A Profile of British Jewry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

A Synagogue for All Families: Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues

A Synagogue for All Families Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues Introduction Across North America, Conservative kehillot (synagogues) create programs, policies, and welcoming statements to be inclusive of interfaith families and to model what it means for 21st century synagogues to serve 21 century families. While much work remains, many professionals and lay leaders in Conservative synagogues are leading the charge to ensure that their community reflects the prophet Isaiah’s vision that God’s house “shall be a house of prayer for all people” (56:7). In order to share these congregational exemplars with other leaders who want to raise the bar for inclusion of interfaith families in Conservative Judaism, the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) and InterfaithFamily (IFF) collaborated to create this Interfaith Inclusion Resource for Conservative Synagogues. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point. This document highlights 10 examples where Conservative synagogues of varying sizes and locations model inclusivity in marketing, governance, pastoral counseling and other key areas of congregational life. Our hope is that all congregations will be inspired to think as creatively as possible to embrace congregants where they are, and encourage meaningful engagement in the synagogue and the Jewish community. We are optimistic that this may help some synagogues that have not yet begun the essential work of the inclusion of interfaith families to find a starting point that works for them. Different synagogues may be in different places along the spectrum of welcoming and inclusion. Likewise, the examples presented here reflect a spectrum, from beginning steps to deeper levels of commitment, and may evolve as synagogues continue to engage their congregants in interfaith families. -

The Lives of the Jews of Horažd'ovice

The lives of the Jews of Horažd’ovice In Memoriam WESTMINSTER SYNAGOGUE Our community’s visit to Horažďovice confirmed that no brutality or oppression can ever destroy the spirit of humanity. #e inhabitants of that little town not only showed us their respect and love for those who were so cruelly taken from their midst but also that no amount of fear placed into people’s minds and hearts whether it was through fascism or communism can destroy the spark of godly spirit implanted within us. #e preservation of the Horažďovice scroll and the scrolls from other Czech cities is a reminder of our duty to foster their memories both within the Jewish community and outside, to pass it on to our children and to future generations, forming a chain strong enough to always overcome. It also tells us how important it is to respect one another and not allow prejudice to rear its ugly head. #ere has to be tolerance and understanding and our role here, with our friends in Horažďovice and with the world at large, is to ensure that this never ever should happen again. We must be vigilant and never remain silent in the face of danger or where truth is at stake. We owe this duty to all those who have perished in the horrors of the Holocaust and also to those who today, in different parts of the World, suffer because they are seemingly different. Humanity is only one, just as there is One God whose watchword we say twice a day, Hear O Israel the Lord our God the Lord is One. -

1 MS 142 AJ 416 Archives of the London Board of Shechita 1/1

1 MS 142 AJ 416 Archives of the London Board of Shechita 1/1 Correspondence with the Spanish and Portuguese Jews Congregation 1953-68 1/2 Correspondence with the Federation of Synagogues 1962-7 1/3 Correspondence: Jacob George 1967 Black and white photographs of the Israeli Restaurant 1/4 Correspondence: rents, electricity and other service charges 1967-8 1/5 Correspondence with the Liverpool Board of Shechita 1968-72 1/6 Correspondence with the Leeds Board of Shechita 1969-71 2/1 Correspondence with the Bournemouth Hebrew Congregation 1965-7 2/2 Correspondence: distribution of Kosher meat 1965-72 2/3 Correspondence: Kosher meat distribution depot 1969-71 2/4 Correspondence with Halford, Shead and Company 1970-1 2/5 Licences of shochetim 1968-9 3/1 General accounts with Joseph Sebag and Company 1965-9 3/2 General revenue account sheets 1969-70 3/3 Investment papers 1965-7 3/4 Investment papers, verification of stock 1966-7 3/5 Investment papers 1968 4 Correspondence: proposed new abattoir and Kosher meat distribution 1965-6 5/1 Correspondence: poultry abattoir 1970-2 5/2 Committee papers and associated papers 1971-2 6/1 Correspondence: terefah butchers 1970 6/2 Telegrams 1964-8 6/3 Correspondence, posters, black and white photographs: terefah butchers 7/1 Correspondence with the General Board of Shechita of Eire 1959-65 7/2 Correspondence: trade descriptions act of 1968 1969-71 8/1 Correspondence with the Board of Deputies of British Jews 1959-66 8/2 Papers relating to the case of M.Lederman 8/3 Union of Jewish Women report 1970 9/1 Correspondence -

JEW HATRED Anti-Semitism in Emulate the Growth and Influence of Its European Counterparts

