Platform Regulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Political Science Review Vol. XXI, No. 1 2021

Romanian Political Science Review vol. XXI, no. 1 2021 The end of the Cold War, and the extinction of communism both as an ideology and a practice of government, not only have made possible an unparalleled experiment in building a democratic order in Central and Eastern Europe, but have opened up a most extraordinary intellectual opportunity: to understand, compare and eventually appraise what had previously been neither understandable nor comparable. Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review was established in the realization that the problems and concerns of both new and old democracies are beginning to converge. The journal fosters the work of the first generations of Romanian political scientists permeated by a sense of critical engagement with European and American intellectual and political traditions that inspired and explained the modern notions of democracy, pluralism, political liberty, individual freedom, and civil rights. Believing that ideas do matter, the Editors share a common commitment as intellectuals and scholars to try to shed light on the major political problems facing Romania, a country that has recently undergone unprecedented political and social changes. They think of Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review as a challenge and a mandate to be involved in scholarly issues of fundamental importance, related not only to the democratization of Romanian polity and politics, to the “great transformation” that is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe, but also to the make-over of the assumptions and prospects of their discipline. They hope to be joined in by those scholars in other countries who feel that the demise of communism calls for a new political science able to reassess the very foundations of democratic ideals and procedures. -

Robert Helbig NATO-Brazil Relations

Helbig 1 Robert Helbig NATO-Brazil relations: Limits of a partnership policy Professor Michelle Egan, School of International Service University Honors in International Studies Fall 2012 Helbig 2 Abstract The purpose of this capstone project is to assess the potential of a partnership between NATO and Brazil, based on interviews with over twenty high-level experts on Brazilian foreign policy and the application of international relations theory. Because building international partnership has become a vital task of NATO and Brazil is trying to increase its influence in global politics, senior NATO officials have called for the Alliance to reach out to Brazil. The paper argues that Brazil, as a regional middle power, has taken on a soft-balancing approach towards the US, thereby following adversary strategies to NATO, including global governance reform and South- South cooperation. The theoretical debate on alliance formation and international regimes leads to the conclusion that NATO is unlikely to succeed in reaching out to Brazil, which is why NATO should develop different approaches of increasing its influence in South America and the South Atlantic. Helbig 3 Outline I. Introduction II. Brazil as an actor in international relations II.I. Brazil’s mindset III.II. Global aspirations vs. regional supremacy II.III. Bilateralism, multilateralism and global governance geform II.IV. Brazil’s role on the global stage II.V. Brazil’s stance on the United States – From Rio Branco to soft-balancing II.VI. Brazil’s stance on nuclear proliferation – an example of opposing the established world order II.VII. Brazilian security – the green and the blue Amazon II.IIX. -

Stakes Are High: Essays on Brazil and the Future of the Global Internet

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Global Communication Studies Internet Policy Observatory (CGCS) 4-2014 Stakes are High: Essays on Brazil and the Future of the Global Internet Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Ronaldo Lemos Wolfgang Schulz Markus Beckedahl Juliana Nolasco Ferreira See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/internetpolicyobservatory Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Price, Monroe; Lemos, Ronaldo; Schulz, Wolfgang; Beckedahl, Markus; Nolasco Ferreira, Juliana; Hill, Richard; and Biddle, Ellery. (2014). Stakes are High: Essays on Brazil and the Future of the Global Internet. Internet Policy Observatory. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/internetpolicyobservatory/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/internetpolicyobservatory/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stakes are High: Essays on Brazil and the Future of the Global Internet Abstract This workbook seeks to provide some background to the Global Meeting on the Future of Internet Governance (NETmundial) scheduled for April 23rd and 24th 2014 in São Paulo, Brazil. It is designed to help outline the internet policy issues that are at stake and will be discussed at NETmundial, as well as background on internet policy in Brazil. The workbook includes essays on the history of the NETmundial meeting and the Marco Civil process in Brazil; some background on the environment in Germany—with particular attention to the link between the meeting and the Snowden case; questions of legitimacy surrounding open processes for lawmaking; and comments on the material presented to the organizing committee by official and unofficial commenters. -

No Monitoring Obligations’ the Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ a Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F

