalance, hyperamylasemia, gastritis, esophagitis, gastric dilation, edema, dental erosion, swollen parotid glands, and gingivitis in patients with bulimia nervosa. Treatment involves combining individual, behavioral, group, and family therapy with, possibly, psychopharmaceuti- cals. Primary care professionals are frequently the first to evaluate these patients, and their encouragement and support may help patients accept treatment. -

Conceptualization of Anorexia Nervosa : a Theoretical Synthesis of Self-Psychology and Family Systems Perspectives

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2014 Conceptualization of anorexia nervosa : a theoretical synthesis of self-psychology and family systems perspectives Molly E. Gray Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gray, Molly E., "Conceptualization of anorexia nervosa : a theoretical synthesis of self-psychology and family systems perspectives" (2014). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/797 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Molly Gray Conceptualization of Anorexia Nervosa: A Theoretical Synthesis of Self-Psychology and Family Systems Perspectives ABSTRACT Anorexia nervosa is a life-threatening psychiatric disorder that has increased in diagnostic prevalence over the last century. Findings suggest that individuals at greatest risk are females between the ages of 15-22, who demonstrate heightened levels of perfectionism and a need for control. This theoretical thesis hopes to provide clinical social workers and other mental health professionals with a deeper understanding of the psychological, familial, and developmental factors contributing to the onset of the disorder in order to increase the effectiveness of future treatment. Self-psychology will be examined to offer a possible developmental and psychological framework for understanding the emotional challenges and distorted thought processes of the anorexic patient. Bowen's adaptation of family systems theory will be used to support the resilience and strength of the patient’s family unit by uncovering and addressing dysfunctional patterns.