Analyzing the Relationship Between Live Music Performances and Violence in Madison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nathan Mensah MAMT Thesis.Pdf

Preparing for the future: A description of client music preferences and musical preparedness of music therapists by Nathan A. Mensah, MT-BC A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For the Master of Arts Degree Master of Arts in Music Therapy Program in the Departments of Graduate Studies and Music and Theatre Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana May, 2019 Abstract Music therapists often use client-preferred music in order to build rapport with clients, decrease their anxiety, increase relaxation, and increase overall efficacy of music interventions. The American Music Therapy Association states music therapists are required to play a wide variety of genres for use in sessions. Client’s musical tastes have grown diverse due to music streaming, and some music therapists may not have the musical skills necessary to recreate these styles in sessions. Currently, there is no data to show which genres and music styles are most commonly requested by their clients, or data to show which genres music therapists feel musically prepared or unprepared to use in sessions. A survey was used to collect data from board-certified music therapists to ask about which genres their clients most commonly request, as well as which genres they feel musically prepared using in sessions. The survey’s findings were that client’s most frequently requested Children’s, Classic Country, Classic Rock, Gospel, Hymn, Oldies, and Pop Music. Respondents reported to feeling most musically prepared to use genres that were most frequently requested by their clients. Music therapists reported not feeling musically prepared to use genres associated with World Music cultures or genres requiring use of electronic or synth- based instruments such as Bachata, EDM, Funk, Heavy Metal, Hip Hop/Rap, J-Pop, K-Pop, Latin Hip Hop/Latin Rap, Latin Pop, Merengue, Punk, Reggaeton, Salsa, Ska, Trap, and Video Game Music. -

Queens of Consciousness & Sex-Radicalism in Hip-Hop

Queens of Consciousness & Sex-Radicalism in Hip-Hop: On Erykah Badu & The Notorious K.I.M. by Greg Thomas, Ph.D. English Department Syracuse University Greg Thomas ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor in the English Department at Syracuse University. His interests include Pan-Africanism, Hip-Hop and Black radical traditions. He is author of The Sexual Demon of Colonial Power: Pan-African Embodiment and Erotic Schemes of Empire (Indiana University Press, 2007). He is also editor of the e-journal, Proud Flesh: New Afrikan Journal of Culture, Politics & Consciousness. Abstract This article is a study of sex, politics and lyrical literature across what could be called “Hip-Hop & Hip-Hop Soul.” It champions the concept “sexual consciousness” against popular and academic assumptions that construe “sexuality” and “consciousness” to be antithetical--in the tradition of “the mind/body split” of the white bourgeois West. An alternative, radical articulation of consciousness with an alternative, radical politics of gender and sexuality is located in the musical writings of two contemporary “iconic” figures: Lil’ Kim of “Hip-Hop” and Erykah Badu of “Neo-Soul.” Underscoring continuities between these author-figures, one of whom is coded as an icon of “sexuality (without consciousness),” conventionally, and the other as an icon of “consciousness (without sexuality),” I show how Black popular music is a space where radical sexual identities and epistemic politics are innovated out of vibrant African/Diasporic traditions. 23 The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 1, no. 7, March 2007 The reputed “Father of African Cinema,” Ousmane Sembène is perhaps ironically famous for what we can call his sexual consciousness, a consciousness of the politics of sex or gender and sexuality, in his radical productions of Black independent film. -

Lab Data.Pages

Day 1 The Smiths Alternative Rock 1 6:48 Death Day Dark Wave 1 4:56 The KVB Dark Wave 1 4:11 Suuns Dark Wave 6 35:00 Tropic of Cancer Dark Wave 2 8:09 DIIV Indie Rock 1 3:43 HTRK Indie Rock 9 40:35 TV On The Radio Indie Rock 1 3:26 Warpaint Indie Rock 19 110:47 Joy Division Post-Punk 1 3:54 Lebanon Hanover Post-Punk 1 4:53 My Bloody Valentine Post-Punk 1 6:59 The Soft Moon Post-Punk 1 3:14 Sonic Youth Post-Punk 1 4:08 18+ R&B 6 21:46 Massive Attack Trip Hop 2 11:41 Trip-Hop 11:41 Indie Rock 158:31 R&B 21:46 Post-Punk 22:15 Dark Wave 52:16 Alternative Rock 6:48 Day 2 Blonde Redhead Alternative Rock 1 5:19 Mazzy Star Alternative Rock 1 4:51 Pixies Alternative Rock 1 3:31 Radiohead Alternative Rock 1 3:54 The Smashing Alternative Rock 1 4:26 Pumpkins The Stone Roses Alternative Rock 1 4:53 Alabama Shakes Blues Rock 3 12:05 Suuns Dark Wave 2 9:37 Tropic of Cancer Dark Wave 1 3:48 Com Truise Electronic 2 7:29 Les Sins Electronic 1 5:18 A Tribe Called Quest Hip Hop 1 4:04 Best Coast Indie Pop 1 2:07 The Drums Indie Pop 2 6:48 Future Islands Indie Pop 1 3:46 The Go! Team Indie Pop 1 4:15 Mr Twin Sister Indie Pop 3 12:27 Toro y Moi Indie Pop 1 2:28 Twin Sister Indie Pop 2 7:21 Washed Out Indie Pop 1 3:15 The xx Indie Pop 1 2:57 Blood Orange Indie Rock 6 27:34 Cherry Glazerr Indie Rock 6 21:14 Deerhunter Indie Rock 2 11:42 Destroyer Indie Rock 1 6:18 DIIV Indie Rock 1 3:33 Kurt Vile Indie Rock 1 6:19 Real Estate Indie Rock 2 10:38 The Soft Pack Indie Rock 1 3:52 Warpaint Indie Rock 1 4:45 The Jesus and Mary Post-Punk 1 3:02 Chain Joy Division Post-Punk -

(Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul Meets Jazzy Blues

Artscape Entertainment Resource Guide 2013 Band Name Genre Website Email Phone Number Allie & The Cats (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul meets Jazzy Blues http://www.alliemariemusic.com [email protected] 4109916973 Balti Mare Balkan Gypsy Brass http://www.facebook.com/baltimare [email protected] 4109633799 Basement Instinct (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Alternative Rock https://www.facebook.com/basementinstinctband [email protected] 4437038941 Bearstronaut pop http://bearstronaut.com [email protected] 8609124857 Big Sur Alternative Melodic Rock http://www.bigsurrock.com [email protected] 3015931778 Billy Wilkins Jazz/Rock https://soundcloud.com/billy-wilkins-1 [email protected] 4103696360 Blizz Hip Hop http://www.hulkshare.com/Blizz [email protected] 4439860731 Boozey R&B and Hip Hop http://Boozeyonline.com [email protected] Braunsy Brooks & Worship Kulture Christian http://www.bbworshipkulture.com [email protected] 8284554010 Brittanie Thomas Music Soul/R&B http://www.brittaniethomas.com [email protected] 4433608985 Brothers Kardell Experimental electronic pop metal hip-hop http://www.soundcloud.com/brotherskardell [email protected] 2022862623 Buddah Bass Hip-Hop/Pop http://Buddahbass.bandcamp.com [email protected] 3365779559 Bumpin Uglies Reggae/Ska http://www.bumpinugliesmusic.com [email protected] 4102793613 Children of a Vivid Eden Alternative rock http://www.facebook.com/c.o.v.e.rock [email protected] 4436324130 Chris Reynolds and -

Rock Music Is a Genre of Popular Music That Entered the Mainstream in the 1950S

Rock music is a genre of popular music that entered the mainstream in the 1950s. It has its roots in 1940s and 1950s rock and roll, rhythm and blues, country music and also drew on folk music, jazz and classical music. The sound of rock often revolves around the electric guitar, a back beat laid down by a rhythm section of electric bass guitar, drums, and keyboard instruments such as Hammond organ, piano, or, since the 1970s, synthesizers. Along with the guitar or keyboards, saxophone and blues-style harmonica are sometimes used as soloing instruments. In its "purest form", it "has three chords, a strong, insistent back beat, and a catchy melody."[1] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, rock music developed different subgenres. When it was blended with folk music it created folk rock, with blues to create blues-rock and with jazz, to create jazz-rock fusion. In the 1970s, rock incorporated influences from soul, funk, and Latin music. Also in the 1970s, rock developed a number of subgenres, such as soft rock, glam rock, heavy metal, hard rock, progressive rock, and punk rock. Rock subgenres that emerged in the 1980s included new wave, hardcore punk and alternative rock. In the 1990s, rock subgenres included grunge, Britpop, indie rock, and nu metal. A group of musicians specializing in rock music is called a rock band or rock group. Many rock groups consist of an electric guitarist, lead singer, bass guitarist, and a drummer, forming a quartet. Some groups omit one or more of these roles or utilize a lead singer who plays an instrument while singing, sometimes forming a trio or duo; others include additional musicians such as one or two rhythm guitarists or a keyboardist. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

"Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2010 "Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers." James L. Wright UTK, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wright, James L., ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers.". " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/760 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. Wright entitled ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Suzaanne B. Kurth, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Robert Emmet Jones; Hoan Bui; Debora Baldwin Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. -

Distant Music: Recorded Music, Manners, and American Identity Jacklyn Attaway

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Distant Music: Recorded Music, Manners, and American Identity Jacklyn Attaway Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DISTANT MUSIC: RECORDED MUSIC, MANNERS, AND AMERICAN IDENTITY By JACKLYN ATTAWAY A Thesis submitted to the American and Florida Studies Program in the Department of Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2012 Jacklyn Attaway defended this thesis on November 5, 2012 The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry J. Faulk Professor Directing Thesis Neil Jumonville Committee Member Jerrilyn McGregory Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I dedicate this to Stuart Fletcher, a true heir-ethnographer who exposed me to the deepest wells of cultural memory in the recorded music format; Shawn Christy, for perking my interest in the musicians who exhibited the hauntological aesthetic effect; and to all the members of WVFS Tallahassee, 89.7 FM—without V89, I probably would not have ever written about music. Thank you all so much for the knowledge, love, and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Barry J. Faulk, Dr. Neil Jumonville, Dr. Jerrilyn McGregory, Leon Anderson, Dr. John Fenstermaker, Peggy Wright-Cleveland, Ben Yadon, Audrey Langham, Andrew Childs, Micah Vandegrift, Nicholas Yanes, Mara Ginnane, Jason Gibson, Stuart Fletcher, Dr. -

