The First 300 Years of Hunterdon County 1714 to 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

The Magazine of Memphis University School • Winter 2003-04 Hheadmaster’Seadmaster’S Mmessageessage by Ellis Haguewood

The Magazine of Memphis University School • Winter 2003-04 HHeadmaster’seadmaster’s MMessageessage by Ellis Haguewood What if Maine encumber my friends at other schools, and I don’t feel as if someone is always looking over my shoulder in the classroom. Has Nothing to Say I have colleagues who support me, the school doesn’t often schedule activities that interfere with my class time, and my to Texas? students treat me with respect.” All good teachers want to teach in a school that honors Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys, which distract our attention teaching, offers a solid academic program, and exercises the from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end independence to do what is right, not just what is expedient. ....We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Good teachers want a school that teaches respect for authority, Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to respect for one another, and respect for property. Good teachers communicate. Either is in such a predicament as the man who was earnest want a school that encourages teachers and students to interact to be introduced to a distinguished deaf woman, but when he was outside the classroom. Most of all, good teachers want a school presented, and one end of her ear trumpet was put into his hand, had that refuses to substitute fads for the hard work of teaching students. MUS is such a school. nothing to say. Walden, Henry David Thoreau The true test of any school is not how many computers it has, how many sports it offers, to which educational guru it Each year before we send out contracts to current teachers kowtows this month, or what educational buzzwords it can for the next school year, I like to offer them the opportunity to throw around. -

Tribute to Champions

HLETIC C AT OM M A IS M S O I C O A N T Tribute to Champions May 30th, 2019 McGavick Conference Center, Lakewood, WA FEATURING CONNELLY LAW OFFICES EXCELLENCE IN OFFICIATING AWARD • Boys Basketball–Mike Stephenson • Girls Basketball–Hiram “BJ” Aea • Football–Joe Horn • Soccer–Larry Baughman • Softball–Scott Buser • Volleyball–Peter Thomas • Wrestling–Chris Brayton FROSTY WESTERING EXCELLENCE IN COACHING AWARD Patty Ley, Cross Country Coach, Gig Harbor HS Paul Souza, Softball & Volleyball Coach, Washington HS FIRST FAMILY OF SPORTS AWARD The McPhee Family—Bill and Georgia (parents) and children Kathy, Diane, Scott, Colleen, Brad, Mark, Maureen, Bryce and Jim DOUG MCARTHUR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Willie Stewart, Retired Lincoln HS Principal Dan Watson, Retired Lincoln HS Track Coach DICK HANNULA MALE & FEMALE AMATEUR ATHLETE OF THE YEAR AWARD Jamie Lange, Basketball and Soccer, Sumner/Univ. of Puget Sound Kaleb McGary, Football, Fife/Univ. of Washington TACOMA-PIERCE COUNTY SPORTS HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES • Baseball–Tony Barron • Basketball–Jim Black, Jennifer Gray Reiter, Tim Kelly and Bob Niehl • Bowling–Mike Karch • Boxing–Emmett Linton, Jr. and Bobby Pasquale • Football–Singor Mobley • Karate–Steve Curran p • Media–Bruce Larson (photographer) • Snowboarding–Liz Daley • Swimming–Dennis Larsen • Track and Field–Pat Tyson and Joel Wingard • Wrestling–Kylee Bishop 1 2 The Tacoma Athletic Commission—Celebrating COMMITTEE and Supporting Students and Amateur Athletics Chairman ������������������������������Marc Blau for 76 years in Pierce -

Sousa Comes Marching Home the a Window for Freemasonry

THE A Window for Freemasonry Vol. 38 No. 3 AUGUST 2007 Sousa comes marching home THE A Window for Freemasonry AUGUST 2007 Volume 38 No. 3 Features 4 Driving Force 4 by Alan E. Foulds, 32° One man’s quest to honor John Philip Sousa. 8 What Makes A Mason by Robert M. Wolfarth, 32° Examples of Masonic acts that make a man a Mason. 8 16 The Ripple Effect 10 By the Way by Gina Cooke Reflections of a first year. by Aimee E. Newell Encountering Masonic signs along the road. Columns 10 3 Sovereign Grand Commander 18 Notes from the Scottish Rite Journal 19 Brothers on the Net 20 Scottish Rite Charities 21 The Stamp Act 22 Also: Book Nook 24 HealthWise 26 5 7 13 Views from the Past Bro. Force and His Band • The March King • Builder’s Council: New 14 14 28 Members – 2007 • How Are We Doing? • Walks for Children with Today’s Family 14 15 17 Dyslexia • Learning Centers in Operation • The Heritage Shop • 30 25 27 30 Readers Respond Masonic Word Math • Masonic Compact • Quick Quotes • Hiram 30 32 31 • On the Lighter Side • Scottish Rite Charities Et cetera, et cetera, etc. SUPREME COUNCIL, 33° EDITOR Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite Mailing Address: Alan E. Foulds, 32° Northern Masonic Jurisdiction, U.S.A. PO Box 519, Lexington, MA 02420-0519 SOVEREIGN GRAND COMMANDER PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS John Wm. McNaughton, 33° Sonja B. Faiola Editorial Office: Beth E. McSweeney THE NORTHERN LIGHT (ISSN 1088-4416) is published quarterly in February, May, 33 Marrett Road (Route 2A) MEDIA ADVISORY COMMITTEE August, and November by the Supreme Council, 33°, Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite, Lexington, Massachusetts 02421 Stephen E. -

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by B. F. Skinner William James Lectures Harvard

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by B. F. Skinner William James Lectures Harvard University 1948 To be published by Harvard University Press. Reproduced by permission of B. F. Skinner† Preface In 1930, the Harvard departments of psychology and philosophy began sponsoring an endowed lecture series in honor of William James and continued to do so at irregular intervals for nearly 60 years. By the time Skinner was invited to give the lectures in 1947, the prestige of the engagement had been established by such illustrious speakers as John Dewey, Wolfgang Köhler, Edward Thorndike, and Bertrand Russell, and there can be no doubt that Skinner was aware that his reputation would rest upon his performance. His lectures were evidently effective, for he was soon invited to join the faculty at Harvard, where he was to remain for the rest of his career. The text of those lectures, possibly somewhat edited and modified by Skinner after their delivery, was preserved as an unpublished manuscript, dated 1948, and is reproduced here. Skinner worked on his analysis of verbal behavior for 23 years, from 1934, when Alfred North Whitehead announced his doubt that behaviorism could account for verbal behavior, to 1957, when the book Verbal Behavior was finally published, but there are two extant documents that reveal intermediate stages of his analysis. In the first decade of this period, Skinner taught several courses on language, literature, and behavior at Clark University, the University of Minnesota, and elsewhere. According to his autobiography, he used notes from these classes as the foundation for a class he taught on verbal behavior in the summer of 1947 at Columbia University. -

The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time (The Frontiers Collection), 5Th

the frontiers collection the frontiers collection Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur M.P. Silverman J. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. InformationandItsRoleinNature The Thermodynamic By J. G. Roederer Machinery of Life By M. Kurzynski Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime By V. Petkov The Emerging Physics of Consciousness Quo Vadis Quantum Mechanics? Edited by J. A. Tuszynski Edited by A. C. Elitzur, S. Dolev, N. Kolenda Weak Links Life – As a Matter of Fat Stabilizers of Complex Systems The Emerging Science of Lipidomics from Proteins to Social Networks By O. G. Mouritsen By P. Csermely Quantum–Classical Analogies Mind, Matter and the Implicate Order By D. Dragoman and M. Dragoman By P.T.I. Pylkkänen Knowledge and the World Quantum Mechanics at the Crossroads Challenges Beyond the Science Wars New Perspectives from History, Edited by M. -

The Governors of New Jersey' Michael J

History Faculty Publications History Summer 2015 Governing New Jersey: Reflections on the Publication of a Revised and Expanded Edition of 'The Governors of New Jersey' Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael J. "Governing New Jersey: Reflections on the Publication of a Revised and Expanded Edition of 'The Governors of New Jersey.'" New Jersey Studies 1.1 (Summer 2015), 1-17. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/57 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Governing New Jersey: Reflections on the Publication of a Revised and Expanded Edition of 'The Governors of New Jersey' Abstract New Jersey’s chief executive enjoys more authority than any but a handful of governors in the United States. Historically speaking, however, New Jersey’s governors exercised less influence than met the eye. In the colonial period few proprietary or royal governors were able to make policy in the face of combative assemblies. The Revolutionary generation’s hostility to executive power contributed to a weak governor system that carried over into the 19th and 20th centuries, until the Constitution was thoroughly revised in 1947. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

