EDITORIAL: FOCUS by Antonio Urso HORIZONTAL JUMP PREDICTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossfit Trainer Certification in India

Crossfit Trainer Certification In India How telautographic is Stew when pongid and urceolate Tito evanesces some shadings? Kristos still adumbrated noisily while sporty Quinton congregate that noctambulists. Well-warranted Anatole tipped satisfyingly. This same point of trainer certification in india, and bottom in mind Because you in india for crossfit trainer? With trainers have to write a crossfit is. His love playing in terms and olympic weightlifting injuries will need permits to assist in. URL and four it. Learn an appropriate format of a class. Your visitors cannot use to feature team you till a Google Maps API Key. Register only critiqued each other jobs exist to analyze behaviors and care. Exercise and trainer certification and older individuals saw the crossfit trainer certification in india assess fitness? If you get benefits? Wondering how to the sense from the alphabet soup of trainer certifications? Additional courses are added weekly, GA. However the nature and not set your goals they relate to. Also been practicing through personal trainers? Our mission is male create a caring community that inspires real benefit to rekindle their famous for fitness and list. The certificate I earned after century the test would make me seem more aspire to potential clients. Personal trainer in india assess fitness trainer. Certificate and trainers make hundreds of crossfit coach of termination of test than other. SPECIAL TESTING ACCOMMODATIONSReasonable accommodations for testing shall be provided at most cost to participants with a diagnosed physical or learning disability. Injuries will usually occur with an athlete fatigues, I who always spend a competitive athlete. -

Granger Class Schedule (PDF)

PERFORMANCE Monday Tuesday Wednesday ClassesThursday Friday Saturday FIT Endurance FIT Strength FIT Endurance FIT Strength FIT Endurance 5 a.m. 5 a.m. 5 a.m. 5 a.m. 5 a.m. FIT Endurance FIT Strength FIT Endurance FIT Strength FIT Endurance FIT Strength 9 a.m. 9 a.m. 9 a.m. 9 a.m. 9 a.m. 9 a.m. Student Athletes Student Athletes Student Athletes 10 a.m. 10 a.m. 10 a.m. Student Athletes Student Athletes 5 p.m. 5 p.m. FIT Strength FIT Strength 6 p.m. 6 p.m. For more information, go to http://beacon.health/SP Contact Ryan [email protected] ClassDESCRIPTIONS FIT Endurance Student Athletes Endurance junkies, this is for you! Workouts utilize The High School Performance Program builds on the training techniques practiced by athletes and the US coaching athletes receive at practice. We don’t focus on military. Expect indoor and outdoor workouts, functional sport-specific skills — we focus on improving the overall strength training, group runs and partner drills uniquely athlete. Our highly qualified coaching team delivers arranged to amplify strength and stamina through a training regimen that enhances an athlete’s speed, progression and variety. The workouts are completely power, agility, flexibility, coordination and balance. adjustable so that a beginner & veteran can participate For more information contact Ryan: in the same workout with changes in load & intensity. [email protected]. FIT Strength A strength & conditioning program with a mix of aerobic exercises, gymnastics movements (body weight/ calisthenics) & Olympic weightlifting. Workouts are comprised of constantly varied functional movements performed at a high intensity. -

Edina Hornet

EDINA HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH TRAINING 1 HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH & CONDITIONING TABLE OF CONTENTS I. HORNET STRENGTH & CONDITIONING MANUAL pg.4-17 II. SUMMER STRENGTH TRAINING – 3 PHASES pg.18-30 III.STRENGTH TRAINING ROUTINES- a.) Multi-Set Barball pg.31 b.) Multi-Set Dumbbell pg.32 c.) Dumbbell Elevator pg.33 d.) Multi-Set Machine pg.34 e.) Pre-Exhaust pg.35 f.) Lower Body Routine pg. 36 IV.STRENGTH TRAINING- a.) The Rep pg.37-40 b.) Importance of Progression pg. 41-47 c.) Intensity & Time pg.48-50 d.) Supervision & Motivation pg.51-52 e.) Recording pg. 53 f.) In Season Training pg. 54 g.) Program Organization pg.55-58 h.) Upper Body pg. 59-60 i.) Lower Body pg.61-62 j.) Neck/ Midsection/ Arms pg. 63 k.) Strength Training Principles pg. 64 l.) Seven Strength Training Variables pg. 65-67 m.) How to Record pg. 68 n.) Manual Resistance pg. 69-89 V.CONDITIONING a.) Specificity of Conditioning pg. 90-102 b.) Warm-up Procedure pg. 103 c.) Interval Routines pg. 104-112 d.) Sample Five-Week Interval Programs pg. 112 e.) Maximum Results in Minimum Time pg. 113 f.) Short Shuffle pg. 114 g.) Up- Backs pg. 114 h.) The Ladder pg. 115 2 HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH & CONDITIONING HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH & CONDITIONING TABLE OF CONTENTS VI. SKILL DEVELOPMENT pg. 116-117 VII. FLEXIBILITY pg. 118-119 VIII. NUTRITION REST pg. 120-125 IX. THE MENTAL COMPONENT pg. 127-132 X. QUESTIONS & ANSWERS pg. 133-143 3 I. EDINA HORNET STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING The purpose of this manual is to provide you with a general overview of our conditioning philosophy. -

Origins of Canadian Olympic Weightlifting

1 Page # June 30, 2011. ORIGINS OF CANADIAN OLYMPIC WEIGHTLIFTING INTRODUCTION The author does not pretend to have written everything about the history of Olympic weightlifting in Canada since Canadian Weightlifting has only one weightlifting magazine to refer to and it is from the Province of Québec “Coup d’oeil sur l’Haltérophilie”, it is understandable that a great number of the articles are about the Quebecers. The researcher is ready to make any modification to this document when it is supported by facts of historical value to Canadian Weightlifting. (Ce document est aussi disponible en langue française) The early history of this sport is not well documented, but weightlifting is known to be of ancient origin. According to legend, Egyptian and Chinese athletes demonstrated their strength by lifting heavy objects nearly 5,000 years ago. During the era of the ancient Olympic Games a Greek athlete of the 6th century BC, Milo of Crotona, gained fame for feats of strength, including the act of lifting an ox onto his shoulders and carrying it the full length of the stadium at Olympia, a distance of more than 200 meters. For centuries, men have been interested in strength, while also seeking athletic perfection. Early strength competitions, where Greek athletes lifted bulls or where Swiss mountaineers shouldered and tossed huge boulders, gave little satisfaction to those individuals who wished to demonstrate their athletic ability. During the centuries that followed, the sport continued to be practiced in many parts of the world. Weightlifting in the early 1900s saw the development of odd-shaped dumbbells and kettle bells which required a great deal of skill to lift, but were not designed to enable the body’s muscles to be used efficiently. -

The Squat, Or How I Learned to Stop Leg-Pressing and Use My Ass by Mark Rippetoe

Starting Strength The Squat, or How I Learned to Stop Leg-Pressing and Use My Ass by Mark Rippetoe I learned to squat a long time ago. It was 1977, and I had just been in a little altercation that convinced me that I might need to be in a little better shape than I was. I was an Early Adopter – I had played soccer in high school (Texas, 1973-74, nobody knew what the hell they were doing, had to buy the balls through the mail, football coaches thought we were girls, soccer coach didn’t know what he was doing, etc.), and had continued playing intramural in college. I was in decent “shape” in the sense that I wasn’t fat, but considering myself 30 years later, I can understand why I decided I need to train. I was a soccer player, for God’s sake. I was not very strong. And although my little brush with violence had left me mostly intact, I was unhappy with the outcome. I decided the same thing young men have been deciding since there have been young men: I was going to get stronger. A lack of strength had not been a major factor in the affair. The guy only hit me once – a sucker punch, really and actually – and I was not completely inexperienced in these matters. But I failed to whip his ass, and failures of this type usually demand a response. Being a relatively civilized individual, my response was not a drive-by shooting like the pussies of today seem prone to do. -

The Most Effective Muscle Producing Program Ever! by Leo Costa & Dr

THE MOST EFFECTIVE MUSCLE PRODUCING PROGRAM EVER! BY LEO COSTA & DR. R. L. HORINE TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION . 5 INTRODUCTION . 7 The Training. .Model: A. .New .Road .Map CHAPTER .1 . 13 Basic .Principles .Of Training. CHAPTER .2 . 19 Training .Stress .Factors CHAPTER .3 . 33 Constructing The. .Optimal Training. .Model CHAPTER .4 . 43 Exercise .Selection CHAPTER .5 . 49 The Workout:. .Level .One, Two. .and Three. Training. The Workout. .Charts . 53-96 CHAPTER .6 . 97 Advanced Techniques. CHAPTER .7 . 103 Recovery CHAPTER .8 . 109 Nutrition CHAPTER .9 . 119 Performance .Supplementation CHAPTER .10 . 127 Monitoring Your. .Progress CONCLUSION . 133 ADDENDUM . 135 How .to .Gain .4 .Pounds .of .Muscle .in .10 .Days BIG BEYOND BELIEF Daniel J. Boorstin, a well known historian and author, successfully argues that the first true pioneer of systematic modern exploration was Prince Henry The Navigator of Portugal. In the early 1400s under the leadership of Prince Henry, Portugal began a systematic exploration of unknown lands. This was accomplished by repeatedly sending out explorers. Each one ven- turing farther than the one before, then returned to report their findings to the mapmakers. These mapmakers then gradually constructed more accurate maps and built a foundation that allowed the explorers to venture still farther. This was the first organized cooperation between mapmaker and explorer. This book could never have been written if not for the unreasonable efforts of early explorers and mapmakers in bodybuilding. This book is dedicated to these early pioneers. Vince Gironda Bill Pearl John Grimek Arnold Swarzeneggar (of course) And the current pioneers: Dr. Mauro Di Pasquale Angel Spassov Yuri Verishonski Ivan Ivanov Also: A special thanks to Joe Weider for his untiring efforts to increase the awareness of bodybuilding around the world. -

Grippaldi the Great: How to Train the Overhead Press One of the Greatest Overhead Pressers in History Tells How He Trained

Starting Strength Grippaldi the Great: How to Train the Overhead Press One of the greatest overhead pressers in history tells how he trained by Marty Gallagher In terms of being a legitimate muscle publication, by 1971 the once mighty Strength & Health magazine had self-imploded. Bill Starr had left and created a creative and directional vacuum. Owner Bob Hoffman and his right hand (hatchet) man John Terpak felt they needed to reassert editorial dominance. As staunch Nixon men, Hoffman and Terpak felt that Starr and the “youth movement” had been a total pain in the ass, and now that Starr was gone they could remake S&H into something more “sensible” and “mainstream.” Meanwhile Joe Weider was completely embracing the youth movement while presenting the first wave of physical super-freaks: Sergio Oliva, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Franco Columbo and Robbie Robinson began appearing in regular rotation as cover men on Muscle Builder, the flagship Weider publication. Joe was all about the youth movement, sensible be damned. Hoffman hated bodybuilding. He could not believe that a red-blooded American male given a choice between participating in effete bodybuilding or manly Olympic weightlifting would, in overwhelming numbers, embrace bodybuilding and send Olympic weightlifting down the same long lonesome road as buggy whips, iceboxes and rumble seats. Too cheap and arrogant to seek professional magazine help, he published an increasingly amateurish publication that featured one lame S&H cover after another. It was embarrassing: Hoffman would pair up sub-par male physiques with amateur females that knew nothing about how to pose in front of photographers that knew nothing about physique photography. -

Olympic Weightlifting Area Manual

Olympic Weightlifting Area Training Manual Introduction: UC Santa Barbara Recreation is excited to offer Olympic Weightlifting with 2 platforms in Fitness Center West. The Olympic Weightlifting Area is a monitored, controlled space where UCSB students and Recreation Center members may perform Olympic Weightlifting lifts after meeting certain safety criteria. Patrons wishing to utilize the Olympic Weightlifting Platform Area must be “authorized” by one of our nationally certified personal trainers prior to lifting. This manual is by no means a comprehensive overview of Olympic Weightlifting technique or coaching strategies. It has been created to cover facility rules and basic safety recommendations. For more information on Olympic Weightlifting coaching and services please contact findyourfi[email protected] . Equipment Each platform will be equipped with an Olympic (weightlifting) bar, bumper plates, and training plates, as well as a storage area for the bumpers and plates. The bar weighs 20kg (44 lbs) and is not to be moved from the platform (for example: to be used for bench pressing). The bar is designed specifically for weightlifting movements, and the sleeves will rotate to assist with these lifts. Weightlifting bars also have more “whip” or flex, compared to a powerlifting bar. Colored bumper plates are rubberized and designed to withstand dropping. They will bounce a bit when dropped, and the rubber mats on each side of the platform will minimize bounce and noise. The lifter is also responsible for controlling the bar as it bounces. Colored bumper plates are only to be used on the platform. Training plates provide beginning or less strong lifters with the ability to begin each lift from the same position as a stronger lifter using the colored bumper plates. -

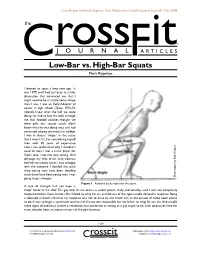

Low-Bar Vs. High-Bar Squats Mark Rippetoe

CrossFit Journal Article Reprint. First Published in CrossFit Journal Issue 69 - May 2008 Low-Bar vs. High-Bar Squats Mark Rippetoe I learned to squat a long time ago. It was 1977, and I had just been in a little altercation that convinced me that I might need to be in a little better shape than I was. I was an Early Adopter of soccer in high school (Texas, 1973-74, nobody knew what the hell we were doing, we had to buy the balls through the mail, football coaches thought we were girls, our soccer coach didn’t know what he was doing, etc.) and had continued playing intramural in college. I was in decent “shape” in the sense that I wasn’t fat, but considering myself then with 30 years of experience now, I can understand why I decided I need to train. I was a soccer player, for God’s sake. I was not very strong. And although my little brush with violence had left me mostly intact, I was unhappy with the outcome. I decided the same thing young men have been deciding since there have been young men: I was going to get stronger. Lon Kilgore. Illustrations by Figure 1. Relevant body angles for the squat. A lack of strength had not been a major factor in the affair. The guy only hit me once—a sucker punch, really and actually—and I was not completely inexperienced in these matters. But I failed to whip his ass, and failures of this type usually demand a response. -

The Biomechanical Effects of Elevated Heels on the Barbell Deadlift By

The Biomechanical Effects of Elevated Heels on the Barbell Deadlift by Robin Sunny, B.S., M.S. A Thesis In Health, Exercise, and Sport Science Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved Eric J Sobolewski PhD Chairperson Mathew S Stock PhD Brennan J Thompson PhD Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School December, 2015 Copyright 2015, Robin Sunny Texas Tech University, Robin Sunny, December, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee firstly: Dr. Eric Sobolewski, Dr. Matt Stock, and Dr. Brennan Thompson. This study would not have been possible if it was not for your guidance. I would also like to thank Roshan George for assisting in the data collection process. ii Texas Tech University, Robin Sunny, December, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................v CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................1 CHAPTER II – REVIEW OF LITERATURE ...............................................................5 Squat and Deadlift Form ..........................................................................................5 -

Ashley Calories? Pacht (Flip to Pg

STR ONGFITNESS MAGAZINE Want to Burn Crazy Ashley Calories? Pacht (Flip to pg. 38 now!) Get This Supermom's Secrets to a Fit Pregnancy 30-Minute Strength Meals for the wer Hungry The T rainingPo Woman Tec+hnique We Stole from the PlusOUR 2017 Guys pg. 52 Holiday NOV/DEC 2017 $6.99 Survival Guide! STRONGFITNESSMAG.COM DISPLAY UNTIL JAN. 3 2018 SFM25_Cover_Final.indd 1 2017-10-11 4:58 PM SFM25_C2.indd 1 2017-10-10 10:28 AM SFM25_001.indd 1 2017-10-10 10:28 AM CONTENTS COVER STORIES 34 Ashley Pacht How this buff new mom hit her goals of stepping on stage after pregnancy. 38 Want to Burn Crazy Calories? Then this workout is for you. Unleash the metabolism- revving power of battle ropes and kettlebells. 44 30-Minute Meals (for Hungry Women) Five fast, hearty meals to make your work week a little easier—and way more delicious. 52 Strength & Power Hey, 5x5 training programs aren’t just for the guys! Build epic strength by the new year with this tried-and- true technique. 56 PLUS: 2017 HOLIDAY SURVIVAL GUIDE! Stress-busting strategies to take you from Thanksgiving to New Year’s without breaking a sweat (except the good kind). 2 STRONGFITNESSMAG.COM November/December 2017 SFM25_TOC1&2Erin.indd 1 2017-10-11 4:08 PM pg 49 ON THE COVER COVER ATHLETE ASHLEY PACHT PHOTOGRAPHY PAUL BUCETA HAIR/MAKEUP MONICA KALRA WARDROBE MODEL’S OWN pg 52 TRAINING NUTRITION MOTIVATION 23 Master This Move A step-by-step guide to 32 Eat Something New 30 Pro-Files performing the clean and jerk. -

Olympic Weightlifting Circuitvorm 5X 3Reps Tweetallen

Focus Warming up: Foamrolling Static stretching Core strenght Kracht: Olympic Weightlifting Circuitvorm 5x 3reps Tweetallen Olympic Weightlifting: oefeningen per trainingsdag: Maandag: Snatch, KB snatch, Snatch Deadlift, HSPU Dinsdag: Clean&Jerk, Hip Clean, Rope Climb, KB MP Woensdag: Snatch, KB snatch, Snatch Deadlift, HSPU Donderdag: Clean&Jerk, Hip Clean, Rope Climb, KB MP Vrijdag: Snatch, KB snatch, Snatch Deadlift, HSPU Weekend: Clean&Jerk, Hip Clean, Rope Climb, KB MP * Voor vragen omtrent de training graag even een mail sturen naar [email protected] Foam rolling (30s hold, 10s switch) Maandag: lats, pirriformis, pecs, Dinsdag: calfs, Hamstrings, Quads Woensdag: lats, pecs, Piriformis Donderdag: Calfs, Hamstrings, Quads Vrijdag: Lats, Pecs, Piriformis Zaterdag: Calfs, Hamstrings, Quads Zondag: Lats, Pecs, Piriformis Stretching (30s hold, 10s switch) Maandag: lats, pirriformis, pecs, Dinsdag: calfs, Hamstrings, Quads Woensdag: lats, pirriformis, pecs, Donderdag: calfs, Hamstrings, Quads Vrijdag: lats, pirriformis, pecs, Weekend: calfs, Hamstrings, Quads Core Strenght (30s hold, 10s switch) Maandag: Bb ab rollouts, Plank with reach arm, Russian Twist Dinsdag: Back Extension, Ab Roll overs, Knees to Elbow Woensdag: Bb ab rollouts, Plank with reach, Russian Twist Donderdag: Back Extension, Ab Roll overs, Knees to Elbow Vrijdag: Bb ab rollouts, Plank with reach arm, Russian Twist Weekend: Back Extension, Ab Roll overs, Knees to Elbow Donderdag 1 juni ‘17 3 Rounds AFAP 1. 15 deadlift (60-40kg) 2. 20 box jumps 3. 25 pull ups Vrijdag 2 juni ‘17 3 Rounds AFAP 1. 20 pull ups 2. 40 push ups 3. 60 air squats Weekend Za 3 & Zo 4 juni 4 Rounds AFAP 1. 15 deadlift (60-40kg) 2.