Digginmelbourne-May-2018-Web.Pdf

SECONDHAND VINYL LPs/EPs/45s MELBOURNE CBD NEW VINYL / CDs / DVDs & CITY FRINGE BOOKS, DJ ACCESSORIES & MORE FIRST STOP > FLINDERS STREET STATION PBS / RRR MEMBER DISCOUNTS Swanston 1 WAX MUSEUM Flinders Ln 2 Campbell Arcade, Degraves St, Melbourne (Enter via Subway) Degraves (03) 9663 6310 | [email protected] Elizabeth St www.waxmuseumrecords.com.au Mon-Fri: 11am-6pm | Sat: 11am-5pm | Sunday & Public Holidays: Closed It’s all about the beats! Specialising in Hip-hop and future beat with a dash of Flinders St Flinders St. house, techno and drum n bass. We also stock a healthy range of 70s, 80s, 90s jazz, funk, soul, rock & pop, disco & boogie, reggae & dancehall, afro beat. Elizabeth 2 P OFF THE HIP Collins St Queen St Basement Level 381 Flinders Lane, Melbourne (via Tavistock Pl) (03) 9621 2044 | 0402 027 137 | [email protected] Flinders Ln facebook.com/offthehiprecords Tues: 11am-2.30pm | Wed: 10am-4pm | Thurs: 10am-6pm | Fri: 11am-7pm Flinders St Sat: 11am-5pm | Sun-Mon: Closed. Lots of new and second hand vinyl: garage rock, powerpop, blues, soul, hard rock, psychedelia, surf, beat and everything in-between. Imports and local releases. Swanston 3 BASEMENT DISCS PR Little Collins St Basement, 24 Block Place, Melbourne Block Pl (03) 9654 1110 | [email protected] Elizabeth St St www.basementdiscs.com.au Collins St Mon-Fri: 10am-6pm | Sat: 10am-5pm | Sun: 11am-5pm. Specialising in rock, pop, country, folk, blues, jazz, soul, funk & world. New Vinyl, CD and DVD with a strong focus on new releases, back catalogue, indie and hard-to-find titles, fresh Flinders Ln stock arriving daily. -

Computational Models of Music Similarity and Their Applications In

DISSERTATION Computational Models of Music Similarity and their Application in Music Information Retrieval ausgef¨uhrt zum Zwecke der Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der technischen Wissenschaften unter der Leitung von Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. techn. Gerhard Widmer Institut f¨urComputational Perception Johannes Kepler Universit¨atLinz eingereicht an der Technischen Universit¨at Wien Fakult¨atf¨urInformatik von Elias Pampalk Matrikelnummer: 9625173 Eglseegasse 10A, 1120 Wien Wien, M¨arz 2006 Kurzfassung Die Zielsetzung dieser Dissertation ist die Entwicklung von Methoden zur Unterst¨utzung von Anwendern beim Zugriff auf und bei der Entdeckung von Musik. Der Hauptteil besteht aus zwei Kapiteln. Kapitel 2 gibt eine Einf¨uhrung in berechenbare Modelle von Musik¨ahnlich- keit. Zudem wird die Optimierung der Kombination verschiedener Ans¨atze beschrieben und die gr¨oßte bisher publizierte Evaluierung von Musik¨ahnlich- keitsmassen pr¨asentiert. Die beste Kombination schneidet in den meisten Evaluierungskategorien signifikant besser ab als die Ausgangsmethode. Beson- dere Vorkehrungen wurden getroffen um Overfitting zu vermeiden. Um eine Gegenprobe zu den Ergebnissen der Genreklassifikation-basierten Evaluierung zu machen, wurde ein H¨ortest durchgef¨uhrt.Die Ergebnisse vom Test best¨a- tigen, dass Genre-basierte Evaluierungen angemessen sind um effizient große Parameterr¨aume zu evaluieren. Kapitel 2 endet mit Empfehlungen bez¨uglich der Verwendung von Ahnlichkeitsmaßen.¨ Kapitel 3 beschreibt drei Anwendungen von solchen Ahnlichkeitsmassen.¨ Die erste Anwendung demonstriert wie Musiksammlungen organisiert and visualisiert werden k¨onnen,so dass die Anwender den Ahnlichkeitsaspekt,¨ der sie interessiert, kontrollieren k¨onnen. Die zweite Anwendung demon- striert, wie auf der K¨unstlerebene Musiksammlungen hierarchisch in sich ¨uberlappende Gruppen organisiert werden k¨onnen. Diese Gruppen werden mittels W¨orter von Webseiten zusammengefasst, welche mit den K¨unstlern assoziiert sind. -

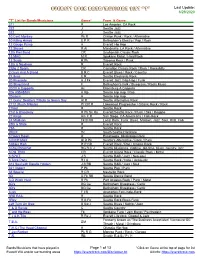

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality.