2020 Natural Resources Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igneous Processes During the Assembly and Breakup of Pangaea: Northern New Jersey and New York City

IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 At the College of Staten Island, Staten Island, NY IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND, STATEN ISLAND, NY i GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY 2012/2013 EXECUTIVE BOARD President .................................................. Alan I. Benimoff, PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY Past President ............................................... Jane Alexander PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY President Elect ............................... Nurdan S. Duzgoren-Aydin, PhD., New Jersey City University Recording Secretary ..................... Stephen J Urbanik, NJ Department of Environmental Protection Membership Secretary ..............................................Suzanne Macaoay Ferguson, Sadat Associates Treasurer ............................................... Emma C Rainforth, PhD., Ramapo College of New Jersey Councilor at Large………………………………..Alan Uminski Environmental Restoration, LLC Councilor at Large ............................................................ Pierre Lacombe, U.S. Geological Survey Councilor at Large ................................. -

Potential On-Shore and Off-Shore Reservoirs for CO2 Sequestration in Central Atlantic Magmatic Province Basalts

Potential on-shore and off-shore reservoirs for CO2 sequestration in Central Atlantic magmatic province basalts David S. Goldberga, Dennis V. Kenta,b,1, and Paul E. Olsena aLamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, 61 Route 9W, Palisades, NY 10964; and bEarth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854. Contributed by Dennis V. Kent, November 30, 2009 (sent for review October 16, 2009) Identifying locations for secure sequestration of CO2 in geological seafloor (16) may offer potential solutions to these additional formations is one of our most pressing global scientific problems. issues that are more problematic on land. Deep-sea aquifers Injection into basalt formations provides unique and significant are fully saturated with seawater and typically capped by imper- advantages over other potential geological storage options, includ- meable sediments. The likelihood of postinjection leakage of ing large potential storage volumes and permanent fixation of car- CO2 to the seafloor is therefore low, reducing the potential bon by mineralization. The Central Atlantic Magmatic Prov- impact on natural and human ecosystems (8). Long after CO2 ince basalt flows along the eastern seaboard of the United States injection, the consequences of laterally displaced formation water may provide large and secure storage reservoirs both onshore and to distant locations and ultimately into the ocean, whether by offshore. Sites in the South Georgia basin, the New York Bight engineered or natural outflow systems, are benign. For more than basin, and the Sandy Hook basin offer promising basalt-hosted a decade, subseabed CO2 sequestration has been successfully reservoirs with considerable potential for CO2 sequestration due conducted at >600 m depth in the Utsira Formation as part of to their proximity to major metropolitan centers, and thus to large the Norweigan Sleipner project (17). -

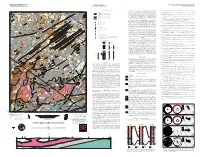

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Monmouth Junction Quadrangle, Water Resources Management U.S

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONMOUTH JUNCTION QUADRANGLE, WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOMERSET, MIDDLESEX, AND MERCER COUNTIES, NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES GMS 18-4 Cedar EXPLANATION OF MAP SYMBOLS cycle; lake level rises creating a stable deep lake environment followed by a fall in water level leading to complete Cardozo, N., and Allmendinger, R. W., 2013, Spherical projections with OSXStereonet: Computers & Geosciences, v. 51, p. 193 - 205, doi: 74°37'30" 35' Hill Cem 32'30" 74°30' 5 000m 5 5 desiccation of the lake. Within the Passaic Formation, organic-rick black and gray beds mark the deep lake 10.1016/j.cageo.2012.07.021. 32 E 33 34 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 490 000 FEET 542 40°30' 40°30' period, purple beds mark a shallower, slightly less organic-rich lake, and red beds mark a shallow oxygenated 6 Contacts 100 M Mettler lake in which most organic matter was oxidized. Olsen and others (1996) described the next longer cycle as the Christopher, R. A., 1979, Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New 6 A 100 I 10 N Identity and existance certain, location accurate short modulating cycle, which is made up of five Van Houten cycles. The still longer in duration McLaughlin cycles Jersey: Palynology, v. 3, p. 73-121. S T 44 000m MWEL L RD 0 contain four short modulating cycles or 20 Van Houten cycles (figure 1). -

Mnemonics Layout

NON- ESSENTIAL MNEMONICS AN UNNECESSARY JOURNEY INTO SENSELESS KNOWLEDGE KENT WOODYARD ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARK DOWNEY NON- ESSENTIAL MNEMONICS AN UNNECESSARY JOURNEY INTO SENSELESS KNOWLEDGE KENT WOODYARD ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARK DOWNEY Copyright © 2014 by Kent Woodyard Illustrations © 2014 by Mark Downey All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Prospect Park Books www.prospectparkbooks.com Distributed by Consortium Books Sales & Distribution www.cbsd.com Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data is on le with the Library of Congress. The following is for reference only: Woodyard, Kent Non-essential mnemonics: an unnecessary journey into senseless knowledge / by Kent Woodyard — 1st ed. ISBN: 978-1-938849-29-9 1. American wit and humor. 2. Mnemonic devices. I. Title. Design & layout by Renee Nakagawa To my friends. You know who you are. Disclaimer This is a work of ction. The data sets included are true and (predominantly) accurate, but all other elements of the book are utter nonsense and should be regarded as such. At no point was “research” or anything approaching an academic process employed during the writing of the mnemonic descriptions or prose portions of this book. Any quotations, historical descriptions, or autobiographical details bearing any resemblance to realities in the world around -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

THE JOURNAL of GEOLOGY March 1990

VOLUME 98 NUMBER 2 THE JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY March 1990 QUANTITATIVE FILLING MODEL FOR CONTINENTAL EXTENSIONAL BASINS WITH APPLICATIONS TO EARLY MESOZOIC RIFTS OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA' ROY W. SCHLISCHE AND PAUL E. OLSEN Department of Geological Sciences and Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964 ABSTRACT In many half-graben, strata progressively onlap the hanging wall block of the basins, indicating that both the basins and their depositional surface areas were growing in size through time. Based on these con- straints, we have constructed a quantitative model for the stratigraphic evolution of extensional basins with the simplifying assumptions of constant volume input of sediments and water per unit time, as well as a uniform subsidence rate and a fixed outlet level. The model predicts (1) a transition from fluvial to lacustrine deposition, (2) systematically decreasing accumulation rates in lacustrine strata, and (3) a rapid increase in lake depth after the onset of lacustrine deposition, followed by a systematic decrease. When parameterized for the early Mesozoic basins of eastern North America, the model's predictions match trends observed in late Triassic-age rocks. Significant deviations from the model's predictions occur in Early Jurassic-age strata, in which markedly higher accumulation rates and greater lake depths point to an increased extension rate that led to increased asymmetry in these half-graben. The model makes it possible to extract from the sedimentary record those events in the history of an extensional basin that are due solely to the filling of a basin growing in size through time and those that are due to changes in tectonics, climate, or sediment and water budgets. -

Spring 2021 Newsletter

Spring | 2021 New Jersey Conservation FINDING PEACE in the PANDEMIC Getting outdoors for body and mind PIPELINE CASE HEADS TO U.S. SUPREME COURT 10 High court will decide if private PennEast company can seize public lands to build a for‐profit pipeline. SOMEWHERE, OVER THE RAINBOW 12 Rainbow Hill at Sourland Mountain Preserve offers sweeping views, including rainbows after storms! TEN MILE TRAIL VISION REALIZED 14 Newly‐preserved land helps connect 1,200 acres of open space and farmland in Hunterdon County. ABOUT THE COVER “During the pandemic this past year, being outdoors in natural surroundings simply felt nice, sane, and free.” MaryAnn Ragone DeLambily took this stunning photo while hiking through Franklin Parker Preserve, one of the many places New Jerseyans found solace over the past year. Trustees Rosina B. Dixon, M.D. HONORARY TRUSTEES PRESIDENT Hon. James J. Florio Wendy Mager FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Thomas H. Kean Joseph Lemond Hon. Maureen Ogden SECOND VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Christine Todd Whitman Finn Caspersen, Jr. TREASURER From Our Pamela P. Hirsch SECRETARY Executive Director ADVISORY COUNCIL Penelope Ayers ASSISTANT SECRETARY Bradley M. Campbell Michele S. Byers Cecilia Xie Birge Christopher J. Daggett Jennifer Bryson Wilma Frey Roger Byrom John D. Hatch Theodore Chase, Jr. Douglas H. Haynes It seems like we all need inspiration and hope this year given the not‐over‐yet pandemic, Jack Cimprich H. R. Hegener David Cronheim Hon. Rush D. Holt climate change, species extinction, tribalism, isolation and the news! Getting outdoors is one John L. Dana Susan L. Hullin way to find “Peace in the Pandemic” as you can read about in the pages that follow. -

Curriculum Vitae June 2017

Curriculum Vitae June 2017 DAVID A. ROBINSON Department of Geography Phone: 848-445-4741 Office of the NJ State Climatologist Fax: 732-445-0006 Rutgers University Email: [email protected] 54 Joyce Kilmer Avenue Website (research): snowcover.org Piscataway, NJ 08854 Website (state climate): njclimate.org Contents Education ....................................................................................................................................1 Academic Appointments ..............................................................................................................1 Administrative Appointments .......................................................................................................2 Awards and Honors .....................................................................................................................2 Grants and Contracts ...................................................................................................................3 Publications .................................................................................................................................9 Professional Presentations ......................................................................................................... 49 Professional Activities ............................................................................................................... 67 Mentoring ................................................................................................................................ -

