Human Streets, the Mayor's Vision for Cycling, Three Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater London Authority

Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London March 2009 Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London A report by Experian for the Greater London Authority March 2009 copyright Greater London Authority March 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 227 8 This publication is printed on recycled paper Experian - Business Strategies Cardinal Place 6th Floor 80 Victoria Street London SW1E 5JL T: +44 (0) 207 746 8255 F: +44 (0) 207 746 8277 This project was funded by the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. The views expressed in this report are those of Experian Business Strategies and do not necessarily represent those of the Greater London Authority or the London Development Agency. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................... 5 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 5 CONSUMER EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS .................................................................................... 6 CURRENT COMPARISON FLOORSPACE PROVISION ....................................................................... 9 RETAIL CENTRE TURNOVER........................................................................................................ 9 COMPARISON GOODS FLOORSPACE REQUIREMENTS -

(Public Pack)Cycle Superhighway Supplement Agenda Supplement

Public Document Pack Planning and Transportation Committee Date: TUESDAY, 24 FEBRUARY 2015 Time: 11.00 am Venue: LIVERY HALL - GUILDHALL ITEM 10 CYCLE SUPERHIGHWAYS - APPENDIX John Barradell Town Clerk and Chief Executive This page is intentionally left blank Board Date: 4 February 2015 Item 7: Proposed Cycle Superhighways Schemes This paper will be considered in public 1 Summary 1.1 TfL’s Road Modernisation Plan is designed to get more from the road network and help London grow. It contains five core portfolios, which together make up the £4bn roads investment in Surface Transport’s ten year business plan. The Cycle Superhighways (CS) programme is a key element within the £0.9bn cycling portfolio to deliver the ‘Mayor’s Vision for Cycling in London’, which seeks to double cycling over the next 10 years and transform London’s streets and spaces to places where cyclists feel they belong and are safe. £0.2bn from the cycling budget has been committed to the CS programme, to provide TfL with the resources to deliver significant improvements, including the proposed East-West route. 1.2 The CS programme is essential for improving the levels of service experienced by the hundreds of thousands of people already cycling daily in London, as well as driving future demand for cycling. The proposed routes deliver the backbone for the wider cycling infrastructure proposals, linking Quietways and existing London Cycle Network (LCN) routes to key home and workplace destinations, providing attractive high-capacity routes for commuters and leisure users alike. 1.3 This paper seeks Board approval for the construction of four new Cycle Superhighways (CS), and upgrades to the four existing CS routes. -

FOR SALE 331 KENNINGTON LANE, VAUXHALL, SE11 5QY the Location

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY CONSULTANT S 9 HOLYROOD STREET, LONDON, SE1 2EL T: 0207 939 9550 F: 0207 378 8773 [email protected] WWW.ALEXMARTIN.CO.UK PROPERTY PARTICULARS FOR SALE 331 KENNINGTON LANE, VAUXHALL, SE11 5QY The Location The property is situated in Kennington on the southern side of Kennington Lane (A3204) adjacent to the Lilian Baylis Technology School. The roperty is a short distance from Vauxhall Tube and British Rail Stations and also Vauxhall Bridge and the River Thames. The immediate environs are mixed use with educational, residential and retail. The open space of Spring Gardens, Vauxhall Farm, Vauxhall Park, Kennington Park and The Oval (Surrey County Cricket Club) are nearby. The property is located within the Vauxhall Conservation Area. FREEHOLD AVAILABLE (UNCONDITIONAL/ CONDITIONAL OFFERS INVITED) Description The property comprises a substantial mainly detached four storey and basement Victorian building last used for educational purposes by Five Bridges, a small independent school catering for 36 pupils. There are two parking spaces at the front, side pedestrian access and mainly paved rear yard with a substantial tree. The property is of typical construction for its age with solid built walls, pitched slate roofs, double hung single glazed sliding sash windows and timber suspended floors. The property benefits from central heating. COMMERCIAL PROPERTY CONSULTANT S 9 HOLYROOD STREET, LONDON, SE1 2EL T: 0207 939 9550 F: 0207 378 8773 [email protected] WWW.ALEXMARTIN.CO.UK PROPERTY PARTICULARS The accommodation comprises a net internal area of approximately: Floor Sq m Sq ft Basement 95 1,018 Ground 110 1,188 First 102 1,101 Second 100 1,074 Third 109 1,171 Total 516 5,552 The total gross internal area is 770 sq m (8,288 sq ft) The property is offered for sale freehold with vacant possession and offers are invited ‘Subject to Contract’ either on an ‘unconditional’ or ‘subject to planning’ basis General The property is located within Vauxhall Conservation Area (CA 32) and a flood zone as identified on the proposals map. -

