Harecastle Tunnels & Burslem Branch Canal Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Harecastle Tunnel the Harecastle Tunnel

© www.talke.info 2008 The Harecastle tunnel Most of this section is quoted from Appelby’s Canal tunnels in England and Wales and Philip Leese’s Kidsgrove times on which I could not possibly improve. Talke’s place as centre of transport with as many as twenty teams of mule drivers stopping at the inns was not to last. The first blow was the opening of the Harecastle tunnel, a remarkable feat of engineering by Thomas Telford and James Brindley. Brindley’s first t tunnel was opened in 1777, five years after the engineer’s death. It is 2,897 feet long, 8feet 6inches wide, and in use until 1918. The second ‘Telford’ tunnel, opened in 1827 and is still in use today, it is 2,929 yards long and much wider. The canals orange colour can be attributed to local geology (iron ore) and the canals clay lining , (a technique called puddling) used to stop the water leaking out , rather than any pollution. James Brindley started work on Harecastle One on 27 June 1766, partly at the urging of local potter Josiah Wedgewood, who needed a safe and cheap means to transport coal to the kilns. ‘In the event, the tunnel took eleven years to build, during which time Brindley died and was replaced as chief engineer by his brother in law, Hugh Henshall. Harecastle had presented all manner of problems, including quicksand, hard rock outcrops, springs and even deadly methane gas, as well as resident engineers and contractors taking advantage of the lack of close supervision by the over- stretched Brindley.’ The tunnel itself was very narrow, much like the mining tunnels at Worsley,and during construction side tunnels were dug to exploit seams of coal (which were also arched and bricked to the same height as the Harecastle I Kidsgrove portal © www.talke.info 2008 main tunnel).’ One local legend states that there is an underground wharf just within the Kidsgrove entrance to load this coal. -

James Brindley ( 1716 - 1772 )

1 James Brindley ( 1716 - 1772 ) These notes are designed to help you with homework and other pro- jects. It will help you to find out: About James Brindley’s early life How he became a famous canal engineer His ideas and inventions. My mum taught me at home. I became the greatest canal engineer of my day! You can see this statue canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers of James Brindley at Coventry Basin 2 Mr Fixit The spokes should James Brindley was born 300 years ago point inwards, not near Buxton, in Derbyshire. As a boy he outwards, you banana! loved building toy mills and trying them out in the wind and water. Later, James was apprenticed to a master mill- and Oops! wheelwright. It didn’t start off well. He built a cartwheel with spokes facing outwards instead of inwards! Gradually, James became known as someone who could fix any machinery. When his master died he moved to Leek in Staffordshire, to start a new business there. canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers 3 The Bridgewater Canal The Bridgwater Canal was first called James’s business grew. He worked the Duke’s Canal on all kinds of machinery driven by water, wind and steam. The Duke of Worsley Bridgewater, who owned coal mines RUNCORN Barton coal fields near Manchester, heard about him. Aqueduct ell Irw R er Coal was used i iv ve y R to heat everything r M erse R R Mersey i from houses to v T he e Duk r e’s Manchester furnaces - so Can W al e everyone wanted a v cheap coal. -

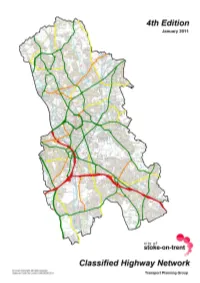

Classified Highway Network Document 4.00 Jan11

City of Stoke-on-Trent Classified Highway Network January 2011 Version 4.00 INTRODUCTION This document supersedes Version 3.01, May 2008. The information within this document describes the Classified Highway Network as of January 2011. The document illustrates and lists all classified roads within Stoke-on-Trent including all A (trunk and principal), B and C roads. It also defines the Strategic Highway and Primary Route Networks. For enquiries or further information please contact: Transport Planning Group City Renewal Stoke-on-Trent City Council PO Box 630 Civic Centre Glebe Street Stoke-on-Trent ST4 1RF T: 01782 232149 E: [email protected] - 1 - City of Stoke-on-Trent Classified Highway Network January 2011 Version 4.00 - 2 - City of Stoke-on-Trent Classified Highway Network January 2011 Version 4.00 SCHEDULE OF CLASSIFIED ROADS Principal Roads – Sorted by Number Road Number Name Road Number Name A34 NEWCASTLE ROAD A5035 TRENTHAM ROAD A34 STONE ROAD A52 BUCKNALL ROAD A50 HIGH STREET A52 CAMPBELL PLACE A50 HIGH STREET (SANDYFORD) A52 CHURCH STREET A50 KIDSGROVE ROAD A52 CITY ROAD A50 KING STREET A52 COPELAND STREET A50 LICHFIELD STREET A52 ELENORA STREET A50 POTTERIES WAY A52 FLEMING ROAD A50 SCOTIA ROAD A52 GLEBE STREET A50 SWAN SQUARE A52 HARTSHILL ROAD A50 VALE PLACE A52 LEEK ROAD A50 VICTORIA PLACE A52 LIVERPOOL ROAD A50 A50 (VICTORIA PLACE LINK) A52 LONDON ROAD A50 VICTORIA ROAD A52 LONSDALE STREET A50 WATERLOO ROAD A52 SHELTON OLD ROAD A50 WEDGWOOD PLACE A52 WERRINGTON ROAD A50 WEDGWOOD STREET A52 WOODHOUSE STREET A50(T) -

Birmingham Canal Network Fact Sheet Building Cost Locks

Birmingham Canal Network Fact Sheet Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) is a network of canals connecting Birmingham, Length: Wolverhampton and the eastern part of the 186 miles Black Country. One of the most intricate canal networks the Building cost world, the Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) £50,ooo system, adds up to 1 00 miles over 1 3 canals. History Engineer: The canal network was built over a 100 year James Brindley period starting from 1 772. The canals were the life-blood of Victorian Birmingham and at their height they were so busy that gas lighting was Locks: installed to enable round-the-clock operation. 216 Over eight and a half million tons a year was being carried at the end of the nineteenth century. The canal network serviced the canal Tunnels: side factories and carried raw materials in and products out to the country and world. Map courtesy of Map data 0201 6 Google - attribution Photo courtesy of ahisgett licence - attribution twinkl.co.uk Grand Union Canal Fact Sheet The Grand Union Canal is the longest canal in the UK at 286 miles long and runs from London Length: to Birmingham. 286 miles History The canal was not originally constructed as one canal; it is the result of various canals being amalgamated and Building cost connected during the early 19th century. The canal £772,ooo passes through varied scenery from rolling countryside to industrial towns and cities. Locks: The canal faced competition from the railways 1 66 in the second half of the 19th century. Improvements in roads and vehicle technology in the early part of the 20th century meant that Tunnels: 6 the lorry was also becoming a threat to the canals. -

James Brindley (1716 - 27 September 1772)

James Brindley (1716 - 27 September 1772) James Brindley, an English engineer, was born in Tunstead, Derbyshire, and lived much of his life in Leek, Staffordshire. He became one of the most notable engineers of the 18th century. Born into a family of yeoman farmers and craftsmen in the then isolated Peak District, he received little formal education but was educated at home by his mother. At 17 he commences a seven-year apprenticeship as carpenter and millwright with Abraham Bennett of Gurnett, Sutton, near to Macclesfield, Cheshire. He was initially called a fool and bungler by his master and the other men. However a year or so into his apprenticeship he was being asked for by name by local mill owners when repairs were required, often in preference to the master himself. An example of Brindley's ability and character is his response to a disastrous undertaking by Abraham Bennett: Bennett was employed to create machinery for a new paper-mill, by the River Dane at Wildboarclough, Cheshire. He used the machinery in two other mills, as his model for Wildboarclough, but his drunkenness ensured he had insufficient practical information to do the job. However, Bennett set his men to work unwilling to forego the financial rewards of such a job. The assembled machinery would neither fit nor work and it was clear that Bennett was not up to the job. But Bennett and his men persevered making no satisfactory progress. Bennett was unwilling to admit to his own incompetence as a mechanic and feared for his reputation and thereby his future employment prospects. -

Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) Is a Knotty Network of Canals Linking Towns and Country Together

l Birmingham Cana This fact file is designed to help you with avigations homework and other projects. N It will help you: • Find out who built the BCN FACT FILE • Discover all about your local canal • See where it goes Today, the BCN has 100 miles of navigable canals Cool canals Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) is a knotty network of canals linking towns and country together. At its centre, Gas Street Basin is busy with boaters, walkers and cyclists. The BCN is one But there are also secret branch canals just waiting to of the most complicated be explored! canal networks in the world! © Canal & River Trust Charity Commission no. 1146792 1 canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers mingham Canal ir CHASEWATER B ‘Flight of 21 Locks’ RESERVOIR avigations Wolverhampton N 1 Coventry Canal Shropshire Union Canal Which is Daw End Wyrley & Canal your nearest canal? Essington Canal What’s it called? Staffs & FAZELEY Worcs Canal 1 Walsall Art Gal Chimney Bridge, lery WALSALL 7 Tame Valley Canal Walsall Canal Rushall 7 WOLVERHAMPTON Canal 2 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal BCN WEDNESBURY Main Line ‘Legging’ through Dudley Tunnel BRADLEY 2 5 Tame Valley Canal Toll Office 5 DUDLEY 4 gham Roundhouse A powerhouse Birmin Farmers Bridge Locks Two hundred years Stourbridge 6 ago, at the height of its Canal SMETHWICK Gas Street Basin, Dudley 6 Birmingham importance, the BCN had Canals BIRMINGHAM 3 160 miles (257 km) of canals, 1 and 2 4 3 206 locks, 17 pumping S stations, 7 tunnels and to STOURBRIDGE urb Grand Union ridg 6 reservoirs. e Gla Worcs & ss Cone Birmingham Canal Canal Galton Valley Pumping Station, Smethwick © Canal & River Trust Charity Commission no. -

Brindley Gates, Safety Gates, Stop Gates and Stop Planks Introduction

Occasional Paper 128 – Brindley gates, safety gates, stop gates and stop planks Introduction: In his book Lives of the Engineers Samuel Smiles advises As one of the great objections made to the construction of the canal had been the danger threatened to the surrounding districts by the bursting of the embankments, Brindley made it his object to provide against the occurrence of such an accident by an ingenious expedient. He refers to the Duke of Bridgewater’s Canal built in the 1760s to carry coal from his mines at Worsley to Manchester. Some twenty years after the opening of the Duke’s canal, John Phillips, in his “Phillips Inland Navigation” writes that there were many stops, or floodgates, designed to automatically shut in the event of a breach built into the Duke’s canal. There are suggestions that some of the other early canals were also built with these automatic gates, now generally known as a “Brindley Gates, after the Bridgewater Canal’s engineer, James Brindley but, so far, no positive evidence has come to light. However, recent excavations during several canal restoration projects have identified a derivative of the automatic gate which was manually operated and will be discussed later. The Brindley Gate, (or Safety Gate): Historical Information There is no illustration in Smiles’ volume but a sketch and description of such an expedient can be found in The Cyclopaedia or Dictionary of Arts, Science and Literature by Abraham Rees. His sketch, redrawn for clarity as Fig 1, is explained as follows: Represents the top of the wall, or AB height of the towing path under a bridge. -

The International Canal Monuments List

International Canal Monuments List 1 The International Canal Monuments List Preface This list has been prepared under the auspices of TICCIH (The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage) as one of a series of industry-by-industry lists for use by ICOMOS (the International Council on Monuments and Sites) in providing the World Heritage Committee with a list of "waterways" sites recommended as being of international significance. This is not a sum of proposals from each individual country, nor does it make any formal proposals for inscription on the World Heritage List. It merely attempts to assist the Committee by trying to arrive at a consensus of "expert" opinion on what significant sites, monuments, landscapes, and transport lines and corridors exist. This is part of the Global Strategy designed to identify monuments and sites in categories that are under-represented on the World Heritage List. This list is mainly concerned with waterways whose primary aim was navigation and with the monuments that formed each line of waterway. 2 International Canal Monuments List Introduction Internationally significant waterways might be considered for World Heritage listing by conforming with one of four monument types: 1 Individually significant structures or monuments along the line of a canal or waterway; 2 Integrated industrial areas, either manufacturing or extractive, which contain canals as an essential part of the industrial landscape; 3 Heritage transportation canal corridors, where significant lengths of individual waterways and their infrastructure are considered of importance as a particular type of cultural landscape. 4 Historic canal lines (largely confined to the line of the waterway itself) where the surrounding cultural landscape is not necessarily largely, or wholly, a creation of canal transport. -

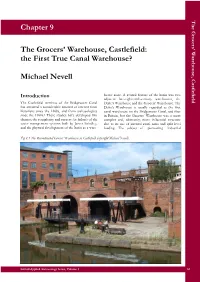

Chapter 9 Chapter Salford Applied Archaeology Series, Volume 1 Salford Applied

Castlefield The Grocers’ Warehouse, Chapter 9 The Grocers’ Warehouse, Castlefield: the First True Canal Warehouse? Michael Nevell Introduction house zone. A central feature of the basin was two adjacent late-eighteenth-century warehouses, the The Castlefield terminus of the Bridgewater Canal Duke’s Warehouse and the Grocers’ Warehouse. The has attracted a considerable amount of interest from Duke’s Warehouse is usually regarded as the first historians since the 1860s, and from archaeologists canal warehouse on the Bridgewater Canal, and thus since the 1960s.1 These studies have developed two in Britain, but the Grocers’ Warehouse was a more themes; the complexity and success (or failure) of the complex and, ultimately, more influential structure water management systems built by James Brindley, due to its use of internal canal arms and split-level and the physical development of the basin as a ware- loading. The subject of pioneering industrial Fig 9.1 The Reconstructed Grocers’ Warehouse in Castlefield (copyright Michael Nevell). Salford Applied Archaeology Series, Volume 1 83 Castlefield The Grocers’ Warehouse, archaeological recording and excavation in 1960, and detailed survey and reconstruction in the mid-1980s, the ruins of this warehouse form the earliest surviv- ing building in the terminus. Origins of the Coal Tunnel and Castle Quay Although there are two studies of the Grocers’ ware- house, the first by V I Tomlinson published in 1961 and the second by Cyril Boucher published in 1989,2 the re-cataloguing of the Bridgewater archives held by Salford City Council and the University of Sal- Fig 9.3: The southern end of the 1760s coal tunnel by the ford, and further recording of the ruins since 1989, Grocers’ Warehouse (copyright GMAU). -

Wolverhampton Locks Walking Trail a Walk Along

Wolverhampton locks Walking Trail A walk along the 21 locks Wolverhampton www.wolverhampton.gov.uk A walk along the 21 locks A Wolverhampton 6 6 Walking is an excellent form of 4 gentle exercise. It not only improves your fitness but also your sense of well-being. By walking this trail you will have: Walked (one way) 1 3/4 miles (2.8 km), taken approximately 3,500 steps and burnt 175 calories The Canal & River Trust owns and manages over 2,000 miles of canals and rivers in England and Wales. For more information about canal based activities visit www.canalrivertrust.org.uk or email [email protected] 1 21 locks walk The Trail starts at Broad Street Basin which is easily accessible from the town centre. It ends at Aldersley Junction. You may return to Welcome Wolverhampton Town Centre using local bus services. Bus routes in the vicinity of the finish The Wolverhampton Locks Trail takes you on a are marked on the trail plan; alternatively retrace walk, (or a cycle ride or boat trip), along the the route of the trail. Birmingham Main Line Canal to highlight features of interest. Bus users can contact 0121 200 2700 regarding bus services. The conservation and enhancement of historic buildings and environments are important objectives of the Council and this trail has been prepared to provide an enjoyable and informative experience for those with an interest Broad Street Basin in the heritage of the City. Broad Street Basin is now a pleasant, quiet The Trail should take about one and a half hours oasis, surrounded by the ring road and railway. -

Histintro V2

Historical introduction to Britain’s waterways The cutting of artificial water channels is documented throughout the known world from pre-Biblical times. In Egypt King Menes constructed a canal around 4000 BC, the same period that Egyptians first used ships with sails on the Nile; by 600 BC the 260 miles between China’s Yellow River and Huai River were linked by the Wild Goose Canal and by 102 BC the River Rhone had been connected with the Mediterranean Sea. The influence of canals, in their loosest definition as man made channels that carry water, upon the development of civilisation itself may be more far reaching than at first appears. The Fertile Crescent, an arc-shaped strip of land running from Syria and Palestine towards the delta of the Euphrates, Tigris and the Nile, is considered the cradle of civilisation but it was only through use of irrigation channels that the land became fertile enough to enable the first great societies to flourish. In Mesopotamia, or ‘the country between two rivers’, agriculture and animal husbandry were the foundations of life. Prior to 7000 BC early Mesopotamians learnt how to use the rivers for their needs and regulated water supply by a series of channels that were dug and filled as necessary depending upon flood or drought conditions. From this it is not too great a leap of faith to envisage the Mesopotamian people also shifting cargo and people by water. Britain was not left wanting in the development of waterways for transport and her history reflects this. The Foss Dyke, connecting the River Witham with the River Trent, is of Roman origin. -

Out and About Barging Between Brindleys

Out and About Barging between Brindleys For this month’s Out and About Dave Martin takes to the water oventry canal basin ought to be a hive of activity. It is a collection of new and well-restored buildings around the terminal arms of the Coventry Canal and could Cbe like thriving Gas Street Basin in neighbouring Birmingham, but it is on the wrong side of the inner ring road. Begun in the 1950s this monument to the motor car turned Coventry city centre into one enormous traffic island just like so many other Midland towns and cities blighted by planners prioritising cars over pedestrians. To reach the canal basin from the city centre today your only choice is to climb and cross an unattractive pedestrian footbridge spanning six lanes of speeding traffic which is clearly sufficient discouragement for many. This is a shame as not only is it worthy of a visit in its own right but it also boasts an excellent bronze statue of the canal engineer James Brindley. Brindley stands larger than life, bending over a desk and looking up towards the ‘Number 1’ bridge which he designed. Under his right hand is, I guess, his note book and spread across the desk top his design drawing for the bridge itself. His is a muscular physical presence. At first glance the desk appears too flimsy to match the man’s vigour but closer inspection reveals it to be not an elegant Georgian drawing room piece but a robust desk made from three planks with single drawer and sturdy legs.