Profile Final Draft of Nri.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igneous Processes During the Assembly and Breakup of Pangaea: Northern New Jersey and New York City

IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 At the College of Staten Island, Staten Island, NY IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND, STATEN ISLAND, NY i GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY 2012/2013 EXECUTIVE BOARD President .................................................. Alan I. Benimoff, PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY Past President ............................................... Jane Alexander PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY President Elect ............................... Nurdan S. Duzgoren-Aydin, PhD., New Jersey City University Recording Secretary ..................... Stephen J Urbanik, NJ Department of Environmental Protection Membership Secretary ..............................................Suzanne Macaoay Ferguson, Sadat Associates Treasurer ............................................... Emma C Rainforth, PhD., Ramapo College of New Jersey Councilor at Large………………………………..Alan Uminski Environmental Restoration, LLC Councilor at Large ............................................................ Pierre Lacombe, U.S. Geological Survey Councilor at Large ................................. -

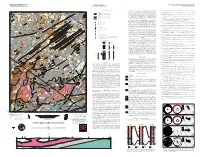

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Monmouth Junction Quadrangle, Water Resources Management U.S

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONMOUTH JUNCTION QUADRANGLE, WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOMERSET, MIDDLESEX, AND MERCER COUNTIES, NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES GMS 18-4 Cedar EXPLANATION OF MAP SYMBOLS cycle; lake level rises creating a stable deep lake environment followed by a fall in water level leading to complete Cardozo, N., and Allmendinger, R. W., 2013, Spherical projections with OSXStereonet: Computers & Geosciences, v. 51, p. 193 - 205, doi: 74°37'30" 35' Hill Cem 32'30" 74°30' 5 000m 5 5 desiccation of the lake. Within the Passaic Formation, organic-rick black and gray beds mark the deep lake 10.1016/j.cageo.2012.07.021. 32 E 33 34 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 490 000 FEET 542 40°30' 40°30' period, purple beds mark a shallower, slightly less organic-rich lake, and red beds mark a shallow oxygenated 6 Contacts 100 M Mettler lake in which most organic matter was oxidized. Olsen and others (1996) described the next longer cycle as the Christopher, R. A., 1979, Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New 6 A 100 I 10 N Identity and existance certain, location accurate short modulating cycle, which is made up of five Van Houten cycles. The still longer in duration McLaughlin cycles Jersey: Palynology, v. 3, p. 73-121. S T 44 000m MWEL L RD 0 contain four short modulating cycles or 20 Van Houten cycles (figure 1). -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Spring 2021 Newsletter

Spring | 2021 New Jersey Conservation FINDING PEACE in the PANDEMIC Getting outdoors for body and mind PIPELINE CASE HEADS TO U.S. SUPREME COURT 10 High court will decide if private PennEast company can seize public lands to build a for‐profit pipeline. SOMEWHERE, OVER THE RAINBOW 12 Rainbow Hill at Sourland Mountain Preserve offers sweeping views, including rainbows after storms! TEN MILE TRAIL VISION REALIZED 14 Newly‐preserved land helps connect 1,200 acres of open space and farmland in Hunterdon County. ABOUT THE COVER “During the pandemic this past year, being outdoors in natural surroundings simply felt nice, sane, and free.” MaryAnn Ragone DeLambily took this stunning photo while hiking through Franklin Parker Preserve, one of the many places New Jerseyans found solace over the past year. Trustees Rosina B. Dixon, M.D. HONORARY TRUSTEES PRESIDENT Hon. James J. Florio Wendy Mager FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Thomas H. Kean Joseph Lemond Hon. Maureen Ogden SECOND VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Christine Todd Whitman Finn Caspersen, Jr. TREASURER From Our Pamela P. Hirsch SECRETARY Executive Director ADVISORY COUNCIL Penelope Ayers ASSISTANT SECRETARY Bradley M. Campbell Michele S. Byers Cecilia Xie Birge Christopher J. Daggett Jennifer Bryson Wilma Frey Roger Byrom John D. Hatch Theodore Chase, Jr. Douglas H. Haynes It seems like we all need inspiration and hope this year given the not‐over‐yet pandemic, Jack Cimprich H. R. Hegener David Cronheim Hon. Rush D. Holt climate change, species extinction, tribalism, isolation and the news! Getting outdoors is one John L. Dana Susan L. Hullin way to find “Peace in the Pandemic” as you can read about in the pages that follow. -

2020 Natural Resources Inventory

2020 NATURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY TOWNSHIP OF MONTGOMERY SOMERSET COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared By: Tara Kenyon, AICP/PP Principal NJ License #33L100631400 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 5 AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN AND AROUND MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP ...................................................... 7 REGULATIONS AND PROGRAMS RELATED TO AGRICULTURE ...................................................................... 11 HEALTH IMPACTS OF AGRICULTURAL AVAILABILITY AND LOSS TO HUMANS, PLANTS AND ANIMALS .... 14 HOW IS MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP WORKING TO SUSTAIN AND ENHANCE AGRICULTURE? ................... 16 RECOMMENDATIONS AND POTENTIAL PROJECTS .......................................................................................... 18 CITATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 19 AIR QUALITY .............................................................................................................................................................. 21 CHARACTERISTICS OF AIR .................................................................................................................................. 21 -

Land, Natural Resources, and Geology

Land and Natural Resources of West Amwell By Fred Bowers, Ph.D Goat Hill from the north Diabase Boulders are common. Shale and Argillite outcrops appear like this. General Description of the Area West Amwell Township is in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, USA. It is a 22 square mile rural township with just over 2200 people, located near Lambertville, New Jersey. It is one of the more scenic parts of the New Jersey Piedmont. It is identified in red on the maps below. West Amwell is characterized by most people as a "rocky land." One of the oldest villages in the township is called Rocktown. If you visit or look around the township, you cannot avoid seeing rocks and outcrops like those pictured above. Hunterdon County New Jersey, with West Amwell located at the southern border, marked in red The physiographic provinces of New Jersey, with Hunterdon County and West Amwell marked in red Rocks The backbone of West Amwell Township's land is the Sourland Mountain; a typical Piedmont ridge formed by a very hard igneous rock called diabase or "Trap Rock." The Sourland Mountain ends at the Delaware River below Goat Hill which you see in the picture above, looking south from the Lambertville toll bridge. To the south and north of the diabase, shale and argillite occurs, and these rocks form the lower lands we know of as Pleasant Valley and the shale ridges and valleys you see from around Mt. Airy. In order to appreciate the rocks and the influence they have on the look of the land, it is useful to have a short review of rocks. -

Hiking Trail Reference Guide

1. Hunterdon County SUMMARY OF RULES AND REGULATIONS Arboretum County Reference Map 2. Charlestown Reserve The rules and regulations governing use of facilities or properties administered by the Hiking Trail Hunterdon County Division of Parks and Recreation are promulgated in accordance with provisions of the N.J. Statutes Title 40:32-7.12, which reads as follows: 3. Clover Hill Park With the exception of park "The Board of Chosen Freeholders may by resolution make, alter, amend, and properties with reservable facilities, 4. Cold Brook Reserve repeal rules and regulations for the supervision, regulation and control of all activities carried on, conducted, sponsored, arranged, or provided for in all properties are “carry in / carry 5. Columbia Trail connection with a public golf course or other county recreational, playground, Reference out” and trash/recycling receptacles or public entertainment facility, and for the protection of property, and may 6. Court Street Park prescribe and enforce fines and penalties for the violation of any such rule or are not provided. Please plan regulation.” 7. Crystal Springs Preserve accordingly and do not leave any 8. Cushetunk Mountain These rules and regulations have been promulgated for the protection of trash/recyclables behind. our patrons and for the facilities and natural resources administered by the Guide Preserve Hunterdon County Division of Parks and Recreation. Permits: A fully executed Facility Use Permit, issued by the County of 9. Deer Path Park & Round Hunterdon for any activity, shall authorize the activity only insofar as it may be performed in strict accordance with the terms and conditions Mountain Section thereof. -

Hikes Are Scheduled for Almost Every Saturday, Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday

Hunterdon Hiking Club Organized 1980 Affiliate of the Hunterdon County Department of Parks and Recreation FALL 2015 NEWSLETTER SEPTEMBER – OCTOBER - NOVEMBER HHC Web Page: www.HunterdonHikingClub.org ______________________________________________________ Hunterdon Hiking Club C/O Hunterdon County Dept of Parks & Recreation PO Box 2900 Flemington, NJ 08822-2900 PUBLIC VERSION-----Note: this version of the newsletter does not contain hike meeting times/contact phone #s Non club members should contact Bill Claus 908-788-1843or Lynn Burtis 908-782-6428 for more information before joining a hike FIRST CLASS MAIL GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE HUNTERDON HIKING CLUB Who we are! The Hunterdon Hiking Club (HHC) is an affiliated organization of the Hunterdon County Parks System. The purpose of the club is to provide a forum where individuals may join with others for the personal enjoyment of hiking and other outdoor activities. What do we do? Hikes are scheduled for almost every Saturday, Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. Bicycle rides are scheduled on Tuesdays and Fridays in season and shorter hikes are scheduled for Tuesdays. Canoe/kayak trips and X-country skiing are often scheduled as the weather permits. Weekday trips combining a city walk plus a visit to a museum are occasionally scheduled. HHC General Membership Meetings HHC meetings are the second Thursday of the month, at the Parks Office: 1020 Highway 31, Lebanon, NJ 08833 www.co.hunterdon.nj.us/depts/parks/parks.htm. The meetings start at 7pm. (No meetings in July, August & December). Hunterdon Hiking Club Officers - June 2015 – May 2016 President: Bill Claus 908-788-1843 Secretary: Nardi B. -

2017-2019 Historical, Geological, and Photographic Perspectives on Some Old Cairns Atop Cushetunk Mountain in Hunterdon County, New Jersey

Field research report, funded in part by RVCC Adjunct Faculty Research Grant AY 2018-2019. 2017-2019 historical, geological, and photographic perspectives on some old cairns atop Cushetunk Mountain in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, February 2019 Gregory C. Herman, PhD, Adjunct Professor of Geology Raritan Valley Community College Branchburg New Jersey With field assistance from J. Mark Zdepski, Benjamin Brandner, Jacob Buxton, and Raymond Simonds. 1 Field research report, funded in part by RVCC Adjunct Faculty Research Grant AY 2018-2019. Introduction In late 2016 I began donating time to the Hunterdon County Historical Society by photographing and helping document their collection of American Indian artifacts amassed by Hiram E. Deats and John C. Thatcher in the late 1800s 1. This research of native peoples in Hunterdon County led soon after to the rediscovery of some ancient man-made stone mounds, or cairns of suspected Indian origin located atop Cushetunk Mountain (fig. 1). The site is off the beaten path and described in James Snell’s The History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey (Snell, 1881). A 1984 article in the N.Y. Times titled Searchers Seek Indian Crypt refers to Snell’s work and recent efforts on locating them. This report chronicles the rediscovery of these cairns in a setting that is congruent with legendary colonial accounts and sets the stage for subsequent archeological work. A brief accounting of how I read about and acted upon finding the cairns is summarized together with the results of repeated excursions to the site to characterize their occurrence and evaluate this site with respect to a reported mountaintop fortress of the Raritan Tribe of American Indians in the 17 th century. -

Hofstra University 014F Field Guidebook Geology of the Palisades and Newark Basin, Nj

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY 014F FIELD GUIDEBOOK GEOLOGY OF THE PALISADES AND NEWARK BASIN, NJ 18 October 2008 Figure 1 – Physiographic diagram of NY Metropolitan area with cutaway slice showing structure. (From E. Raisz.) Field Trip Notes by: Charles Merguerian © 2008 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 4 PHYSIOGRAPHIC SETTING................................................................................................... 4 BEDROCK UNITS..................................................................................................................... 7 Layers I and II: Pre-Newark Complex of Paleozoic- and Older Rocks.................................. 8 Layer V: Newark Strata and the Palisades Intrusive Sheet.................................................. 12 General Geologic Relationships ....................................................................................... 12 Stratigraphic Relationships ............................................................................................... 13 Paleogeographic Relationships ......................................................................................... 16 Some Relationships Between Water and Sediment......................................................... -

