Print 01/03 January 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking in the Isles of Scilly

WALKING IN THE ISLES OF SCILLY 11 WALKS AND 4 BOAT TRIPS EXPLORING THE BEST OF THE ISLANDS by Paddy Dillon JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Paddy Dillon 2021 CONTENTS Fifth edition 2021 ISBN 978 1 78631 104 7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................5 Location ..........................................................6 Fourth edition 2015 Geology ..........................................................6 Third edition 2009 Ancient history .....................................................7 Second edition 2006 Later history .......................................................9 First edition 2000 Recent history .....................................................10 Getting to the Isles of Scilly ..........................................11 Getting around the Isles of Scilly ......................................13 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper on behalf of Latitude Press. Boat trips ........................................................15 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Tourist information and accommodation ................................15 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Maps of the Isles of Scilly ............................................17 The walks ........................................................18 Guided walks .....................................................19 Island flowers .....................................................20 © Crown copyright -

The Psychology of Ego-Involvements Latitude and for Each Degree of Hour-Angle, the Social Attitudes and Identifications

No. 4105 July 3, 1948 NATURE 7 Astronomical Navigation Tables America, about 140 to the whole of Eurasia, 38 to (Air Publication 1618.) Vol. A: Latitudes 0°-4° Africa. and 30 to Australasia. and Antarctica. The North and South. Prepared by H.M. Nautical aim is to say something about every region and Almanac Office on behalf of the Air Ministry. Pp. every country and every really big town, and to 233. (London: H.M. Stationery Office, n.d.) 7s. 6d. follow as uniform a. plan as possible, all commendable net. in a certain measure as facilitating reference to a N 1936 the Nautical Almanac Office undertook, by limited extent ; but the book needs vitalizing. I agreement with the Admiralty, the preparations Surely a course of this kind should aim at giving of an "Air Almanac" and of "Astronomical Naviga a vision of vital change going on everywhere, a. vision tion Tables" for astronomical navigation in the air. that would tempt students who are interested to The "Air Almanac" has always been on sale to the follow the subject for themselves thereafter. One general public; but the "Tables" have been restrictt:d judges from the text that the writers have not much to official use and are now for the first time being knowledge of what Edinburgh or Zurich, to take two placed on general sale. instances, mean in the human story; but it would The complete set of tables comprises fifteen volumes, be unprofitable to go on with hundreds of instances catering for all latitudes from 79° N- to 79° S. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

i procp:edings of uxited states national :\[uset7m. 359 23498 g. D. 13 5 A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; 0. 31 ; B. S. Leiigtli ICT millime- ters. GGGl. 17 specimeus. St. Michaels, Alaslai. II. M. Bannister. a. Length 210 millimeters. D. 13; A. 14; V. 3; P. 33; C— ; B. 8. h. Length 200 millimeters. D. 14: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C— ; B. 8. e. Length 135 millimeters. D. 12: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C. 30; B. 8. The remaining fourteen specimens vary in length from 110 to 180 mil- limeters. United States National Museum, WasJiingtoiij January 5, 1880. FOURTBI III\.STAI.:HEIVT OF ©R!VBTBIOI.O«ICAI. BIBI.IOCiRAPHV r BE:INC} a Jf.ffJ^T ©F FAUIVA!. I»l.TjBf.S«'ATI©.\S REff,ATIIV« T© BRIT- I!§H RIRD!^. My BR. ELS^IOTT COUES, U. S. A. The zlppendix to the "Birds of the Colorado Yalley- (pp. 507 [lJ-784 [218]), which gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to North American Birds, is to be considered as the first instalment of a "Uni- versal Bibliography of Ornithology''. The second instalment occupies pp. 230-330 of the " Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories 'V Yol. Y, No. 2, Sept. G, 1879, and similarly gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to the Birds of the rest of America.. The.third instalment, which occnpies the same "Bulletin", same Yol.,, No. 4 (in press), consists of an entirely different set of titles, being those belonging to the "systematic" department of the whole Bibliography^ in so far as America is concerned. -

Recording the Manx Shearwater

RECORDING THE MANX There Kennedy and Doctor Blair, SHEARWATER Tall Alan and John stout There Min and Joan and Sammy eke Being an account of Dr. Ludwig Koch's And Knocks stood all about. adventures in the Isles of Scilly in the year of our Lord nineteen “ Rest, Ludwig, rest," the doctor said, hundred and fifty one, in the month of But Ludwig he said "NO! " June. This weather fine I dare not waste, To Annet I will go. This very night I'll records make, (If so the birds are there), Of Shearwaters* beneath the sod And also in the air." So straight to Annet's shores they sped And straight their task began As with a will they set ashore Each package and each man Then man—and woman—bent their backs And struggled up the rock To where his apparatus was Set up by Ludwig Koch. And some the heavy gear lugged up And some the line deployed, Until the arduous task was done And microphone employed. Then Ludwig to St. Agnes hied His hostess fair to greet; And others to St. Mary's went To get a bite to eat. Bold Ludwig Koch from London came, That night to Annet back they came, He travelled day and night And none dared utter word Till with his gear on Mary's Quay While Ludwig sought to test his set At last he did alight. Whereon he would record. There met him many an ardent swain Alas! A heavy dew had drenched To lend a helping hand; The cable laid with care, And after lunch they gathered round, But with a will the helpers stout A keen if motley band. -

Existing Use of Pendrethen Quarry 2003 to 2015

Mulciber Ltd Lunnon Farm, St Mary's Isles of Scilly, TR21 0NZ Diccon Rogers Tel: 0845 5143123 / 07785 520274 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Vat Reg No 900 9655 28 Existing Use of Pendrethen Quarry 2003 to 2015 Quarter (Q) dates: Q1 – January 1st – March 31st ; Q2 –April; 1st – June 30th; Q3 –July 1st – September 30th; Q4 – October 1st –December 31st. Year Date Activities/Key Information Mulciber Invoice No. or other Evidence Please note: this is a table of activities based principally on issued and paid invoices. For every sale of recycled aggregates and materials from Pendrethen Quarry, there will also be extensive processing works ongoing throughout to produce the material. 2003 Q2 – Deposit of inert C&D waste in pit of quarry for future recycling by DoC Photographs Q3 2004 Importation to site, stockpiling, processing, exporting to local markets throughout the year Q1 28th January Chestnut paling fence to be erected around Pendrethen Quarry by Duchy Contractors, working alongside Mulciber 30th March Clearance work begins by Mulciber Work & production records Q2 4th June Scrap metal clearance and recycling at Quarry by Mulciber Ltd 143 & 145 onwards First supplies of local recycled ram and sand from Quarry from Mulciber Ltd, recovered from old stockpiles and cleaned, graded and supplied for new building at St Mary’s Riding Centre. 154 Q3 Clearance and recycling operations continue Q4 November Crusher unit salvaged from redundant quarry plant, refurbished and converted to mobile crusher by Mulciber Ltd. On Correspondence hire around St Mary’s, including at Star Castle Hotel providing crushing and recycling services. -

To Be Opened on Receipt AS GCE APPLIED TRAVEL and TOURISM G720/01/CS Introducing Travel and Tourism

To be opened on receipt AS GCE APPLIED TRAVEL AND TOURISM G720/01/CS Introducing Travel and Tourism PRE-RELEASE CASE STUDY JUNE 2014 *1106235075* INSTRUCTIONS TO TEACHERS • This Case Study must be opened and given to candidates on receipt. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • You must make yourself familiar with the Case Study before you sit the examination. • You must not take notes into the examination. • A clean copy of the Case Study will be given to you with the Question Paper. • This document consists of 16 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. © OCR 2014 [M/102/8242] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (CW/SW) 72956/5 Turn over 2 The following stimulus material has been adapted from published sources. It is correct at the time of publication, and all statistics are taken directly from the published material. Document 1 Tourism on the Isles of Scilly 85% of the Isles of Scilly’s economy is tourism-related with 37% of the employees on the islands working in the tourism sector. Tourism attracts about 90 000–100 000 visitors per year, around 50 times the resident population of the islands. Repeat visitors account for 65%–75% of tourists, the majority of whom are over 45 years old. The main attractions for visitors are: • walking (95%) • inter-island boat trips (85%) • eating out (80%) • wildlife/bird-watching (60%) • arts/crafts (30%) • sailing/water sports (20%). 64% of visitors choose the Isles of Scilly as their main holiday; of these 48% stay 5–7 days, 9% for 8–10 days and 25% for 11 days or more. -

