Protestant Evangelicals and Recent American Politics ( プロテスタント福音派と近年のアメリカ政治)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America in Latin America Power and Political Evangelicals JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE We are a political foundation that is active One of the most noticeable changes in Latin America in 18 forums for civic education and regional offices throughout Germany. during recent decades has been the rise of the Evangeli- Around 100 offices abroad oversee cal churches from a minority to a powerful factor. This projects in more than 120 countries. Our José Luis Pérez Guadalupe is a professor applies not only to their cultural and social role but increa- headquarters are split between Sankt and researcher at the Universidad del Pacífico Augustin near Bonn and Berlin. singly also to their involvement in politics. While this Postgraduate School, an advisor to the Konrad Adenauer and his principles Peruvian Episcopal Conference (Conferencia development has been evident to observers for quite a define our guidelines, our duty and our Episcopal Peruana) and Vice-President of the while, it especially caught the world´s attention in 2018 mission. The foundation adopted the Institute of Social-Christian Studies of Peru when an Evangelical pastor, Fabricio Alvarado, won the name of the first German Federal Chan- (Instituto de Estudios Social Cristianos - IESC). cellor in 1964 after it emerged from the He has also been in public office as the Minis- first round of the presidential elections in Costa Rica and Society for Christian Democratic Educa- ter of Interior (2015-2016) and President of the — even more so — when Jair Bolsonaro became Presi- tion, which was founded in 1955. National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (Institu- dent of Brazil relying heavily on his close ties to the coun- to Nacional Penitenciario del Perú) We are committed to peace, freedom and (2011-2014). -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

Patterns of Political Donations in New Zealand Under MMP: 1996-2019

Patterns of political donations in New Zealand under MMP: 1996-2019 Thomas Anderson and Simon Chapple Working Paper 20/05 Working Paper 20/02 2020 INSTITUTE FOR GOVERNANCE AND POLICY STUDIES WORKING PAPER 20/05 MONTH/YEAR November 2020 AUTHOR Thomas Anderson and Simon Chapple INSTITUTE FOR GOVERNANCE AND School of Government POLICY STUDIES Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington 6140 New Zealand For any queries relating to this working paper, please contact [email protected] DISCLAIMER The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are strictly those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, the School of Government or Victoria University of Wellington. Introduction The issue of political donations in New Zealand is regularly in the news. While the media report on their immediately newsworthy dimensions, no systematic data work has been done on political donations in New Zealand in the Mixed Member Proportional electoral system (MMP) period. The most comprehensive analysis covering the first part of the MMP period and before, which is now somewhat dated but contains a good summary of the existing literature, is in Bryce Edwards’s doctoral thesis (Edwards, 2003), especially Chapter Seven, “Party Finance and Professionalisation”. Donations are, of course, a subset of sources of Party finance, and it is in this context that Edwards deals with them. He draws eclectically on several sources for his qualitative and quantitative analysis, including largely descriptive work of political scientists, government reports, former politicians’ memoirs, historians and media reports, as well as using data on donations from the Electoral Commission. -

Attica Correctional Facility Were False." ATTICA, N.Y., Sept

A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Afirsthand report BY DERRICK MORRISON side the Attica Correctional Facility were false." ATTICA, N.Y., Sept. 15-"Time would Monday, Sept. 13, around 11 a.m., Oswald's denial of "throat-slittings" have meant nothing here but lives, rang tr~er and truer as the hours and "castrations" and other "atroci and I thought lives were more im passed. Today the Buffalo Courrier ties" was forced in the wake of an portant than four days or eight days Express carried a bulletin reading: autopsy report from the Monroe or 10 days .... They (the inmates) " State Correction Commissioner Rus County Medical Examiner's office in told us yesterday (Sunday) no hos sell G. Oswald confirmed Tuesday Rochester. That report held that ni ne tages would be harmed if the police night that nine of the 10 hostages of the 10 hostages died of gunshot did not come in. They (hostages) who died in the Attica prison riot wounds. would have been alive, the ones who succumbed to gunshot wounds fired This sensational disclosure clearly died, right now." by state police during the retaking of demonstrates that the blood, the will These words, by the prominent civ- the maximum security facility Monday ful and deliberate murder of 32 in il liberties attorney William Kunstler, morning. He said that earlier reports mates and 10 guards and civilian spoken to me and other reporters out- that the hostages died of cut throats Continued on page 5 M.t\..JORITY . :oF- NEW . VOTERS ARE NONCOLLEGE ing $135 a month, were provided with pest-ridden,. -

Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election

A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION JACK VOWLES, HILDE COFFÉ AND JENNIFER CURTIN Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Vowles, Jack, 1950- author. Title: A bark but no bite : inequality and the 2014 New Zealand general election / Jack Vowles, Hilde Coffé, Jennifer Curtin. ISBN: 9781760461355 (paperback) 9781760461362 (ebook) Subjects: New Zealand. Parliament--Elections, 2014. Elections--New Zealand. New Zealand--Politics and government--21st century. Other Creators/Contributors: Coffé, Hilde, author. Curtin, Jennifer C, author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of figures . vii List of tables . xiii List of acronyms . xvii Preface and acknowledgements . .. xix 1 . The 2014 New Zealand election in perspective . .. 1 2. The fall and rise of inequality in New Zealand . 25 3 . Electoral behaviour and inequality . 49 4. The social foundations of voting behaviour and party funding . 65 5. The winner! The National Party, performance and coalition politics . 95 6 . Still in Labour . 117 7 . Greening the inequality debate . 143 8 . Conservatives compared: New Zealand First, ACT and the Conservatives . -

The Future of the Evangelical-Republican Coalition

Excerpt • Temple University Press Introduction Paul A. Djupe Ryan L. Claassen hat is a crackup? Dictionaries offer a range of meanings. Oxford Living Dictionaries reports “crack up” as a phrasal verb meaning to “suffer W an emotional breakdown under pressure” or to “burst into laughter.”1 Merriam-Webster adds “to damage.”2 It is safe to say that the state of the re- lationship between the Republican Party and white evangelicals is no laugh- ing matter and that our meaning tracks best with “strain.”3 As 2016 ticked along, we wondered whether the Republican Party was on a path that would strain, damage, or destroy the coalition with evangelicals. The election re- sults, however, saw evangelicals double-down on Republican loyalty. When we began to write this book, we were confronted with a rather unexpected fact pattern. The unusual events of 2016 shined new light on the political priorities of evangelicals and what they expect from the Republican Party. Whether there was a crackup or not, 2016 was a gift to those who study reli- gion and politics. The unprecedented candidates and events of the presidential election let us see seams that had not been exposed for decades. Put differently, when evangelicals do things that are consistent with Republican priorities and Re- publicans do things that are consistent with evangelical priorities, it is al- most impossible to study what causes what. The 2016 election was different. It presented evangelical elites advocating against Republicans, Republican infighting, a Republican nominee far from evangelical orthodoxy, and can- didates other than the eventual winner with far better conservative Chris- tian bona fides. -

The Causes and Consequences of New Zealand's Adoption of Mmp

'ALL IS CHANGED, CHANGED UTTERLY'? — THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF NEW ZEALAND'S ADOPTION OF MMP Andrew Geddis* and Caroline Morris** New Zealand's political landscape experienced a seismic shift in 1993, when the country replaced the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) voting system it had inherited from its British colonial past with a new Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) voting system. The move had immediate and deep ramifications for a whole range of issues: the range of interests represented in Parliament;1 the way that governments are formed and function;2 how the country's public sector agencies operate;3 the manner in which its electoral participants conduct their campaigns;4 and so on. Indeed, it is not too much of an exaggeration to say that every area of New Zealand's public and political life was touched in some fashion by the general 'systems change' produced by the country's decision to embrace MMP.5 These changes have effected shifts in what may be termed the 'political culture' of New Zealand; re-alignments in the relationships between various public and political institutions and bodies; as well as alterations to the formal legal rules that govern these institutions and bodies. Any sort of full and comprehensive consideration of the extent and nature of these various changes would require a book-length study, if not a multi-volume work. Therefore, the present article has relatively modest ambitions.6 With almost a decade's worth of experience of 'MMP-in-practice' to reflect upon, we trace how this _____________________________________________________________________________________ * Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Otago (andrew.geddis@stonebow. -

Populism and Electoral Politics in New Zealand

A POPULIST EXCEPTION? THE 2017 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION A POPULIST EXCEPTION? THE 2017 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION EDITED BY JACK VOWLES AND JENNIFER CURTIN Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463854 ISBN (online): 9781760463861 WorldCat (print): 1178915541 WorldCat (online): 1178915122 DOI: 10.22459/PE.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Green Party leader James Shaw standing in ‘unity’ at the stand up after the ‘Next steps in Government’s Plan for NZ’ speech at AUT, Auckland. © Stuff Limited. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables . vii Acknowledgements . xiii Jennifer Curtin and Jack Vowles The Populist Exception? The 2017 New Zealand General Election . 1 Jack Vowles, Jennifer Curtin and Fiona Barker 1 . Populism and Electoral Politics in New Zealand . 9 Fiona Barker and Jack Vowles 2 . Populism and the 2017 Election—The Background . 35 Jack Vowles 3 . Measuring Populism in New Zealand . 71 Lara Greaves and Jack Vowles 4 . Populism, Authoritarianism, Vote Choice and Democracy . 107 Jack Vowles 5 . Immigration and Populism in the New Zealand 2017 Election . 137 Kate McMillan and Matthew Gibbons 6 . Gender, Populism and Jacinda Ardern . 179 Jennifer Curtin and Lara Greaves 7 . -

Catholicism and Democracy: a Reconsideration

Catholicism and Democracy A Reconsideration Edward Bell Brescia University College at the University of Western Ontario Introduction [1] It has long been believed that there is a relationship between a society‟s culture and its ability to produce and sustain democratic forms of government. The ancient Athenians maintained that their democracy depended, in part, on the fostering of “civic virtue” or democratic culture. Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and J. S. Mill also maintained that culture and democracy were related, and a wide variety of social scientists have come to broadly similar conclusions. For example, the cultural argument appears in S. M. Lipset‟s highly influential explanation of how democracy arises and is sustained (1959; 1981: chaps. 2-3; 1990; 1994). Lipset claims that democracy “requires a supportive culture, the acceptance by the citizenry and political elites of principles underlying freedom of speech, media, assembly, religion, of the rights of opposition parties, of the rule of law, of human rights, and the like” (1994: 3). He even claims that cultural factors appear to be more important than economic ones in accounting for the emergence and stability of democracy (1994: 5; see also 1990). Similarly, Almond and Verba argue that a certain “civic culture” is necessary for the establishment of democracy, and that this sort of culture is not easily transferable to non- Western countries (5). Such conclusions have been echoed by many other writers and researchers (e.g., Kennan: 41-43; Bendix: 430; Tumin: 151; Inglehart 1988, 1990, 1997; Putnam; Granato, Inglehart and Leblang; Bova: 115). [2] It follows from the cultural argument that some national cultures and religions are more conducive to democracy than others. -

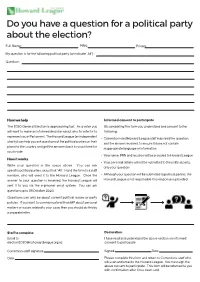

Do You Have a Question for a Political Party About the Election?

Do you have a question for a political party about the election? Full Name: PRN: Prison: My question is for the following political party (or indicate “All”) : Question: How we help Informed consent to participate The 2020 General Election is approaching fast. As a voter you By completing this form you understand and consent to the will want to make an informed decision about who to vote for to following: represent you in Parliament. The Howard League (an independent • Corrections and Howard League staff may read the question, charity) can help you ask questions of the political parties on their and the answer received, to ensure it does not contain plans for the country, and get the answers back to you in time for inappropriate language or information you to vote. • Your name, PRN and location will be provided to Howard League How it works • Your personal details will not be submitted to the political party; Write your question in the space above. You can ask only your question specific political parties, or just tick “All”. Hand the form to a staff member, who will send it to the Howard League. Once the • Although your question will be submitted to political parties, the answer to your question is received, the Howard League will Howard League is not responsible if no response is provided sent it to you via the e-prisoner email system. You can ask questions up to 09 October 2020. Questions can only be about current political issues or party policies. If you want to communicate with an MP about personal matters or issues related to your case, then you should do this by a separate letter. -

Israel and Evangelicals and the Two-Front War for Jewish Votes

Politics and Religion, 2 (2009), 395–419 # Religion and Politics Section of the American Political Science Association, 2009 doi:10.1017/S1755048309990198 1755-0483/09 $25.00 Identity versus Identity: Israel and Evangelicals and the Two-Front War for Jewish Votes Eric M. Uslaner and Mark Lichbach University of Maryland—College Park Abstract: Republicans made major efforts to win a larger share of the Jewish vote in 2004 by emphasizing their strong support for Israel. They partially succeeded, but did not make a dent in the overall loyalty of American Jews to the Democratic party, since they lost approximately as many votes because of Jews’ negative reactions to the party’s evangelical base. We argue that both Israel and worries over evangelical influence in the country reflect concerns about Jewish identity, above and beyond disagreements on specific social issues. We compare American Jewish voting behavior and liberalism to the voting behavior of non-Jews in 2004 using a survey of Jews from the National Jewish Democratic Coalition and the American National Election Study. For non-Jews, attitudes toward evangelicals are closely linked to social issues, but for Jews this correlation is small. The Jewish reaction to evangelicals is more of an issue of identity and the close ties of evangelicals to the Republican Party keep many Jews Democratic. Attitudes toward evangelicals are far more important for Jewish voting behavior than for non- Jewish voters. We are grateful to Ira Forman of the National Jewish Democratic Council for providing us with the data and to Patrick McCreesh of Greenberg Research for technical advice on the sampling frame and the data set. -

Electoral Commission Te Kaitiaki Take Kōwhiri for the Year Ended 30 June 2005

E.57 Annual Report of the Electoral Commission Te Kaitiaki Take Kōwhiri for the year ended 30 June 2005 Prepared and presented in accordance with sections 150 - 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004 for presentation to the House of Representatives by the Minister of Justice. Vision New Zealand’s electoral framework and processes are widely used, understood, trusted and valued. Directory Street address: Level 6, Greenock House, 39 The Terrace, Wellington Postal address: P O Box 3050, Wellington Telephone number: +64 4 474 0670 Facsimile number: +64 4 474 0674 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.elections.org.nz Accountants: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Auditor: Audit New Zealand Bankers: WestpacTrust Solicitors: Crown Law Office ISSN: 1174-3727 Contents Letter of Transmittal ................................................................................................................4 Part 1: Year in review...............................................................................................................5 Vision ..................................................................................................................................5 Achievement highlights........................................................................................................5 Organisational........................................................................................................................................... 5 Registered political parties and logos......................................................................................................