Settings Report for the Central Delaware Tributaries Watershed Management Area 11

Settings Report for the Central Delaware Tributaries Watershed Management Area 11 02 03 05 01 04 06 07 08 11 09 10 12 20 19 18 13 14 17 15 16 Prepared by: The Regional Planning Partnership Prepared for: NJDEP October 15, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v List of Tables vi Acknowledgements vii 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Importance of Watershed Planning 1 3.0 Significance of the Central Delaware Tributaries 2 4.0 Physical and Ecological Characteristics 4.1 Location 2 4.2 Physiography and Soils 3 4.3 Surface Water Hydrology 4 4.3.1 Hakihokake/Harihokake/Nishisakawick Creeks 5 4.3.2 Lockatong/Wickecheoke Watershed 6 4.3.3 Alexauken/Moores/Jacobs Watershed 6 4.3.4 Assunpink Creek Above Shipetaukin Creek 7 4.3.5 Assunpink Below Shipetaukin Creek 7 4.4 Land Use/Land Cover 9 4.4.1 Agricultural Land 9 4.4.2 Forest Land 11 4.4.3 Urban and Built Land 12 4.4.4 Wetlands 12 4.4.5 Water 14 4.4.6 Barren Lands 14 4.5 Natural Resource Priority Habitat 14 5.0 Surface Water Quality 5.1 Significance of Streams and Their Corridors 15 5.2 Federal Clean Water Act Requirements for Water Quality in New Jersey 15 5.3 Surface Water Quality Standards 16 5.4 Surface Water Quality Monitoring 18 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 5.4.1 Monitoring Stations in the Central Delaware Tributaries 18 5.5 Surface Water Quality in the Hakihokake/Harihokake/ Nishisakawick 5.5.1 Chemical and Sanitary Water Quality 19 5.5.2 Biological Evaluation 19 5.6 Surface Water Quality in the Lockatong/Wickecheoke Watershed 5.6.1 Chemical and Sanitary Water Quality 20 5.6.2 Biological Evaluation 20 5.7 -

Cushetunk Mountain Preserve

Cushetunk Mountain Preserve Cushetunk Mountain Preserve Round Valley Recreation Area Cushetunk Mountain Cushetunk Mountain Preserve is part of a Location: Cushetunk Mountain Preserve spans Access to the Round Valley Recreation Area horseshoe-shaped mountain that was formed across the border of Clinton and Readington is prohibited from the Cushetunk Mountain Preserve by volcanic activity during the Triassic Period Townships. The parking area is located at 106 Nature Preserve. For information about 200 million years ago. The Lenni Lenape Old Mountain Road, Lebanon 08833. This park Round Valley, contact their office at (908) 236 Trail Map and Guide called this area “Cushetunk,” meaning “place is open from sunrise to sunset. Please note that -6355. of hogs,” due to the settlers’ hogs who at times there are no restroom facilities at this park. escaped and roamed the mountains. Settlers Wildlife & Habitat Directions from the Clinton Area: simply called the area “Hog Mountain.” The preserve resides on the northern side of Take I-78 east to Route 22 east. On Route 22, travel until the junction with Route 629. The the Cushetunk Mountain. Since it is out of direct sunlight, the habitat is wetter then the junction is at a traffic light and marked by a sign for Round Valley. Turn right on Route 629 and southern side. Trees in in the park include proceed for about 0.5 miles until a left-hand turn chestnut oaks, tulip trees, beeches, and for the “Boat-Launching Ramp.” Turn left and hickories. A variety of woodland birds can be follow the road for another 1.4 miles to Old seen or heard throughout the park, including Mountain Road.