Haiti Mission Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multilateral Peace Operations and the Challenges of Organized Crime

SIPRI Background Paper February 2018 MULTILATERAL PEACE PROJECT SUMMARY w The New Geopolitics of Peace OPERATIONS AND THE Operations III: Non‑traditional Security Challenges initiative CHALLENGES OF was launched with support from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, co‑sponsored ORGANIZED CRIME by Ethiopia, and in continued partnership with the Friedrich‑ jaÏr van der lijn Ebert‑Stiftung (FES). This phase of the initiative seeks to enhance understanding I. Introduction about peace operations and non‑traditional security Multilateral peace operations are increasingly confronting a set of challenges such as terrorism interrelated and mutually reinforcing security challenges that are relatively and violent extremism, new to them, that do not respect borders, and that have causes and effects irregular migration, piracy, which cut right across the international security, peacebuilding and organized crime and environmental degradation. It development agendas.1 Organized crime provides one of the most prominent aims to identify the various examples of these ‘non-traditional’ security challenges.2 perceptions, positions and There are many different definitions of organized crime depending on the interests of the relevant context, sector and organization. The United Nations Convention against stakeholders, as well as to Transnational Organized Crime defines an ‘organized criminal group’ as stimulate open dialogue, ‘a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time cooperation and mutual and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes understanding by engaging key or offences . in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other stakeholders and mapping the material benefit’.3 However, this definition is not unchallenged. -

MOE Steve Ijames

27-CR-20-12953 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 1/14/2021 1:33 PM Steve Ijames EDUCATION • Bachelor of Science degree in Criminal Justice Administration, Drury University, Springfield, Missouri • Master of Science Degree in Public Administration, City University, Bellevue, Washington • Graduate, Missouri State Highway Patrol Law Enforcement Academy • Graduate, Missouri State Highway Patrol undercover narcotics investigator training program. • Graduate, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) undercover narcotics investigator training program. • Graduate, Mid States Organized Crime Information Center (MOCIC) narcotic investigators Criminal Intelligence Techniques training program. • Graduate, Springfield, Missouri Police Department Academy • Graduate, 186th FBI National Academy LAW ENFORCEMENT/PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Poplar Bluff, Missouri Police Department • April 1979 through February 1981-Patrol Officer • February 1981 through August 1982-Narcotics Detective Springfield, Missouri Police Department • August 1982-1000 hour Springfield Police academy training • January 1983-uniformed patrol officer • September 1985-undercover narcotics investigator and Federal Drug Task Force member-Commissioned Deputy Untied States Marshal • October 1987-uniformed patrol • July 1988-Detective-criminal investigations and undercover narcotics investigations • September 1989-Sergeant-criminal investigations • April 1990-Crisis Action Team leader/sergeant (SWAT) • December 1992-Lieutenant, Special Operations Commander-overseeing all SWAT and narcotics -

Evolution of Police Monitoring in Peace Operations

12 Evolution of police monitoring in peace operations J. Matthew Vaccaro ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ C are often conducted in failed states or in those emerging from civil conflict. In these environments, the local criminal justice system has often been largely destroyed or has become otherwise ineffective as a result of widespread corruption among its constituent parts and/or their involve- ment in the war. This problem is exemplified by the state of indigenous police forces at the beginning of recent peace operations. In Somalia, for instance, the police were inoperative: they left their posts when a central government failed to emerge after President Siad Barre was deposed in 1991. In Haiti, the police were integrated into the armed forces and used by the ruling junta to repress the popula- tion. When the multinational peacekeeping force arrived in September 1994 and broke the regime’s stranglehold, police officers stopped doing their jobs and assumed a defensive posture, fearing that ordinary citizens would seek retribution. In Bosnia- Herzegovina, where police forces had been segregated along ethnic lines and had participated in the sectarian conflict, the police attempted to continue the fighting through intimidation and thuggery throughout the tenure of the United Nations Protection Force () (1992–95). In the ethnically polarised Kosovo conflict, the police were a primary player in the ‘ethnic cleansing’ and were forced to leave the province as part of the settlement granting access to North Atlantic Treaty Organization () troops and the establishment of a United Nations () administration. Furthermore, in each of these situations the other components of the criminal justice system—the courts, prisons and, in a less tangible way, the laws of state—were also absent, ineffective or unjust. -

Haiti Earthquake: Crisis and Response

Haiti Earthquake: Crisis and Response Rhoda Margesson Specialist in International Humanitarian Policy Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs February 2, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41023 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Haiti Earthquake: Crisis and Response Summary The largest earthquake ever recorded in Haiti devastated parts of the country, including the capital, on January 12, 2010. The quake, centered about 15 miles southwest of Port-au-Prince, had a magnitude of 7.0. A series of strong aftershocks have followed. The damage is severe and catastrophic. It is estimated that 3 million people, approximately one third of the overall population, have been affected by the earthquake. The Government of Haiti is reporting an estimated 112,000 deaths and 194,000 injured. In the immediate wake of the earthquake, President Preval described conditions in his country as “unimaginable,” and appealed for international assistance. As immediate needs are met and the humanitarian relief operation continues, the government is struggling to restore the institutions needed for it to function, ensure political stability, and address long-term reconstruction and development planning. Prior to the earthquake, the international community was providing extensive development and humanitarian assistance to Haiti. With that assistance, the Haitian government had made significant progress in recent years in many areas of its development strategy. The destruction of Haiti’s nascent infrastructure and other extensive damage caused by the earthquake will set back Haiti’s development significantly. Haiti’s long-term development plans will need to be revised. The sheer scale of the relief effort in Haiti has brought together tremendous capacity and willingness to help. -

Examining the Urban Dimension of the Security Sector

Examining the Urban Dimension of the Security Sector Research Report Project Title: Providing Security in Urban Environments: The Role of Security Sector Governance and Reform Project supported by the Folke Bernadotte Academy (FBA) and the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) February 2018 Authors (in alphabetical order): Andrea Florence de Mello Aguiar, Lea Ellmanns, Ulrike Franke, Praveen Gunaseelan, Gustav Meibauer, Carmen Müller, Albrecht Schnabel, Usha Trepp, Raphaël Zaffran, Raphael Zumsteg 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents Authors Acknowledgements List of Abbreviations 1 Introduction: The New Urban Security Disorder 1.1 Puzzle and research problem 1.2 Purpose and research objectives 1.3 Research questions 1.4 Research hypotheses 1.5 Methodology 1.6 Outline of the project report 2 Studying the Security Sector in Urban Environments 2.1 Defining the urban context 2.2 Urbanisation trends 2.3 Urban security challenges 2.4 Security provision in urban contexts 2.5 The ‘generic’ urban security sector 2.6 Defining SSG and SSR: from national to urban contexts 3 The Urban SSG/R Context: Urban Threats and Urban Security Institutions 3.1 The urban SSG/R context: a microcosm of national SSG/R contexts 3.2 The urban environment: priority research themes and identified gaps 3.3 Excursus: The emergence of a European crime prevention policy 3.4 Threats prevalent and/or unique to the urban context – and institutions involved in threat mitigation 3.5 The urban security sector: key security, management and oversight institutions -

Congressional Record—Senate S2006

S2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 6, 1997 to all of those who are suffering and all market principles. In Latin America, This is one area in which American those who are fighting back, trying to the Reagan doctrine certainly has expertise can make a big difference. In- put their lives back in order. worked. deed, with some extra United States I see on the floor my colleague from As free elections and economic liber- help, Haiti could succeed in convicting Ohio and my colleague from Kentucky alization has taken place in country some of the worst defenders, like the and my colleague from West Virginia. after country, the countries of South murderers of Mireille Bertin and Guy All are States, as well as Indiana, that and Central America have become bet- Malary. Mireille Bertin was an anti- have been hit very hard. ter neighbors for the United States. I Aristide lawyer. Guy Malary was The most heartening thing to see believe these same principles apply to Aristide’s justice minister. To pros- during a tragedy such as this is how our national strategy in regard to ecute and convict the killers in those people react. We have many organiza- Haiti. kinds of cases would send an unmistak- tions that are involved, but probably Mr. President, we need to apply these able message to Haitian society: Your the biggest organization involved is principles to Haiti so that over the chance of getting justice does not de- not an organization at all, it is just long term, Haiti can move out of the pend on what side you are on. -

Report on Haiti, 'Failed Justice Or Rule of Law?'

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser/L/V/II.123 doc.6 rev 1 26 October 2005 Original: English HAITI: FAILED JUSTICE OR THE RULE OF LAW? CHALLENGES AHEAD FOR HAITI AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY GENERAL SECRETARIAT ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES WASHINGTON D.C. 2006 2006 http://www.cidh.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Haiti: Failed Justice or the Rule of Law? Challenges Ahead for Haiti and the International Community 2005 / Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. p. ; cm. (OAS Official Records Series. OEA Ser.L/V/II.123) ISBN 0-8270-4927-7 1. Justice, Administration of--Haiti. 2. Human rights--Haiti. 3. Civil rights--Haiti. I. Title. II Series. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.123 (E) HAITI: FAILED JUSTICE OR THE RULE OF LAW? CHALLENGES AHEAD FOR HAITI AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. v I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................5 II. BACKGROUND ..............................................................................6 A. Events in Haiti, 2003-2005 ..................................................6 B. Sources of Information in Preparing the Report ..................... 11 C. Processing and Approval of the Report................................. 14 III. ANALYSIS OF THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN HAITI ............ 17 A. Context for Analysis .......................................................... 17 -

Keeping the Peace in Haiti?

KEEPING THE PEACE IN HAITI? An Assessment of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti Using Compliance with its Prescribed Mandate as a Barometer for Success March 2005 Harvard Law Student Advocates for Human Rights, Cambridge, Massachusetts & Centro de Justiça Global, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, Brazil March 2005 Keeping the Peace in Haiti? TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ____________________________________________________________ 1 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 2 I. RECOMMENDATIONS ____________________________________________________________ 2 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF HAITI _____________________________________________________ 4 III. RESOLUTION 1542: THE MINUSTAH MANDATE __________________________________ 12 III.A. Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration_____________________________ 12 III.B. Institutional Strengthening: Police Reform and the Constitutional and Political Process _______________________________________________________________ 13 III.B.1. Police Reform________________________________________________________ 13 III.B.2. The Constitutional and Political Process __________________________________ 14 III.C. Human Rights and Civilian Protection _____________________________________ 15 III.C.1. Human Rights________________________________________________________ 15 III.C.2. Civilian Protection____________________________________________________ 19 IV. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ______________________________________________________ 21 IV.A. Methodology ___________________________________________________________ -

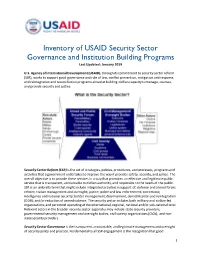

Inventory of USAID Security Sector Governance and Institution Building Programs Last Updated: January 2019

Inventory of USAID Security Sector Governance and Institution Building Programs Last Updated: January 2019 U.S. Agency of International Development (USAID), throughitscommitment to security sector reform (SSR), works to support good governance and rule of law, conflict prevention, mitigation and response, and reintegrationand reconciliation programs aimed at building civilian capacity tomanage, oversee, and provide security and justice. Security Sector Reform (SSR) is the set of strategies, policies, procedures, and processes, programs and activities that a government undertakes to improve the way it provides safety, security, and justice. The overall objective is to provide these services in a way that promotes an effective and legitimate public service that is transparent, accountable to civilian authority, and responsive to the needs of the public. SSR is an umbrella term that might include integratedactivitiesin support of: defense and armed forces reform; civilian management and oversight; justice; police and law enforcement; corrections; intelligence and national security; border management; disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR); and/or reduction of armed violence. The security sector includes both military and civilian-led organizations, and personnel operating at the international, regional, national and/or sub-national level. Relevant actors in the broader security sector apparatusmay include state security providers, governmentalsecurity management and oversight bodies, civil society organizations(CSOs), and non- state security providers. Security Sector Governance is the transparent, accountable, and legitimate management and oversight of security policy and practice. Fundamental to all SSR engagement is the recognition that good 1 governance- the effective, equitable, responsive, transparent, and accountable management of public affairs and resources – and the rule of law are essential to an effective security sector. -

Reforming Haiti's Security Sector

REFORMING HAITI’S SECURITY SECTOR Latin America/Caribbean Report N°28 – 18 September 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. SECURITY IN HAITI TODAY....................................................................................... 2 III. POLICE REFORM........................................................................................................... 7 A. VETTING AND TRAINING ..............................................................................................................9 B. BORDER INITIATIVES .................................................................................................................11 C. REESTABLISHING THE ARMY?....................................................................................................13 D. COMMUNITY VIOLENCE REDUCTION .........................................................................................14 IV. JUSTICE REFORM ....................................................................................................... 16 A. INDEPENDENCE AND STRENGTHENING OF THE JUDICIARY..........................................................16 B. PRISON REFORM ........................................................................................................................17 1. Conditions of imprisonment ......................................................................................................17 -

National Police Reform Plan

United Nations S/2006/726 Security Council Distr.: General 12 September 2006 Original: English Letter dated 31 August 2006 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council Further to Security Council resolution 1608 (2005), I have the honour to convey a letter dated 18 August 2006 from Jean Rénald Clérismé, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Haiti (see annex), confirming the adoption of a plan for the reform of the Haitian National Police and enclosing a copy of the plan. I should be grateful if you would bring this letter and its annex to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) Kofi A. Annan 06-51735 (E) 061006 061006 *0651735* S/2006/726 Annex Letter dated 18 August 2006 from the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Haiti to the Secretary-General [Original: French] I have the honour to share with the members of the Security Council, pursuant to Security Council resolution 1608 (2005), the reform plan of the Haitian National Police, elaborated in coordination with MINUSTAH, and adopted by the Government of Haiti on 8 August 2006. This plan, which now constitutes a component of security sector policy represents the joint efforts of the Government of Haiti and MINUSTAH to make progress in the area of reform. The Government of Haiti undertakes to implement this reform plan for the Haitian National Police in close cooperation with MINUSTAH and the international community, but notes that its success depends on the latter’s ongoing support. I should be grateful if the contents of this letter and its enclosure could be brought to the attention of the Security Council. -

Haiti's Human Rights Record

The Human Rights Record of the Haitian National Police Human Rights Watch/Americas, National Coalition for Haitian Rights, Washington Office on Latin America I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS The Haitian National Police (Police Nationale d’Haïti, HNP) constitutes the first civilian, professional police force in Haiti’s 193-year history. In past decades, Haiti's military controlled a subservient police, and both institutions engaged in widespread, systematic human rights abuses. Following former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide's dismantling of the military in 1995, Haiti's transition to a civilian-controlled police has been marred by serious human rights violations. In the year and a half since its deployment, members of this U.S.-trained force have committed serious abuses, including torture and summary executions. Political authorities condemned many of the abuses and senior police authorities sanctioned or fired some of the responsible personnel, but the HNP only recently began to refer cases of police abuses to the courts. While a number of HNP agents now face criminal prosecution, Haiti's dysfunctional judicial system has made meager progress on prosecuting police abuse cases. Not one policeman or woman has been convicted of any killing. Since the HNP commenced operations in July 1995, agents and officers have killed at least forty- six Haitians. A minority of these deaths occurred when police agents used deadly force in legitimate self-defense. Most of the dead suffered extrajudicial executions or the excessive, unjustified use of lethal force by the police. The worst incident of police abuse occurred on March 6, 1996, in the Port-au-Prince shantytown of Cité Soleil, when the HNP summarily killed at least six men.