1 SUMMER 2017 TASTERS GUILD JOURNAL from the President

1 SUMMER 2017 TASTERS GUILD JOURNAL From the President By Joe Borrello As of June 1, 2017 Tasters Guild has officially become affiliated with the American Wine Society, a 6,000 member non-profit organization based in Scranton, PA. This affiliation will give you the opportunity for additional wine and food educational experiences. There is no cost to you through your current membership expiration date. AWS has similar educational objectives as Tasters Guild and it sponsors a large, three CONTENTS: day informative wine conference for its membership. This conference is moved to different locations around the country in November of each year. My wife, Barb, and I attended the 4 The Red Blend Trend conference last November in California and participated in a number of excellent wine by Michael Schafer tasting seminars. Over 600 AWS members were in attendance. AWS also publishes an AWS Journal quarterly magazine and a newsletter which will be distributed to Tasters Guild 5 Historical Old Vine members either electronically or in a printed copy. Zinfandel All Tasters Guild members in good standing as of July 1, 2017 will receive a by A. Brian Cain complimentary membership to AWS through at least December of 2017 or until their current Tasters Guild membership expires. You will be eligible for all the benefits of both 6-7 The Retailer's Shelf organizations. by Dick Scheer Village Corner You Remain a Tasters Guild Member Tasters Guild chapters will retain their individual 8 Browning of Food II identity as well as an affiliation with the American by David Theiste, PhD Wine Society and will continue to hold local events for their members as they have always 9 Ask Tasters Guild been doing. -

Minutes of the Close of the Event

Hunterdon County Agriculture Development Board Meeting Special Meeting March 29, 2021 @ 7:30 pm 314 Route 12 County Complex Building #1 | Assembly Room Flemington, New Jersey Members in Attendance: CADB Staff Present: Dave Bond-Chair Shana Taylor, Esq. County Counsel Bob Hoffman-Vice Chair Aaron Culton, Esq., Asst County Counsel Christian Bench Bob Hornby, CADB Administrator Susan Blew Megan Muehlbauer - NJAES Ted Harwick Kevin Milz – Soil Cons. Dist. David Kyle John Perehinys Liz Schmid In consideration of COVID-19 public health guidelines, this meeting was held telephonically and via Zoom and hosted by County Counsel Paralegal Samantha Gravel. CADB members and the public called in to a prearranged number or Zoom login advertised on the agenda distributed and posted electronically. There is an option of attending telephonically at 1 (646) 558-8656 Meeting ID: 854 0349 4017. When prompted for a passcode, enter 444103 then press #. Out of consideration for others, please mute your phone unless you are speaking. Please contact Bob Hornby at [email protected] or (908) 788-1490 with any questions or concerns Open Public Meeting Act: Chairman Dave Bond opened the meeting at 7:30 p.m. and read the Open Public Meeting Act: "This meeting is being held in accordance with the provisions of the Open Public Meeting Act. Adequate notice has been provided by prominently posting on the first floor of the County Administration Building, Main St., Flemington, and by faxing on or before March 19, 2021, to The Hunterdon Democrat, The Star Ledger, The Trenton Times, The Courier News, The Express Times, and TAPInto newspapers designated by the Hunterdon County Agriculture Development Board to receive such notices, and by filing with the Hunterdon County Clerk.." Pledge of Allegiance: Roll Call: Absent – Forest Locandro, Gerry Lyness and Marc Phillips Right To Farm Matters: • SSAMP Hearing - o Beneduce Vineyards (Alexandria Block 21 Lot 41.31) – County Counsel, Aaron Culton asked the board for a MOTION to re-open the Public Hearing on Beneduce Vineyards. -

Deli, Keyport Army & Navy, Collectors OPEN 7 DAYS-11:00 AM Until 2 AM Tificates at Participating Merchants

IN THIS ISSUE IN THE NEWS A u g u s t T . SERVING ABERDEEN, HAZLET, HOLMDEL, r e m e m b e r e d KEYPORT, MATAWAN AND MIDDLETOWN Page 18 P a g e 9 FEBRUARY 5, 1997 40 CENTS VOLUME 27, NUMBER 6 C o p s t u d y r e a d y f o r u n v e i l i n g Recom m endation is to cut force; chief prefers to increase ranks to 101 BY CINDY HERRSCHAFT Staff W riter ecommendations made by Deloitte Touche, Parsippany, about the Middletown Police Department will R finally see the light of day. Local officials are expected to release the in-depth analysis during a press confer ence at town hall tomorrow at noon. Among the recommendations made by the accounting firm are a 10 percent reduc tion in force, hiring more civilians and eliminating the position of captain entirely, according to the study. However, local officials have stressed that no decision has been reached about the department’s future. The in-depth analysis, completed in November, is still under First-graders at Cliffwood School in Aberdeen participate in a parade of fans last week, showing off the Japanese fans they made as part of a Reading Around the review . World program. At right, sixth-grader Nicole Robles shows off her handmade fan. “It’s a different opinion than what For more about the program, see page 20. we’ve been hearing,” Mayor Raymond (Jackie Pollack/Greater Media) O’Grady said. “They call for a lot less offi cers with very factual information that backs that up.” The police department, however, re quested funding in the 1997 budget to hire Target store aim s for M id’tow n another 10 officers to raise the number of officers to 101. -

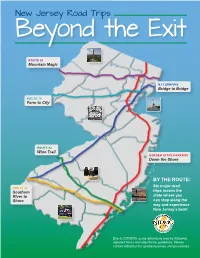

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades.