The Conflict Between Mobilizing Hunger Strikes and Distracting Media Frames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Letter to Children of Bal Mandir

1. LETTER TO CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR KARACHI, February 4, 1929 CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR, The children of the Bal Mandir1are too mischievous. What kind of mischief was this that led to Hari breaking his arm? Shouldn’t there be some limit to playing pranks? Let each child give his or her reply. QUESTION TWO: Does any child still eat spices? Will those who eat them stop doing so? Those of you who have given up spices, do you feel tempted to eat them? If so, why do you feel that way? QUESTION THREE: Does any of you now make noise in the class or the kitchen? Remember that all of you have promised me that you will make no noise. In Karachi it is not so cold as they tried to frighten me by saying it would be. I am writing this letter at 4 o’clock. The post is cleared early. Reading by mistake four instead of three, I got up at three. I didn’t then feel inclined to sleep for one hour. As a result, I had one hour more for writing letters to the Udyoga Mandir2. How nice ! Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 9222 1 An infant school in the Sabarmati Ashram 2 Since the new constitution published on June 14, 1928 the Ashram was renamed Udyoga Mandir. VOL.45: 4 FEBRUARY, 1929 - 11 MAY, 1929 1 2. LETTER TO ASHRAM WOMEN KARACHI, February 4, 1929 SISTERS, I hope your classes are working regularly. I believe that no better arrangements could have been made than what has come about without any special planning. -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

History & Industry of Mass Communication

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping History & Industry of Mass Communication Study Material for Students 1 1111111 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping History & Industry of Mass Communication CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman, producer, director, etc. Other titles of Mass Communication professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping History & Industry of Mass Communication INTRODUCTION This book comprise of five units. First unit of this book explains the meaning and significance of mass communication. The unit will explain the importance mass communication by tracing the history of Mass Communication through different Eras. This unit also introduces you to the stages in the Development of Advertising. -

UNIVERSITY of DELHI Faculty of Law MASTER of LAWS (2Year/3 Year) LL.M

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI Faculty of Law MASTER OF LAWS (2Year/3 Year) LL.M. (2 Year/3 Year) Semester II/ Semester IV Course Code: 2YLM-EC-211/3YLM-EC-211 Law, Media and Censorship Prepared and Compiled by Dr. Namita Vashishtha Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Pr ess Laws & Media Ethics SEMESTER 4 Study Material for Students Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Press Laws & Media Ethics CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman, producer, director, etc. Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 | Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Press Laws & Media Ethics INTRODUCTION This book is related to the basic knowledge of media laws and press code of conduct. -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 017 908 48 AL 000 990 CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION--A HANDBOOK OF READINGS TO ACCOMPANY THE CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS. VOLUME II, BRITISH AND MODERN INDIA. BY- ELDER, JOSEPH W., ED. WISCONSIN UNIV., MADISON, DEPT. OF INDIAN STUDIES REPORT NUMBER BR-6-2512 PUB DATE JUN 67 CONTRACT OEC-3-6-062512-1744 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.25 HC-$12.04 299P. DESCRIPTORS- *INDIANS, *CULTURE, *AREA STUDIES, MASS MEDIA, *LANGUAGE AND AREA CENTERS, LITERATURE, LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION, INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, DRAMA, MUSIC, SOCIOCULTURAL PATTERNS, INDIA, THIS VOLUME IS THE COMPANION TO "VOLUME II CLASSICAL AND MEDIEVAL INDIA," AND IS DESIGNED TO ACCOMPANY COURSES DEALING WITH INDIA, PARTICULARLY THOSE COURSES USING THE "CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS"(BY THE SAME AUTHOR AND PUBLISHERS, 1965). VOLUME II CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING SELECTIONS--(/) "INDIA AND WESTERN INTELLECTUALS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER,(2) "DEVELOPMENT AND REACH OF MASS MEDIA," BY K.E. EAPEN, (3) "DANCE, DANCE-DRAMA, AND MUSIC," BY CLIFF R. JONES AND ROBERT E. BROWN,(4) "MODERN INDIAN LITERATURE," BY M.G. KRISHNAMURTHI, (5) "LANGUAGE IDENTITY--AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIA'S LANGUAGE PROBLEMS," BY WILLIAM C. MCCORMACK, (6) "THE STUDY OF CIVILIZATIONS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER, AND(7) "THE PEOPLES OF INDIA," BY ROBERT J. AND BEATRICE D. MILLER. THESE MATERIALS ARE WRITTEN IN ENGLISH AND ARE PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON, WISCONSIN 53706. (AMM) 11116ro., F Bk.--. G 2S12 Ye- CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION JOSEPH W ELDER Editor VOLUME I I BRITISH AND MODERN PERIOD U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Goa Political Conference

Goa Political Conference Under the auspices of the Goa Congress Committee a meeting was held on Sunday the 24th instant at 10 a.m. in the Maharashtra School, Opera House. The meeting was held to discuss certain arrangements to be made in connection with the proposed Goa Political Conference to be held in Bombay next month. The meeting was open only to members of the Goa Congress Committee and was a private meeting. 50 I was present outside till the meeting got over at about 11-30 a.m. and gathered the following information in a discreet manner :— That Dr. A. G. Tendulkar presided over the meeting and that a reception committee of about 10 persons (all Goans) was formed to settle the place of the conference, to invite certain delegates and to make arrangement, for their stay in Bombay. The co-operation of all Nationalist News papers was requested to give publicity about the forthcoming conference and in particular the Konkani papers of Bombay were requested to send their representatives so that the news may reach in Goa. It was also decided to hold a further meeting within the next fortnight to decide upon other matters such as selection of a President of the Conference etc., about 15 persons attending the meeting. F. J. D'SOUZA, S. B. (I)., 25th March 1946. The Bharat Jyoti, dated 14th April 1946. Goa Staunchly behind United India The President of the Goa Congress Committee, Dr. A. G. Tendulkar has sent a telegram to the President of the Indian National Congress, Pandit Jawaharalal Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel stating that the Goa Congress Committee adheres to the principle of territorial integrity of India and requests Congress recognition in the forthcoming constitution of the right of the people of Goa, Daman and Diu for self-determination and their desire for re-union with the mother country. -

Palak Sharma

A PROJECT REPORT ON WHAT PEOPLE WANT IN THEIR NEWSPAPER SUBMITTED TO EMPI B-SCHOOL, NEW DELHI IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME OF RESEARCH & BUSINESS ANALYTICS 2008-2010 SUBMITTED BY PALAK SHARMA SUBMITTED TO MR. DAVID EASOW DIRECTOR, VC-MAGTICS INDEX SR. NO TITLE PAGE NO 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 03 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 04 3 SCOPE OF THE STUDY 05 4 OBJECTIVE OF SURVEY 06 5 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 07 6 INTRODUCTION 09 7 GRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF THE 37 QUESTIONNAIRE 8 FINDING 49 9 BIBLIOGRAPHY 50 10 QUESTIONNAIRE 11 SPREADSHEET ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 2 BEFORE I GO ON TO ELABORATE AND EXPLAIN THIS EXHAUSTIVE PIECE OF WORK, I WOULD FIRST AND FOREMOST LIKE TO EXPRESS MY HEARTFELT GRATITUDE TO A FEW PEOPLE WHO HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO THE SUCCESSFUL COMPLETION OF MY THESIS. HEADING THE LIST IS MY GUIDE MR. SANDEEP SHARMA AND OTHER PEOPLE IN MARKETING DEPARTMENT, MY EDUCATIONAL GUIDE MR. NISHIKANT BELE AND MY HOD MR. DAVID EASOW WITHOUT WHOSE INVALUABLE SUPPORT AND CONSTANT GUIDANCE THIS THESIS WOULD NOT HAVE SEEN THE LIGHT OF DAY. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY THE COMPILED REPORT SIGNIFIES THE STUDY WHICH HAS BEEN ON TOPIC ³ WHAT PEOPLE WANT IN THEIR NEWSPAPER´.THIS SURVY IS DONE UNDER DANIK BHASKAR .THE SAMPLE SIZE TAKEN IS 100. AND ALL RESPONDENT WERE DIVIDED IN DIFFERENT SEGMENTS ON THE BASIS OF THEIR OCCUPATIONS.THEREFORE 20 STUDENTS , 20 WORKING WOMEN, 20 WORKING MEN,AND 20 RETIRED PEOPLE WERE CONSIDED.THE WHOLE SURVEY WAS DONE IN 2 MONTHS . THE WHOLE DATA IS INTERPRETED AND ANALYSED ON MICROSOFT EXCEL. -

