Conceptualization of Anorexia Nervosa : a Theoretical Synthesis of Self-Psychology and Family Systems Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Concept of Self-Creativity Through the Validation of a New Survey Measure Alexandra Danae Varela Duquesne University

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 1-1-2017 Exploring the Concept of Self-Creativity Through the Validation of a New Survey Measure Alexandra Danae Varela Duquesne University Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Counselor Education Commons Recommended Citation Varela, A. D. (2017). Exploring the Concept of Self-Creativity Through the Validation of a New Survey Measure (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/199 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE CONCEPT OF SELF-CREATIVITY THROUGH THE VALIDATION OF A NEW SURVEY MEASURE A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Education Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Alexandra D. Varela December 2017 Copyright by Alexandra D. Varela 2017 ABSTRACT EXPLORING THE CONCEPT OF SELF-CREATIVITY THROUGH THE VALIDATION OF A NEW SURVEY MEASURE By Alexandra D. Varela December 2017 Dissertation supervised by Matthew J. Bundick, Ph.D. The purpose of this investigation was to validate a newly constructed instrument, the Creativity Assessment for the Malleability of Possible Selves (CAMPS) and, through that process, operationally define the newly developed construct of self-creativity. This dissertation utilizes three separate studies to validate the CAMPS and operationally define self-creativity, including samples intended to represent the general population (n = 199), professional counselors (n = 133), and exemplars of self-creativity (n = 13). -

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

Father-Daughter Relationship and Teen Pregnancy: an Examination of Adolescent Females Raised in Homes Without Biological Father

FATHER-DAUGHTER RELATIONSHIP AND TEEN PREGNANCY: AN EXAMINATION OF ADOLESCENT FEMALES RAISED IN HOMES WITHOUT BIOLOGICAL FATHERS A DISSERTATION IN Clinical Psychology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri – Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By AMBER M. HINTON-DAMPF B.S., University of Central Missouri, 2005 M.A., University of Missouri – Kansas City, 2010 Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 AMBER MARIE HINTON-DAMPF ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FATHER-DAUGHTER RELATIONSHIP AND TEEN PREGNANCY: AN EXAMINATION OF ADOLESCENT FEMALES RAISED IN HOMES WITHOUT BIOLOGICAL FATHERS Amber M. Hinton-Dampf, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT The aim of this dissertation was to further our knowledge of the processes underlying teenage pregnancy among adolescent females who are reared in “absent-father” homes (i.e., in homes without the biological father), a population at heightened risk for pregnancy. For this population, I hypothesized that the biological father-daughter relationship quality (FDRQ) as well as the stepfather-daughter relationship quality (SFDRQ) would predict the likelihood of teenage pregnancy, after controlling for sociodemographic risk factors and other known correlates of teen pregnancy. Further, based on the theory of “Father Hunger” (Fraiberg, 1959), two measures of need for intimacy (motivation to engage in sex and desire for a romantic relationship) were hypothesized to mediate the relationship between both FDRQ and SFDRQ and teenage pregnancy. Data were drawn from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health, Harris et al., 2009). The sample included 2,829 adolescent females whose biological father left their home prior to age 13, and approximately 12% of the sample (312) experienced a teenage pregnancy. -

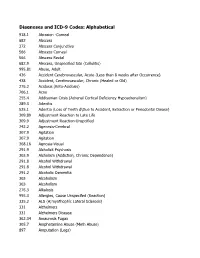

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings. -

Father Absence, Parental Care, and Female Reproductive Development

Evolution and Human Behavior 24 (2003) 376–390 Father absence, parental care, and female reproductive development Robert J. Quinlan* Department of Anthropology, Ball State University, 2000 West University Avenue, Muncie, IN 47306-0435, USA Received 10 February 2003; received in revised form 19 June 2003 Abstract This study examines female reproductive development from an evolutionary life history perspective. Retrospective data are for 10,847 U.S. women. Results indicate that timing of parental separation is associated with reproductive development and is not confounded with socioeconomic variables or phenotypic correlations with mothers’ reproductive behavior. Divorce/separation between birth and 5 years predicted early menarche, first sexual intercourse, first pregnancy, and shorter duration of first marriage. Separation in adolescence was the strongest predictor of number of sex partners. Multiple changes in childhood caretaking environment were associated with early menarche, first sex, first pregnancy, greater number of sex partners, and shorter duration of marriage. Living with either the father or mother after separation had similar effect on reproductive develop- ment. Living with a stepfather showed a weak, but significant, association with reproductive development, however, duration of stepfather exposure was not a significant predictor of devel- opment. Difference in amount and quality of direct parental care (vs. indirect parental investment) in two- and single-parent households may be the primary factor linking family environment to reproductive development. D 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Child development; Conjugal stability; Demography; Evolutionary ecology; Family environ- ment; Father absence; Life history; Menarche; Parental investment; Puberty; Reproductive strategies; Sexual behavior * Tel.: +1-765-285-8199. E-mail address: [email protected] (R.J. -

Dsm-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders Anorexia Nervosa

DSM-5 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR EATING DISORDERS ANOREXIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA To be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa according to the DSM-5, the following criteria must be met: 1. Restriction of energy intaKe relative to requirements leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. 2. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. 3. Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight. Even if all the DSM-5 criteria for anorexia are not met, a serious eating disorder can still be present. Atypical anorexia includes those individuals who meet the criteria for anorexia but who are not underweight despite significant weight loss. Research studies have not found a difference in the medical and psychological impacts of anorexia and atypical anorexia. BULIMIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA According to the DSM-5, the official diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa are: • Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: o Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances. o A sense of lacK of control over eating during the episode (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). -

Patients' and Carers' Perspectives of Psychopharmacological

Chapter Patients’ and Carers’ Perspectives of Psychopharmacological Interventions Targeting Anorexia Nervosa Symptoms Amabel Dessain, Jessica Bentley, Janet Treasure, Ulrike Schmidt and Hubertus Himmerich Abstract In clinical practice, patients with anorexia nervosa (AN), their carers and clini- cians often disagree about psychopharmacological treatment. We developed two corresponding questionnaires to survey the perspectives of patients with AN and their carers on psychopharmacological treatment. These questionnaires were dis- tributed to 36 patients and 37 carers as a quality improvement project on a specialist unit for eating disorders at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Although most patients did not believe that medication could help with AN, the majority thought that medication for AN should help with anxiety (61.1%), con- centration (52.8%), sleep problems (52.8%) and anorexic thoughts (55.6%). Most of the carers shared the view that drug treatment for AN should help with anxiety (54%) and anorexic thoughts (64.8%). Most patients had concerns about potential weight gain, increased appetite, changes in body shape and metabolism during psychopharmacological treatment. By contrast, the majority of carers were not concerned about these specific side effects. Some of the concerns expressed by the patients seem to be AN-related. However, their desire for help with anxiety and anorexic thoughts, which is shared by their carers, should be taken seriously by clinicians when choosing a medication or planning psychopharmacological studies. Keywords: anorexia nervosa, psychopharmacological treatment, treatment effects, side effects, opinion survey, patients, carers 1. Introduction 1.1 Anorexia nervosa Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an eating disorder. According to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1], its diagnostic criteria are significantly low body weight, intense fear of weight gain, and disturbed body perception. -

Effect of Self-Efficacy, Motivation and Anxiety on Online Academic Performance

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (Online) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (Print) Volume 9, Issue 2, April- June, 2021 DIP: 18.01.192.20210902, DOI: 10.25215/0902.192 http://www.ijip.in Research Paper Effect of Self-efficacy, Motivation and Anxiety on Online Academic Performance Ivor D’Souza1*, Dr Akriti Srivastava2 ABSTRACT As the number of online-learning users continues to increase, there is a need to understand the Effect of Self-efficacy, Motivation and Anxiety on Online Academic Performance. Through the online learning process, students can access the given information of teachers at any time on the respective online platform. The study aims to find out the Effect of Self- efficacy, Motivation and Anxiety on Online Academic Performance. It is comparatively more convenient in the current situation, because of the pandemic; every educational institute follows this learning method for properly giving education or lessons to their students. The study included 150 participants studying various courses at an Indian University. The mean age of participants was 19 years. The study consisted of 3 scales, the academic self-efficacy scale, the academic motivation scale and the state trait anxiety inventory. The researcher carried out a descriptive study to identify the aim of the study. Independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were carried out and the results of the study were analysed for the mentioned hypothesis. The study found that the mean scores of academic performances dropped in the individuals with low self-efficacy. Also, the mean scores of academic performances dropped in the individuals with low motivation. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:58 12 August 2016 Counseling Techniques](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5683/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-04-58-12-august-2016-counseling-techniques-1185683.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:58 12 August 2016 Counseling Techniques

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:58 12 August 2016 Counseling Techniques The third edition of Counseling Techniques: Improving Relationships with Others, Ourselves, Our Families and Our Environment enhances the author’s previous efforts to provide a comprehensive overview of counseling techniques in a manner that makes these theories accessible to students pursuing mental health professions, counselor educators, and seasoned practitioners alike. New to this edition is a chapter on play therapy and a host of other updates that illustrate ways to use different techniques in different situations with different populations. Counseling Techniques stresses the need to recognize and treat the client within the context of culture, ethnicity, interpersonal resources, and systemic support, and it shows the reader how to meet these needs using more than 500 treatment techniques, each of which is accompanied by step- by-step procedures and evaluation methods. Rosemary A. Thompson, EdD, LPC, NCC, NCSC has over 25 years of experience in public schools as a school counselor and administrator working with children, adolescents, and families. She taught concurrently in the department of counseling and human services at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, and was an associate professor in the school of psychology and counseling at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia. She is currently in private practice with Phoenix Mental Health Services, LLC, in Virginia Beach. Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:58 12 August 2016 Page Intentionally Left Blank Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:58 12 August 2016 Counseling Techniques Improving Relationships with Others, Ourselves, Our Families, and Our Environment Third Edition Rosemary A. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other