The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ A Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F. Frosio* Abstract: In imposing a strict liability regime pean Commission, would like to introduce filtering for alleged copyright infringement occurring on You- obligations for intermediaries in both copyright and Tube, Justice Salomão of the Brazilian Superior Tribu- AVMS legislations. Meanwhile, online platforms have nal de Justiça stated that “if Google created an ‘un- already set up miscellaneous filtering schemes on a tameable monster,’ it should be the only one charged voluntary basis. In this paper, I suggest that we are with any disastrous consequences generated by the witnessing the death of “no monitoring obligations,” lack of control of the users of its websites.” In order a well-marked trend in intermediary liability policy to tame the monster, the Brazilian Superior Court that can be contextualized within the emergence of had to impose monitoring obligations on Youtube; a broader move towards private enforcement online this was not an isolated case. Proactive monitoring and intermediaries’ self-intervention. In addition, fil- and filtering found their way into the legal system as tering and monitoring will be dealt almost exclusively a privileged enforcement strategy through legisla- through automatic infringement assessment sys- tion, judicial decisions, and private ordering. In multi- tems. Due process and fundamental guarantees get ple jurisdictions, recent case law has imposed proac- mauled by algorithmic enforcement, which might fi- tive monitoring obligations on intermediaries across nally slay “no monitoring obligations” and fundamen- the entire spectrum of intermediary liability subject tal rights online, together with the untameable mon- matters. -

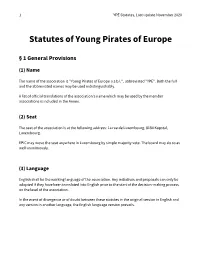

YPE Statutes, Last Update November 2020

1 YPE Statutes, Last update November 2020 Statutes of Young Pirates of Europe § 1 General Provisions (1) Name The name of the association is "Young Pirates of Europe a.s.b.l.", abbreviated "YPE". Both the full and the abbreviated names may be used indistinguishably. A list of official translations of the association's name which may be used by the member associations is included in the Annex. (2) Seat The seat of the association is at the following address: 1a rue de Luxembourg, 8184 Kopstal, Luxembourg. EPIC may move the seat anywhere in Luxembourg by simple majority vote. The board may do so as well unanimously. (3) Language English shall be the working language of the association. Any initiatives and proposals can only be adopted if they have been translated into English prior to the start of the decision-making process on the level of the association. In the event of divergence or of doubt between these statutes in the original version in English and any version in another language, the English language version prevails. 2 YPE Statutes, Last update November 2020 § 2 Goals The main goal of YPE is to bring together European pirate youth organisations and other youth organisations that work on digital issues and for transparency in government, participating democracy and civil rights as well as their members, improving not only the coordination of their political work, but also supporting cultural and personal exchange. As a federation of youth organisations, education and personal development of young people as well as the exchange of ideas and support of eachother is an equally important aim of YPE. -

The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age

The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age April 9, 2018 Dr. Keith Goldstein, Dr. Ohad Shem Tov, and Mr. Dan Prazeres Presented on behalf of Pirate Parties International Headquarters, a UN ECOSOC Consultative Member, for the Report of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Our Dystopian Present Living in modern society, we are profiled. We accept the necessity to hand over intimate details about ourselves to proper authorities and presume they will keep this information secure- only to be used under the most egregious cases with legal justifications. Parents provide governments with information about their children to obtain necessary services, such as health care. We reciprocate the forfeiture of our intimate details by accepting the fine print on every form we sign- or button we press. In doing so, we enable second-hand trading of our personal information, exponentially increasing the likelihood that our data will be utilized for illegitimate purposes. Often without our awareness or consent, detection devices track our movements, our preferences, and any information they are capable of mining from our digital existence. This data is used to manipulate us, rob from us, and engage in prejudice against us- at times legally. We are stalked by algorithms that profile all of us. This is not a dystopian outlook on the future or paranoia. This is present day reality, whereby we live in a data-driven society with ubiquitous corruption that enables a small number of individuals to transgress a destitute mass of phone and internet media users. In this paper we present a few examples from around the world of both violations of privacy and accomplishments to protect privacy in online environments. -

Those Who Claim That Significant Copyright-Related Benefits Flow from Greater International Uniformity of Terms Point to T

Issue 5 - October 2015 Dear Colleagues, It is with great pleasure that we are presenting the fifth issue of this Newsletter, the purpose of which is to provide a platform for the exchange of experiences and ideas among staffers of the European Parliament and the Congress in the area of legal affairs. The main purpose of this issue is to introduce the Members of the Legal Affairs Committee of the European Parliament (JURI) who will be visiting Washington, DC on November 3-6, 2015, as announced in the the last newsletter from July 2015. An ambitious programme of meetings has been set up with the purpose of discussing questions relating primarily to Civil Justice, Private International Law and Intellectual Property Rights, with both public counterparts and private stakeholders. This newsletter will also include brief background descriptions in view of the meetings that the Committee delegation will hold in Congress, with the US Administration and the Supreme Court, as well as with civil society and industry. The week of the visit will be a busy one indeed for the European Parliament in the US capital, with close to 40 MEPs visiting at the same time. In addition to the Members from JURI, the Constitutional Affairs Committee (AFCO) and Parliament's Standing Delegation for relations with the US will also have Members visiting with official missions, the latter for an interparliamentary meeting (IPM) in the context of the Transatlantic Legislative Dialogue (TLD). Political groups from Parliament and individual Members are also visiting Washington next week with their own agendas and meeting programmes. -

Forum Mondial De La Démocratie Strasbourg 2013

CONNECTER CONNECTING LES INSTITUTIONS INSTITUTIONS AVEC LES CITOYENS AND CITIZENS À L’ÈRE DU NUMÉRIQUE IN THE DIGITAL AGE 2 3 F ORUM MONDIAL DE LA SR T ASBOURG WORLD FORUM DÉMOCRATIE STRASBOURG 2013 FOR DEMOCRACY 2013 ■ Réseaux sociaux, blogs, médias en ligne semblent offrir aux citoyens un ■ Social networks, blogs, and online media offer citizens an access to public accès à la vie publique qui n’aura jamais été aussi direct. Internet est-il en train life which has never before been so direct. Is the internet revolutionising our de révolutionner nos usages démocratiques ? C’est cette question d’actualité democratic practices? This is the topical issue which will be raised this year que pose, cette année, le Forum mondial de la démocratie, organisé par le by the World Forum for Democracy, organized by the Council of Europe, Conseil de l’Europe, avec le soutien du gouvernement français, de la Région with the support of the French government, the Région Alsace and the City Alsace et de la Ville de Strasbourg. Internet est devenu, ces dernières années, of Strasbourg. Over the past few years the internet has become an area of un espace d’innovation démocratique débordant de vitalité. Chaque jour, des democratic innovation which is overflowing with vitality. Every day, partici- sites participatifs sont créés à l’initiative des Parlements, des gouvernements pative websites are created by parliaments, governments or local authorities, ou des collectivités locales ; ils permettent aux citoyens de contribuer direc- allowing citizens to contribute directly to the decision-making process, to tement à la prise de décisions, de débattre en temps réel d’options politiques debate specific political options in real-time and to influence the decisions particulières et d’influer sur les décisions des élus. -

Piraattipuolueen Ja Piraattinuorten Tiedotuslehti

Piraattipuolueen ja piraattinuorten tiedotuslehti 1/2014 Purje 1 Puheenjohtaja Sisällys Valvonta- ja urkintaskandaalit tuovat yhä uudes- taan esiin globaalin tietoyhteiskunnan uhat. Järjes- telmässä on haavoittuvuuksia, joita käytetään kaiken aikaa hyväksi. On hyvä, että erilaiset paljastukset valtioiden harjoit- tamasta urkinnasta nostavat voimakkaan vastustus- reaktion kansalaisissa, mutta julkinen keskustelu lähtee yleensä heti alussa väärille raiteille. Puhu- taan diplomaattisista suhteista ja maailman valta- politiikasta: keskustelua käydään puhtaasti 1900- luvun konseptein. Olennaista olisi keskustella tietoverkkojen raken- teesta, koodista, rajapinnoista: tämä on keskustelu jota tällä hetkellä käydään vain hyvin rajallisesti asiantuntijapiireissä. Tällöin jää ymmärtämättä, Harri Kivistö on Piraattipuolueen puheenjohtaja ja puolueenperus- ajajäsen. Harri opiskelee tampereen yliopistossa englantilaista filolo- että kysymykset tiedon vapaudesta, sähköisistä giaa ja viimeistelee nyt kirjallisuustieteen gradua. kansalaisoikeuksista ja yksityisyydestä ovat täysin poliittisia kysymyksiä. Ne sisältävät aivan keskeisiä arvovalintoja. Jos näitä valintoja ei tehdä politii- kassa avoimesti, ne tehdään kabineteissa valtaeliitin tai liikemaailman etujen mukaan. Tämän vuoksi Piraattipuoluetta tarvitaan nyt Tästä syystä meidän ei tule pelätä esimerkiksi enemmän kuin koskaan. Sen lisäksi, että meillä sellaista tulevaisuudennäkymää, jossa valtiovallat on arvokasta teknistä ymmärrystä tietoverkkojen menettävät merkitystään, vaikka ne tällä hetkellä -