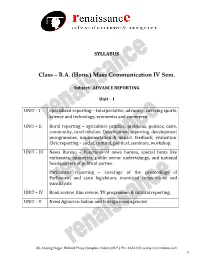

Class – B.A. (Hons.) Mass Communication IV Sem

SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (Hons.) Mass Communication IV Sem. Subject: ADVANCE REPORTING Unit – I UNIT – I Specialized reporting: - Interpretative, advocacy, covering sports, science and technology, economics and commerce. UNIT – II Rural reporting – agriculture practice, problems, policies, caste, community, rural relation. Development reporting, development porogrammes, implementation & impact, feedback, evaluation. Civic reporting – social, cultural, political, seminars, workshop. UNIT – III News Bureau – Functions of news bureau, special beats like embassies, ministries, public sector undertakings, and national headquarters of political parties. Parliament reporting – Coverage of the proceedings of Parliament and state legislature, municipal corporations and panchayats UNIT – IV Book review, film review, TV programme & cultural reporting. UNIT – V News Agencies: Indian and Foreign news agencies 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 Class – B.A. (Hons.) Mass Communication IV Sem. Subject: Advance Reporting Unit – I Interpretative reporting Interpretative reporting, as the phrase suggests, combines facts with interpretation. It delves into reasons and meanings of a development. It is the interpretative reporter’s task to give the information along with an interpretation of its significance. In doing so he uses his knowledge and experience to give the reader an idea of the background of an event and explain the consequences it could led to. Besides his own knowledge and research in the subject, he often has to rely on the opinions of specialists to-do a good job. In the USA, the first important inputs to interpretative reporting was provided by World-War-I. Curtis D. MacDongall writes in his book Interpretation reporting that when the First world War broke out, most Americans were taken by surprise. -

The Story of the Indian Press Reba Chaudburi

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY March 12, 1955 The Story of the Indian Press Reba Chaudburi (Continued from page 292 of issue dated February 26, 1955) BOUT this time two domi social and administrative evils and dealt with printing presses and news A nating personalities appeared critically examined the British policy papers and later came to be known on the scene—James Silk Bucking both in India and Ireland. With as ' The Press and Registration of ham and Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the extinction of Calcutta Journal, Books Act '. After this it was —who were destined to play a sig the John Bull and Hurkara took up amended by Act X of 1890 and by nificant part in the fight for the free the controversy of the freedom of Acts III and X of 1914 and it was dom of the Press. Both attracted the Press. further modified in 1952 and 1953. staunchest supporters from among VERNACULAR PRESS ACT their countrymen and at the same LORD BENTINCK'S ENCOURAGEMENT time provoked the bitterest anta Meanwhile, Government was be John Adam's regulations were the gonisms. Buckingham edited his coming increasingly uneasy about the fore-runner of the Vernacular Press paper, Calcutta Journal, fearlessly attitude of the Press generally and Act of 1878 which both in concep till 1823 when he was deported. its relation with Government. It tion and its application drew a clear Raja Ram Mohan's incursion into was particularly apprehensive of the distinction between the two sections Indian language press as preparations journalism was only to propagate of the Press. -

Series Roll No

QUESTION BOOKLET A Sr. No. Series Roll No. (in Figures) : _________________________________________________ Roll No. (in Words) : _________________________________________________ : 2 : 85 Time : 2 Hours Screening Test Maximum Marks : 85 PLEASE READ THIS PAGE CAREFULLY. Note : Candidate should remove the sticker seal and open this Booklet ONLY after announcement by centre superintendent and should thereafter check and ensure that this Booklet contains all the 24 pages and 24 tally with the same Code No. given at top of first page & the bottom of each & every page. If you find any defect, variation, torn or unprinted page, please have it replaced at once before you start answering. 1. IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS : 1. The Answer sheet of a candidate who does not write his Roll No., or writes an incorrect Roll No. on the title page of the Booklet and in the space provided on the Answer sheet will neither be 2. 170 evaluated nor his result declared. 3. 2. The paper contains 170 questions. 3. Attempt all questions as there will be no Negative 4. Marking. 4. The questions are of objective type. Here is an example. Question : 8 Taj Mahal was built by_____ (A) Sher Shah (B) Aurangzeb (C) Akbar (D) Shah Jahan The correct answer of this question is Shah Jahan. You will therefore darken the circle with ink pen below column (D) as shown below : A B C D A B C D Q.8 Q.8 5. 5. Each question has only one correct answer. If you give more than one answer, it will be considered wrong and it will not be evaluated. -

THE COLLECTED WORKS of MAHATMA GANDHI Right Course? Nor Can One Deny His Downright Honesty

1. NOTES INDIANS IN FIJI1 A cablegram from Suva says, “Indian members motion common franchise rejected Council today all three resigned”. This means that the Fijian Legislative Council would not have Indians on a common franchise. That would be too much for the white exploiters of Indian labour. The Indian members elected by Indian electors only have really no influence in the Legislative Council. I congratulate the three members on their patriotic spirit in having resigned from the Council by way of protest. I hope that they will on no account reconsider their decision unless a common franchise is obtained. Having resigned however they must not sit idle but continue their agitation for the simple justice to which they are entitled. If the Indian colony in Fiji is well organized, the citadel of anti-Indian prejudice is bound to break down through united effort. IS IT A SALE OF INDULGENCES ? A student writes from Lucknow as follows:2 I should be sorry to discover that the students and others who pay to the khadi fund do so not with the intention of using khadi themselves but merely as a salve for their conscience. I have warned audiences paying their subscriptions that their payment of subscri- ption is an earnest of their desire to wear khadi as far as they can. The writer of the letter seems to think that khaddarites do not subscribe. The fact however is that those who wear khadi are the largest single subscribers. If people merely paid subscriptions to the khadi fund and none used khadi, the subscriptions would be perfectly useless, for they are not given as donations to the poor but as a return for work done, and if the fruits of their work are not used by the people, their work becomes useless. -

Propaganda and the Press in the Indian Nationalist Struggle, 1920–1947 Milton Israel Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-42037-2 - Communications and Power: Propaganda and the Press in the Indian Nationalist Struggle, 1920–1947 Milton Israel Index More information Index Abhyankar, M. V. 162 Atlantic Monthly 296 Adam Regulations 3-4, 16 Australian Cable Service 141 Advance 174 Azad, Abul Kalam 167 Advocate of India 132-3, 235 African Comrade 171 Bajaj, Jamnalal 223 Agra Citizen 186 Bajpai, R. S. 47, 59, 102, 261, 287 Aiyar, G. H. Vasudeva 47 Bajpai, Ramlal 300, 302-3 Akali 183 Baldwin, Roger 279, 300-1 Akali Movement 179, 180-2, 200, 201 Baltimore Sun 308 Alexander, Horace 264 Bande Mataram 132 Aligarh Mail 66 Bande Matatam (Geneva) 247, 256 Ali, Mohammed 8 Banerjee, S. N. 171, 189, 194, 197, 220 Allahabad Law Journal Press 166 Banker, Shankerlal 231 Allen, C. T. 211 Bardoli Programme 159, 229 All-India Trade Union Congress 261 Barns, Mary 154 All-Parties Conference 72, 171, 173, 263 Basumati 44, 90, 169, 174, 214 All-Parties Fund 171 Belgaumwalla, N. H. 203—4, 231, 234, 237-8 Aman Sabha 41-3, 74 Bengal Gazette 2 Ambedkar, B. R. 175 Bengalee 5, 23, 132, 171-2, 197 Amery, L. S. 313-14 Bengal National Chamber of Commerce American Commission to Promote 148 Self-Government in India 285 Besant, Annie 195, 214, 246, 248-9, 271, Amrita Bazar Patrika 5, 8, 17, 23, 44-5, 60, 277 62-3, 89-90, 94-5, 113, 152, 169, 172, Bhopal, Nawab of 201, 203, 276 174, 176, 195, 197,209,217 Birla, G. D. 36, 94, 130-1, 135, 138-40, Amritsar Massacre 10-11, 18, 54, 127, 169, 144, 148-9, 165, 175, 199-200, 224 222, 228, 249 Blackett, Sir Basil 39 Andhra Patrika 134 Boehm, Sir Edgar 26-7 Andrews, C.