Speculations on History's Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Directory 2011

Travel Directory 2011 ITOC - Celebrating 40 years THE DISTRIBUTION CHANNEL for NEw Zealand Tourism mARKETING NEw ZEALAND OVERSEAS 1971-2011 Open daily from 10am • Cnr Great South & Wiri Station Roads, Manukau Infoline: 09 262 2044 • www.rainbowsend.co.nz www.itoc.org.nz Welcome Published in association with the Inbound Tour Operators Council PO Box 1888, Wellington 6140 Welcome to the New Zealand Inbound Travel Directory 2011, New Zealand your authoritative guide to those New Zealand tour operators Phone +64 4 496 4898 and suppliers who handle a large share of New Zealand's Fax +64 4 499 0786 Email [email protected] inbound tourism business and who are members of the Website www.itoc.org.nz Inbound Tour Operators Council (ITOC). We know from feedback that this annual publication is valued as a major source of information by our New Zealand Publisher members and overseas tour wholesalers and retail TPL Media PO Box 9596, Newmarket travel agencies. Auckland 1149, New Zealand Phone +64 9 529 3000 ITOC plays an important role within the country's tourism Fax +64 9 529 3001 Email [email protected] industry and enjoys a close working relationship with the various Regional Tourism Organisations, Tourism New Editor Zealand, Qualmark and other key national tourism bodies. Gordon Gillan Phone +64 9 529 3026 Our focus is very much on stimulating business to business relationships between companies throughout the travel Sales Manager distribution chain as well as in enhancing quality and Pam Brown Phone: +64 9 529 3003 adding value. Production Manager In recent years ITOC has strengthened its focus on quality by Lisa Morris implementing an Inbound Tour Operator accreditation system Advertising Co-ordinator in conjunction with Qualmark. -

Our Natural Capital

Our Natural Capital Wellington’s biodiversity strategy and action plan 2015 Cover photo: Juvenile New Zealand fur seal at Frank Kitts Park, Wellington City. The main Wellington seal colony is at Sinclair Head on the edge of Te Kopahau Reserve. This is a “haul out” area for New Zealand fur seals during winter (May–October). Breeding season is November–January. New Zealand fur seals are also seen around Wellington Harbour. When around seals, people are advised to stay at least 10 metres away and to keep their dogs on a lead. New Zealand fur seals – particularly those living near the city – connect people with the natural world and represent the link between the marine and terrestrial environments. Our Natural Capital 3 Contents 1. Summary 4 10. Measuring Wellington City Council’s performance 61 Part One: Strategy 7 10.1 City Biodiversity Index 61 2. Introduction 7 10.2 Operational monitoring 65 2.2 What is natural capital? 7 11. Rationale for goals, objectives and actions 67 2.3 What is biodiversity? 8 11.1 Protect 67 2.4 Why is this important? 9 11.2 Restore 77 3. Māori and mana whenua relationship 11.3 Connect 84 to biodiversity 13 11.4 Research 91 4. Vision 15 Glossary 97 5. Guiding principles 17 Appendix 1 – Policy context 100 6. Policy framework 19 Appendix 2 – Ecological significance criteria 104 7. Wellington’s biodiversity journey 21 Appendix 3 – Wellington’s vegetation 106 7.1 Past 21 Appendix 4 – Significant Ecological Sites 107 7.2 Present 22 7.3 Future 30 Appendix 5 – Nationally threatened, regionally threatened and locally significant species 108 8. -

A Guide to Wellington Architecture

1908 Tramways Building 1928 Evening Post Building 1942 Former State Insurance 1979 Freyburg Building 1987 Leadenhall House 1999 Summit Apartments 1 Thorndon Quay 82 Willis St Office Building 2 Aitken St 234 Wakefield St 182 Molesworth St 143 Lambton Quay Futuna Chapel John Campbell 100 William Fielding 36 MOW under Peter Sheppard Craig Craig Moller 188 Jasmax 86 5 Gummer & Ford 60 Hoogerbrug & Scott Architects by completion date by completion date 92 6 St Mary’s Church 1909 Harbour Board Shed 21 1928 Former Public Toilets 1987 Museum Hotel 2000 VUW Adam Art Gallery Frederick de Jersey Clere 1911 St Mary’s Church 2002 Karori Swimming Pool 1863 Spinks Cottage 28 Waterloo Quay (converted to restaurant) 1947 City Council Building 1979 Willis St Village 90 Cable St Kelburn Campus 170 Karori Rd 22 Donald St 176 Willis St James Marchbanks 110 Kent & Cambridge Terraces 101 Wakefield St 142-148 Willis St Geoff Richards 187 Athfield Architects 8 Karori Shopping Centre Frederick de Jersey Clere 6 Hunt Davis Tennent 7 William Spinks 27 City Engineer’s Department 199 Fearn Page & Haughton 177 Roger Walker 30 King & Dawson 4 1909 Public Trust Building 1987 VUW Murphy Building 2000 Westpac Trust Stadium 1960 Futuna Chapel 2005 Karori Library 1866 Old St Paul's Church 131-135 Lambton Quay 1928 Kirkcaldie & Stains 1947 Dixon St Flats 1980 Court of Appeal & Overbridge 147 Waterloo Quay 62 Friend St 247 Karori Rd 34-42 Mulgrave St John Campbell 116 Refurbishments 134 Dixon St cnr Molesworth & Aitken Sts Kelburn Campus Warren & Mahoney Hoogerbrug Warren -

Green Space in Wellington's Central City

Green Space in Wellington’s Central City: Current provision, and design for future wellbeing Report for Wellington City Council October 2019 Authors: Paul Blaschke, Ralph Chapman, Elaine Gyde, Philippa Howden-Chapman, Jenny Ombler, Maibritt Pedersen Zari, Meredith Perry, Ed Randal. Key points summary • Green space is needed in central city areas to provide health and wellbeing benefits for current and future residents, commuters and visitors, and increased amenity, liveability and economic benefits. Green spaces also provide ecosystem and resilience benefits that will help mitigate and adapt the city to climate change and other environmental shocks. • We report here on a detailed study of the provision of public green space in central Wellington City in relation to current and projected future population levels. • The study focused on the three Census Area Units (CAU) of central Wellington City. These CAUs contain a total of 41.19 ha of public green space. More than half of the central city’s public green space is located not in City parks and gardens but in road reserves or in other non-council areas, and some is of relatively low quality and poorly accessible. • The amount of green space per capita in each CAU is highest at 41m2 in Thorndon-Tinakori Road CAU, 23m2 in Lambton CAU, and lowest at 6m2 in Willis St-Cambridge Terrace CAU. There is a very significant lack of greenspace within 300m of the population-weighted centre of the Willis St– Cambridge Terrace CAU. • Green space amount per capita in central Wellington City declines substantially - by half on average - when projected population growth to 2043 for the three CAUs is considered. -

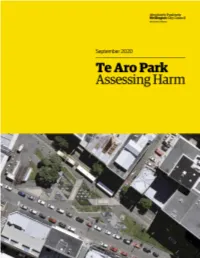

Te Aro Park, Actions Taken to Date and Potential Solutions

Executive Summary This report outlines safety concerns within Te Aro Park, actions taken to date and potential solutions. The numbers of events associated with social harm, occurring within the park are consistently higher in Te Aro Park than other central city parks. In order to improve safety within Te Aro Park the report outlines a number of options to address these issues, which have been categorised into projects for possible implementation over short, medium and long term and are outlined below. Short Term - as at January 2020 • Increased maintenance of the park – inclusion of Te Aro Park in the Central City Cleaning contract. • Removal of the canopy between the two toilet blocks and addition of directional lighting. • Lighting changes o If the canopy between the two toilets is not removed, additional lighting should be installed. o Vertical lighting should be installed on the Opera House side to improve night-time flow and a more defined route. o Lighting should also be added to the murals on the toilet building to increase attention to the artwork. o Lights should be added to the canopy of the Oaks building o Canopy lighting should be added to the tree. • Remove Spark phone booth as it creates blind spots and concealments. • Installing pedestrian crossings into both Manners and Dixon street to improve safe access to the park • Increase patrols to the Te Aro Park area during the hours of high activity and high social harm - this includes Police, Local Hosts and Maori Wardens • Improve guardianship of the park by involving businesses and other stakeholders in activity that occurs within the park, with central coordination from Council and intentional place-making Medium Term • Recognise and acknowledge the cultural significance of the park with interpretive signage and revitalise the park into more of a destination. -