CJM OWALJUSIKWHS JEW HATRED Anti-Semitism in emulate the growth and influence of its European counterparts. Groups such as Britain Today the British National Party are scorned by the vast majority of Britons and are Anti-Semitism is, in many ways, the relatively powerless in the mainstream precursor of the racist attitudes now political process. projected by European societies on the The Far Right's influence, however, visible ethnic minorities within their on racial and political tension and midst. Jews remain the primary, violence, is manifest in localised areas of ideological, target for hard-core racists, power across the country. Racial attacks but the vast bulk of societal racism, in Tower Hamlets increased by over prejudice and actual physical attacks are 300% following the BNP's Millwall Edmonton Cemetery April 1990 directed against visible minority groups council seat election success in of Afro-Caribbean, India sub-continent, September '93. The Millwall victory (Nov '92); and the initial Allied air strikes or North African origin. This is confirmed (since overturned in the May '94 local against Iraq (Jan '91). by a number of recent opinion polls elections) gave an unprecedented boost The next highest increase followed conducted throughout Europe and Britain to the BNP's morale and public profile. the highly publicised desecration of the by the American Jewish Committee in Jewish cemetery in Carpentras, France which Jews were consistently viewed Anti-Semitic Incidents and Attacks (May '90). This is an indicator of the more favourably than other minority Anglo-Jewry's representative body, the influence of publicity on racist attacks, a groups. -

Annual Review 2019 Contents

Annual Review 2019 Contents A word from the Chief Executive 3 A word from the Chairman 4 Introduction from a member 5 Our vision 6 Our mission 6 Employment 7 New Chapters 8 Langdon Brady Club 9 Langdon College 10 Supported Living 11 Social 12 Volunteering 13 Jewish Culture 14 Fundraising & events 15 Our financial year 16 Employers 17 Patrons 18 Trustees 19 Looking ahead 20 ANNUAL REVIEW 2019 • 2 A word from the Chief Executive My first year as Langdon’s Chief Executive has been one of listening, learning and understanding. It has been a year in which we have been able to focus the organisation’s mission and purpose and to embark upon a process in which we can develop a new five-year strategy that all our stakeholders can support. As a parent of a daughter with a severe learning disability, I know only too well the essential role that organisations such as Langdon play in the lives of members and their families and the challenge of working against the low expectations that society has of people with learning disabilities and those with autistic spectrum disorders. We aspire to provide a ‘greenhouse’ for our members, in which our members, rather than a ‘warehouse’ in which it is too easy to see care as a need in itself rather than a means to much more positive outcomes. Our staff are the most important asset of the organisation and the past year has demonstrated the significant amount of work we have to do to equip them to have the depth of skills and knowledge required to meet our members’ needs. -

British Synagogue Membership in 1990

BRITISH SYNAGOGUE MEMBERSHIP IN 1990 MARLENA SCHMOOL ii '1,' FRANCES COHEN COMMUNITY RESEARCH UNIT BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ---------~_.,...,..~-----:=,~'; ------~----~---~-------- -~-~------- - 'li1 r ·~~', :r CONTENTS Community Research Unit Board of Deputies of British Jews Preface 2 Overview 3 Key to Abbreviations in Listings 5 The Board of Deputies, founded in 1760, is the representative body of British Jewry. The Community Research Unit was established in 1965 following a conference on 'Jewish Life in Modern Britain' which the Board convened in 1962 in association with the Institute of Section 1 United Kingdom Membership Contemporary Jewry of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. The Unit compiles statistical data on various aspects of the community, prepares Map 1 Standard Regions of the United Kingdom 6 interpretive studies of social and demographic trends and acts as a resource centre for scholars, planners and communal organisations. Table 1.1 Aggregate Synagogue Membership by Standard Region 7 Table 1.2 Aggregate Household Membership by Synagogal Grouping 8 Listing 1 Individual Congregational Membership by Standard Region 9 Section 2 Greater London Membership Map 2 Greater London and environs 14 Table 2 Aggregate Synagogue Membership by London Borough 15 Listing 2 Individual Congregational Membership by London Borough 16 Section 3 Patterns in Synagogue Membership, 1970-90 21 Regional Change Male Membership Synagogal Groups Appendix 27 © 1991 Board of Deputies of British Jews ISBN 0 90710412 6 - 1 - PREFACE OVERVIEW This listing is the third prepared by the Community Research Unit of the Board of Deputies This booklet provides details of synagogue membership in the United Kingdom in 1990. following compilations for 1977 and 1983. -