European Youth Foundation

EUROPEAN YOUTH FOUNDATION 2017 Annual report EUROPEAN YOUTH FOUNDATION 2017 Annual report Prepared by the secretariat of the European Youth Foundation, Youth Department Directorate of Democratic Citizenship and Participation DG Democracy Council of Europe French edition: Le Fonds Européen pour la Jeunesse Rapport annuel 2017 All requests concerning the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Directorate of Communication (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). Cover and layout: All other correspondence concerning this Documents and publications document should be addressed to: production Department (SPDP), Council of Europe European Youth Foundation 30, rue Pierre de Coubertin Photos: Council of Europe, ©shutterstock F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex France © Council of Europe, February 2018 E-mail: [email protected] Printed at the Council of Europe CONTENTS THE EUROPEAN YOUTH FOUNDATION 5 Key figures 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PARTNER NGOs 9 EYF SUPPORT 10 1. Annual work plans 11 2. International activities 11 3. Pilot activities 11 4. Structural grants 12 5. Integrated grant 12 EYF PRIORITIES 13 1. Young people and decision-making 13 2. Young people’s access to rights 15 3. Intercultural dialogue and peacebuilding 16 4. Priorities for pilot activities 17 FLAGSHIP ACTIVITIES OF THE EYF 19 1. Visits to EYF-supported projects 19 2. EYF seminars 19 3. EYF information sessions 20 4. Other EYF presentations 20 SPECIFICITY OF THE EYF 21 1. Volunteer Time Recognition 21 2. Gender perspectives 21 3. Non-formal education -

Pirátské Strany V Evropě

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra mezinárodních vztahů a evropských studií Pirátské strany v Evropě Magisterská diplomová práce Eva Křivánková (učo 237862) Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Petr Kaniok, Ph.D. Obor: Evropská studia Imatrikulační ročník: 2011 Brno, 2014 1 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem tento text vypracovala samostatně pouze s vyuţitím uvedených zdrojů. 19. 5. 2014 ………………………………. Eva Křivánková 2 Děkuji vedoucímu této práce PhDr. Petru Kaniokovi, Ph.D. za jeho čas a cenné rady. 3 Obsah Úvod ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 1 Teoretické ukotvení ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Cíle a struktura ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.2 Stranické rodiny a jejich určení ............................................................................................... 8 1.3 Úskalí konceptu stranických rodin .......................................................................................... 9 1.3.1 Stručný přehled stranických rodin ................................................................................. 10 1.4 Koncept stranických rodin a pirátské hnutí ........................................................................... 12 1.5 Metody ................................................................................................................................. -

Candidate List - Abbreviated ALL COUNTIES 2018 GENERAL ELECTION - 11/6/2018 11:59:00 PM

Candidate List - Abbreviated ALL COUNTIES 2018 GENERAL ELECTION - 11/6/2018 11:59:00 PM OFFICE CATEGORY: US SENATOR BALLOT NAME PARTY OFFICE TITLE FILED DATE Joe Donnelly Democratic United States Senator from Indiana 2/1/2018 Lucy M. Brenton Libertarian United States Senator from Indiana 5/10/2018 Mike Braun Republican United States Senator from Indiana 1/31/2018 Nathan Altman Write-In (Independent) United States Senator from Indiana 6/27/2018 Christopher Fischer Write-In (Independent) United States Senator from Indiana 7/2/2018 James L. Johnson Jr. Write-In (Other) United States Senator from Indiana 1/11/2018 OFFICE CATEGORY: SECRETARY OF STATE BALLOT NAME PARTY OFFICE TITLE FILED DATE Jim Harper Democratic Secretary of State 6/18/2018 Mark W. Rutherford Libertarian Secretary of State 5/14/2018 Connie Lawson Republican Secretary of State 6/13/2018 George William Wolfe Write-In (Green) Secretary of State 6/26/2018 Jeremy Heath Write-In (Pirate Party) Secretary of State 6/27/2018 OFFICE CATEGORY: AUDITOR OF STATE BALLOT NAME PARTY OFFICE TITLE FILED DATE Joselyn Whitticker Democratic Auditor of State 6/26/2018 John Schick Libertarian Auditor of State 5/10/2018 Tera Klutz Republican Auditor of State 6/13/2018 OFFICE CATEGORY: TREASURER OF STATE BALLOT NAME PARTY OFFICE TITLE FILED DATE John C. Aguilera Democratic Treasurer of State 6/25/2018 Kelly Mitchell Republican Treasurer of State 6/13/2018 OFFICE CATEGORY: US REPRESENTATIVE BALLOT NAME PARTY OFFICE TITLE FILED DATE Peter J. Visclosky Democratic United States Representative, First District 1/10/2018 Mark Leyva Republican United States Representative, First District 1/22/2018 Jonathan S.