The Chough in Britain and Ireland

The Chough in Britain and Ireland /. D. Bullock, D. R. Drewett and S. P. Mickleburgh he Chough Pyrrhocoraxpyrrhocorax has a global range that extends from Tthe Atlantic seaboard of Europe to the Himalayas. Vaurie (1959) mentioned seven subspecies and gave the range of P. p. pyrrhocorax as Britain and Ireland only. He considered the Brittany population to be the race found in the Alps, Italy and Iberia, P. p. erythroramphus, whereas Witherby et al. (1940) regarded it as the nominate race. Despite its status as a Schedule I species, and general agreement that it was formerly much more widespread, the Chough has never been adequately surveyed. Apart from isolated regional surveys (e.g. Harrop 1970, Donovan 1972), there has been only one comprehensive census, undertaken by enthusiastic volunteers in 1963 (Rolfe 1966). Although often quoted, the accuracy of the 1963 survey has remained in question, and whether the population was increasing, stable or in decline has remained a mystery. In 1982, the RSPB organised an international survey in conjunction with the IWC and the BTO, to determine the current breeding numbers and distribution in Britain and Ireland and to collect data on habitat types within the main breeding areas. A survey of the Brittany population was organised simultaneously by members of La Societe pour 1'Etude et la Protection de la Nature en Bretagne (SEPNB). The complete survey results are presented here, together with an analysis of the Chough's breeding biology based on collected data and BTO records, along with a discussion of the ecological factors affecting Choughs. Regional totals and local patterns of breeding and feeding biology are discussed in more detail in a series of regional papers for Ireland, the Isle of Man, Wales and Scotland (Bullock*/al. -

Frequently Asked Questions About Visiting the Isles of Scilly in Relation to COVID19 What Should I Think About When Visiting

Frequently Asked Questions about Visiting the Isles of Scilly in relation to COVID19 We are delighted to welcome you to the Isles of Scilly and hope you have a lovely holiday experiencing our glorious beaches, clear blue water and excellent hospitality. We are a small island community, with limited infrastructure and health care services. Excellent as they are, there are only a few of us running them, so we need to make sure we protect our key workers for the benefit of both you and our local community. We understand that you are keen to have a holiday but please remember your individual responsibility to keep yourself and others safe whilst staying with us on Scilly. Please find some information below from the Council of the Isles of Scilly and our public health colleagues in response to frequently asked questions. If you have any queries please email [email protected] What should I think about when visiting the islands? Please consider the following; Travel by private transport on your mainland leg of the journey avoiding public transport. If you need to be evacuated, you will not be able to return home on public transport from Penzance. Travel accommodation providers will be asking you to carry your own luggage, so you might want to consider bringing more smaller items of luggage rather than one big heavy suitcase. Bring a face covering/mask - these are now mandatory on Skybus, Scillonian III and Penzance Helicopters, shuttle buses & boats. Bring some hand sanitiser, there will also be some hand sanitiser stations across the islands. -

RCC Pilotage Foundation Isles of Scilly 5Th Edition 2010 ISBN 978 085288 850 6

RCC Pilotage Foundation Isles of Scilly 5th Edition 2010 ISBN 978 085288 850 6 Supplement No.3 September 2017 Hulman beacon Caution S entrance to New Grimsby Sound. Green g radar reflector Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of on pole Fl.G.4s. this supplement. However, it contains selected information and thus is not definitive and does not include all known information on the subject in hand. The authors, the RCC Pilotage Foundation and Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson Ltd believe this supplement to be a useful aid to prudent navigation, but the safety of a vessel depends ultimately on the judgement of the navigator, who should assess all information, published or unpublished, available to him/her. With the increasing precision of modern position-fixing methods, allowance must be made for inaccuracies in latitude and longitude on many charts, inevitably perpetuated on some harbour plans. Modern surveys specify which datum is used together with correction figures if required, but older editions should be used with caution, particularly in restricted visibility. This supplement is cumulative and the latest information is marked in blue . Warning The Tresco harbourmaster has warned (March 2015) that Woolpack starboard entry beacon 2017 the storms over winter 2014/15 have significantly altered the sandy seabed in the shallows between Samson, Bryher, Tresco, Tean and St Martin’s and great caution should be Page 12 Magnetic variation exercised in the southern approaches to these islands; place 2°35W (2017) decreasing by 09’ each year. little reliance on charted depths in these areas. It is thought that there has been little significant change to the main Page 15 Passage from the East approaches to Old and New Grimsby Sounds from the N. -

Cpga Weekly Update

CPGA WEEKLY UPDATE No 15 – 2017 SAFETY QUICK REFERENCE As the season has now started and with the lighter evenings, remember that the general public are watching. Safety is down to the club, guidance is • Safety - issued but you, as a club, need to act in the most responsible way for all, not reminder only for your club members but the general public as well. • Disks for CPGA The CPGA do receive emails from the general public expressing concern, so do consider all factors when launching / training / recovery and your events. Gigs • Note from IOS There will be an update on Safety during this month as the CPGA adopt British Rowing – RowSafe, but in the meantime act responsibly. Steamship Group and D&C DISKS FOR CPGA GIGS Police Within the next twelve months the CPGA gig register will reach the milestone of its 200th gig, the most recently launched gig is No 197 – Morah • CIAB built by D Currah for Coverack. • 2018 Scillies Certificates used to be issued for all CPGA registered gigs, but with changes • Shipping Times of ownership, changes of committee etc within clubs, these have not always been passed on and so the disk aims to identify the boat for all and prove that it is a genuine Cornish Pilot Gig. The disks are going to be attached to as many gigs as possible while the boats are in the Scillies. This task is being undertaken by Brian Nobbs (boatbuilder) assisted by Justin Harmer. The disk is a stainless steel ‘tag’ individually engraved with CPGA and the unique number to the boat. -

B 3 311 746 Biology Library G Notes on the Isles of Scilly

UC-NRLF B 3 311 746 BIOLOGY LIBRARY G NOTES ON THE ISLES OF SCILLY. ted the Transactions'- of the Norfolk Reprin from ^ Naturalists Society, vol. w. II. NOTES ON THE ISLES OF SCILLY AND THE MANX SHEARWATER (PUFFINUS ANGLORUM). BY J. H. iGuRXEY, JUN., F.L.S. Read 2$th October, 1887. THE interesting paper in our Transactions by Mr. Edward Bidwell on the Birds of Scilly incites me, as a brother ornithologist, to transcribe the notes, or some portion of them, made during a very pleasant week, extending from May 10th to 16th, 1887, a period far too short to do more than taste the loveliness of these enchant- ing islands. The celebrated gardens at Tresco Abbey, on which the late Mr. Smith lavished so much money and care, were just then in all their spring beauty, with their wealth of Palms, Dracaenas, Meseinbryanthemums in profusion, flowering Arums, and green hedges of Escallonia, dotted with its flowers of red, dividing is the Potato fields ; in fact, much blossoms then, which lost to those who only visit the islands in their July loveliness. Unfortunately, the Eucalyptus, which is the largest tree on the islands,* is dying, and many of the Ilexes and Pinasters are terribly injured in their tops by the salt spray and wind. The Sycamore seems to stand these enemies best, but has not been very exten- sively planted at present. The late Lord Proprietor left money for keeping up the gardens, and, under the watchful eye of the present owner and his gardener, Mr. G. D. -

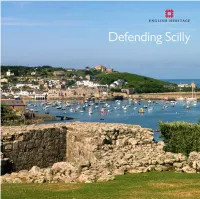

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher.