Dsm-V Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 9-2014 The mpI act of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology Julie A. Hewett Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hewett, Julie A., "The mpI act of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology" (2014). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 210. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY School of Behavioral Health in conjunction with the Faculty of Graduate Studies _______________________ The Impact of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology by Julie A. Hewett _______________________ A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology _______________________ September 2014 © 2014 Julie A. Hewett All Rights Reserved Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this dissertation in his/her opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a dissertation for the degree Doctor of Philosophy. , Chairperson Sylvia Herbozo, Assistant Professor of Psychology Jeffrey Mar, Assistant Clinical Professor, Psychiatry, School of Medicine Jason Owen, Associate Professor of Psychology David Vermeersch, Professor of Psychology iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. -

Obesity with Comorbid Eating Disorders: Associated Health Risks and Treatment Approaches

nutrients Commentary Obesity with Comorbid Eating Disorders: Associated Health Risks and Treatment Approaches Felipe Q. da Luz 1,2,3,* ID , Phillipa Hay 4 ID , Stephen Touyz 2 and Amanda Sainsbury 1,2 ID 1 The Boden Institute of Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise & Eating Disorders, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Science, School of Psychology, the University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] 3 CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, Brasília, DF 70040-020, Brazil 4 Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-02-8627-1961 Received: 11 May 2018; Accepted: 25 June 2018; Published: 27 June 2018 Abstract: Obesity and eating disorders are each associated with severe physical and mental health consequences, and individuals with obesity as well as comorbid eating disorders are at higher risk of these than individuals with either condition alone. Moreover, obesity can contribute to eating disorder behaviors and vice-versa. Here, we comment on the health complications and treatment options for individuals with obesity and comorbid eating disorder behaviors. It appears that in order to improve the healthcare provided to these individuals, there is a need for greater exchange of experiences and specialized knowledge between healthcare professionals working in the obesity field with those working in the field of eating disorders, and vice-versa. Additionally, nutritional and/or behavioral interventions simultaneously addressing weight management and reduction of eating disorder behaviors in individuals with obesity and comorbid eating disorders may be required. -

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Anorexia Nervosa

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Psychosom Med. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 July 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Psychosom Med. 2011 July ; 73(6): 491±497. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31822232bb. Post traumatic stress disorder in anorexia nervosa Mae Lynn Reyes-Rodríguez, Ph.D.1, Ann Von Holle, M.S.1, T. Frances Ulman, Ph.D.1, Laura M. Thornton, Ph.D.1, Kelly L. Klump, Ph.D.2, Harry Brandt, M.D.3, Steve Crawford, M.D.3, Manfred M. Fichter, M.D.4, Katherine A. Halmi, M.D.5, Thomas Huber, M.D.6, Craig Johnson, Ph.D.7, Ian Jones, M.D.8, Allan S. Kaplan, M.D., F.R.C.P. (C)9,10,11, James E. Mitchell, M.D. 12, Michael Strober, Ph.D.13, Janet Treasure, M.D.14, D. Blake Woodside, M.D.9,11, Wade H. Berrettini, M.D.15, Walter H. Kaye, M.D.16, and Cynthia M. Bulik, Ph.D.1,17 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 2 Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 4 Klinik Roseneck, Hospital for Behavioral Medicine, Prien and University of Munich (LMU), Munich, Germany 5 New York Presbyterian Hospital-Westchester Division, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, White Plains, NY 6 Klinik am Korso, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany 7 Eating Recovery Center, Denver, CO 8 Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom 9 Department of Psychiatry, The Toronto Hospital, Toronto, Canada 10 Center for -

GUIDEBOOK for NUTRITION TREATMENT of EATING DISORDERS

GUIDEBOOK for NUTRITION TREATMENT of EATING DISORDERS Authored by ACADEMY FOR EATING DISORDERS NUTRITION WORKING GROUP GUIDEBOOK for NUTRITION TREATMENT of EATING DISORDERS AUTHORED BY ACADEMY FOR EATING DISORDERS NUTRITION WORKING GROUP Jillian G. (Croll) Lampert, PhD, RDN, LDN, MPH, FAED; Chief Strategy Officer, The Emily Program, St. Paul, MN Therese S. Waterhous, PhD, CEDRD-S, FAED; Owner, Willamette Nutrition Source, Corvallis, OR Leah L. Graves, RDN, LDN, CEDRD-S, FAED; Vice President of Nutrition and Culinary Services, Veritas Collaborative, Durham, NC Julia Cassidy, MS, RDN, CEDRDS; Director of Nutrition and Wellness for Adolescent Programs, ED RTC Division Operations Team, Center for Discovery, Long Beach, CA Marcia Herrin, EdD, MPH, RDN, LD, FAED; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine and Owner, Herrin Nutrition Services, Lebanon, NH GUIDEBOOK FOR NUTRITION TREATMENT OF EATING DISORDERS ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction to this Guide . 1 2. Introduction to Eating Disorders . 1 3. Working with Individuals and Support Systems. 6 4. Nutritional Assessment for Eating Disorders . 7 5. Weight Stigma . .14 6. Body Image Concerns. .15 7. Laboratory Values Related to Nutrition Status . 18 8. Refeeding Syndrome . .23 9. Medications with Nutrition Implications . .26 10. Nutrition Counseling for Each Diagnosis. .31 11. Managing Eating Disordered-Related Behaviors . 42 12. Food Plans: Prescriptive Eating to Mindful and Intuitive Eating . 46 13. Treatment Approaches for Excessive Exercise/Activity . 48 14. Treatment Approach for Vegetarianism and Veganism . 50 15. Levels of Care. .55 16. Nutrition and Mental Function . 57 17. Conclusions . .59 GUIDEBOOK FOR NUTRITION TREATMENT OF EATING DISORDERS iii 1. INTRODUCTION TO THIS GUIDE Nutrition issues in AN: The diets of individuals with AN are typically low in calories, limited in This publication, created by the Academy for Eating variety, and marked by avoidance or fears about Disorders Nutrition Working Group, contains basic foods high in fat, sugar, and/or carbohydrates. -

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

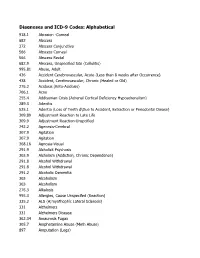

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Neural Correlates and Treatments Binge Eating Disorder

Running head: Binge Eating Disorder: Neural correlates and treatments Binge Eating Disorder: Neural correlates and treatments Bachelor Degree Project in Cognitive Neuroscience Basic level 22.5 ECTS Spring term 2019 Malin Brundin Supervisor: Paavo Pylkkänen Examiner: Stefan Berglund Running head: Binge Eating Disorder: Neural correlates and treatments Abstract Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most prevalent of all eating disorders and is characterized by recurrent episodes of eating a large amount of food in the absence of control. There have been various kinds of research of BED, but the phenomenon remains poorly understood. This thesis reviews the results of research on BED to provide a synthetic view of the current general understanding on BED, as well as the neural correlates of the disorder and treatments. Research has so far identified several risk factors that may underlie the onset and maintenance of the disorder, such as emotion regulation deficits and body shape and weight concerns. However, neuroscientific research suggests that BED may characterize as an impulsive/compulsive disorder, with altered reward sensitivity and increased attentional biases towards food cues, as well as cognitive dysfunctions due to alterations in prefrontal, insular, and orbitofrontal cortices and the striatum. The same alterations as in addictive disorders. Genetic and animal studies have found changes in dopaminergic and opioidergic systems, which may contribute to the severities of the disorder. Research investigating neuroimaging and neuromodulation approaches as neural treatment, suggests that these are innovative tools that may modulate food-related reward processes and thereby suppress the binges. In order to predict treatment outcomes of BED, future studies need to further examine emotion regulation and the genetics of BED, the altered neurocircuitry of the disorder, as well as the role of neurotransmission networks relatedness to binge eating behavior. -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings. -

Eating Disorders and Sexual Function Reviewed: a Trans-Diagnostic, Dimensional Perspective

Current Sexual Health Reports (2020) 12:1–14 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00236-w CLINICAL THERAPEUTICS (B MCCARTHY, R SEGRAVES AND R BALON, SECTION EDITORS) Eating Disorders and Sexual Function Reviewed: A Trans-diagnostic, Dimensional Perspective Cara R. Dunkley1,2 & Yana Svatko1 & Lori A. Brotto2,3 Published online: 18 January 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract Purpose of Review Clinical observation and a growing body of empirical research point to an association between disordered eating and sexual function difficulties. The present review identifies and connects the current knowledge on sexual dysfunction in the eating disorders, and provides a theoretical framework for conceptualizing the association between these important health conditions. Recent Findings Research on sexuality and eating pathology has focused on clinical samples of women with anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN). All aspects of sexual response can be impacted in women with an eating disorder, with sexual function in women with AN appearing to be more compromised than in women with BN. Research of this nature is extremely limited with respect to BED, non-clinical samples, men, and individuals with non-binary gender identities. Summary Sexuality should be examined and addressed within the context of eating disorder treatment. Sexual dysfunction and eating disorders, along with commonly comorbid disorders of anxiety and mood, can be seen as separate but frequently overlapping manifestations of internalizing psychopathology. Psychological, developmental, sociocultural, etiological, and bio- physical factors likely represent risk and maintenance factors for internalizing disorders. A dimensional, trans-diagnostic ap- proach to disordered eating and sexuality has promising implications for future research and clinical interventions. -

A Case–Control Study Investigating Food Addiction in Parkinson Patients Ingrid De Chazeron1*, F

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A case–control study investigating food addiction in Parkinson patients Ingrid de Chazeron1*, F. Durif2, C. Lambert3, I. Chereau‑Boudet1, M. L. Fantini4, A. Marques2, P. Derost2, B. Debilly2, G. Brousse1, Y. Boirie5,6 & P. M. Llorca1,2,3,4,5,6 Eating disorders (EDs) in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are mainly described through impulse control disorders but represent one end of the spectrum of food addiction (FA). Although not formally recognized by DSM‑5, FA is well described in the literature on animal models and humans, but data on prevalence and risk factors compared with healthy controls (HCs) are lacking. We conducted a cross‑ sectional study including 200 patients with PD and 200 age‑ and gender‑matched HCs. Characteristics including clinical data (features of PD/current medication) were collected. FA was rated using DSM‑5 criteria and the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns‑Revised (QEWP‑R). Patients with PD had more EDs compared to HCs (27.0% vs. 13.0%, respectively, p < 0.001). They mainly had FA (24.5% vs. 12.0%, p = 0.001) and night eating syndrome (7.0% vs. 2.5% p = 0.03). In PD patients, FA was associated with female gender (p = 0.04) and impulsivity (higher attentional non‑planning factor) but not with the dose or class of dopaminergic therapy. Vigilance is necessary, especially for PD women and in patients with specifc impulsive personality traits. Counterintuitively, agonist dopaminergic treatment should not be used as an indication for screening FA in patients with PD. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), compulsive eating is part of the spectrum of impulse control disorders (ICDs) that also include pathologic gambling, compulsive buying and hypersexuality1. -

Eating Disorders 101 Understanding Eating Disorders Anne Marie O’Melia, MS, MD, FAAP Chief Medical Officer Eating Recovery Center

Eating Disorders 101 Understanding Eating Disorders Anne Marie O’Melia, MS, MD, FAAP Chief Medical Officer Eating Recovery Center 1 Learning Objectives 1. List the diagnostic criteria and review the typical clinical symptoms for common eating disorders. 2. Become familiar with the biopsychosocial model for understanding the causes of eating disorders. 3. Understand treatment options and goals for eating disorder recovery 2 Declaration of Conflict of Interest I have no relevant financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider (s) of commercial services discussed in this CE/CME activity. 3 What is an eating disorder? Eating disorders are serious, life- threatening, multi-determined illnesses that require expert care. 4 Eating Disorders May Be Invisible • Eating disorders occur in males and females • People in average and large size bodies can experience starvation and malnourishment • Even experienced clinicians may not recognize the medical consequences of EDs 5 Importance of Screening and Early Detection . Delay in appropriate treatment results in – Associated with numerous med/psych/social complications – These may not be completely reversible – Long-lasting implications on development . Longer the ED persists, the harder it is to treat – Crude mortality rate is 4 - 5%, higher than any other psychiatric disorder (Crow et al 2009). – Costs for AN treatment and quality of life indicators, if progresses into adulthood, rivals Schizophrenia (Streigel- Moore et al, 2000). 6 AN-Diagnostic Criteria