192-198 Vauxhall Bridge Road , London Sw1v 1Dx

192-198 VAUXHALL BRIDGE ROAD , LONDON SW1V 1DX OFFICE TO RENT | 2,725 SQ FT | £45 PER SQ FT. VICTORIA'S EXPERT PROPERTY ADVISORS TUCKERMAN TUCKERMAN.CO.UK 1 CASTLE LANE, VICTORIA, LONDON SW1E 6DR T (0) 20 7222 5511 192-198 VAUXHALL BRIDGE ROAD , LONDON SW1V 1DX REFURBISHED OFFICE TO RENT DESCRIPTION AMENITIES The premises are located on the east side of Vauxhall Bridge Road, Comfort cooling between its junctions with Rochester Row and Francis Street. Excellent natural light Secondary glazing The area is well served by transport facilities with Victoria Mainline Perimeter trunking and Underground Stations (Victoria, Circle and District lines) being approximately 400 yards to the north. Suspended ceilings Fibre provision up to 100Mbs download & upload including There are excellent retail and restaurant facilitates in the secondary fallover connection surrounding area, particularly within Nova, Cardinal Place on Capped off services for kitchenette Victoria Street and also within the neighbouring streets of Belgravia. Lift Car parking (by separate arrangement) The plug and play accommodation is arranged over the third floor and is offered in an open plan refurbished condition. TERMS *Refurbished 1st floor shown, 3rd floor due to be refurbished. RENT RATES S/C Please follow this link to see a virtual walk through; £45 per sq ft. £16.92 per sq ft. £6.34 per sq ft. https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=MZvVtMCSkkz Flexible terms available. AVAILABILITY EPC Available upon request. FLOOR SIZE (SQ FT) AVAILABILITY WEBSITE Third Floor 2,725 Available http://www.tuckerman.co.uk/properties/active/192-198-vauxhall- TOTAL 2,725 bridge-road/ GET IN TOUCH WILLIAM DICKSON HARRIET DE FREITAS Tuckerman Tuckerman 020 3328 5374 020 3328 5380 [email protected] [email protected] SUBJECT TO CONTRACT. -

Tfl Strategic Cycling Analysis Report

Strategic Cycling Analysis Identifying future cycling demand in London June 2017 Contents Page Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 PART ONE Chapter 1: The Strategic Cycling Analysis 8 Chapter 2: Cycling Connections 15 PART TWO Chapter 3: Healthy Streets benefits of the Strategic Cycling Analysis 25 Chapter 4: Area-wide opportunities to expand Cycling Connections 43 PART THREE Chapter 5: Conclusions and next steps 49 Executive Summary The Strategic Cycling Analysis The Mayor has asked Transport for London to put the The report considers four broad areas of analysis: Healthy Streets Approach at the heart of its decision making. Where are the cycling connections with the greatest Set out in ‘Healthy Streets for London’, this approach is a potential to contribute to cycling growth in London? system of policies and strategies to help Londoners use cars less and walk, cycle and use public transport more often. How could these connections be prioritised? How could these connections contribute towards To achieve this it is important to plan a longer-term and achieving Healthy Streets goals? coherent cycle network across London in a way that will What opportunities are there to deliver area-wide complement walking and public transport priorities. This cycling improvements? document provides a robust, analytical framework to help do this. Each chapter addresses one of these questions, describing the datasets, methodology and findings together with next The Strategic Cycling Analysis presents what the latest steps. datasets, forecasts and models show about potential corridors and locations where current and future cycling Next steps demand could justify future investment. It also identifies The Strategic Cycling Analysis identifies a number of where demand for cycling, walking and public transport schematic cycling connections which could contribute to the coincide, thus highlighting where investment is most needed growth of cycling in London and help achieve the Mayor’s to improve all sustainable transport modes together. -