Schedule One: Restricted and Prohibited Areas for Freedom Camping

SCHEDULE ONE: RESTRICTED AND PROHIBITED AREAS FOR CAMPING Camping in Wellington is restricted or prohibited as illustrated and described within the following aerial photographs. Glover Park Te Aro Park Midland Park Central Railway Station Post Office Square Waitangi Park Frank Kitts Park Prohibited Camping Areas 0 80 160 320 metres , Wellington C.B.D. I E'.'ZJ Proh ibited scale 1:s. ooo Property boundaries. 20m Contours, road names, rail line, address & titie poinls sourced from Land MAP PRODUCED BY: ORIGINAL MAP SIZE: A4 1 Information NZ. Crown Copyri~t reserved. Pnperty boundanes aca.iracy: +/-1m In urban areas, +/-30m ln Wellington Cit)' Council AUTHOR presto2j Absolutely Positively rural areas_ Census data sourced from Statistics NZ. Postcodes sourced from NZ Post. wakef1eld Street DATE: Wellington City Council Assets, contours. water and drainage ink>rmaOOn shown 1s approximate and must not be used t>r detaHed 101 711012014 Me Hd:e Kl Nneke engineering design. WELLINGTON, NZ REFERENCE: other data has been compded tom a valiety of sources and ils accuracy may vary, butis generally +/- 1rn Cobblestone Park Memorial Park (Te Puke Ahu) Basin Reserve Canal Reserve Prohibited Camping Areas 0 75 150 300 metres , Wellington C.B.D. scale 1 :5,900 Property boundaries, 20m Contours, road names, rail line, address & title points sourced from Land MAP PRODUCED BY: O RIGINAL MAP SIZE: A4 1 Information NZ. Crown Copyright reserved. Property boundaries acooracy: +/-1m in Ufban areas, +/-30m in Wellington Cily council AUTHOR presto2j rural areas_ Census data sourced from Statistics NZ. Postcodes sourced from NZ Post. Absolutely Positively 101 wakefield Street DATE: 711012014 Assets. -

Wellington Mass Transit Independent Review

Wellington Mass Transit Independent Review Let’s Get Wellington Moving Summary Report . October 2017 WELLINGTON MASS TRANSIT INDEPENDENT REVIEW LET'S GET WELLINGTON MOVING WSP LEVEL 9, ZURICH HOUSE 21 QUEEN STREET AUCKLAND 1010 PO BOX 3935 SHORTLAND STREET, AUCKLAND 1140 TEL: +64 9 377 9941 FAX: +64 9 377 9946 WSP.COM REV DATE DETAILS A 29/08/2017 Preliminary Draft B 16/10/2017 Final NAME DATE SIGNATURE Prepared by: R. Jounila 16/10/2017 Reviewed by: T. Cuthbert 16/10/2017 16/10/2017 Approved by: D. McCoy This document may contain confidential and legally privileged information, neither of which are intended to be waived, and must be used only for its intended purpose. Any unauthorised copying, dissemination or use in any form or by any means other than by the addressee, is strictly prohibited. If you have received this document in error or by any means other than as authorised addressee, please notify us immediately and we will arrange for its return to us. OUR REF: 153717A-ITP-REP-001 - WMT SUMMARY REPORT V2 16-10-17 FINAL OCTOBER 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................. III 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Overview ................................................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose of this Review ..................................................................... 1 1.3 Previous Reference Studies .......................................................... -

Attitudes Towards Smoking in Wellington Report on the 2015 Smoke-Free Survey

Attitudes towards smoking in Wellington Report on the 2015 smoke-free survey WCC Research and Evaluation team 1 Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 Aim .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Method ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Analysis ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Sample................................................................................................................................................... 10 Findings ................................................................................................................................................. 13 Awareness amongst population of current smoke-free locations ................................................... 13 Attitudes towards smoking ............................................................................................................... 18 Smoking status preferences for different locations ......................................................................... 22 Comments on additional areas preferred to be smoke-free ........................................................ 27 -

Dads Embracing School Life

Police find Pupil cycles forgotten 1600km for treasures P3 playground P6 WellingtonianThe Thursday, December 1, 2016 thewellingtonian.co.nz Members of the Lyall Bay Dads Group manning the barbecue at the free fair event. From right: Sloane McPhee, Darrell Doig, Dan Perry and Steve Boggs. EMMA DUNLOP-BENNETT Dads embracing school life RUBY MACANDREW school mums ‘‘seemed to know lish a club and host fortnightly ment of all the people in the com- and Chait said he fielded several each other and be quite well- get-togethers. munity - dads included. We inquiries from other dads keen to A community event has helped connected’’, but the same couldn’t ‘‘It’s about getting the dads wanted to tap into that and join join the group and help out the shine a light on the hard work a be said for the dads. involved and connected to learn the dots really.’’ school. group of dads from Lyall Bay ‘‘There were very few dads more about who your neighbours The group had since expanded ‘‘This is not a fundraiser or School has been doing to be more around the school and the ones are and through that become their offerings, including the way to make money – our involved. that did come were all heads more involved in the school.’’ establishment of a touch team motivations in doing this are only After 18 months the ranks of down, drop their kids off and go. From the initial meeting, inter- with 16 members. to bring our local community the Lyall Bay Dads Club have ‘‘It occurred to us that a lot of est in the collective snowballed, An example of the way the closer together.’’ been growing exponentially, and the dads didn’t get to do drop-offs which Chait said was a testament group gets involved is the large- For now, Chait planned to keep they have become a mainstay in that often and the ones that did to the need for dads to be scale fair they recently organised the group’s membership exclus- the school community. -

Topics 10 and 11 – Supplementary Gwrc Summary Statement

TOPICS 10 AND 11 – SUPPLEMENTARY GWRC SUMMARY STATEMENT Heritage policy P46, Civic Trust wharves, and P132/P142 Lambton Harbour Area 1 This supplementary statement relates to three related appeals that were initially addressed in summary statements 10 (Issues 2 and 4) and 11 (Issue 4). GWRC Provision Appellants Summary of appellant’s Section 274 parties and Appeal relief sought position: Support (S) or point Ref. Oppose (O) or Neutral (N) A016/024 Policy P132: Minister of Reconcile policies P132 and Wellington International Functional need Conservation P142 by either: Airport Ltd (O) and efficient use 1. Making the Lambton CentrePort (S) and Harbour Area subject to Site 10 Redevelopment LP paragraphs (e) – (h) in P132 Policy P142 (O) (which relate to using Lambton minimum area necessary, Wellington Fish and Game Harbour Area making available for Council (S) appropriate public or multiple Royal Forest and Bird (S) use, removing structures when redundant and Kainga Ora Homes and concentrating development Communities (O) locations where practicable) Wellington Civic Trust (S) and/or; 2. Confining the exclusion of the Lambton Harbour Area from P132 to parts of the Lambton Harbour Area where redevelopment of existing structures is contemplated, such as the existing “finger wharves” in the northern part of the Lambton Harbour Area. A009/005 Policy P46: CentrePort Add the following sub-clauses Heritage New Zealand Managing and notes at the end of Policy Pouhere Taonga (O) adverse effects P46: Wellington Civic Trust (O) on sites with (i) the use, development, significant The Oil Companies - Z operation, maintenance and historic heritage Energy Limited, BP Oil NZ upgrade of regionally value Ltd and Mobil Oil NZ Ltd (N) significant infrastructure is provided for; StraitNZ Bluebridge Ltd (S) (j) appropriate use and South Wairarapa District development in the Lambton Council (S) Harbour Area (Northern Rangitāne (O) Zone) is enabled. -

We Ington Region

Weington region Events Guide December 2014 - March 2015 Family friendly events Keep up to date at: gw.govt.nz/summer-cycling Cycling in the City 15 Miramar Ciclovia 2 Dec 6 Wellington Wellington WORD Bike-a-Palooza 15 Love to Roll 7 Wainuiomata Wellington Beginners Bike Fix-Up 18 Go By Bike Day 7 Wellington Lower Hutt Summer is the perfect time to dust off your bike and ride to work or 14 Beginners Mountain Biking Grupetto Ride to Work explore the Wellington region’s great scenery. Whether it’s coastal roads, Wellington 20 Newtown rural roads or off road along a scenic trail, you’ll find something to suit. 21 Bike Skills 101 There are lots of opportunities to get out and have some fun at family Beginners Bike Fix-Up Petone friendly events this summer - you’ll find details for events to suit all ages Jan 24 Wellington and abilities inside this guide, along with tips on how to negotiate traffic safely and links to useful cycling information. Pencarrow Bike Ride Mar 1 Bike the Trail 25 Eastbourne Hutt Valley To find out more please visit: Family Bike Skills Intro 7 Karapoti Classic www.gw.govt.nz/summer-cycling 31 Wellington Wellington Cycling in the City 7 Wellington Rimutaka Rail Trail Check out the Feb 7 Upper Hutt Miramar Ciclovia 3 8 Wellington region’s best riding Cycling in the City 7 Wellington 14 Frocks on Bikes Frocknic locations! Wairarapa Miramar Ciclovia 1 8 Wellington 14 Big Bike Fix-Up Wellington Go By Bike Day 11 Wellington Cycling Amongst Giants 15 Wainuiomata Go By Bike Day 11 Käpiti Bike Skills 101 21 Porirua 14-22 Huri Huri Bike Festival Folding Bike Ride Wairarapa 22 Käpiti Advance Stop Boxes Advance Stop Boxes are painted green and are on many Wellington City streets. -

Before the Queenstown Lakes District Council

BEFORE THE QUEENSTOWN LAKES DISTRICT COUNCIL IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER OF Queenstown Lakes Proposed District Plan – Chapter 13 – Wanaka Town Centre Zone STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF LOUISE WRIGHT OF ASSEMBLY ARCHITECTS ON BEHALF OF SUBMITTER 240 – Gem Lake Limited 17 November 2016 Accompanying Document: Wanaka Town Centre: Submission on Proposed Queenstown Lakes District Plan by Assembly Architects Ltd Introduction 1. My name is Louise Jayne Hikihiki Wright. I am a Registered Architect. I hold a Bachelor of Architecture (First Class Honours) from Victoria University of Wellington, 2001. I am a member of the New Zealand Registered Architects Board, the New Zealand Institute of Architects Awards Advisory Board, and the Jack’s Point Design Review Board. I am the 2017 Convenor of the New Zealand Institute of Architects national awards programme. 2. I am a design director of Assembly Architects Limited, an Arrowtown based architecture practice that I established with Justin Wright, Registered Architect in 2005. The practice designs residential, commercial and public architecture. The practice was awarded a New Zealand Architecture award for the public and commercial development at Wellington Zoo, and architecture, design and property awards for the design of the Britomart Showcases in the Britomart precinct in Auckland. Assembly Architects are currently designing a proposed 36 room hotel in Wanaka, and the Stackbrae subdivision in Cardrona Valley Road, Wanaka. 3. Prior to establishing Assembly Architects