Monitoring and Networking for Sea Turtle Conservation in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation Ltd., Mumbai 400 021

WEL-COME TO THE INFORMATION OF MAHARASHTRA TOURISM DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, MUMBAI 400 021 UNDER CENTRAL GOVERNMENT’S RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT 2005 Right to information Act 2005-Section 4 (a) & (b) Name of the Public Authority : Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (MTDC) INDEX Section 4 (a) : MTDC maintains an independent website (www.maharashtratourism. gov.in) which already exhibits its important features, activities & Tourism Incentive Scheme 2000. A separate link is proposed to be given for the various information required under the Act. Section 4 (b) : The information proposed to be published under the Act i) The particulars of organization, functions & objectives. (Annexure I) (A & B) ii) The powers & duties of its officers. (Annexure II) iii) The procedure followed in the decision making process, channels of supervision & Accountability (Annexure III) iv) Norms set for discharge of functions (N-A) v) Service Regulations. (Annexure IV) vi) Documents held – Tourism Incentive Scheme 2000. (Available on MTDC website) & Bed & Breakfast Scheme, Annual Report for 1997-98. (Annexure V-A to C) vii) While formulating the State Tourism Policy, the Association of Hotels, Restaurants, Tour Operators, etc. and its members are consulted. Note enclosed. (Annexure VI) viii) A note on constituting the Board of Directors of MTDC enclosed ( Annexure VII). ix) Directory of officers enclosed. (Annexure VIII) x) Monthly Remuneration of its employees (Annexure IX) xi) Budget allocation to MTDC, with plans & proposed expenditure. (Annexure X) xii) No programmes for subsidy exists in MTDC. xiii) List of Recipients of concessions under TIS 2000. (Annexure X-A) and Bed & Breakfast Scheme. (Annexure XI-B) xiv) Details of information available. -

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93)

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Odedra, Nathabhai K., 2009, “Ethnobotany of Maher Tribe In Porbandar District, Gujarat, India”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/eprint/604 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author ETHNOBOTANY OF MAHER TRIBE IN PORBANDAR DISTRICT, GUJARAT, INDIA A thesis submitted to the SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY In partial fulfillment for the requirement For the degree of DDDoDoooccccttttoooorrrr ooofofff PPPhPhhhiiiilllloooossssoooopppphhhhyyyy In BBBoBooottttaaaannnnyyyy In faculty of science By NATHABHAI K. ODEDRA Under Supervision of Dr. B. A. JADEJA Lecturer Department of Botany M D Science College, Porbandar - 360575 January + 2009 ETHNOBOTANY OF MAHER TRIBE IN PORBANDAR DISTRICT, GUJARAT, INDIA A thesis submitted to the SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY In partial fulfillment for the requirement For the degree of DDooooccccttttoooorrrr ooofofff PPPhPhhhiiiilllloooossssoooopppphhhhyyyy In BBoooottttaaaannnnyyyy In faculty of science By NATHABHAI K. ODEDRA Under Supervision of Dr. B. A. JADEJA Lecturer Department of Botany M D Science College, Porbandar - 360575 January + 2009 College Code. -

MUMBAI an EMERGING HUB for NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0

MUMBAI AN EMERGING HUB FOR NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0 FOREWORD Anuj Puri ANAROCK Group Group Chairman With the island city of Mumbai, Navi Mumbai contribution of the district to Maharashtra. Raigad and Thane reaching saturation due to scarcity of is preparing itself to contribute significantly land parcels for future development, Raigad is towards Maharashtra’s aim of contributing US$ expected to emerge as a new destination offering 1 trillion to overall Indian economy by 2025. The a fine balance between work and pleasure. district which is currently dominated by blue- Formerly known as Kolaba, Raigad is today one collared employees is expected to see a reverse of the most prominent economic districts of the in trend with rising dominance of white-collared state of Maharashtra. The district spans across jobs in the mid-term. 7,152 sq. km. area having a total population of 26.4 Lakh, as per Census 2011, and a population Rapid industrialization and urbanization in density of 328 inhabitants/sq. km. The region Raigad are being further augmented by massive has witnessed a sharp decadal growth of 19.4% infrastructure investments from the government. in its overall population between 2001 to 2011. This is also attributing significantly to the overall Today, the district boasts of offering its residents residential and commercial growth in the region, a perfect blend of leisure, business and housing thereby boosting overall real estate growth and facilities. uplifting and improving the quality of living for its residents. Over the past few years, Raigad has become one of the most prominent districts contributing The report titled ‘Raigad: Mumbai 3.0- An significantly to Maharashtra’s GDP. -

MDM Gujarat Review Mission Report, 2010 Page 1 MID DAY MEAL

MID DAY MEAL: REVIEW MISSION FOR GUJARAT Second Review Mission 19 – 25th, 2010 As part of 2nd Review Mission, a team consisting of Smt Rita Chatterjee, (Joint Sec-MDM, MHRD), Shri D.B. Mehta (Joint Commissioner -MDM, GOG), Ms. Sejal Dand (State Advisor to National Comm. Apptd. By Hon. Supreme Court in WPC 196/2001), Dr. Ankita Sharma (Consultant, UNICEF, Gandhinagar). Co member Dr. Anindita Shukla (Consultant, Food & Nutrition-MDM, NSG) visited Gujarat to see the implementation of the scheme. The team members would like to express gratitude to everyone who gave time, cooperation and hospitality during the visit. MDM Gujarat Review Mission Report, 2010 Page 1 Mid Day Meal Scheme National Programme of Mid Day Meal in Schools (MDMS) is a flagship programme of the Government of India aiming at addressing hunger in schools by serving hot cooked meal, helping children concentrate on classroom activities, providing nutritional support, encouraging poor children, belonging to disadvantaged sections, to attend school more regularly, providing nutritional support to children to drought-affected areas during summer vacation, studying in Government, Local Body and Government-aided primary and upper primary schools and the Centres run under Education Guarantee Scheme (EGS)/Alternative & Innovative Education (SSA) of all areas across the country. In drought- affected areas MDM is served during summer vacation also. Objectives of Joint Review Mission: 1. Review the system of fund flow from State Government to school/ cooking agency level and time taken in this process. 2. Review the management and monitoring system and its performance from State to school level. 3. Review the progress of the programme during 2010-11 with respect to availability of food grains and funds at the school/ cooking agency level, quality and regularity in serving the meal in the selected schools and districts, transparency in implementation role of teachers, involvement of community, convergence with school health Programme for supplementation of micronutrients and health check up etc. -

GUJARAT MARITIME BOARD (Government of Gujarat Undertaking) SAGAR BHAVAN, Sector 10-A, Opp

MARINE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR OBTAINING STATUTORY EC FOR DEVELOPMENT OF PORT INFRASTRUCTURE WITHIN EXISTING PORBANDAR PORT, GUJARAT Project Proponent GUJARAT MARITIME BOARD (Government of Gujarat Undertaking) SAGAR BHAVAN, Sector 10-A, Opp. Air Force Centre, CHH Rd, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382010 EIA Consultant Cholamandalam MS Risk Services Limited NABET Accredited EIA Consulting Organisation Certificate No: NABET/EIA/1011/011 PARRY House 3rd Floor, No. 2 N.S.C Bose Road, Chennai - 600 001 Tamil Nadu August 2018 Development of Port Infrastructure within PJ-ENVIR - 2017511-1253 existing Porbandar Port, Porbandar Village, Porbandar District, Gujarat DECLARATION BY PROJECT PROPONENT GMB has conducted the “EIA Study on “Development of Port Infrastructure within existing Porbandar Port, Porbandar Village, Porbandar District, Gujarat”. The EIA report preparation has been undertaken in compliance with the ToR issued by MoEF & CC. Information and content provided in the report is factually correct for the purpose and objective for such study undertaken. We hereby declare the ownership of contents (information and data) of EIA/EMP Report. For on behalf of Gujarat Maritime Board Signature: Name: Mr. Atul A. Sharma Designation: Deputy General Manager - Environment Cholamandalam MS Risk Services Page 1 Development of Port Infrastructure within PJ-ENVIR - 2017511-1253 existing Porbandar Port, Porbandar Village, Porbandar District, Gujarat DECLARATION BY EIA CONSULTANT EIA Study on “Development of Port Infrastructure within existing Porbandar Port, Porbandar Village, Porbandar District, Gujarat”. This EIA report has been prepared by Cholamandalam MS Risk Services Limited (CMSRSL), in line with EIA Notification, dated 14th September 2006, seeking prior Environmental Clearance from the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, New Delhi. -

MAHARASHTRA Not Mention PN-34

SL Name of Company/Person Address Telephone No City/Tow Ratnagiri 1 SHRI MOHAMMED AYUB KADWAI SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM A MULLA SHWAR 2 SHRI PRAFULLA H 2232, NR SAI MANDIR RATNAGI NACHANKAR PARTAVANE RATNAGIRI RI 3 SHRI ALI ISMAIL SOLKAR 124, ISMAIL MANZIL KARLA BARAGHAR KARLA RATNAGI 4 SHRI DILIP S JADHAV VERVALI BDK LANJA LANJA 5 SHRI RAVINDRA S MALGUND RATNAGIRI MALGUN CHITALE D 6 SHRI SAMEER S NARKAR SATVALI LANJA LANJA 7 SHRI. S V DESHMUKH BAZARPETH LANJA LANJA 8 SHRI RAJESH T NAIK HATKHAMBA RATNAGIRI HATKHA MBA 9 SHRI MANESH N KONDAYE RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 10 SHRI BHARAT S JADHAV DHAULAVALI RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 11 SHRI RAJESH M ADAKE PHANSOP RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 12 SAU FARIDA R KAZI 2050, RAJAPURKAR COLONY RATNAGI UDYAMNAGAR RATNAGIRI RI 13 SHRI S D PENDASE & SHRI DHAMANI SANGAM M M SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR EHSWAR 14 SHRI ABDULLA Y 418, RAJIWADA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI TANDEL RI 15 SHRI PRAKASH D SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM KOLWANKAR RATNAGIRI EHSWAR 16 SHRI SAGAR A PATIL DEVALE RATNAGIRI SANGAM ESHWAR 17 SHRI VIKAS V NARKAR AGARWADI LANJA LANJA 18 SHRI KISHOR S PAWAR NANAR RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 19 SHRI ANANT T MAVALANGE PAWAS PAWAS 20 SHRI DILWAR P GODAD 4110, PATHANWADI KILLA RATNAGI RATNAGIRI RI 21 SHRI JAYENDRA M DEVRUKH RATNAGIRI DEVRUK MANGALE H 22 SHRI MANSOOR A KAZI HALIMA MANZIL RAJAPUR MADILWADA RAJAPUR RATNAGI 23 SHRI SIKANDAR Y BEG KONDIVARE SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR ESHWAR 24 SHRI NIZAM MOHD KARLA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 25 SMT KOMAL K CHAVAN BHAMBED LANJA LANJA 26 SHRI AKBAR K KALAMBASTE KASBA SANGAM DASURKAR ESHWAR 27 SHRI ILYAS MOHD FAKIR GUMBAD SAITVADA RATNAGI 28 SHRI -

04032020Za1dyf5aseacminut

Minutes of the 580 th meeting of the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee held on 07/01/2020 at GPCB, Sector 10A, Gandhinagar. The 580 th meeting of the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC) was held on07 th January 2020 at GPCB, Sector 10A, Gandhinagar. Following members attended the meeting: 1. Dr. Dinesh Misra, Chairman, SEAC 2. Shri Satish Srivastav, Vice Chairman, SEAC 3. Shri V. N. Patel, Member, SEAC 4. Shri R.J.Shah, Member, SEAC 5. Shri A.K.Muley, Member, SEAC Following proposals were considered during meeting. 1. LIMESTONE MINING PROJECT,DIST: JUNAGADH (VIOLATION APPRAISAL ) TOR File Name S Villag Ta Dist Lease ROM Nearest Minera SEAC NO NO e area in human l TOR Ha habitati Meetin on g SIA/GJ/MIN/ Damasa 110/ Dama Una Junagadh 2.00 57500 Una:7.7 LIMES 29/08/ Lime P sa Ha MTPA 0 km TONE 2018 44972/2019 Stone Mining Project, TOR (c/o Shree SIA/GJ/MIN/ Vikram 26379/2018 Chemical Co. Project proponent attended the meeting and informed that they could not submit the hard copies of final EIA and Approved Mine plan. Committee noted that hard copies of final EIA and approved mine plan along with other documents are not submitted by the PP. Hence, after deliberation, it is decided to defer the proposal in one of the upcoming SEAC meeting. th 580 meeting of SEAC-Gujarat, Dated 07.01.2020 2. LIMESTONE MINING PROJECT,DIST: JUNAGADH (VIOLATION APPRAISAL ) TOR File Name S Villag Ta Dist Lease ROM Nearest Minera SEAC NO NO e area in human l TOR Ha habitati Meetin on g SIA/GJ/MIN/ Shri 389 Ajotha Ver Junagad 2.00 Ha 46,300 Ajotha:1 Limest 29/08/ ArjabhaiKhi aval h MTPA .58 km one 2018 44550/2019 mabhai Rathod,(Li me stone (TOR mine lease Proposal Area: 2.00 NO: SIA /GJ Ha / MIN /23285 /2018). -

[email protected]

STATE BANK OF INDIA, LEAD BANK DEPARTMENT, 2nd Floor, Manek Chowk Branch, PORBANDAR – 360575. Phone No.0286-2248413 (M) 7600035219 Email : [email protected] To, Date: 05/03/2019 ___________________________ ___________________________ ___________________________ Dear Sir, MINUTES OF DLRC & DLCC MEETINGS FOR THE QUARTER ENDED DECEMBER-2018 HELD ON 26.02.2019. We forward herewith the minutes of the above meetings for your perusal, record and necessary action. Please keep us informed about the action taken/ Plan on decisions pertaining to your institution so that the same can be placed before the House in the next meeting. Please submit your compliance / action taken report for onwards submission to RBI/SLBC. Yours Faithfully, Chief Manager & Convener (DLRC-DLCC) Porbandar 05/03/2019 Encl: as above. Minutes of the DLRC / DLCC meeting held on 26/02/2019: The meeting of the DLRC/DLCC of Porbandar District was convened at 17:00 hrs on 26/02/2019 at the Conference Hall of Collectorate Office, Porbandar to review the performance for the quarter ended December -2018 and ACP 2018-19 under various parameters of banking. At the outset Shri Ajit Singh [LDM] expressed thanks to all the members for their valuable presence and requested Shri M. H. Joshi RAC/Additional District Magistrate, Porbandar to preside over the meeting. Shri Ajit Singh LDM welcomed all dignitaries and participants on behalf of Lead Bank Office, Porbandar and thereafter took up the agenda wise discussion with the permission of the chair. After some time The District Collector Shri Mukesh A. Pandya (IAS) Joined and chaired the meeting. -

Download Download

ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) OPEN ACCESS ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) 26 October 2018 (Online & Print) Vol. 10 | No. 11 | 12443–12618 10.11609/jot.2018.10.11.12443-12618 www.threatenedtaxa.org Building evidence for conservatonJ globally TTJournal of Threatened Taxa YOU DO ... ... BUT I DON’T SEE THE DIFFERENCE. ISSN 0974-7907 (Online); ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Published by Typeset and printed at Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society Zoo Outreach Organizaton No. 12, Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampat - Kalapat Road, Saravanampat, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Ph: 0 938 533 9863 Email: [email protected], [email protected] www.threatenedtaxa.org EDITORS Christoph Kuefer, Insttute of Integratve Biology, Zürich, Switzerland Founder & Chief Editor Christoph Schwitzer, University of the West of England, Clifon, Bristol, BS8 3HA Dr. Sanjay Molur, Coimbatore, India Christopher L. Jenkins, The Orianne Society, Athens, Georgia Cleofas Cervancia, Univ. of Philippines Los Baños College Laguna, Philippines Managing Editor Colin Groves, Australian Natonal University, Canberra, Australia Mr. B. Ravichandran, Coimbatore, India Crawford Prentce, Nature Management Services, Jalan, Malaysia C.T. Achuthankuty, Scientst-G (Retd.), CSIR-Natonal Insttute of Oceanography, Goa Associate Editors Dan Challender, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Dr. B.A. Daniel, Coimbatore, India D.B. Bastawade, Maharashtra, India Dr. Ulrike Streicher, Wildlife Veterinarian, Danang, Vietnam D.J. Bhat, Retd. Professor, Goa University, Goa, India Ms. Priyanka Iyer, Coimbatore, India Dale R. Calder, Royal Ontaro Museum, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Dr. Manju Siliwal, Dehra Dun, India Daniel Brito, Federal University of Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil Dr. Meena Venkataraman, Mumbai, India David Mallon, Manchester Metropolitan University, Derbyshire, UK David Olson, Zoological Society of London, UK Editorial Advisors Davor Zanella, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croata Ms. -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

April 2013-March 2014)

Annual Report (April 2013-March 2014) Paryavaran Mitra (Janvikas) Annual Report (April 2013 – March 2014) Paryavaran Mitra 502, Raj Avenue, Bhaikakanagar Road, Thaltej, Ahmedabad 380059 Ph: 079-26851321, 26851801 Telefax: 079-26851321 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.paryavaranmitra.org.in Paryavaran Mitra, Ahmedabad Annual Report (April 2013-March 2014) Contents Chapter 1: Environmental Public Hearing 1. Our objective 2. Our Role 3. Strategy 4. EPH: April 2013-March 2014 5. Some Important Environmental public hearings Chapter 2: Combating Climate Change 1. Intervention in CDM projects 2. Paryavaran Mitra’s interventions 3. Participation in Warsaw 4. Other Activities Chapter 3: Advocacy 1. Advocacy through RTI 2. Advocacy through comments on various provisions 3. Intervention through NGT 4. Advocacy by associating with Gujarat Social Watch 5. Advocacy through media 6. Advocacy through correspondence Chapter 4: Awareness 1. Paryavaran Mitra - Bimonthly newsletter 2. Environmental Paralegals-rural Outreach 3. Other awareness activities 4. Awareness through media Chapter 5: Networking 1. Student internship 2. Individual Participation 3. Linkages with other networks Chapter 6: Towards Self Sustainability Annexures: 1. Details of EPH report from April 2013 to March 2014 Paryavaran Mitra, Ahmedabad Annual Report (April 2013-March 2014) 2. Some important EPHs 3. List of RTI applications 4. List of interns at Paryavaran Mitra from April 2013 to March 2014 5. Individual participation by Paryavaran Mitra Paryavaran Mitra, Ahmedabad -

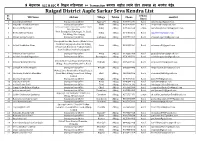

Raigad District Aaple Sarkar Seva Kendra List Sr

जे कधारक G2C & B2C चे मळून महयाला ५० Transaction करणार नाहत यांचे सटर तकाळ बंद करणेत येईल. Raigad District Aaple Sarkar Seva Kendra List Sr. Urban/ VLE Name Address Village Taluka Phone email id No. Rural 1 Sonali Sharad Mithe Grampanchyat Office Agarsure Alibag 7066709270 Rural [email protected] 2 Priyanka Chandrakant Naik Grampanchyat Office Akshi Alibag 8237414282 Rural [email protected] Maha-E-Seva Kendra Alibag Court Road Near Tahasil 3 Karuna M Nigavekar Office Alibag Alibag Alibag Alibag 9272362669 urban [email protected] Near Dattapada, Dattanagar, Po. Saral, 4 Neeta Subhash Mokal Alibag Alibag 8446863513 Rural [email protected] Tal. Alibag, Dist. Raigag 5 Shama Sanjay Dongare Grampanchyat Office Ambepur Alibag 8087776107 Rural [email protected] Sarvajanik Suvidha Kendra (Maha E Seva Kendra) Ranjanpada-Zirad 18 Alibag 6 Ashish Prabhakar Mane Awas Alibag 8108389191 Rural [email protected] Revas Road & Internal Prabhat Poultry Road Prabhat Poultry Ranjanpada 7 hemant anant munekar Grampanchyat Office Awas Alibag 9273662199 Rural [email protected] 8 Ashvini Aravind Nagaonkar Grampanchyat Office Bamangaon Alibag 9730098700 Rural [email protected] 262, Rohit E-Com Maha E-Seva Kendra, 9 Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak Belkade Alibag 9579327202 Rural [email protected] Alibag - Roha Road Belkade Po. Kurul 10 Santosh Namdev Nirgude Grampanchyat Office Beloshi Alibag 8983604448 Rural [email protected] Maha E Seva Kendra Bhal 4 Bhal Naka St 11 Shobharaj Dashrath Bhendkar Stand Bhal,