Benefits of Investing in Cycling

BENEFITS OF INVESTING IN CYCLING Dr Rachel Aldred In association with 3 Executive summary Investing in cycling; in numbers Dr. Rachel Aldred, Senior Lecturer in Transport, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, University of Westminster Danish levels of cycling in the UK would save the NHS billion ... and increase mobility of the £17within 20 years nation’s poorest families by 25% Cycling saves a third of road space More cycling and other compared to driving, to help sustainable transport could cut congestion reduce road deaths by 30% Investing in cycling will generate benefits for the whole country, not just those using a bike to get around. Eleven benefits are summarised here which can help solve a series of health, social and economic problems. This report shows how investing in cycling is good for our transport systems as a whole, for local economies, for social Bike parking takes up inclusion, and for public health. 8 times less space than Bike lanes Creating a cycling revolution in the UK requires cars, helping to free up space can sustained investment. In European countries with high cycling levels, levels of investment are also increase substantially higher than in the UK. The All-Party retail sales Parliamentary Cycling Inquiry has recommended by a quarter a minimum of £10 annually per person, rising to £20, which would begin to approach the spending levels seen in high-cycling countries. Shifting just 10% of journeys Investing in cycling will enable transport authorities from car to bike would reduce to start putting in place the infrastructure we need air pollution and save Adopting Dutch to ensure people of all ages and abilities can 400 productive life years safety standards choose to cycle for short everyday trips. -

369 Kennington Lane, Vauxhall, SE11 5QY OFFICE to LET | HEART of VAUXHALL | READY for OCCUPATION to LET Area: 831 FT² (77M²) | Initial Rent: £38,000 PA |

369 Kennington Lane, Vauxhall, SE11 5QY OFFICE TO LET | HEART OF VAUXHALL | READY FOR OCCUPATION TO LET Area: 831 FT² (77M²) | Initial Rent: £38,000 PA | Location Tube Parking Availability Vauxhall Vauxhall 2 spaces available Immediate LOCATION: Situated just south of Central London, 369 Kennington Lane is a highly prominent office building positioned at the junction of Kennington Lane and Harleyford Road. Excellent transport connections via Vauxhall Station (Mainline and Victoria Line) providing easy and direct links into Central London. The area is similarly well connected to local bus routes. The A3 Kennington Park Road is easily accessed to the South East and to the West, Vauxhall Bridge provides access north of the River Thames, through to Victoria and to the West End. The popular residential and commercial area offers a wide range of cafés, bars and restaurants including; Pret A Manger, Starbucks Coffee, Dirty Burger along with a number of local independent retailers. Cont’d MISREPRESENTATION ACT, 1967. Houston Lawrence for themselves and for the Lessors, Vendors or Assignors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: These particulars do not form any part of any offer or contract: the statements contained therein are issued without responsibility on the part of the firm or their clients and therefore are not to be relied upon as statements or representations of fact: any intending tenant or purchaser must satisfy himself as to the correctness of each of the statements made herein: and the vendor, lessor or assignor does not make or give, and neither the firm or any of their employees have any authority to make or give, any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. -

Kings Cross to Liverpool Street Via 13 Stations Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Kings Cross to Liverpool Street via 13 stations walk All London’s railway terminals, the three royal parks, the River Thames and the City Length 21.3km (13.3 miles) for the whole walk, but it is easily split into smaller sections: see Walk Options below Toughness 1 out of 10 - entirely flat, but entirely on hard surfaces: definitely a walk to wear cushioned trainers and not boots. Features This walk links (and in many cases passes through) all thirteen London railway terminals, and tells you something of their history along the way. But its attractions are not just limited to railway architecture. It also passes through the three main Central London parks - Regent’s Park, Hyde Park/Kensington Gardens and St James's Parks - and along the Thames into and through the City of London*. It takes in a surprising number of famous sights and a number of characteristic residential and business areas: in fact, if you are first time visitor to London, it is as good an introduction as any to what the city has to offer. Despite being a city centre walk, it spends very little of its time on busy roads, and has many idyllic spots in which to sit or take refreshment. In the summer months you can even have an open air swim midway through the walk in Hyde Park's Serpentine Lido. (* The oldest part of London, now the financial district. Whenever the City, with a capital letter, is used in this document, it has this meaning.) Walk Being in Central London, you can of course start or finish the walk wherever Options you like, especially at the main railway stations that are its principal feature. -

Thames Path Walk Section 2 North Bank Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge

Thames Path Walk With the Thames on the right, set off along the Chelsea Embankment past Section 2 north bank the plaque to Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also created the Victoria and Albert Embankments. His plan reclaimed land from the Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge river to accommodate a new road with sewers beneath - until then, sewage had drained straight into the Thames and disease was rife in the city. Carry on past the junction with Royal Hospital Road, to peek into the walled garden of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Version 1 : March 2011 The Chelsea Physic Garden was founded by the Worshipful Society of Start: Albert Bridge (TQ274776) Apothecaries in 1673 to promote the study of botany in relation to medicine, Station: Clippers from Cadogan Pier or bus known at the time as the "psychic" or healing arts. As the second-oldest stops along Chelsea Embankment botanic garden in England, it still fulfils its traditional function of scientific research and plant conservation and undertakes ‘to educate and inform’. Finish: Tower Bridge (TQ336801) Station: Clippers (St Katharine’s Pier), many bus stops, or Tower Hill or Tower Gateway tube Carry on along the embankment passed gracious riverside dwellings that line the route to reach Sir Christopher Wren’s magnificent Royal Hospital Distance: 6 miles (9.5 km) Chelsea with its famous Chelsea Pensioners in their red uniforms. Introduction: Discover central London’s most famous sights along this stretch of the River Thames. The Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s The Royal Hospital Chelsea was founded in 1682 by King Charles II for the Cathedral, Tate Modern and the Tower of London, the Thames Path links 'succour and relief of veterans broken by age and war'. -

Westminsterresearch Diversifying and Normalising Cycling in London

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Diversifying and normalising cycling in London, UK: An exploratory study on the influence of infrastructure Aldred, R. and Dales, J. NOTICE: this is the authors’ version of a work that was accepted for publication in Journal of Transport and Health. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive version was subsequently published in Journal of Transport and Health, doi:10.1016/j.jth.2016.11.002, 2016. The final definitive version in Journal of Transport and Health is available online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2016.11.002 © 2016. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Author version of paper; published in Journal of Transport and -

Victoria Embankment Foreshore Hoarding Commission

Victoria Embankment Foreshore Hoarding Commission 1 Introduction ‘The Thames Wunderkammer: Tales from Victoria Embankment in Two Parts’, 2017, by Simon Roberts, commissioned by Tideway This is a temporary commission located on the Thames Tideway Tunnel construction site hoardings at Victoria Embankment, 2017-19. Responding to the rich heritage of the Victoria Embankment, Simon Roberts has created a metaphorical ‘cabinet of curiosities’ along two 25- metre foreshore hoardings. Roberts describes his approach as an ‘aesthetic excavation of the area’, creating an artwork that reflects the literal and metaphorical layering of the landscape, in which objects from the past and present are juxtaposed to evoke new meanings. Monumental statues are placed alongside items that are more ordinary; diverse elements, both man-made and natural, co-exist in new ways. All these components symbolise the landscape’s complex history, culture, geology, and development. Credits Artist: Simon Roberts Images: details from ‘The Thames Wunderkammer: Tales from Victoria Embankment in Two Parts’ © Simon Roberts, 2017. Archival images: © Copyright Museum of London; Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum; Wellcome Library, London; © Imperial War Museums (COM 548); Courtesy the Parliamentary Archives, London. Special thanks due to Luke Brown, Demian Gozzelino (Simon Roberts Studio); staff at the Museum of London, British Museum, Houses of Parliament, Parliamentary Archives, Parliamentary Art Collection, Wellcome Trust, and Thames21; and Flowers Gallery London. 1 About the Artist Simon Roberts (b.1974) is a British photographic artist whose work deals with our relationship to landscape and notions of identity and belonging. He predominantly takes large format photographs with great technical precision, frequently from elevated positions. -

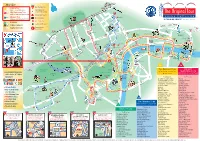

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk