Brindley Gates, Safety Gates, Stop Gates and Stop Planks Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 1999 NUMBER2

C & 0 Canal Association concerned with the conservation of the natural and historical environment of the C&O Canal and the Potomac River Basin VOLUME XXXI June 1999 NUMBER2 The Level Walker Issue As we with good reason emphasize the Level Walker Program in this issue of Along the Towpath, and muster extra strength which will surely be required to support the NPS "Trash in, Trash out" policy, I remind you that it was a level walker that introduced me to the Park in 1970. At that time I was so ignorant about canal matters that I thought, when he told me about being a "level walker", that he had gotten so old and decrepit that he could no longer handle hills and mountains. Needless to say, my 30 years along the towpath since then have provided abundant iilumination and practical experience as Linda and I have picked up trash and reported on conditions along our own three mile level. And I think that there is no more basic program of support for the park than this. I know of course that there are many ways we serve, and some of them more visible and interactive than this. But the scattered, often unseen and unthanked efforts that keep the park neat and attractive from one end to the other: why there is nothing more basic than this to make the towpath attractive to potential users. And we can tell those users who we are, and what we do, and invite them to join us on the level. --Tom Perry Several Months ago, a suggestion was made that an issue of Valley and the Canal, and who are willing to "patrol" a Along the Towpath be dedicated to Level Walkers--hence this section twice a year and report on its condition and its month's theme. -

The Harecastle Tunnel the Harecastle Tunnel

© www.talke.info 2008 The Harecastle tunnel Most of this section is quoted from Appelby’s Canal tunnels in England and Wales and Philip Leese’s Kidsgrove times on which I could not possibly improve. Talke’s place as centre of transport with as many as twenty teams of mule drivers stopping at the inns was not to last. The first blow was the opening of the Harecastle tunnel, a remarkable feat of engineering by Thomas Telford and James Brindley. Brindley’s first t tunnel was opened in 1777, five years after the engineer’s death. It is 2,897 feet long, 8feet 6inches wide, and in use until 1918. The second ‘Telford’ tunnel, opened in 1827 and is still in use today, it is 2,929 yards long and much wider. The canals orange colour can be attributed to local geology (iron ore) and the canals clay lining , (a technique called puddling) used to stop the water leaking out , rather than any pollution. James Brindley started work on Harecastle One on 27 June 1766, partly at the urging of local potter Josiah Wedgewood, who needed a safe and cheap means to transport coal to the kilns. ‘In the event, the tunnel took eleven years to build, during which time Brindley died and was replaced as chief engineer by his brother in law, Hugh Henshall. Harecastle had presented all manner of problems, including quicksand, hard rock outcrops, springs and even deadly methane gas, as well as resident engineers and contractors taking advantage of the lack of close supervision by the over- stretched Brindley.’ The tunnel itself was very narrow, much like the mining tunnels at Worsley,and during construction side tunnels were dug to exploit seams of coal (which were also arched and bricked to the same height as the Harecastle I Kidsgrove portal © www.talke.info 2008 main tunnel).’ One local legend states that there is an underground wharf just within the Kidsgrove entrance to load this coal. -

Strategic Waterway Plan Engagement Prospectus Looking Forward to the Next Ten Years

Strategic Waterway Plan Engagement Prospectus Looking forward to the next ten years South Wales and Severn Waterway Partnership 1 Contents Chairman’s introduction 3 About the Canal & River Trust 4 Our role and objectives 4 Our strategic priorities 5 Our resources 6 Our governance 6 Waterway partnerships 7 The Partnerships in context 7 What are the Partnerships for? 7 The South Wales and Severn Waterway Partnership 8 Relationships with other Partnerships 10 Our first year 11 Looking forward: our Strategic Waterway Plan 12 Vision 12 The focus of the plan 12 More information 14 More about the Trust 14 More information about our waterway area 15 SWSWP members 16 How we work as a Partnership 17 Key contacts 18 2 Chairman’s introduction It was July last year when the Canal & River Trust was established as a charitable body to care for the waterways of England and Wales, holding them in trust forever for the nation. Our Partnership is one of a number of local waterway partnerships created as an integral part of the governance of the new Trust. The local partnerships are an important outward looking component of the Trust structure as they aim to engage locally with people, decision makers and communities. As advisory partnerships, focusing on local vision and aspirations rather than operational matters, they generate great added value to the work of the trust as they develop and mature. My partnership members have been recruited from a diverse interest base and are drawn from all across the waterway area. We have spent a significant part of our formative year both collectively and individually, out and about across the region and increasing our knowledge about the work of the Trust in aspects such as such as volunteering, fundraising, heritage, development and enterprise. -

James Brindley ( 1716 - 1772 )

1 James Brindley ( 1716 - 1772 ) These notes are designed to help you with homework and other pro- jects. It will help you to find out: About James Brindley’s early life How he became a famous canal engineer His ideas and inventions. My mum taught me at home. I became the greatest canal engineer of my day! You can see this statue canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers of James Brindley at Coventry Basin 2 Mr Fixit The spokes should James Brindley was born 300 years ago point inwards, not near Buxton, in Derbyshire. As a boy he outwards, you banana! loved building toy mills and trying them out in the wind and water. Later, James was apprenticed to a master mill- and Oops! wheelwright. It didn’t start off well. He built a cartwheel with spokes facing outwards instead of inwards! Gradually, James became known as someone who could fix any machinery. When his master died he moved to Leek in Staffordshire, to start a new business there. canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers 3 The Bridgewater Canal The Bridgwater Canal was first called James’s business grew. He worked the Duke’s Canal on all kinds of machinery driven by water, wind and steam. The Duke of Worsley Bridgewater, who owned coal mines RUNCORN Barton coal fields near Manchester, heard about him. Aqueduct ell Irw R er Coal was used i iv ve y R to heat everything r M erse R R Mersey i from houses to v T he e Duk r e’s Manchester furnaces - so Can W al e everyone wanted a v cheap coal. -

Communications Update 22Nd July 2016

Communications Update 22nd July 2016 News Round Up Here's your weekly dose of waterways related media coverage · Head of museums Graham Boxer was featured on BBC Breakfast news (26/07/16) ahead of the reopening of Gloucester Waterways Museum. Graham spoke about the history of the waterways in this part of the country and the ambitions for the museum in the future · BBC Radio Leicester have taken their afternoon show out onto the River Soar. Enterprise manager James Clifton set the scene perfectly before they set off (forward 1hr 4mins) Team leader Mark Whitfield was on hand to help the team through Saddington Tunnel (2hr 47mins). You can hear the rest of their journey along Leicestershire’s waterways over the next two days at www.bbc.co.uk/radioleicester (3pm - 6pm) · BBC London and London Live (22/07/16) joined graduate ecologist and environmental scientist Chantal Dave and waterway operative Tim Mulligan to learn about the explosion of duck weed on London’s canals. The story was also reported by the Guardian (28/07/16), Daily Telegraph (24/07/16), Evening Standard (22/07/16) and local newspapers · The tragic fatality of a boater in Droitwich received a huge amount of coverage this week, with the Daily Telegraph , Mirror , Sun and ITV all reporting the incident (26/07/16). Waterway manager Nick Worthington spoke very well when interviewed by BBC Hereford & Worcester (26/07/16), among a series of interviews he did, while volunteer lock keeper James Cowlishaw was quoted by BBC Online (26/07/16) · CNN (26/07/16) is the latest outlet to -

Dundas Aqueduct Toilets

Walks on Wheels - for wheelchair, mobility scooter and children’s buggy Dundas Explore two canals. Short and ideal for all wheels plus bike and boat hire. Where is it? A46 A365 From Bath take the A36 towards Warminster. After three miles7 A4 (4.8km) and an entry sign for Limpley Stoke there are doubleB310 traffic lights. At the lights turn left down the B3108 (signed Bradford-on- Bath Avon) and quickly turn left into the Dundas Marina car park. Pay and B3109 Display. A363 A36 Dundas Bradford- The walk On-Avon B3107 B3108 This is a rural waterfront path of 400 metres along the Avon Valley B3110 to a magnificent aqueduct that carries the Kennet and Avon Canal A363 high over the river Avon and the railway. You can return the way B3108 you came (total 800 metres) or take in an interesting extension A366 alongside the largely disused Somersetshire Coal Canal, making a total 1.2 kms. The walk to the aqueduct is on gently climbing tarmac, and the canal towpaths are on level smooth grit. The route can be further extended as far as you wish in either direction along the Kennet and Avon towpath. The walk is open to all. Distance: 0.8km/1/2 mile or 1.2km/3/4 mile with used as moorings, to the visitor centre, café and ups and downs of 12m or 39ft boat/cycle hire (open all year). From here a steep zigzag path leads down to the car park, but it is Start: Dundas Marina car park by masts. -

The Economic Impact of the Restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal

The Economic Impact of the Restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal A Final Report to British Waterways ECOTEC Research & Consulting Limited Priestley House 28-34 Albert Street Birmingham B4 7UD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)121 616 3600 Fax: +44 (0)121 616 3699 Web: www.ecotec.com The Economic Impact of the Restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal A Final Report to British Waterways c2378 Ref: 16/12/2014 ECOTEC Research and Consulting Limited Priestley House 13b Avenue de Tervuren 28-34 Albert Street B-1040 Brussels Birmingham B4 7UD Belgium United Kingdom Tel: +32 (0)2 743 8949 Tel: +44 (0)121 616 3600 Fax: +32 (0)2 743 7111 Fax: +44 (0)121 616 3699 Modesto Lafuente 63 – 6a Web: www.ecotec.com E-28003 Madrid E-mail: [email protected] Spain Tel: +34 91 535 0640 Fax: +34 91 533 3663 6-8 Marshalsea Road London SE1 1HL United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7089 5550 Fax: +44 (0)20 7089 5559 31-32 Park Row Leeds LS1 5JD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)113 244 9845 Fax: +44 (0)113 244 9844 The Economic Impact of the Restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 The Kennet and Avon Canal and its Restoration .............................................................. 4 1.1.1 The History of the Kennet and Avon Canal................................................................ 4 1.1.2 The 1997 Restoration Programme .............................................................................. 5 1.2 Aims and Objectives of the Study ..................................................................................... 5 1.3 Re-visiting the 1995 Coopers and Lybrand Study ............................................................. 6 1.3.1 Methodology and Results .......................................................................................... -

Download: Pre-Submission Canalside DPD 2020

Warwick District Council CANALSIDE DRAFT DPD PRE-SUBMISSION March 2020 01 Contents 1. BACKGROUND: 26 Access 05 National and Local Policies 27 Flooding 06 Neighbourhood 28 Water Abstraction Development Plans 28 Residential Moorings 07 The Extent of this DPD 29 Marinas 07 Conservation Area 29 Future Pressures 2. CONTEXT: 5. OPTIONS 09 The Grand Union Canal, 09 The Stratford Upon Avon 31 Identifying the Potential and Birmingham and 32 Sydenham Industrial Estate Fazeley Canals 32 Cape Road/Millers Road 10 The History of Canals in 32 Montague Road Warwick District 12. How the Use of Canals 33 Recent Developments on the Has Changed Local Plan Sites 14 What Has Happened 33 Other Opportunity Sites Elsewhere? 6. POLICIES 3. THE CANAL 37 Site Specific Policies CONSERVATION AREA 7. IS THERE ANY FUTURE 4. ISSUES FOR CANALS AS FREIGHT 22 Biodiversity CORRIDORS 22 Rubbish Dumping 23 Crime and the Perception of Crime APPENDICES 23 Drug Dealing APPENDIX 1: Other Opportunity 23 Vandalism Sites Analysis 24 Aesthetics APPENDIX 2: Canalside Listed Buildings 25 HS2 APPENDIX 3: Constraints 26 Vacant and Underused Buildings 02 03 SECTION 1 BACKGROUND 04 1.1 What is a Development Plan Document (DPD)and why is one being prepared for the canals within the district? National and Local Policy Documents 1.2 The district adopted its Local Plan in Sept 2017. The Local Plan sets out the framework for future development in the district; how much, where it will be and how it will be supported in terms of infrastructure. The Plan runs from 2011 to 2029. It contains both allocations for land uses, including housing and employment, and policies by which planning applications will be assessed by development management staff and Planning Committee members. -

HARRIETT: Last of the Kennet Barges Stuart Bryan & Judith Hague Note

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1992 pages 27-33 HARRIETT: Last of the Kennet Barges Stuart Bryan & Judith Hague Note: This article was originally given as the 1992 GSIA AGM talk and was illustrated but the present illustrations are those of the editor. The article has been divided into two parts. The first is on Kennet barges and the HARRIETT. The second is on the Nautical Archaeology Society of which the authors are members and on how the survey came to be undertaken. The survey part formed a very important part of the talk but is only briefly mentioned here. Part I: The HARRIETT Introduction. London and Bristol were linked by the Thames and Severn Canal in 1794 but this link was long and unreliable. It took 9 or 10 days to travel from Brimscombe to London and 12 to 14 days to make the return journey. The opening of the Kennet and Avon Canal in 1810 created a more effective link between London and the west coast port of Bristol. The canal became an important highway in the days of poor roads, before the railways were built. It took about 7 days to travel along the canal from Bristol to London. The reverse journey took about 8 days through the inland county of Wiltshire. Honey Street In the canal side hamlet of Honey Street, between Devizes and Pewsey, the firm of Robbins‘& Co started trading in timber shortly after the opening of the canal. Soon they were making some cflf their imported timber into craft for the water. -

South Worcestershire Councils Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment

South Worcestershire Councils Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Final Report August 2019 www.jbaconsulting.com South Worcestershire Councils This page is intentionally left blank 2018s1367 - South Worcestershire Councils - Level 1 SFRA Final Report v1.0.docx ii JBA Project Manager Joanne Chillingworth The Library St Philips Courtyard Church Hill Coleshill Warwickshire B46 3AD Revision history Revision Ref/Date Amendments Issued to Draft Report v1.0/ Draft Report Angie Matthews December 2018 (Senior Planning Officer) Draft Report v2.0/May Addition of cumulative impact Angie Matthews 2019 assessment, updated report layout (Senior Planning Officer) Final Report v1.0/August Addressed stakeholder comments Angie Matthews 2019 (Senior Planning Officer) Contract This report describes work commissioned by the South Worcestershire Councils (Wychavon District Council, Malvern Hills District Council and Worcester City Council), by an email dated 12th October 2018 from Wychavon District Council. Lucy Finch of JBA Consulting carried out this work. Prepared by .................................. Lucy Finch BSc Analyst Reviewed by .................................. Joanne Chillingworth BSc MSc MCIWEM C.WEM Principal Analyst Hannah Coogan BSc MCIWEM C.WEM Technical Director Purpose This document has been prepared as a Final Report for the South Worcestershire Councils (Malvern Hills District Council, Wychavon District Council and Worcester City Council). JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document -

Sj\-U<Dss Q\J(Dih

sj\-u<dss Q\j(dih Box 3, ENVIRONMENT AGENCY BLUE-GREEN ALGAL MONITORING 1998 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR ECOTOXICOLOGY & HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES NUTRIENTS SECTION Final Report November, 1999 \ \ J I ( .1 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 122766 CONTENTS SUMMARY..........................................................................................................................2 1. INTRODUCTION........................................ ..................................................................4 1.1 Action by the Environment Agency in response to cyanobacterial blooms and scums.................................................................................................................................4 1.2 Purpose of this report................................................................................................. 6 2. CYANOBACTERIAL MONITORING.........................................................................6 2.1 Waterbodies sampled reactively for the first time..................................................... 6 2.2 Waterbodies sampled reactively in the past which were subsequently re-sampled.. 7 2.3 Annual fluctuations...........................................>......................................................... 8 2.4 Waterbodies sampled routinely......................................................... ........................ 9 2.5 Long-term monitoring...............................................................................................11 2.6 Visual inspections.................................................................................................... -

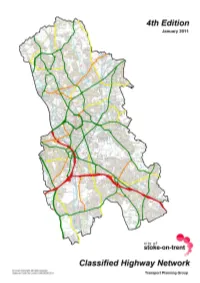

Classified Highway Network Document 4.00 Jan11

City of Stoke-on-Trent Classified Highway Network January 2011 Version 4.00 INTRODUCTION This document supersedes Version 3.01, May 2008. The information within this document describes the Classified Highway Network as of January 2011. The document illustrates and lists all classified roads within Stoke-on-Trent including all A (trunk and principal), B and C roads. It also defines the Strategic Highway and Primary Route Networks. For enquiries or further information please contact: Transport Planning Group City Renewal Stoke-on-Trent City Council PO Box 630 Civic Centre Glebe Street Stoke-on-Trent ST4 1RF T: 01782 232149 E: [email protected] - 1 - City of Stoke-on-Trent Classified Highway Network January 2011 Version 4.00 - 2 - City of Stoke-on-Trent Classified Highway Network January 2011 Version 4.00 SCHEDULE OF CLASSIFIED ROADS Principal Roads – Sorted by Number Road Number Name Road Number Name A34 NEWCASTLE ROAD A5035 TRENTHAM ROAD A34 STONE ROAD A52 BUCKNALL ROAD A50 HIGH STREET A52 CAMPBELL PLACE A50 HIGH STREET (SANDYFORD) A52 CHURCH STREET A50 KIDSGROVE ROAD A52 CITY ROAD A50 KING STREET A52 COPELAND STREET A50 LICHFIELD STREET A52 ELENORA STREET A50 POTTERIES WAY A52 FLEMING ROAD A50 SCOTIA ROAD A52 GLEBE STREET A50 SWAN SQUARE A52 HARTSHILL ROAD A50 VALE PLACE A52 LEEK ROAD A50 VICTORIA PLACE A52 LIVERPOOL ROAD A50 A50 (VICTORIA PLACE LINK) A52 LONDON ROAD A50 VICTORIA ROAD A52 LONSDALE STREET A50 WATERLOO ROAD A52 SHELTON OLD ROAD A50 WEDGWOOD PLACE A52 WERRINGTON ROAD A50 WEDGWOOD STREET A52 WOODHOUSE STREET A50(T)