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

Kol Kehillat Kernow 06 09.FH11

KolKol KehillatKehillat KernowKernow Voice of the Jewish community in Cornwall Issue 15 kehillatkernow.com Elul 5766/September 2006 Summer visitors: liturgy, lecture and Limmud Harvey Kurzfield Elkan Levy, co-director of the United Synagogue Office for Small Communities, together with his wife Celia, visited our community for the weekend of 22nd July 2006. Elkan conducted the Friday night service at Milton & Glorias Harvey Kurzfield and Elkan Levy admiring the ark. This was donated by Estelle Moses, who house using the liturgy from the Singer prayer had it made up by a cabinet-maker to a design by Anne Hearle. Anne also added the Hebrew inscription, which translates as Open my heart to wisdom and understanding and made book, reawakening many memories for those the curtains which depict the stone tablets. brought up in the Orthodox tradition. Elkans enthusiasm really engaged those present and On Sunday, Elkan delivered our annual lecture book shop which elicited a great deal of interest the service was enjoyed by all. Members were at Carnon Downs Village Hall. Leslie had and generated excellent sales. also presented with copies of the The Song submitted a notice of this event to the Coracle, Elkan delivered his lecture, Cromwell and the and Spirit of Shabbat CD, a booklet for the Truro Cathedrals newsletter to all churches in rabbi with a terrific sense of drama so that Grace after Meals service and a What Will Cornwall, and this brought a welcome influx you almost felt as if you were viewing events You Do? booklet subtitled 48 things you can of visitors to the event. -

(A Company Limited by Guarantee) Trustees‟ Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 March 2016

Norwood Ravenswood (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Trustees‟ Annual Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31 March 2016 Registered Charity Number: 1059060 Registered Company Number: 03263519 Contents Page Charity Information………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Trustees‟ Annual Report: ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4-16 Objectives and Activities …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Structure, Governance and Management ………………………………………………………………….. 5 Strategic Report: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 10 - 16 Strategic Priorities ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Achievements and Performance ………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Financial Review ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Plans for Future Periods …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 13 Principal Risks and Uncertainties………………………………………………………………………………… 14 Independent Auditor‟s Report …………………………………………………………………………………………. 17 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities ………………………………………………………………… 18 Consolidated Balance Sheet ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 19 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows …………………………………………………………………………. 20 Notes to the Financial Statements …………………………………………………………………………………. 21-45 2 Norwood Ravenswood – for the year ended 31 March 2016 CHARITY INFORMATION Patron HM The Queen Patron of Children‟s‟ Services Cherie Blair Patron of Adults‟ Services Norma Brier Patron of Volunteering Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis Presidents Lord Jon Mendelsohn (appointed 16 Nov 2015) Lady Nicola Mendelsohn CBE (appointed 16 Nov -

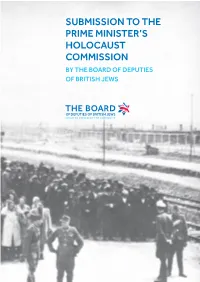

Submission to the Prime Minister's Holocaust

SUBMISSION TO THE PRIME MINISTER’S HOLOCAUST COMMISSION BY THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Our starting point 2 2. Jewish perspectives & Recommendations 3 3. Education 7 4. Commemorative events, Memorials & Museums 10 5. How to preserve survivor testimony for future generations 13 6. Other issues 14 7. In conclusion 15 Appendix 1 – Our consultation 16 Appendix 2 – Holocaust Memorial Day: Statement of Commitment 17 Front cover image courtesy of The Wiener Library Designed by Graphical - www.graphicalagency.com 1 SUBMISSION TO THE PRIME MINISTER’S HOLOCAUST COMMISSION INTRODUCTION The Board of Deputies of British Jews, set up in 1760, is the recognised voice of the Jewish Community in Britain. It exists to promote and defend the religious and civil liberties of British Jewry and to promote its standing. Nearly 300 Deputies represent local communities and organisations in a democratically elected body ZKLFKLVWKHƪUVWSRUWRIFDOOIRUJRYHUQPHQWDQGRWKHUIDLWKJURXSVRQLVVXHV relating to the Jewish community. On issues of importance, such as Holocaust remembrance and education, the Board reaches out through its Deputies and its close relationship with the other organisations to the whole community to consult and to listen, ensuring that we speak with a strong and consistent voice. Most of the community’s major communal organisations have contributed to this document and are listed in Appendix 1, along with details of our consultation process. Many are also submitting their own documents. We particularly urge the Commission to consider, alongside this document, submissions from the main synagogal bodies, the Regional Representative Councils, the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities, and of course, the Charedi community, each of which bring a particular perspective.