Hofstra University 014F Field Guidebook Geology of the Palisades and Newark Basin, Nj

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY 014F FIELD GUIDEBOOK GEOLOGY OF THE PALISADES AND NEWARK BASIN, NJ 18 October 2008 Figure 1 – Physiographic diagram of NY Metropolitan area with cutaway slice showing structure. (From E. Raisz.) Field Trip Notes by: Charles Merguerian © 2008 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 4 PHYSIOGRAPHIC SETTING................................................................................................... 4 BEDROCK UNITS..................................................................................................................... 7 Layers I and II: Pre-Newark Complex of Paleozoic- and Older Rocks.................................. 8 Layer V: Newark Strata and the Palisades Intrusive Sheet.................................................. 12 General Geologic Relationships ....................................................................................... 12 Stratigraphic Relationships ............................................................................................... 13 Paleogeographic Relationships ......................................................................................... 16 Some Relationships Between Water and Sediment......................................................... -

Final ERI Draft

Deptford Township Environmental Resource Inventory DRAFT April 2010 The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission is dedicated to uniting the region’s elected officials, planning professionals and the public with the common vision of making a great region even greater. Shaping the way we live, work and play, DVRPC builds consensus on improving transportation, promoting smart growth, protecting the environment, and enhancing the economy. We serve a diverse region of nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester and Mercer in New Jersey. DVRPC is the official Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Greater Philadelphia Region — leading the way to a better future. The symbol in our logo is adapted from the official DVRPC seal, and is designed as a stylized image of the Delaware Valley. The circular shape symbolizes the region as a whole. The diagonal line represents the Delaware River and the two adjoining crescents represent the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of New Jersey. DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding sources including federal grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey departments of transportation, as well as by DVRPC’s state and local member governments. The authors, however, are solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. DVRPC’s website may be translated into Spanish, Russian and Traditional Chinese online by visiting www.dvrpc.org. -

M U N Ic Ip a L S T O R M W a T E R M a N a G E M E N T P L a N E X Is T in G L a N D U S E /L a N D C O V

. Y E Y , S R D S A R T A E E T E I U D T N A J T T B N C O D N , A I O A W D E A H S G S C R E E I T . H S R N T I E I P S N H T S ’ R Y X S E D T M O F R D . A T E L I L R U E D F E E O Y L O W L E E H N A I S E O T E 02030105110080 S V P C T T A N B N U H T T O . E W E N L A E N A I C S E A N H S A I E I C P D D ’ H L S E U I R D N L E T M H D R R T O R T N S R E A H . R S D T PIKE RUN (ABOVE CRUSER BROOK) N U R E I T E T S S A I O E I I E O S S O E K A N I D R R W H S U . T W B E S : I N Y T T A W I E O E . C E E D S N I P F Y R . D H S N H E G A A L R O T H T E O S : C H A H F O Y B S E C N N S U S T M , E E O Y I S N , U T A D I O A S R E I E W S W N E S O D D Y T E R B S E R E I O U S R S R E I A U H P I R V E A B M J P T E R X F O D E S N A P P S E M O D F I E K O R W A T T A P E O T , E H E Y N S C D S W R M E G C C HILLSBOROUGH TOWNSHIP S H T N I E I S U E U 02030105030060 T O R T I N S P S L E Y I D A E I N L C A E T E E W N B H O B P P O SOMERSET COUNTY B L I R U T D O T R H I R P E MONTGOMERY D M S A P T O T F A P I NESHANIC RIVER (BELOW FNR / SNR CONFL) U N R E P E N H F D C I TOWNSHIP T F S P R R O P D R T O O C A I O A I E O L T A P A D O P P N T U W R S O I M Y T N E U C E E A O N T H A D Y I R H U S R M H S E D N L D R P . -

PSEG ESP Phase B Chapter 02 Site Characteristics Section 2.3 Meteorology

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................iii 2 SITE CHARACTERISTICS ............................................................................................. 2-1 2.3 Meteorology ........................................................................................................... 2-1 i LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.3-1 New Jersey Landform Areas (Reproduced from SSAR Figure 2.3-1) ................. 2-5 Figure 2.3-2 Local Topographic Map (Reproduced from SSAR Figure 2.3-2) ........................ 2-6 Figure 2.3-3 Locations and Categories of Regional Weather Monitoring Stations (Reproduced from SSAR Figure 2.3-11) ........................................................................................... 2-7 Figure 2.3-4 ASCE/SEI 7-05, Figure 6-1, "Basic Wind Speed" ............................................... 2-9 Figure 2.3-5 ASCE 7-05, "Figure 7-1: Ground Snow Loads, pg, for the United States (lb/ft2)” ................................................................................................ .2-14 Figure 2.3-6 Annual Mean Wind Rose at S/HC Primary Meteorological Tower 33-ft Level During 32 Year Period 1977-2008 (Reproduced from SSAR